‘The night is thick’: Uyghur poets respond to the disappearance of their relatives

Poetry has a long and proud tradition in Uyghur culture. But it is being threatened in Xinjiang, where the Chinese state has been attempting to re-engineer Uyghur society by silencing and eliminating Uyghur cultural thought.

“I express this sorrow with my poems. The grief and longing are interlocked in all my poems.”

The horrifying stories of pain and suffering in internment camps filtering out from the Uyghur homeland have filled Uyghurs around the world with a deep sorrow. The Uyghur poet Muyesser Abdulehed said she could not help but imagine being one of the million who have spent time in these camps. The guilt of having escaped and survived is sometimes overwhelming. Many Uyghurs that I have become close to over the years have told me that survivor’s guilt invades their dreams and takes away the small joys in their lives.

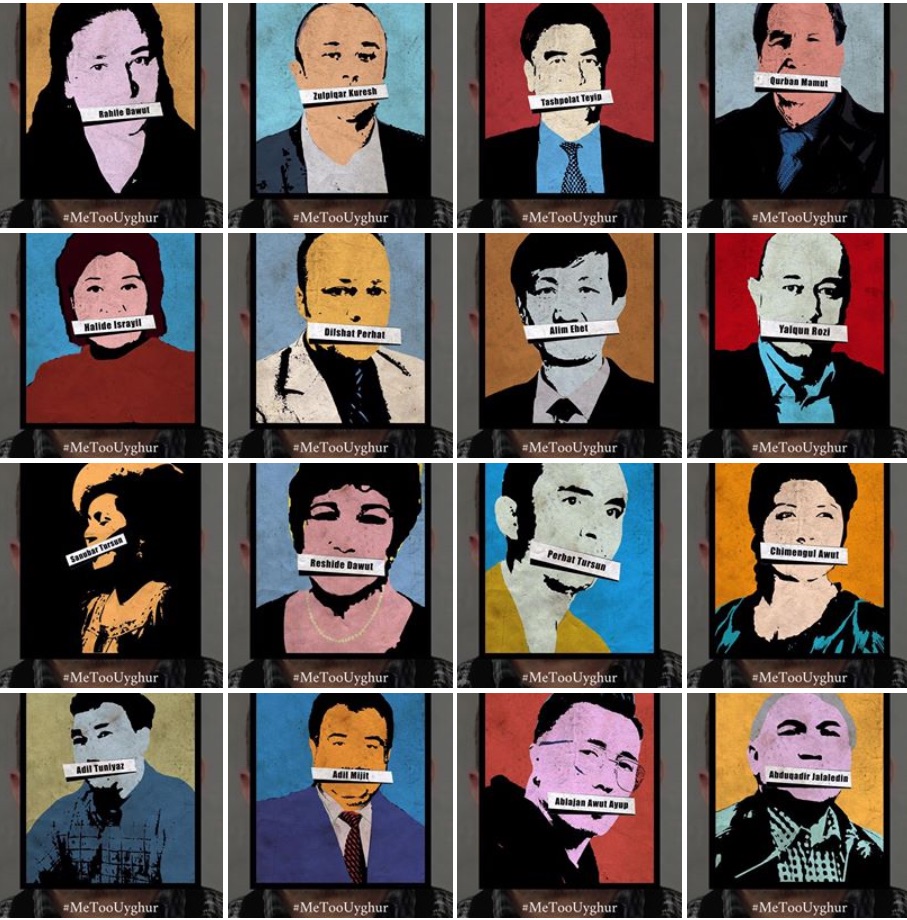

For many, these feelings of guilt, anger, sorrow, and fear coalesced during the uncertain rumors of folk musician and poet Abdurehim Heyit’s death — and his subsequent appearance in a forced video testimony. Uyghurs around the world took to social media to publicly demand the Chinese state release videos of their relatives to show that they too remain alive. They asked non-Uyghur allies to join them by posting images with handwritten signs with the hashtag #MeTooUyghur — an expression of sharing in the pain of Uyghur suffering.

“I am under investigation,” says detained Uyghur folk singer Abdurehim Heyit in the above video.

An anonymous art collective produced a series of images that centered around the silencing of Abdurehim Heyit, but also strove to represent the disappearances of hundreds of poets, musicians, and public intellectuals. This “eliticide,” as it was named recently by Henryk Szadziewski, makes clear that the Chinese state’s efforts to re-engineer Uyghur society is not simply focused on religious extremism or counter-terrorism, but in silencing and eliminating Uyghur cultural thought. Three recent poems, selected by the San Francisco-based poetry translator Sübhi, herself a Uyghur-in-exile, attempt to put words and images to these feelings of symbolic violence. They show us the way this cultural violence is connected to material, everyday forms of violence and ultimately a kind of structural violence that is shattering the Uyghur world.

Abdurehim Heyit, as portrayed by the anonymous art collective Sulu.ArtCo. On Heyit’s jacket is the lyrics of one of his most famous folk songs, “The Encounter” (Uy: Uchrashqanda). The song tells the story of a young woman who fights to survive in the face of death.

The collective has also generated iconic #MeTooUyghur images of dozens of other Uyghur public figures who have been disappeared.

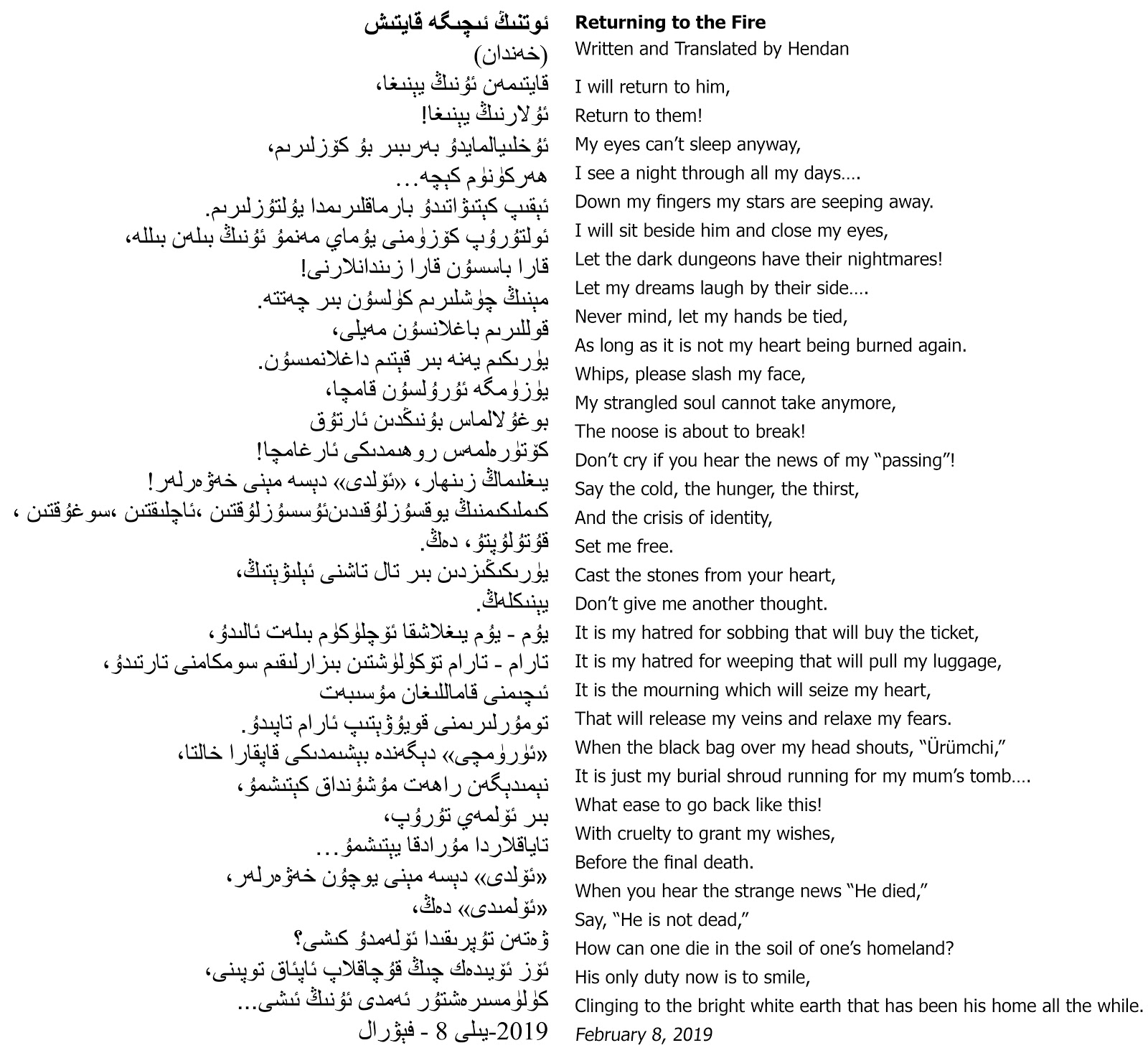

For Abdulehed, who writes poetry under the pen name Hendan, these recent events reawakened a desire to “go back and suffer with my people.” She told me that, “It is more difficult to be safe yet unable to do anything helpful for them. It was then that I had the profound realization that being dead in one’s own land is better than being alive with a strangled soul.” Abdulehed, who now lives in Turkey, lost contact with most of her relatives in 2017. The feelings of depression and loneliness have driven her to think about the meaninglessness of life. It has also pushed her to write poems about her feelings.

This poem, which centers around the image of the fire, is rooted in Sufi poetics that is central to Uyghur poetry traditions. Hendan’s love for the bright white soil of her homeland is enticing her to sacrifice her life for her beloved. She is like a moth attracted to flame. She is on the verge of no longer caring if she lives or dies, as long as she is able to run to the tomb of her mother. She just wants the pain to stop and her body to no longer be strangled by grief. As she notes at the end of the poem, her response to the rumors of Abdurehim Heyit’s death is that death is impossible if one is at home.

The Uyghur poet Abdushükür Muhemet first learned that his brother was taken to a Xinjiang “re-education” internment camp in March 2017. Since then he has lost contact with his family. He said: “Although I’m physically here in Sweden, my mind is always with them back at home. Sometimes I feel like my whole body is burning with longing. I miss my country, my relatives, my friends, and the hometown where I grow up.”

Like many of the Uyghurs living in exile whose relatives have disappeared into the vast internment camp system for Uyghur, Kazak, and other Muslims in northwest China, Muhemet has turned his longing into poetry. Uyghurs have a vibrant poetry tradition. Until the recent “re-education” effort which seeks to diminish, and in some cases, eliminate Uyghur-language publishing, there were hundreds of poetry journals across the Uyghur homeland. Nearly all Uyghur adults can recite poems by heart and many have authored their own poems.

Muhemet, who was born in Kona Sheher in Kucha County, published over 350 poems in some of the leading Uyghur-language literary journals before moving to Sweden in 2004. As an immigrant, he started a Uyghur-language journal called West Wind in 2004. Initially he envisioned that this journal would be a space for Uyghur poets and writers to continue to engage the native aesthetics of the Uyghur literary tradition, but now this space has turned into a refuge to cope with the deep, overwhelming sadness that has enveloped the Uyghur community as they see their families being torn apart back in their homeland. Muhemet said that like all Uyghur poets now, he is “sad all the time and my sadness has become sorrow. I express this sorrow with my poems. The grief and longing are interlocked in all my poems.”

The poem “Night,” featured above, was written several months after the disappearance of Muhemet’s brother, and draws out a common symbol of oppression and tyranny in Uyghur poetics. As Muhemet put it, “For hundreds of years we have been waiting for the dawn, which is a symbol for liberty and freedom, but the dawn is not here yet. We were young once, with a full head of hair. There was night then, and still is now. It is still the same, although our hair, on the other hand, has thinned.”

The grief that Muhemet feels for the loss of his brother is not only his own, personal grief. He intends the poem to express the feeling of sorrow that pervades Uyghur society. Poetry, he believes, can help express feelings of suffering that are almost impossible to represent. This, he said, is the ultimate goal of poetry. Yet, despite this goal he feels “I come up short in expressing those (feelings).”

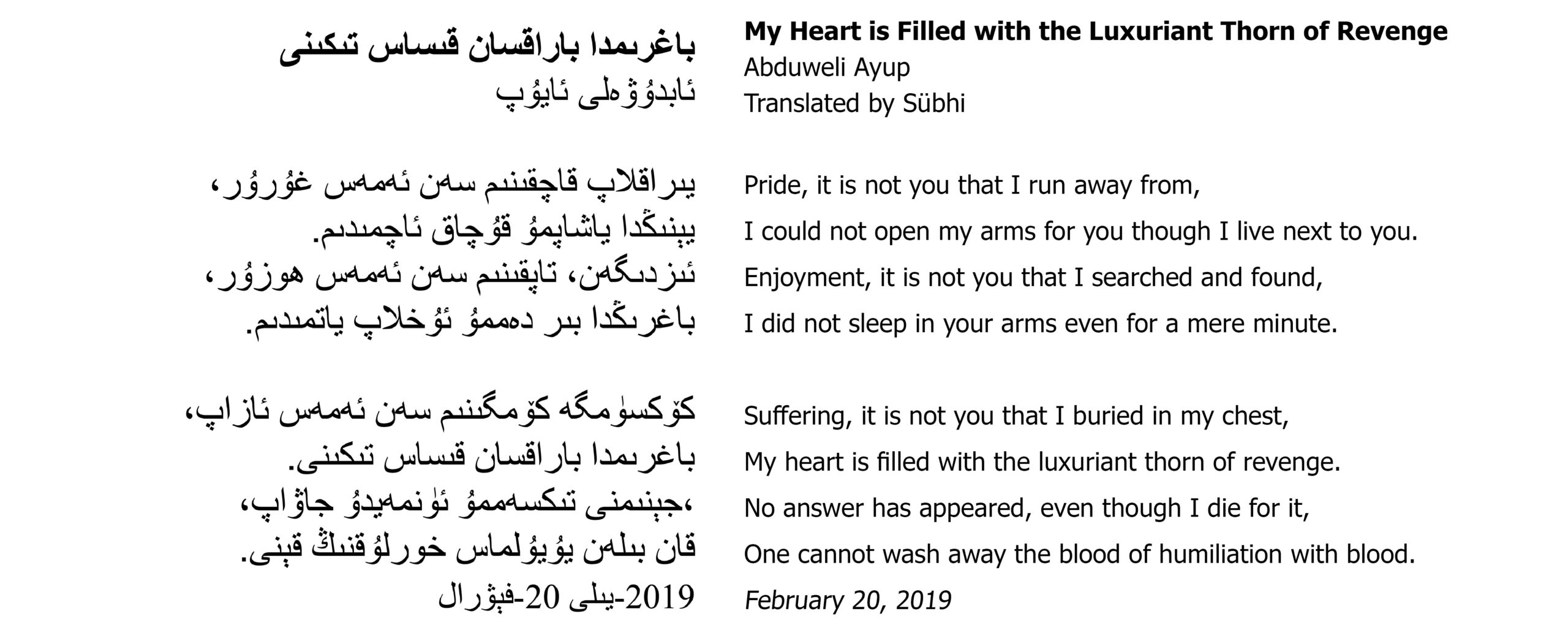

Another Uyghur poet, Abduweli Ayup, who currently lives in exile in Turkey, said he grew up near the shrine for the famous 11th-century scholar Mahmud Kashgari. In his village it seemed like everyone recited poetry. He said they “embraced poetry as a part of their lives.” He said that as a youth he memorized and recited a poem that had nearly 12,000 words, nearly 30 pages. Throughout his life, in moments of crisis, he has turned to poetry as a way of making sense of his feelings and finding a way forward.

As with Muhemet, for Ayup, this training in poetics has now become a resource for coping with his loss. He wrote the poem featured above just last month when he learned that his older sister, older brother, and younger sister had been arrested. He said, “I felt helpless, hopeless, and I heard the voice of revenge (calling out) everywhere…” He said that protecting his sisters was central to his sense of honor, dignity, and pride in every fiber of his being. He said, “I cannot protect them when they are forced to wear Chinese traditional clothes, when they are asked to perform Chinese dances, when they are forced to accept that there is no god except the Chinese Communist Party.”

In the poem he focuses on the pain he feels for them and the pain he feels for his hometown, a space that feels like a “place of comfort, just like arms of my mom.” When he is away from this place, he said he always feels as though his heart is being pulled outside of his chest. Yet despite feelings of pain pointing him toward a desire for revenge, he knows that the blood that pours from his wounds “cannot water my heart.” It will not produce any solution. He said, “We have a Uyghur proverb, ‘blood can not clean itself’ (Uy: Qan bilen qanni yughili bolmas). It means that revenge cannot solve our problems, only forgiveness can.”

Darren Byler’s Xinjiang Column is published on the first Wednesday of every month. Previously:

The future of Uyghur cultural — and halal — life in the Year of the Pig