The lifetime of a meme: The lesson of Zhang Jinlai, a.k.a. Liuxiaolingtong

The lifetime of a meme: The lesson of Zhang Jinlai, a.k.a. Liuxiaolingtong

The internet’s meme economy is complicated. Some memes are self-explanatory and inherently funny, but some can be overwhelming and hard to comprehend for those who weren’t online to witness them firsthand.

Take, for example, Liuxue 六学, short for Liuxiaolingtong studies 六小龄童学, a category of memes based on actor Zhang Jinlai 章金莱, better known as Liuxiaolingtong 六小龄童, which exploded on the Chinese internet at the beginning of 2019.

What in the world is Liuxue and Liuxiaolingtong?

He Keyi, writing on the WeChat platform Meirirenwu 每日人物, makes a valiant attempt to explain in a recent article called “Liuxiaolingtong: The 73rd transformation has failed.” (Yes, yes, we’ll explain this headline, too.)

The name Liuxiaolingtong originates from Zhang’s father, Zhang Zongyi 章宗义, a monkey-imitating artist who dedicated his entire acting career to perfecting his performance as a monkey. The senior started learning this kind of acting at the age of six, which explains the origin of his stage name The Sixth Kid (六龄童 Liù Líng Tóng). Naturally, Zhang Jinlai, the junior, inherited his father’s legacy and became a monkey-man. Zhang Jinlai paid homage to his father by carrying on the stage name but added the character Xiǎo 小, which means “little” (or “junior”), in his name.

The sensation of Liuxue started when a cohort of trolls poked fun at Zhang’s years-long attempt to increase his relevance after starring as Sun Wukong 孙悟空, a.k.a. the Monkey King, in a 1986 television adaption of Journey to the West (西游记 Xīyóujì). The role is widely regarded as the pinnacle of Zhang’s acting career. Seeing generally tepid reception to his subsequent works, Zhang morphed into an objectively annoying celebrity who perennially dwells on his best-received performance, constantly boasting about his legacy and attaching his entire worth on the original novel and its variations, a cultural heritage to which Zhang only made a relatively small contribution.

But unlike other sellout artists, Zhang went so far that people are now questioning his sanity. It’s documented that, at certain speaking engagements, he branded himself as the only person alive who can offer definitive interpretations of the original Journey to the West. At the funeral of Yang Jie 杨洁, director of the 1986 TV adaption, Zhang filmed a video promoting an upcoming movie where he plays the character again. In several interviews, he has basically roasted all other visual adaptions of the book for not paying enough respect to the classic, repeatedly saying, “Parodies should not be nonsense, adaptations should not be groundless recreations” (戏说不是胡说,改编不是乱编 xìshuō búshì húshuō, gǎibiān búshì luànbiān). He has advocated for laws banning parodies of classics. Toward the end of 2018, the long-simmering backlash against Zhang reached its peak after news broke that Zhang’s portrait was placed inside the home museum of Wu Cheng’en 吴承恩, author of Journey to the West. Although staffers at the museum later clarified that they came up with the idea as a way of attracting visitors, the tide against Zhang was too strong at this point.

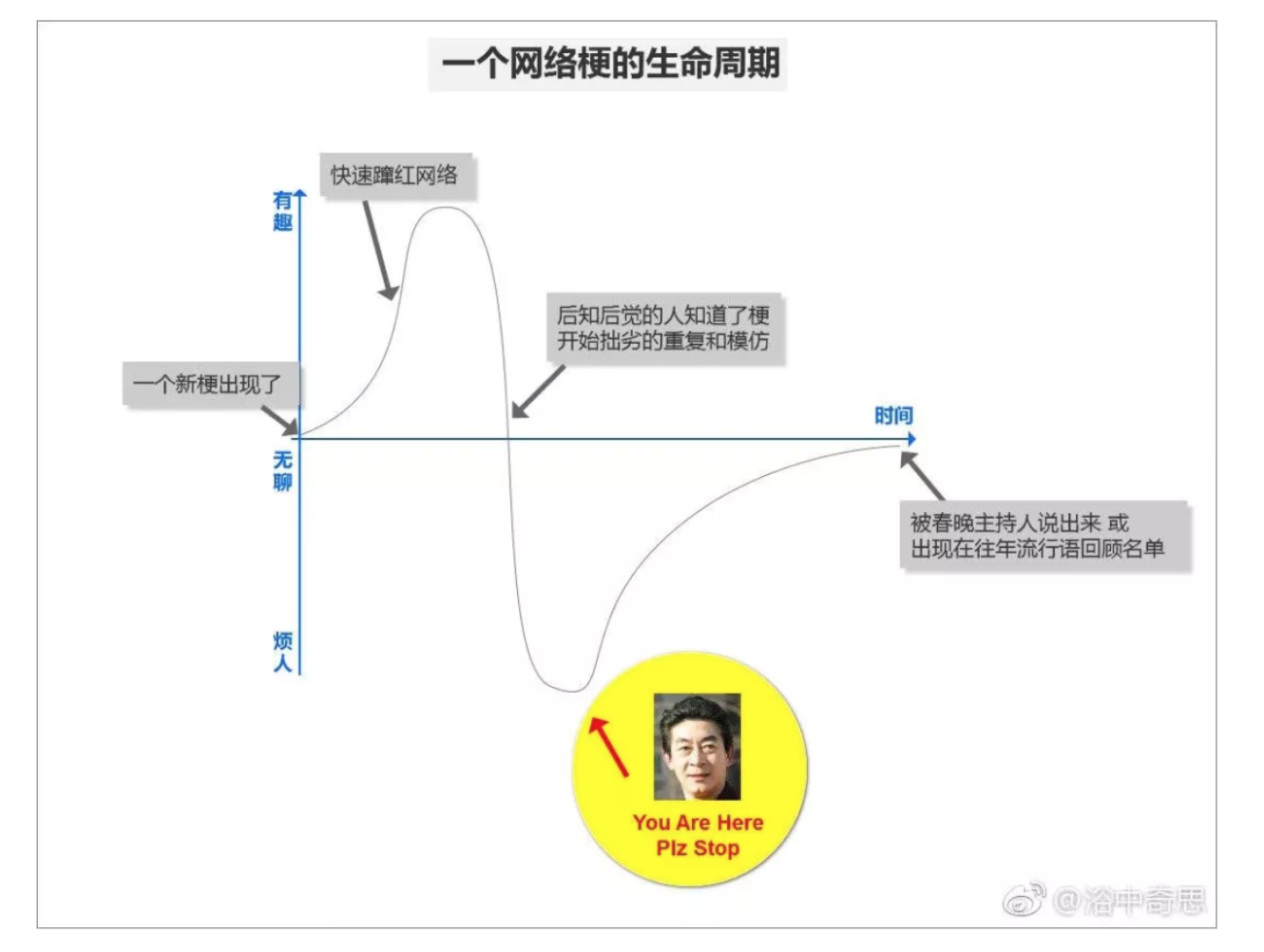

Borrowing heavily from these materials, Liuxue, which refers to a compilation of self-aggrandizing statements made by Zhang, dominated the Chinese internet in the first week of 2019. In response, Zhang said in an interview that he challenges those meme creators to reveal their identities and have a face-to-face conversation with him. He called them as “an ill-spirited group of people” who slander him.

Zhang is partially right. Liuxue was initially a smear campaign by trolls who gleefully dug up dirt on him. But as it evolved, a portion of the people who produced or enjoyed jokes about Zhang were not necessarily his haters. That’s one of the prices of being a celebrity: you will become a meme. Zhang’s aggressiveness and refusal to embrace the memes did nothing but fuel the backlash. As blogger Wu’erbang 吴二棒 points out, “The more he says, the more stuff people can work on.”

What Zhang got fundamentally wrong is the current state of internet culture, where ridicule doesn’t necessarily equate to hatred. Quite the opposite, in fact. For celebrities, especially those on the downhill of their careers like Zhang, memes about them are proof of their staying power and ability to inspire conversation — the goal of anyone in the creative industry. The author of the article “The 73rd transformation has failed” understands this — the headline is a reference to the Monkey King in Journey to the West, who is capable of 72 transformations into various animals and objects.

When exploited the right way, memes can even end up salvaging a celebrity’s dwindling cultural relevance. One example that Zhang can take some lessons from is Tang Guoqiang 唐国强, a 67-year-old actor best known for playing Zhuge Liang 诸葛亮 in the 1994 TV adaptation of Romance of the Three Kingdoms (三国演义 Sānguóyǎnyì). Four years ago, Tang was discovered by some internet users as a perfect subject to poke fun of in guichu videos, a genre of comedy music clips “created by combining, repeating, and auto-tuning clips until they form song lyrics and melodies,” as Sixth Tone explains. Instead of taking them as an insult, Tang voluntarily fed the sensation by leveraging Bilibili, the video-streaming platform that hosts the most guichu videos on the Chinese internet, to talk to those who created and watched his guichu videos. In 2017, he proudly said in a talk show that he was thankful for playing the role of Zhuge Liang, which “established his status in the rapping community.” The statement was followed by a performance of one of his guichu songs, which was perceived by many internet users as an appreciation of their services.

It’s hard to predict whether Zhang will ever pick up enough lessons from Tang, or whether they will even work for him. The prospect looks bleak, because at the time of this writing, Liuxue is rapidly approaching the end of its viral cycle. It’s already on the way out. And when a new meme arrives to capture the attention of the weird and wacky internet, Zhang will face something more devastating than the memes he loathed: nothing at all.

Additional reading:

- 招黑的六小龄童,其实是我们大部分父辈的样子 Obnoxious Liu Xiao Ling Tong is actually how most elders look

- 从万人力挺到群嘲,只要两年 It only took two years to descend from a belove figured to a target of criticism

- 是时候了,六小龄童该上吐槽大会了 It’s time for Liu Xiao Ling Tong to appear on “Roast Convention”

- 六小龄童需要朋友 Liu Xiao Ling Tong needs friends