China’s intellectual dark web and its most active fanatic

Liu Zhongjing, with his philosophy called “Auntology,” built a name for himself by espousing aggressively anti-leftist and anti-progressive views. But he’s reserved his most controversial — and dangerous — opinions for the Chinese state itself: new regionalism, de-Sinification, and support of separatist movements like those in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Xinjiang, and Tibet.

Illustration by Anna Vignet

The term “intellectual dark web” was coined, almost tongue-in-cheek, in early 2018 by Eric Weinstein, a mathematician, manager at Thiel Capital, and op-ed writer, and was meant to recognize a network of “renegades” in academia and media who reject identity politics in the name of unhindered dialectic (“free speech”). The group includes the likes of Islamophobic blogger and neuroscientist Sam Harris, former Breitbart editor Ben Shapiro, failed libertarian comedian Dave Rubin, and Jungian clean-your-room guy Jordan Peterson.

When New York Times op-ed writer Bari Weiss gave mainstream recognition to the term in her May 2018 piece “Meet the Renegades of the Intellectual Dark Web,” she includes the above names as well as others, such as UFC commentator Joe Rogan and Kanye confidante Candace Owens. But, as Weiss hinted, despite the intellectual dark web being represented by “classical liberals” that had “run afoul of the left,” below the moderate surface lurked a commentariat with a thirst for stronger stuff: white supremacy, race science, phrenology, conspiracy theories involving elite pedophile rings… Extremist figures like Sargon of Akkad, Stefan Molyneux, and Black Pigeon Speaks all wait in the even deeper shadows of the intellectual dark web, waiting to snare those introduced to milder reactionary politics by Rubin or Peterson.

In China, this intellectual dark web, or zhīshifènzǐ ànwǎng 知识分子暗网, has been embraced by internet users — but there are plenty of homegrown figures whose popularity rivals that of Jordan Peterson or Sam Harris. Like their comrades on 4chan, Chinese internet users go looking for stronger stuff, too, and it often leads them to an intellectual and blogger by the name of Liú Zhòngjìng 刘仲敬, who made a name for himself in the early-2000s on social media platforms like Douban 豆瓣 and Zhihu 知乎 (China’s version of Quora). Like Sargon of Akkad or Black Pigeon Speaks, Liu lays a scholarly, scientific veil over ideas far more extreme than anything found in the mainstream.

Liu Zhongjing, arguably, is the forefather of the Chinese intellectual dark web, and currently its most notorious stalwart.

A piece on Liu must necessarily begin with an argument as to why he merits serious treatment — if the reader has heard of him, they have likely written him off as just another illiberal crank, and, if the reader is not familiar with Auntie 阿姨, as his followers call him, it is a tough job to explain his relevance but perhaps even more difficult to lay out his ideas in a comprehensible and concise way.

At this point in history, with the intellectual dark web getting fawning profiles in the New York Times and 4chan being written up in the Washington Post for changing the course of the 2016 American general election, examples of the relevancy of extremely online reactionaries are easy to find. But it can be harder to gauge what effect the Chinese intellectual dark web has on politics in China and abroad.

The parallels with Western reactionaries are clear, though. The Chinese “right dogs” 右狗 (yòugǒu) and their battle against the “white left” 白左 (báizuǒ) is basically indistinguishable from similar online reaction on 4chan’s /pol/, The Daily Stormer, or the darker corners of Reddit: anti-semitic smears, fear of Islamization, suspicion of liberal democracy… This is no coincidence, since plenty of the right dogs have — if they aren’t already overseas — jumped the Great Firewall to follow fascist posters in the West.

Liu’s biography is hard to verify and he has never discussed his early life. Most biographies begin with a 1974 birth date and his graduation from Huaxi University in 1996, then fast forward through his time with the Public Security Bureau in Urumqi to his early retirement; in 2009, he completed a translation of Flying Serpents and Dragons: The Story of Mankind’s Reptilian Past by R.A. Boulay, a dead-serious explication of the theory that an alien race, the Anunnaki, visited ancient Sumeria; and then he began a master’s at Sichuan University, studying under Liú Yàochūn 刘耀春, and then a doctorate at Wuhan University, where he started work on A Chronological History of the Republic of China (民国纪事本末 mínguó jìshì běnmò), published in 2013 by Guangxi Normal University Press.

Liu’s later publications, including one of David Hume’s Tory revisionist The History of England and a biography of Ayn Rand, received mixed reviews (his skills as a translator have been called out repeatedly, most notably in this piece by Méi Zǔróng 梅祖蓉 for The Paper.

Apart from those more academic works and translations, Liu was sharing this thoughts online, posting on Douban as Shùjuǎncánpiān 数卷残篇 (“a few tattered volumes”). He quickly gained a following for his virulent anti-leftist and anti-progressive screeds, like this piece, cut from the collected works and reposted many times, on the white left, which manages to smear Oxfam as a leftist scheme, praises Thilo Sarrazin’s Germany Abolishes Itself, which is a book about the dangers of Muslim immigration to Germany, and explains how McCarthyism was a great idea but sowed the seeds for the collapse of American society by driving leftists into academia.

The posts between 2007 and 2014 were collected and circulated online, insurance by his followers against possible censorship. It’s in these posts that Liu first articulated a more extreme view of the world:

[The only people that] might care about human rights are people on the coasts and elite capitalists, including so-called red capitalists. They have an interest in maintaining their lucrative relationship with the West, so they care a bit. The government officials in inland China would be better off murdering this comprador class and shutting the door to the West. Once they do that, they can behave just like the Islamic State. That would simplify matters greatly. The greater world would be against them, but who is truly willing to attack the nucleus of the Islamic State? It would be a waste of money and lives.

Those posts were quickly picked up by sympathetic online communities. It was partly on Douban’s Auntie-loving Distant Evil 远邪 discussion board that the term “white left” was popularized, according to Fāng Kěchéng 方可成, academic observer of reactionary discourse.

Liu weighed in on contemporary issues like the European refugee crisis, with his pronouncements appearing on a Weibo account, Dōngchuāndòu 冬川豆, run by fans. He caught the wave of Chinese online Islamophobia early, and has remained concerned about “Islamic penetration and conquest” (“Three Pathways of Future East Asia”).

Around 2014, off the strength of his more academic work and online fame, Liu popped up in more mainstream outlets, including a fawning interview with The Paper’s Wú Qióng 吴琼, and an invitation to contribute to Gòngshì Wǎng 共识网 (a now-defunct attempt at soliciting opinions from intellectuals of various stripes — pro-market liberals and Chinese nationalists, as well as New Left thinkers and old-school Maoists — ordered offline by Party censors in October 2016). In these more mainstream outlets, he only hinted at the ideas he promoted online:

A society that has experienced Leninism cannot be unified. It would be like trying to turn fish chowder back into a fish. The conditions for constitutionalism come down to the situation in Washington. As Marx would say, they’re the big landlord, the big capitalist… It would be like Marx establishing a Jewish state on the Rhine after a Thousand-Year Reich… The truth is that all the methods that hold China together would have to be torn apart to implement constitutionalism. In order to carry out constitutionalism, there would have to be a complete refutation of Leninism… Like the Israelis, the Chinese might escape from slavery only to find themselves wandering in the desert.

What Liu hinted at in his writing for Gongshi and said explicitly in his posts on Douban was that the Chinese faced imminent collapse and would be replaced by dozens of smaller states, organized around language, ethnicity, and geography.

Liu Zhongjing’s philosophy — Auntology — borrows heavily from the work of Oswald Spengler (1880-1936) and other thinkers of the Konservative Revolution of interwar Germany. The key to understanding Liu is Spengler’s 1918 The Decline of the West, translated into Chinese as Xīfāng de Mòluò 西方的没落. Spengler posited eight “High Cultures,” beginning with the Babylonian and ending with Western Europe and the United States. The previous seven High Cultures all went into decline and, Spengler argued, the Occident, at the time wracked by war, epidemics, and poverty, was on its way out, too:

At this level all civilizations enter upon a stage, which lasts for centuries, of appalling depopulation. The whole pyramid of cultural man vanishes. It crumbles from the summit, first the world-cities, then the provincial forms and finally, the land itself, whose best blood has incontinently poured into the towns, merely to bolster them up for awhile. At the last, only the primitive blood remains, alive, but robbed of its strongest and most promising elements. This residue is the fellaheen.

For Liu, China is no longer a nation, but the remains of a nation, peopled by the fellaheen — the word in Arabic is فلاحين, close enough to the Chinese nóngmín 农民, or the English “peasant,” but Spengler uses it to refer to a fallen class that has been robbed of national destiny. The fellaheen (fèilā 费拉 in Chinese) are a post-historical people (史后之人 shǐ hòu zhī rén), and Liu marks the end of that history around the Qin Dynasty (221 BC–206 BC).

Liu is fond of a line from Spengler’s The Decline of the West that states: “I am convinced that the nations of China which sprang up in members in the middle, Hwang Ho [Yellow River] region at the beginning of the Chou dynasty [Zhou Dynasty]…were in their inward form more closely akin to the peoples of the West than to those of the Classical and the Arabian worlds.” Whether his reading of it is correct or not, he sees it as proof that the Qin wars of conquest that unified the Warring States resulted in the extinction of “cultural nations” (wénhuà mínzú 文化民族, or Kulturnation, as Spengler calls them in the original) and replaced them with a fellaheen nation (fèilā mínzú 费拉民族), disconnected from its cultural roots.

The only future for the people that live under an empire of fellaheen (fèilā dìguó 费拉帝国) is a process that he calls “ethnic invention” (mínzú fāmíng 民族发明) — basically, concoct a local Culture (capitalized after Spengler, who saw Culture as the seed and Civilization as the plant into which it grows). The process involves de-Sinicization and rejection of Han culture (tuōzhī 脱支, “to escape Shina,” borrowing the derogatory archaic Japanese term for China). The need to build new tribal nations is made all the more pressing by Liu’s prediction of a Great Flood (Dàhóngshuǐ 大洪水), an impending apocalyptic event that will see much of the world’s central governments collapse.

This is a massive simplification, trimming Liu’s ragged bush of fascist historiography, Christian millenarianism, conspiracy theory, and anti-left extremism into a tidy landing strip.

In a criticism of Liu, “Liu Zhongjing: the crumbs of a worthless man in the clothes of a king,” published on resolutely anti-progressive Chángjiāng Zátán 长江杂谈, the anonymous writer attempts to sum up Auntology this way:

Liu Zhongjing believes that the Chinese, beginning from the administration of the Qin Dynasty, had become a fellaheen nation. A fellaheen empire has only population, not people with an ethnic identity. Therefore, there is no Han ethnic group because the supposedly Han people are fellaheen. Fellaheen is not an ethnic identity, so they are simply slaves laboring under imperial bureaucracy. Also, he supports the idea of “various Chinese nations,” so in Sichuan, there’s a Basuria, in Hubei a Jingchuria, in Guangdong a Cantonia… It’s ridiculous, isn’t it? This is the kind of raving you might hear in a mental hospital.

The anonymous writer is one of many that sympathize with Liu’s attacks on progressivism but feel that the disintegration of the People’s Republic is going much too far.

But Liu’s ideas on de-Sinicization, ethnic invention, and a coming collapse, although not always particularly original, have their adherents. Following Liu’s own invented state of Basuria or Bāshǔlìyàguó 巴蜀利亚国, his followers have begun inventing their own.

“Jacob Pius,” who goes by @Yuyencian on Twitter, recently posted a “Map of the national independence movement in Far East” (above). The map includes Liu’s “ethnic invention” of Basuria as well as other polities, including Yehetland, Komeseland, Goetland, Tshiechuria, Hakkaland, and also East Turkestan and Tibet. For Liu and his followers, these proposed nations organized around ethnicity and language are part of a struggle for independence from the People’s Republic of China and other states in Asia.

The map’s divisions obviously borrow from pre-PRC borders and the country names refer to regional titles that date back millennia. Liu’s Basuria is an attempt, at least in name, of resurrecting the states of Ba and Shu, both located in what is now Sichuan Province and both conquered by the Qin. Yuyencia (Yōuyànxīyà 幽燕西亚), which covers territory now occupied by Hebei, Beijing, and Tianjin, also refers back to two defunct jurisdictions, both part of the Nine Provinces. Goetland’s Chinese name Wúguó 吴国 is borrowed from the Kingdom of Wu, and its English name attempts to recreate the way speakers of that region’s language would pronounce the first character of the kingdom.

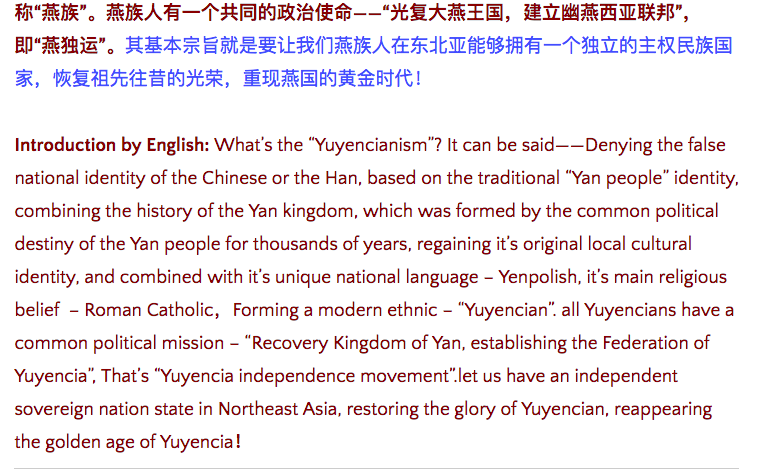

These movements can be hard to take seriously — Yuyencia’s website, for example, describes their proposed nation as having a “unique national language,” called Yenpolish, and a national religion, which will be Roman Catholicism.

Yuyencian independence leader Jacob Pius is serious, though, about what he sees in the future of the PRC and Western liberalism.

Liu has praised regional nationalist movements on Twitter, and has also become a supporter of more legitimate nationalist or separatist movements, like those in Hong Kong and Taiwan (he’s become a fan of Tsai Ing-wen 蔡英文). His views on other separatist movements in Xinjiang (and Tibet) are more complicated and informed by his understanding of regional history:

What’s happening in Xinjiang is a tragedy. If we look at things from a historical point of view, Xinjiang, since ancient times, has had a closer relationship with Central Asia and Southwest Asia than East Asia. If we go back to the earliest periods of Chinese history, the Zhou and Han Dynasties, for example — the ethnic composition was different. What is now Gansu and the Hexi-Gansu Corridor used to be populated by people related to Persians. Their language, culture, and skin color was similar to Persians. There were some that even had blond hair and blue eyes. An Lushan and the Nine Tribes of Zhaowu [Sogdians] in the Tang Dynasty were of Persian descent, too. Even mainstream archeologists say that the name Zhaowu comes from those people that lived in Gansu, and they would have had blond hair and blue eyes, the same race as the Beauty of Loulan [a Caucasian mummy discovered in 1980 in Xinjiang]. They didn’t have Mongolian ancestors.

All the racial theory and shaky history aside, Liu argues that Xinjiang and Tibet are both occupied territories that can only remain part of the Chinese empire through military force. His idea of new regional nationalist movements solves the problem, although it is most unconcerned about both regions: those places should and will go their own way, with Tibet likely becoming a separate state and Xinjiang broken up into various ethnic enclaves with close ties to Central Asian and Near East powers.

Jacob Pius shares Liu’s belief in a coming collapse and antipathy toward left-wing politics. He explained via email that he sees right-wing politics in the West as an attempt to preserve a civilization from decline, while “the left is anti-religious, places individuals at the center of their own world, and advocates the violent overthrow of the old regime and its replacement with a powerful state, a planned economy and personal freedoms…such as homosexuality.”

Many of the de-Sinicizers that followed Liu Zhongjing have converted to or are enthusiastic about Christianity. In recent years, Liu has reportedly converted to Christianity, following through on his previous enthusiasm for the church, and is possibly involved in the Shouters sect, although he has been cagey about specifics. Jacob Pius describes himself as a Catholic traditionalist. Before the “ethnic invention” of Yuyencia, Jacob Pius hoped to leave the Chinese Mainland, emigrate to the West, lead a “regular life of faith,” and perhaps get involved in “what you might call right-wing political movements, like French monarchism.”

For those red-pilled by Liu Zhongjing, there is hope in de-Sinicization and the sometimes frivolous project of ethnic invention, but there is also a wider fascination with Liu’s ideas, even among the yíhēi 姨黑 (a portmanteau of “Auntie” and a term for “negative fans”) in the black pill — Chinese civilization will not last and the West has been doomed by progressive politics. (In The Matrix, those who took the red pill see reality for what it is; those who choose the blue bill remain in blissful ignorance. This has become a cultural meme. The idea of a more extreme black pill, which was for those who chose extreme nihilism and despair, was the invention of internet posters who wanted to take a step beyond a red/blue dichotomy.)

As of late-2018, Liu had seemingly relocated to the United States, and now posts his predictions and musings to tens of thousands of followers on his Twitter account and less-trafficked accounts on Youtube and Medium.

The rumored jump to the U.S. is a wise move, at least for legal reasons: what Liu Zhongjing is engaging in amounts to splittism. Leaving aside the more well-known strike-hard campaigns against independence activists, smaller regional attempts to secede from the PRC have also ended poorly, including Shí Jīnxīn 石金鑫 and his Great China Buddhist Kingdom 大中华佛国, a failed 1983 plot that saw the new “dynasty’s” prime minister, Lǐ Pīruì 李丕瑞, getting the death sentence; and Lǐ Chéngfú’s 李成福 Heavenly Kingdom of Everlasting Satisfaction 万顺天国, a scheme that involved separatist moles within the PLA and a plan to stage an uprising in Beijing.

Some of his followers have made the jump, as well.

Happy New Year(year of pig) pic.twitter.com/l0R5c8dGK1

— Augustus (@russomanchu) February 8, 2019

Lǐ Shuò 李硕, who rumors suggest was harassed by the authorities after his declaration of Manchu independence, made the jump to the U.S. a few years earlier than Liu and seems to be settling in well, despite earlier rumors that he was cleaning Starbucks bathrooms. His Twitter claims: “I coined the term #Baizuo white left.” Posts range from praise of Zhao Benshan and Hitler to flicks of his gun collection.

For Liu, it seems to have always been the end goal to bring his vision to the West.

He sees himself as a modern-day Ayn Rand, an ideological refugee who was welcomed with open arms in the United States. In Liu’s interview with The Paper in 2014, he made his connection to Rand more explicit:

When she got to America, she never stopped preaching American values. [She was] like the barbarians that came to Rome who had a deeper knowledge of its achievements than the Romans themselves did and were willing to give their own lives to defend it… The things that she had been longing for for so long, she couldn’t bear to see some savage forces destroy them. I can completely understand that feeling.

The long-term prospects for Liu in the United States are unclear. Běidàfēi 北大飞, a New Left-type debunker of fake news, laughed uncontrollably when asked if Liu might be a new Rand. He made the point that reactionaries like Liu are less interested in the West than in events at home, echoing points that Chenchen Zhang made in her writing on right-wing populist discourse on Chinese social media: even jargon (like “white left”) that would seem to fit in a tradition of Western right-wing populism is more about making statements on Chinese identity.

大蜀民國祝賀滿洲國人民在反恐復國的鬥爭中日益強大⋯⋯ https://t.co/jfKzyj1tDr

— Zhongjing Liu | 劉仲敬 (@LiuZhongjing) March 1, 2019

Liu has mostly stuck to his native tongue, despite taking to American social media platforms, suggesting that his Randian goals might be lost in translation. His engagement with Twitter is mostly limited to retweets of ethnic identity activists (the above tweet to the Concordia Association of Manchuria reads, basically, “Basuria congratulates the people of Manchukuo in strengthening their fight to recover their nation”).

Whether or not Liu makes any progress in bringing the American barbarians around, his ideas and jargon remain present and potent on the Chinese-language internet. He’s mostly flown under the radar of internet censorship, with his collected Douban posts still circulating on the platform, through the Dōngchuāndòu 冬川豆 Weibo account, and there is lively discussions of his philosophy on the Zhihu message board and the Zhuanlan 专栏 blogging service. Since the discovery of Chinese troll farms churning out social media posts, it’s easy enough to imagine the jargon and rhetoric of the king troll of the intellectual dark web being weaponized, too.