The Venezuela-China relationship, explained

In 2001, Venezuela became the first Hispanic country to enter into a "strategic development partnership" with China, a relationship that was elevated to "comprehensive strategic partnership" in 2014, and which now totals at least 790 investment projects in Venezuelan territory. That was just the beginning.

This is the first of a four-part series, which will be published on Mondays this month, that spotlights the Venezuela-China relationship.

Part One: China’s choice to penetrate the Latin American market

Part Two: China, Venezuela, and the New Silk Road in between

Part Three: The geopolitics of the dragon in Little Venice

Part Four: China, a long-term partner for Venezuela?

Key points:

- In 2001, Venezuela became the first Hispanic country to enter into a “strategic development partnership” with China, a relationship that was elevated to “comprehensive strategic partnership” in 2014, and which now totals at least 790 investment projects in Venezuelan territory. They range from infrastructure, oil, and mining to light industry and assembly.

- China’s development projects in Venezuela have disappeared over the past 11 years, mostly devoured by corruption or by the debt default that the South American country has incurred with the Asian giant, which froze many direct investments.

- Loans from China to Venezuela reached at least $50 billion by 2017, with some estimating the number to have been as high as $60 billion. (The uncertainty regarding the figure is the result of opaque loans, split into payments of $2 billion and $5 billion each.)

- As of 2016, China has stopped issuing new loans to Venezuela. Since then, Chinese representatives have sought unofficial meetings with individual members of the opposition, trying to secure guarantees that the debt, about $20 billion, will eventually be paid back.

- In 2000, there was an immigrant population of approximately 60,000 Chinese in Venezuela. Eighteen years later, President Nicolás Maduro estimates there are 500,000 Chinese citizens residing in the country.

- Venezuela has gold reserves with a commercial value of more than $200 billion. In Coltan, reserves are valued at at least $100 billion, and iron is estimated at more than $180 billion. China worked with Venezuela on the Venezuelan Mining Map in an area of 111,800 square kilometers (12.2% of Venezuelan territory), and currently has direct investments of over $580 million.

PART ONE

China’s choice to penetrate the Latin American market

The facts, beyond politics

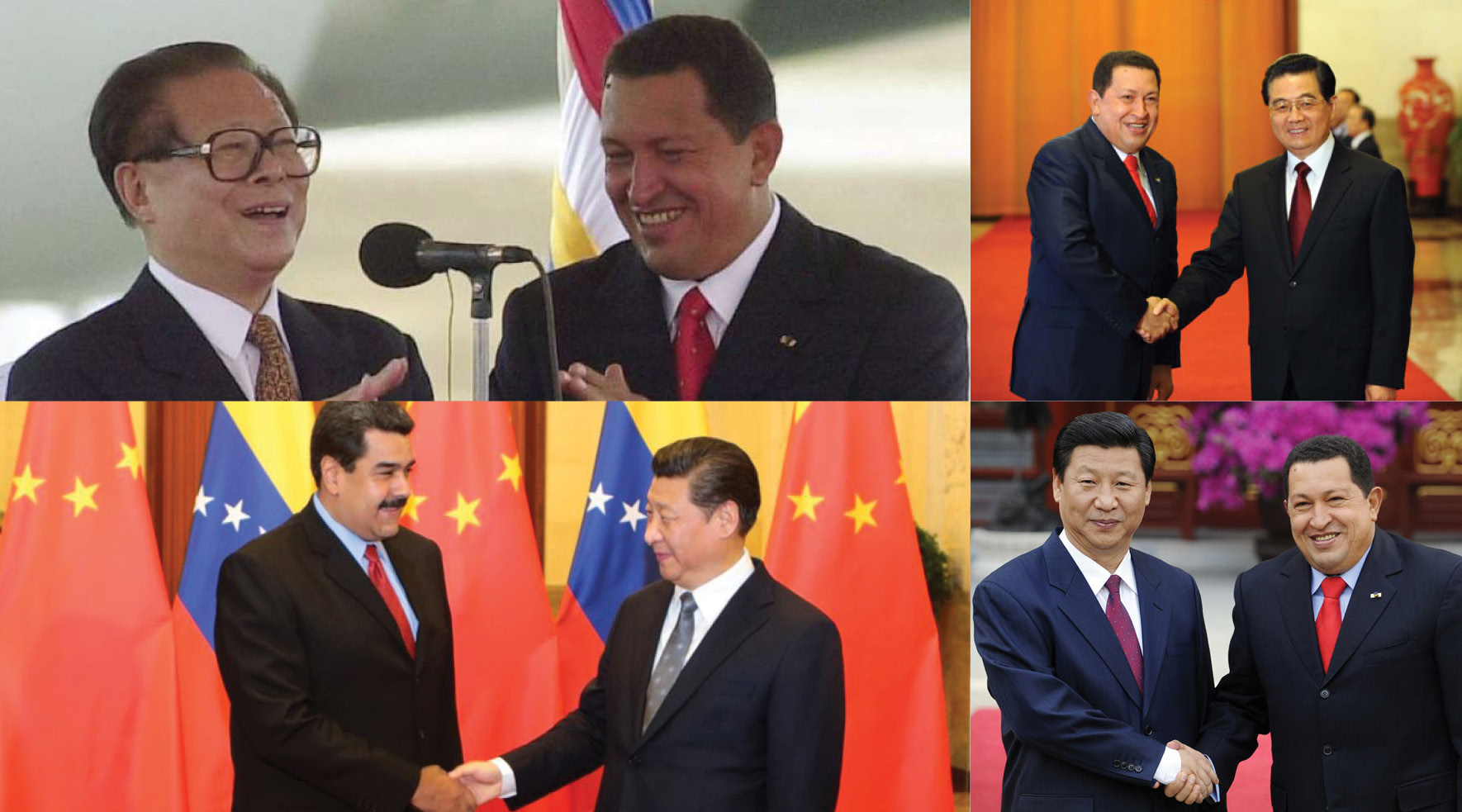

On April 18, 2001, Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez sang with Spanish pop star Julio Iglesias fragments of the song “Solamente una vez” in the Miraflores (presidential palace) in Caracas. In the audience was Jiang Zemin 江泽民, then-president of the People’s Republic of China, who attended the signing of cooperation agreements, credits, and treaties that sealed the beginning of a trade relationship between China and the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela.

Thus began a relationship of 17 years that continues with the current Venezuelan president, Nicolás Maduro.

As of December 2018, this alliance has resulted in more than 790 projects and loans of more than $50 billion, of which Venezuela has paid $30 billion in oil and other strategic materials, and currently owes at least $20 billion, which China continues to charge in gold, oil, and other materials.

Eight bilateral cooperation agreements in energy, cultural, technological, and mining matters were signed in the first stage of the alliance (2001), including a line of credit of $20 million that the Venezuelan government earmarked for the agricultural sector.

Orimulsion

The bilateral relationship has come a long way, and it all started with oil.

In 1996, Venezuela’s trade with Asia-Pacific countries was barely worth $1.2 billion, with Japan being the main partner, with a bilateral trade estimated at $700 million.

In 1997, prior to the triumph of Hugo Chávez, the National Petroleum Corporation of China made two important tenders in the third round of its “oil opening,” initiated by the government of Rafael Caldera, the last president of the so-called “Fourth Republic” period. This policy was strongly criticized by followers of Chávez — then just a presidential candidate — who denounced the delivery of Venezuelan natural resources to “imperialist powers.”

These agreements with the state oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela (Pdvsa), totaled $358 million, and constituted China’s first step in an energy relationship with Venezuela.

A crucial player was Orimulsion, a registered patent for the production of fossil fuels for industrial use, developed by oil companies affiliated with state-owned PDVSA, including British Petroleum. It consists of the transformation of extra-heavy oil, abundant in Venezuela, into a widely used energy emulsion. Its name is the combination of the region of Venezuela from where the hydrocarbon is extracted (Orinoco oil belt) and the technical name of the product: emulsion. It is an emblematic project that characterizes the commercial association between China and Venezuela.

The fuel began to be commercialized in 1988, with the first international shipment used in a Chubu Electric power plant in Japan. The model represented one of the most significant inventions of the 20th century, based on selling extra-heavy oil at the price of coal.

After signing agreements with China in 1997, Venezuela began to build a module with the capacity to produce 100,000 barrels per day of Orimulsion at a cost of $320 million. Chávez, upon winning the presidency in 1999, kept his country’s deals with China intact, and even expanded certain agreements.

In 2007, the Venezuelan Minister of Energy and Petroleum, Rafael Ramírez, announced that PDVSA was ending production of Orimulsion, arguing that its processing was not “an appropriate use for Venezuelan extra-heavy crudes,” and granted the Orimulsion patent to Chinese oil companies, which currently produces fuel for various industrial uses.

Into the 21st century

The year 2004 represented a commercial milestone for the relationship. China and Venezuela established an agreement that allowed both countries to make investments without having to pay taxes to the treasury of the other country. China has remained exempt from paying taxes on its investments made on Venezuelan territory, and vice versa.

The agreement to eliminate double taxation, something uncommon in trade agreements between nations, and that Venezuela had not previously established with its traditional partner, the U.S., is summarized in Article 24 of that agreement: “When a Chinese resident earns income in Venezuela that is subject to the provisions of the imposition of this agreement, that person must pay Chinese taxes. However, the amount can not exceed the amount of Chinese tax determined in accordance with the laws and tax regulations of China.”

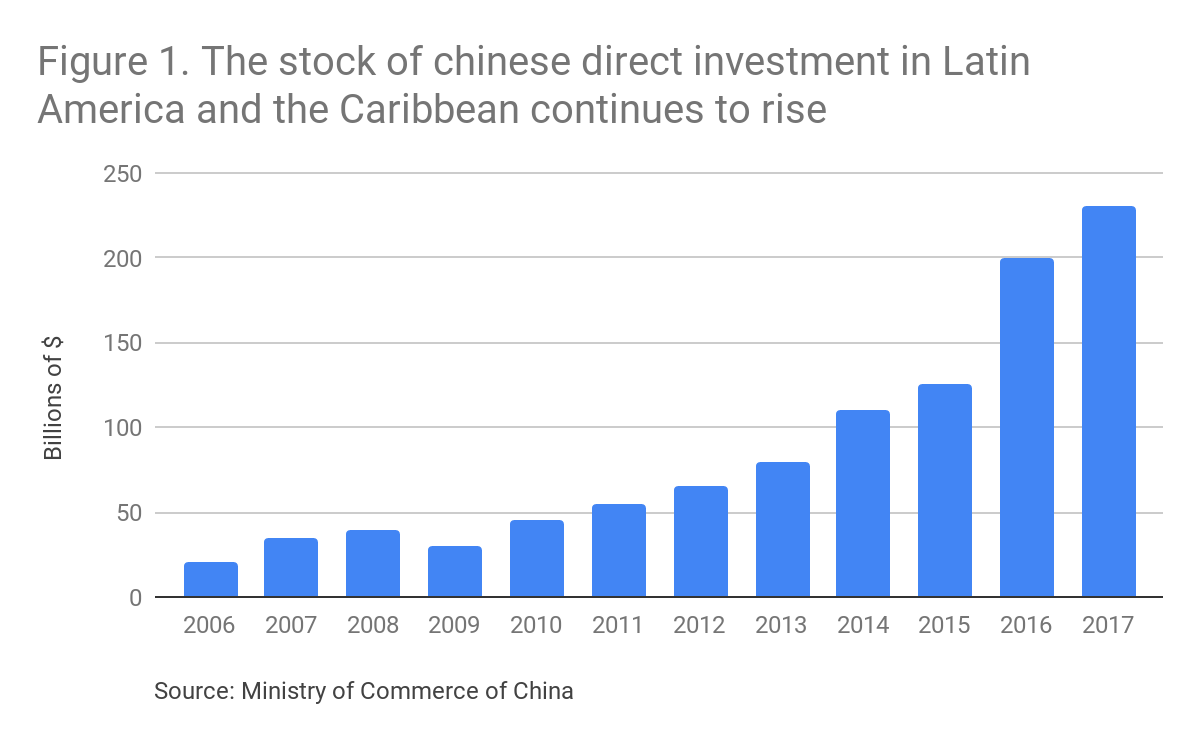

By 2005, Venezuela was the destination of more than $1 billion in direct investment from China, more than any other Latin American country. At that time, there were more than 20 companies from China operating in the areas of oil, railroad construction, mining, infrastructure, telecommunications, agriculture, production of household appliances, and trade, among others.

Then, political-economic changes in Venezuela extended to its international relationships on the continent. On April 24, 2005, President Hugo Chávez announced the suspension of Venezuela’s historic and traditional military cooperation with the United States. The U.S. had to withdraw its permanent military office from the facilities of the most important fort in Venezuela, Fuerte Tiuna, located in southern Caracas. Since 2005, joint military exercises between the U.S. and Venezuela have disappeared. Venezuela was looking for new partners, even in the area of military defense.

During the first years of Hugo Chávez’s rule, purchases of Chinese goods increased. But it was not until 2007, after the creation of the China-Venezuela Joint Fund, that purchases intensified and topped $4 billion. Thus, a relationship that was more than commercial was born.

But Venezuela has gotten poor during Chávez’s rule: Today, 94 percent of households have “insufficient income,” according to a Living Conditions Survey conducted last year. Despite its multibillion-dollar relationship with China, it’s apparent that the people have not actually benefited.

Purchases, loans, and infrastructure vs. productive investments

One of the most important external debts in Latin American history was born in 2007. The China-Venezuelan Joint Fund, created that year by Chávez, allowed Venezuela to receive loans from China in tranches of up to $5 billion, and pay them with shipments of crude oil. So far, only the Development Bank of China (CDB), a state lender, has granted credit to the Venezuelan government in the last decade under this mechanism ($37 billion).

But China has not revealed any exact figures, or for which projects the credit is granted, nor the conditions of granting. In addition, these negotiations have led to corruption by officials of the Venezuelan government, with dozen charged in Venezuela, Europe, and the U.S.

In spite of this, China has increased its investments, and currently invests more in Venezuela, via credits, than in any other Latin American country.

In October 2007, one of the first projects funded by the Joint Fund was announced. That year, Chávez created the Venezolana de Telecomunicaciones Company (Vtelca), a factory for assembly and commercialization of cell phones and other technological products in Paraguaná in the western state of Falcon.

The company was formally opened in 2009, and a couple of years later its president, Akram Makarem, announced that its workers would receive training in China to “start manufacturing the components of cell phones and the electronic circuit” and be able to design their own models. The agreement included alliances with Chinese companies such as Inspur Group and ZTE Limited.

In 2016, the then-president of the state telecommunications company Movilnet, Jackeline Farías, said that Vtelca had commercialized more than 120,000 “vergatario” model phones, a model supported by Chávez. He said the company was “at full production” and that it had been able to show its potential during the MNOAL Summit. He also promised to strengthen the GSM network to improve the scope of services in the South American country, something that was achieved to a large extent.

The company’s promise was to produce half a million mobile phones in its facilities during 2018, mostly smart, as part of an agreement signed at the 15th meeting of the Joint Commission of High Level of China and Venezuela, signed between Vtelca and ZTE. According to Vtelca, the company has historically produced more than 7.8 million cell phones in eight models of different ranges.

In addition to Vtelca, the electronic industry “Orinoquia” was born. Inaugurated in 2010 with the purpose of manufacturing communications equipment, this company was constituted with 65% of the shares owned by the Venezuelan state, through its telecom company, and 35% of the shares held by the Chinese partner Huawei Technologies.

In 2008, the projects financed by the Joint Fund included installation of a “Technology Park” branch of Huawei in Venezuela and plans to build two drug production plants. The plants never went into operation.

Although the agreements have not led to a real expansion of Venezuela’s industrial park, China’s exports to Venezuela have grown. In 1998, the year before Chávez came to power, 0.18% of Venezuela’s imports were Chinese products, while 14 years later that number had grown to 34.9%.

Other projects financed by the Joint Fund included the construction and expansion of the metro lines in the cities of Valencia and Maracaibo, the construction of urban complexes through the Great Housing Mission Venezuela, the flagship social program of the Bolivarian Revolution, as well as renovations of roads and the expansion of the nationwide land transport system. For the Chinese, the Joint Fund can be considered a success because it was able to establish assembly companies in Venezuela, namely Yutong (which manufactures buses) and Chery (a state-owned automobile company).

In addition, Venezuela has satellites in orbit thanks to its cooperation with China. The Simon Bolivar satellite for communications was launched on October 29, 2008, administered by the Ministry for Science and Technology through the Bolivarian Agency for Space Activities (ABAE) from Venezuela.

This first satellite was part of the VENESAT project, which initially was to be done with Russia, before China ultimately accepted the proposal.

Five years later, in 2013, Venezuela took control of the Miranda satellite (VRSS-1) that had been put into orbit on September 28, 2012 from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in China. The objective of this satellite is to capture high-resolution digital images of Venezuelan territory, as well as being the first remote observation satellite in the country.

Then, in 2017, Venezuela successfully launched its third satellite, the Antonio José de Sucre (known as VRSS-2), from China, which entered orbit on October 9. Designed with input from Venezuelans, it’s similar to the Miranda satellite, but incorporates two high-resolution cameras that capture images in much sharper detail, as well as an infrared camera.

In July 2009, Venezuela and China had signed an agreement for $7.5 billion to build a railway line. The government of Hugo Chávez assured that the agreement would also allow the installation in Venezuela of the first rail construction company in Latin America “with Venezuelan iron and Chinese technology.” He also promised that factories for wagons, sleepers, change-tracks, and equipment for the welding of rails would be put into operation, all of them with technological support from China, with a technology transfer under the modality of mixed companies, in which Venezuela would have 60% of the shares and China 40%.

The agreement was signed by the president of the Autonomous Institute of Railways of Venezuela, Franklin Pérez, and the vice president of the Chinese consortium, China Railway Engineering Corporation, Bai Zhongren.

Things soured in 2015 when the China Railway Group Ltd, the biggest train manufacturer in the world, quietly left a bullet train project that was part of a $7.5 billion agreement. (The contract breach came from the Venezuela side; we’ll expand on the effects of corruption in a later column.) The Chinese managers left behind $400 million in debt and unfinished infrastructure that 800 workers had toiled on for four years. It was plundered by locals in Zaraza in central Venezuela.

Similar stories can be found in several parts of Venezuela, giant projects and industrial complexes that were never finished. In Miranda, a state located in central Venezuela, specifically in Valles del Tuy, dozens of constructions with Chinese emblems and characters have been abandoned.

Yet despite this, the relationship between China and Venezuela is flourishing. For China, Latin America is a strategic objective. China’s foreign minister, Wang Yi, said last January at a continental meeting in Chile that the countries of the region “are part of the natural extension of the maritime silk route and are indispensable participants in the international cooperation of the Strip and Route project.” In the next installment, we will explain this project in more detail.

Part Two: China, Venezuela, and the New Silk Road between

Part Three: The geopolitics of the dragon in Little Venice

Part Four: China, a long-term partner for Venezuela?