1919 to 2019: A century of youth protest and ideological conflict around May 4

Xi Jinping heads a party born out of a youth movement, and he’s now determined to stamp out anything that could threaten to replicate it.

When Communist Party General Secretary Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 spoke before a high-level education conference in late 2016, he set off a far-reaching ideological crackdown in the country’s universities. The supposed threat was “Western” liberal values, to which Xi put forth a mandatory antidote: “Higher education must be guided by Marxism,” he said, dictating that the philosophy lay an ideological foundation for students’ lives.

Two years later, authorities went about suppressing dozens of students who took him literally.

Over the past year, students and recent graduates from China’s top-tier universities have taken to the streets in multiple cities under the banner of Marxism on behalf of feminism, workers’ rights, and their own ability to form groups devoted to the ideology. In a development that should surprise no one who has tracked China’s political environment in recent years, many of those involved were then detained, followed, interrogated, threatened, assaulted, or simply disappeared.

While these events are new, they represent the continuation of a conflict that spans more than a century in China — one from which the Communist Party itself was born but to this day has yet to resolve; a conflict over who gets to define the very concepts of “socialism” and “democracy,” and who gets to drape themselves in the banner of these seemingly contradictory — but often intertwined — ideologies.

Just like the events that are transpiring today, the conflict began at Peking University (PKU, or běidà 北大).

New Youth

In early May of 2018, Xi Jinping celebrated two back-to-back and interwoven occasions: the 99th anniversary of the May 4 Movement, now celebrated as China’s “Youth Day,” and Karl Marx’s 200th birthday on May 5. One of the stops on his multi-day commemoration was PKU, where he noted that the school was the cradle from which Marxism started to spread in China, and that it played a key role in the Communist Party’s founding.

Xi was right, but the road from Marxism’s roots at the university to the Communist Party he now heads was far from straight. In many ways, the student Marxists being suppressed today are a closer embodiment of those roots.

In the mid-1910s, Peking University was at the center of the New Culture Movement, which emerged as China’s newly-established republic was faltering and failing to deliver the modernization that many had long hoped for. Those who had studied abroad were bringing back ideologies from France, England, Japan, Russia and the United States, and igniting debate on China’s very social and cultural foundations.

One of the most prominent figures of the movement was the Japanese-educated Chén Dúxiù 陈独秀, who founded the journal New Youth in 1915, and later became dean of Peking University’s School of Arts and Letters. Initially called The Youth Magazine (青年杂志 qīngnián zázhì), Chen’s monthly changed its name to New Youth (新青年 xīn qīngnián) in 1916, and became one of the most influential publications of the period. Thousands of young readers eagerly awaited writings ranging from contributors like the American-educated liberal philosopher Hu Shih (胡适 Hú Shì) to a young PKU librarian’s assistant named Máo Zédōng 毛泽东.

The journal took a critical stance on Confucianism and traditional Chinese culture while publishing articles that promoted “Western” notions of rule of law, individualism, individual rights, and women’s liberation. In 1918, Chen Duxiu himself wrote in New Youth that “Mr. Science” and “Mr. Democracy” were the only two gentlemen who could “save China from the political, moral, academic, and intellectual darkness in which it finds itself.”

In 1919, the movement took a dramatic turn. Shandong peninsula, which had been seized by Germany two decades earlier, was turned over to Japan rather than China under the Treaty of Versailles that ended World War I. It infuriated Chinese students and intellectuals who saw it as yet another example of their feeble corrupt government standing idly by, while foreign powers inflicted humiliation upon China.

On May 4, intellectuals and students from Peking University led student protests in the streets of Beijing and Tiananmen Square. The movement spread throughout the country and across social groups, leading to anti-Japanese boycotts and even a general strike in Shanghai that paralyzed the city.

In the wake of the movement, some of the New Culture leaders began to second-guess the influences they’d derived from the liberal democracies that had betrayed China with the Treaty of Versailles. The movement fractured, with moderate liberals like Hu Shih parting ways with leaders like Chen Duxiu who moved more radically to the left and drew inspiration from Russian Bolshevism and the October Revolution.

By then, Lǐ Dàzhāo 李大钊, a librarian at Peking University, had started a Marxist study group at Peking University, and he and Chen had run a special edition of New Youth devoted to the philosophy. “China’s governmental revolution in the next couple of years absolutely cannot effect a Western-style democracy,” Chen had decided by 1921. “It would be best to undergo Russian Communist class dictatorship.”

That year, Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao founded the Chinese Communist Party.

But the party that Chen co-founded would soon leave him behind. Its alignment with Russia continued even as Joseph Stalin consolidated power and instituted a ruthless totalitarian brand of socialism — a development that put Chen at great unease. By the late 1920s, he found himself at odds with Stalin and the Soviet-dominated Comintern that now wielded major influence over China’s fledgling Communist Party. In 1927, Chen was pushed out of his position as general secretary of the CCP and two years later was expelled outright from the party he had founded.

Over the following years, Chen became more firmly anti-Stalinist. Though he still feared the excesses of capitalism and remained a socialist, his admiration of democracy re-emerged — which he didn’t find to be a contradiction. Since the height of the New Culture Movement and early discussions of Marxism in China, many had believed that the freedoms, individual liberties, and government accountability inherent in democracy could be fused with the egalitarianism and proletarian empowerment that Marxism offered. In 1919, an article in New Tide monthly, another publication associated with the New Culture Movement, had posited that “after the new revolution, democracy and socialism will surely coexist.” (New Tide 新潮 xīn cháo was sometimes called The Renaissance in English.)

As Chen Duxiu lived out his final years in a rural Sichuan village, he again became a strong proponent of independent courts, a free press, open elections, and competing political parties. But by then, Chen’s beliefs were of little consequence as Mao Zedong controlled the growing Communist Party. Chen died in obscurity in 1942 — seven years before the party he had founded seized total control of China. After it took power, the Party established what it called a “People’s Democratic Dictatorship” and ruled with the Stalinist iron fist that Chen had feared.

Capitalism and Socialism with Chinese characteristics

In the late 1970s, after three decades of the grinding poverty, violent political campaigns, and ideological dogma that marked the Mao era, China was ready for pragmatic reform. It got it under the stewardship of Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平 when he launched “Reform and Opening Up” and tacitly began to embrace the evil that the Communist Party had been railing against for nearly six decades: capitalism. In what would be one of many ideological contortions to come, the Party oversaw an authoritarian market system while continuing to push Marxist ideology. It was dubbed “Socialism with Chinese Characteristics.”

This period of economic reform led China into uncharted waters, and there was uncertainty about what it meant for the country’s political future. Even the highest levels of the Communist Party couldn’t agree on whether the country would continue under a hardline one-party system, begin to democratize, or find some middle ground. These questions broke out into the open in an age of intellectual curiosity and debate that hadn’t been seen since the New Culture Movement. Once again, students returning from overseas were bringing back fresh ideas, and single articles or television programs could stir up nationwide discussions.

But by the mid-1980s, growing pains from China’s reforms were emerging. Inequities, nepotism, and corruption were running rampant in the growing economy. Workers who had thought they had guaranteed jobs for life suddenly had to fend for themselves, and were often woefully unprepared to do so. Students graduated only to learn that if they didn’t have powerful connections, they would be shut out from the best jobs. Government officials took advantage of mixed pricing systems to enrich themselves and inflation soared. The Communist Party’s sole source of legitimacy — Marxist egalitarianism — was crumbling.

But much like the May 4 Movement, it was grievances with Japan that first began to signal real trouble for the Chinese government. By 1985, Japan had been flooding China with aid loans and investment, partly to access the Chinese market and its natural resources. Some Chinese saw this as the cause of the mounting inflation, and blamed domestic leaders for selling out the country. Salt was rubbed into the wound in August of that year when Japan’s prime minister visited the infamous Yasukuni Shrine that commemorates some military “martyrs” convicted of war crimes against China.

In the preceding months, there had been a number of isolated student demonstrations at universities protesting poor food, high fees, overcrowded dormitories, inadequate medical services, and nighttime power cutoffs. But with this national affront, they were galvanized to take on bigger issues. Anti-Japanese big-character posters started appearing at universities, with some including repudiations of domestic leaders. One read, “Commemorate the [Chinese] martyrs, overthrow the corrupt cadres, strengthen the nation scientifically, and respect knowledge.”

Down with Japan and black devils, protect human rights

On the September 18 anniversary of Japan’s invasion of Manchuria, hundreds of college students marched on Tiananmen Square to protest. Over the next several months, more student protests erupted that were ostensibly aimed at Japan, but more and more they were turning toward China’s domestic situation and putting authorities at unease. Another Tiananmen Square demonstration was planned (but ultimately thwarted) to mark the 50th anniversary of the now little-remembered December 9th Movement of 1935, where thousands of Chinese students had protested the Kuomintang government for its failure to resist Japanese aggression and its unwillingness to embrace freedom of speech, press, and assembly.

Once again, these calls for more liberal freedoms coincided with left-wing inclinations. There were reports of a “new left” beginning to emerge — its membership made up of young people “who have not gone through the Cultural Revolution, who hate nepotism and bureaucracy, who feel that Marxism is the ultimate in China and that the country should go back to the real thing,” according to a Los Angeles Times report at the time. In 1986, two Peking University students were sentenced to seven years in prison after calling for the overthrow of the Communist Party and saying China should return to “true Marxism.” China’s current leaders, they asserted, were “undemocratic” and “not true Marxists.”

Amid these criticisms, People’s Daily even invoked what one reporter referred to as the “oft-forgotten name of Mao Zedong” in an effort to win the allegiance of the youthful protesters. It ran a supposed speech by Mao about the December 9 Movement saying that students and intellectuals must unite behind the Communist Party in order to “follow the right road.”

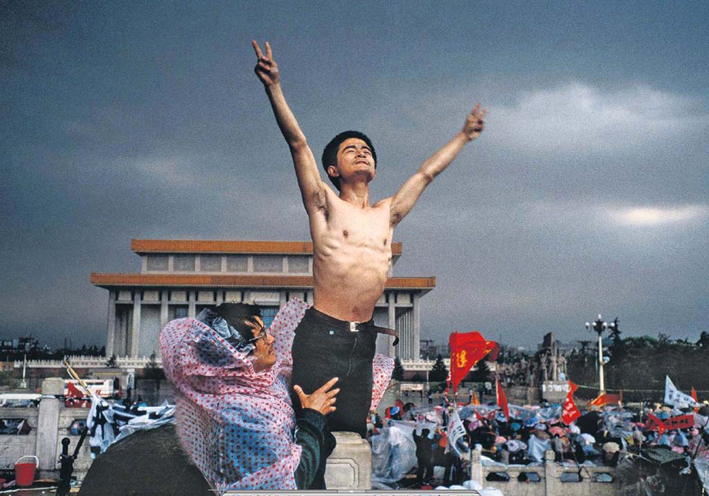

Throughout 1986 and 1987, more protests broke out that had morphed almost completely toward calls for domestic political reforms. These were then reignited in December 1988 when anti-African protests emerged in Nanjing after a scuffle between African students and Chinese security guards led to false rumors that Africans had killed a Chinese man and kidnapped Chinese women. Already frustrated by how foreign students seemed to enjoy better treatment than their local counterparts, Chinese students took to the streets where they mixed chants like “down with the black devils” with “protect human rights” and other calls for political reform. Then, with the death of popular reformist leader Hú Yàobāng 胡耀邦 three months later and the large gatherings it facilitated, the penultimate showdown began in Tiananmen Square.

While the Tiananmen Movement tends to be remembered as a “pro-democracy protest,” it was much more multi-faceted, with some groups of protestors contradicting one-another. Many workers thought reforms had moved too fast, while students thought they were going too slow. Some wanted a complete “Western-style” democratic overhaul of the political system, but more just wanted liberal reforms around the edges. There were also those who wanted a return to a purer form of socialism. Participants in the movement ranged from eventual Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liú Xiǎobō 刘晓波 to Confucius Peace Prize founder and ultra-left-wing Maoist Kǒng Qìngdōng 孔庆东.

Like the May 4 Movement before it, many of the Tiananmen protesters thought liberal reforms like freedom of press and speech, checks and balances, and more government accountability were perfectly compatible with a socialist framework. It was, after-all, the death of a popular reformist leader inside the communist system that had galvanized them in the first place.

Nothing to my name

Another issue that united many protestors, particularly among the youth, was personal freedom. In the 1980s, China still maintained its danwei work unit system, which was the Communist Party’s most direct means of monitoring and controlling its citizens. Under the system, people were assigned to work units that controlled their pay, housing, and other benefits, and had to grant permission for travel, marriage, or childbearing. The danwei were also tasked with implementing and enforcing party dictates, which included — among many other things — monitoring women’s menstrual cycles to ensure they were complying with the family planning policy (and obligatory pre-marital chastity). For those that lived under the danwei system, the eyes and hands of the state were a permanent fixture of everyday life.

Between the still invasive personal restrictions and diminishing paths to success in an increasingly materialistic society, many young people felt like downright losers. During the protests, the song “Nothing to My Name” by 27-year-old rock star Cuī Jiàn 崔健 became the movement’s unofficial anthem. Depicting a woman who ridicules her admirer for lacking material wealth, the song captured the disillusionment that many youth felt. “[It] expresses our feelings,” student leader Wú’ěr Kāixī 吾尔开希 recalled years later for the documentary The Gate of Heavenly Peace. “Does our generation have anything? We don’t have the goals our parents had. We don’t have the fanatical idealism our older brothers and sisters once had. So what do we want? Nike shoes. Lots of free time to take our girlfriends to a bar. The freedom to discuss an issue with someone, and to get a little respect from society.”

In what would be coincidental timing that added fuel to the protests, the 70th anniversary of the May 4 Movement fell at the height of the Tiananmen Movement. This represented one of the most contentious ideological conflicts of protests: who could claim to be the true successors of May 4?

The Communist Party, which was born out of the movement, claimed it was the vanguard of May 4, arguing that the student protestors were more reminiscent of the fanatical Red Guards of the Cultural Revolution. Protestors, however, claimed it was they who were carrying on the May 4 spirit of admonishing a corrupt and ineffective government that had lost its way. On the anniversary, students unveiled a “New May 4 Manifesto” — read aloud by Wu’er Kaixi — that revived many of the themes from the movement 70 years earlier. “The Marxism espoused by the Chinese Communist Party cannot avoid being influenced by the remnants of feudal ideology,” it read. “Although it has emphasized the the role of science, it has not valued the spirit of science: democracy.”

In the end, one side of the showdown possessed the machinery of the military, and the other a fracturing coalition with an incoherent set of demands. After a power struggle at the highest level ultimately neutralized leaders sympathetic to the protestors, the movement’s fate was sealed. It could have been broken up with non-deadly force, as many had been before it, but that would have only been a short-term fix. Deng Xiaoping instead allegedly rationalized a massacre, saying, “Two-hundred dead could bring 20 years of peace to China.”

On June 4, 1989, machine guns and tanks abruptly ended China’s 20th century tradition of youth protest movements. As the last group of students stood in the center of Tiananmen Square with gunshots still audible from the surrounding streets, they sang one final song before being dispersed: the international socialist anthem, “The Internationale.”

The Century of Humiliation, and a new bargain

Five days after the Beijing massacre, Deng Xiaoping addressed a group of military leaders who had participated. “During the last 10 years our biggest mistake was made in the field of education,” he told them. “Primarily in ideological and political education — not just of students but of the people in general. We didn’t tell them enough about the need for hard struggle, about what China was like in the old days and what kind of a country it was to become.”

The Tiananmen Movement laid bare the untenable contradiction between the Marxist ideology that the Communist Party continued to stake its legitimacy on, and the capitalist reality that was unfolding in the country. So it reached back to a concept that had first been used in 1915, and later invoked by Chiang Kai-shek (蒋介石 Jiǎng Jièshí) to rile up nationalistic support: national humiliation.

Rather than pushing for the workers of the world to unite under proletarian internationalism and class struggle, the Communist Party began pushing Chinese nationalism and historical victimhood. The new narrative went like this: China was the world’s preeminent power and an exceptional peace-loving civilization for 5,000 years, until a succession of foreign aggressors brought the country to its knees during a brutal “century of humiliation” (1840-1949). Not until the Communist Party vanquished the Japanese invaders and emerged victorious in the civil war did the country begin to regain its footing.

This “Patriotic Education Campaign” — rolled out between 1991 and 1994 — watered down Marxist ideology to only the elements that suited the Party’s new needs. At the same time, it began emphasizing in bloody detail the extent of foreign-inflicted atrocities. Events like the 1937 Nanjing Massacre by the Japanese army — which had been almost completely ignored in official records to that point — became front and center.

The implication of the Patriotic Education was that the Communist Party had been, and would continue to be, the defender of the nation’s interests and dignity both at home and against ever-present “hostile foreign forces.” Never again would it be caught on the wrong side of nationalistic angst — it would instead harness it. The Party, and only the Party, could claim to ward off chaos, make China strong again, and bring about a “national rejuvenation” to regain the country’s rightful position as the world’s top dog.

But making China great again would take more than just rhetoric — it would need to continue developing quickly in order to catch up to the West.

In 1992, after years of post-Tiananmen stagnation, Deng Xiaoping went on his famous “Southern Tour” to signal that economic reforms would continue. And continue they did. In the subsequent years, China’s economy started privatizing in earnest and shutting down thousands of inefficient state-owned enterprises. From the Party’s perspective, this painful restructuring was a risky gambit — it resulted in tens of millions of laid-off workers — but it paid off. Per capita GDP tripled between 1990 and 2000. Over the following decade, as China joined the World Trade Organization and integrated further with the world economy, it multiplied even faster: four-and-a-half-fold from 2000 to 2010.

The emergence of the private economy was the death knell for the danwei work unit, and it gave ordinary citizens more wealth and personal freedom than they had ever had. Young people got their Nike shoes, they got bars to take their lovers to, and Big Brother all but became invisible to most. Now that the very tangible desires that protestors had demanded at Tiananmen were satisfied, the more abstract political questions were put back on the shelf. The Party had tacitly offered a grand bargain to the people: You can have unprecedented social and economic freedom, as long as you don’t ask for political freedom.

This bargain appeared to succeed beyond anyone’s wildest imagination. Hundreds of millions migrated from grinding rural poverty to find new wealth and opportunities in the cities. Skyscrapers and bullet trains sprouted up that made even developed European and American metropolises look quaint by comparison. Millionaires and billionaires emerged to enjoy lives of opulence that would make Gatsby blush. The modernization that had eluded China throughout the 19th and 20th centuries seemed to have finally arrived. The exclamation point came when the world looked on with awe at the 2008 Beijing Olympics, and then was humbled further just two weeks later when the Global Financial Crisis hit. The West fell into economic despair as China continued to chug ahead with double-digit growth.

That year, rock star Cui Jian compared China’s new young generation to the one that had belted out his songs in Tiananmen. “The earlier generation had a very clear direction,” he told VICE. “You know, liberation, revolution, whatever. The next generation doesn’t believe in anything — just in what I can get, what I can control in my hand. I think money is most controllable.”

But Cui may have spoken too soon. By this time, Tiananmen was now a generation in the rearview mirror. Those who had lived through the massacre had perhaps been scared away from protest and pacified by economic opportunity, but a new generation was now coming of age. Deng Xiaoping’s morbid gamble that “two-hundred dead could bring 20 years of peace” had essentially been validated, but it was nearing its expiration date.

Cracks in the bargain

Those born in the late 1980s and 1990s didn’t remember the chilling message that the June 4 massacre was supposed to send. They didn’t remember the danwei system and the ever-looming threat of Big Brother, ready to hammer down any nail that stuck out. They didn’t remember the political witch hunts or insufferable hardship that their parents lived through. They were consuming foreign culture, becoming unapologetic individualists, and beginning to take stability, personal freedom, and economic opportunity for granted. Now, they wanted more.

In 2007, what was probably the first unsanctioned demonstration since 1989 involving tens of thousands of protestors began to unfold. The setting was the coastal city of Xiamen, and the grievance was a massive proposed petrochemical plant. It promised to double the city’s GDP, but concerns over a supposedly dangerous chemical that it would produce outweighed the economic benefits to many residents. After a text message of unknown origins exaggerated the dangers posed and circulated among as many as a million locals, more than 10,000 people took to the streets wearing yellow ribbons and holding signs lambasting the project’s developer and local Communist Party secretary.

The crowds were dominated by young faces — many of them high school and college students. In a bid to curtail the demonstrations, the government dispatched paramilitary forces to guard the gates of Xiamen University, but that only caused more protests to break out there. Ultimately, the people got their wish: the plant was booted out of town.

The Xiamen demonstrations were a watershed moment that illustrated how Chinese becoming disgruntled by the side-effects of breakneck growth could band together through technology. In the following years, that newfound public power would shake the command-and-control model of rule that the Communist Party had grown accustomed to.

While the Xiamen movement had been organized primarily through text messages, a new tool was emerging. In the three years following the protests, internet penetration more than doubled from 16 percent of China’s population to 34 percent. Then 2010 saw another game-changer enter the scene to supplement it: Sina Weibo.

The Twitter-like microblog, overwhelmingly used by those born after 1980, enabled environmental protests even larger than those in Xiamen to quickly mobilize in cities across the country — including Kunming, Shifang, Maoming, Chengdu, and Ningbo — some of which turned violent. The platform likewise helped galvanize labor protests, which were growing exponentially. Factories strained by inflation and falling exports to Europe and America collided with a second generation of young workers becoming more demanding about their wages and treatment.

Weibo was also rallying people around even more politically sensitive issues. In late 2010, a 22-year-old man struck two college students (one of whom died) with his car while driving drunk. When later stopped after fleeing the scene, he name-dropped his father — the deputy director of the local security bureau. “Go ahead, sue me if you dare,” he said. “My father is Li Gang!” (我爸是李刚 wǒ bà shì Lǐ Gāng)

The quote became an enduring internet meme that encapsulated out-of-control official privilege, which was becoming a sour point as wealth inequality soared. Over the following years, countless more stories spread on Weibo that illustrated corruption, social injustice, government cover-ups, extravagance of the rich, and Dickensian tales of the country’s most vulnerable and forgotten. Some of these issues were perhaps already past their nadir, but the internet was exposing them to the masses for the first time.

In a single generation, China had gone from a poor, quasi-socialist society to a hyper-materialistic crony-capitalist one, and the gap between the winners and losers of that transition had never been more visible. The feeling was especially acute for China’s youth, who had not been around to capitalize during the boom years, and were now recognizing that they were largely tethered to the social class they were born into. College students were becoming particularly jaded. A massive expansion in university enrollments a decade earlier had led to severely devalued degrees, and the outskirts of major cities were filling with so-called “ant tribes” — swaths of graduates living in poverty conditions, unable to find work.

During this time, the slang term “diǎosī” ( 屌丝 — “penis hair”] came into vogue among Chinese youth. Reminiscent of Cui Jian’s “Nothing to My Name,” it was initially used to describe young men who were societal losers with no money, no connections, and no prospects, and thus, no hope of ever finding a lover. The concept later evolved into use by both genders as a self-effacing badge of solidarity among those who felt hopelessly left behind by a nepotistic and materialistic society.

In 2011, the “Occupy Wall Street” movement broke out in the United States, wherein disgruntled millennials protested exploitative capitalism that had enabled vast wealth accumulation among the already wealthy. Always eager to highlight political dissatisfaction in Western countries, Chinese state media initially reported widely on the movement…until many Chinese began expressing sympathy with it. “China faces more serious problems of financial oligarchism, corruption, and inequality than America,” wrote one Chinese commentator. “But ‘Occupy Chang’an Jie’ [the street that runs through Tiananmen Square] is no more than a fairy tale — in China a jobless, homeless protester would not reach Beijing before disappearing mysteriously.”

China had come to embody the worst excesses of capitalism that Marx and the early Communist Party leaders had decried. Social trust had broken down, a vast underclass was caught in a cycle of economic exploitation, and a spiritual vacuum had sent people flocking to religion in search of meaning and guidance. The grand bargain of economic growth in exchange for political acquiescence was showing cracks, and the Communist Party feared social unrest ahead of its upcoming power transition in November of 2012. Some leaders with higher ambitions for that transition thought it was perhaps time for a revised model, and none was so bold in putting one forward as a charismatic party official in Chongqing.

New Left

In 2007, Bó Xīlái 薄熙来 gained a seat on China’s 25-person Politburo and was assigned to be party chief of Chongqing municipality and its nearly 30 million residents. While he was reportedly disappointed with the position at first, he ultimately decided it could be the perfect springboard to a seat on the all-powerful nine-man Politburo Standing Committee. Unlike the typical party official at this level, who tends to do well by keeping their cards close to their chest, Bo made little secret of his higher aspirations, and went all-in on populism.

The following year, Bo launched an neo-leftist campaign in the city ostensibly intended to revive Marxist ideals and bring about more equality in a city where the spoils of economic growth had disproportionately gone to a privileged few.

Many of the campaign’s initiatives appeared to do that. Subsidized low-income housing, improved healthcare and pensions, and more rights for rural migrants helped lift the poor. On the other end of the wealth gap, a sweeping crackdown on organized crime and corruption tore down the unjustly rich. But these policies weren’t enough. “A city’s development hinges on both physical and spiritual strength,” Bo said. “Only when we have a high morale and unite as one can we overcome all the difficulties.”

The campaign was supplemented with a Maoist revival. New statues of the long-dead dictator went up, “red” singing competitions were mandated, youth were encouraged to spend time in the countryside, and a propaganda blitz involving television, radio, newspapers, and text messages spread “revolutionary” slogans and themes that dated back to the Cultural Revolution.

To many foreign and domestic observers alike, a movement that harkened back to one of China’s most fanatical and violent periods seemed like a bizarre strategy. Many Chinese intellectuals warned of the danger, and skeptical students forced to participate in red events were quoted as saying they were just paying lip-service. But for a certain subset of young and old alike, the nostalgia for a supposedly simpler and more egalitarian time was appealing in an era of breakneck capitalism. Bo won grassroots supporters across the country, and in spite of his critics, he appeared to be wildly popular in Chongqing.

In the end, he was probably too popular. Bo’s charismatic rallying of public support independent of the Party hierarchy was anathema to the consensus-based backroom-deal-making that had become the norm in post-Mao China. It will never be known what the fate of Bo and his “Chongqing model” would have been absent the scandal that proved his undoing: a sensational defection attempt to the US consulate by his police chief that revealed Bo’s wife had been directly involved with the murder of a British national. But more moderate leaders including then-Party Secretary Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao undoubtedly saw Bo’s populism as a threat. In March of 2012, he was stripped of his positions, and the extent of his violent, law-breaking tactics used to seize assets and bring down enemies was revealed. He was later convicted and sentenced to life in prison for corruption and abuse of power.

Bo had amassed a personal fortune through his corruption, and his globe-trotting playboy son was the very embodiment of official privilege that many had come to despise. But Bo’s support among commoners — and the societal undercurrents that had fueled it — didn’t cease with his downfall. Far leftists across the country decried his purge as a politically motivated conspiracy, and some even called for the resignation of Wen Jiabao and Hu Jintao.

For others though, Bo’s fall represented hope that China might soon begin to liberalize. For years, Bo’s leftist Chongqing model had been held against the right-of-center Guangdong model. Put forth by that province’s party secretary Wāng Yáng 汪洋, a supposed rival for a seat on the Politburo Standing Committee, the model addressed China’s social ills with more government transparency, a greater role for civil society, and more rule of law. But it wasn’t to be.

Two movements that spooked the Party

Vice-President Xi Jinping — a then-unassuming bureaucrat about whom little was known by outsiders — was poised to take China’s top political position that November. In retrospect, it’s likely that Bo’s fall facilitated his rise to a level of power that few saw coming. But before Xi fully took the reigns, there would be two movements that exposed Party vulnerabilities from the left and the right, and likely shaped what was to come under Xi.

The first would be the largest mass demonstration since 1989, which once again began with Japan. In August of 2012, a long-standing territorial dispute over the uninhabited Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands reignited over the Japanese government plans to buy some of the islands from their private owners and nationalize them. Later that month, Hong Kong activists were intercepted and detained by the Japanese coast guard while trying to land on the islands.

On the weekend ahead of the September 18 anniversary of Japan’s invasion of Manchuria, anti-Japan demonstrations involving tens of thousands of protestors broke out — with government sanction — in more than 100 Chinese cities. Demonstrators carried anti-Japanese banners, pelted Japanese consulates with eggs and rocks, and went about destroying Japanese brand cars and businesses. But as they often had throughout the 20th century, these ostensibly anti-Japan protests began to illustrate problems closer to home.

Numerous stories would later emerge of young vandals that seemed not so much rabid anti-Japanese nationalists, but more atomized young men at the bottom of society who got swept up in the movement to feel a sense of purpose — sometimes becoming gratuitously violent in the process. Then there were the dozens of Mao Zedong posters hoisted at nearly every demonstration — some of their carriers asserting that, contrary to the current government, Mao would never let Japan get away with this. At one protest in Shenzhen, some were so bold as to unfurl a banner that read “Liberty, democracy, human rights and a constitution” and were promptly arrested. This time, the Communist Party wouldn’t let anti-Japan protests evolve into anything more. As quickly as they had begun, the protests were broken up by authorities and state media urged calm.

In November, Xi Jinping’s coronation went off without a hitch. Soon after, he appeared at “The Road Toward Renewal” exhibition at China’s national museum, which serves as an embodiment of China’s post-Tiananmen “National Humiliation” and “National Rejuvenation” narrative. The symbolism of Xi’s appearance was unmistakable, as was the implication of what he said there. “Nowadays, everyone is talking about the ‘China Dream,'” he said, using what would become his signature political slogan. “To realize the great renewal of the Chinese nation is the greatest dream for the Chinese nation.”

Xi had set the tone that he would be a staunchly nationalist leader. But almost as soon as he took power, he encountered the second movement — one that would likely fuel his eventual hardline authoritarian turn.

On New Year’s Day 2013, the liberal Guangdong newspaper Southern Weekly, which was known for its hard-hitting investigative reporting and frequent clashes with authorities, ran an editorial playing on Xi’s newly unveiled slogan titled “China’s Dream: The Dream of Constitutionalism.”

“Only if constitutionalism is realized and power effectively checked can citizens voice their criticisms of power loudly and confidently,” the editorial said. “And only then can every person believe in their hearts that they are free to live their own lives. Only then can we build a truly free and strong nation.”

Before the paper went to print, that gently critical social commentary was altered by a provincial propaganda official into an error-riddled homage to the Communist Party — and without forewarning to the paper’s editors. Upset by the particularly intrusive censorship, much of the paper’s staff went online to publicize what was happening and threatened to go on strike. What happened next surprised even the most seasoned China analysts.

Once news broke of the incident, countless people across the country rallied behind Southern Weekly. Celebrities with tens of millions of Weibo followers posted messages of support. “We don’t need the second highest GDP in the world, but we need a newspaper that speaks the truth,” wrote one prominent writer. “We don’t need a fleet of aircraft carriers, but we need a newspaper that speaks the truth.”

Meanwhile, thousands of ordinary people — particularly college students — uploaded photos of themselves holding signs with messages like “Let’s go Southern Weekly!” Perhaps most surprisingly, hundreds spontaneously showed up in-person outside the paper’s headquarters. As police circulated and photographed protestors in a bid to intimidate them, one young woman showed just how unfazed she and many of her peers were. As the officer drew his camera, she held up her fingers beside her face to form a “V for victory” sign.

Document 9

At the height of the Southern Weekly protests, the Central Propaganda Department sent an “urgent” internal notice to media outlets instructing that “Party control of the media is an unwavering basic principle” and that hostile foreign forces were behind the disturbance.

The ubiquitous, but curiously elusive and ill-defined “hostile foreign forces” had been whipping up trouble in China for decades. However, signals were emerging that people in very high places were taking their own propaganda seriously, and several events suggested they may have had reason to.

Between 2010 and 2012, China had discovered and dismantled — partly through executions — a CIA spy network operating in the country. And as the Arab Spring saw numerous Middle-Eastern dictatorships fall in 2011, overseas activist groups called for similar Jasmine Revolution-style protests in several Chinese cities. The protests amounted to very little — foreign journalists and other curious onlookers far outnumbered any Chinese protestors at most planned rendezvous points — but authorities were unmistakably spooked. Journalists were roughed up by police and ordered to delete video footage, dozens of Chinese participants were arrested, and the police presence ramped up dramatically in several cities.

At one of the planned protest sites in a crowded Beijing shopping district, U.S. Ambassador Jon Huntsman made a surprise appearance. The U.S. embassy later explained that it was coincidental, that he was just on a stroll with his family. But his presence nevertheless would be the subject of conspiratorial speculation for years to come, particularly after he left China later that year and entered the U.S. presidential race. “We should be reaching out to our allies and constituencies within China,” Huntsman said during a Republican primary debate that November. “They’re called the young people. They’re called the internet generation. There are 500 million internet users and 80 million bloggers, and they are bringing about change the likes of which is going to take China down.”

This Chinese “internet generation” wasn’t only being targeted by Western government provocateurs in the estimation of China’s leaders. They were also being corrupted by Western culture and values. In spite of a general disdain for the American government and foreign policy among young Chinese, Western movies, pop stars, products, and even concepts of individualism, personal liberty, and democracy were widely admired. For the Communist Party, this posed a danger, which became evident in late 2011 when its annual Central Committee plenum established an agenda for focusing on “cultural development” and protecting China’s “cultural security.” Soon after, Party Secretary Hu Jintao claimed that ideological and cultural fields were “the focal areas of [hostile foreign forces’] long-term infiltration” and that Western culture “is strong while we are weak.”

By 2013, between the long-standing fears of “peaceful evolution” by the West, the Jasmine Revolution, and the clear and present danger illustrated by the Southern Weekly protests, the need for drastic action had likely become abundantly clear. A month after Xi Jinping attained the presidency in March of 2013 and rounded out his power trifecta (along with heading the Party and military), an internal Party document was distributed to local officials across the country instructing them to prevent schools and media from discussing seven taboo topics that included “Western” constitutional democracy, universal values, civil society, neoliberalism, press freedom, historical nihilism, and questioning whether China’s system is truly socialist. After the release of Document 9, as the directive was called, everything changed.

In previous years, a certain level of dissent had been permitted in China. Activists like Liu Xiaobo who advocated a complete dismantling of the Communist Party’s absolute power had been locked away, but those with more modest hopes for reform had been spared the worst of the Party’s “stability maintenance.” That changed in 2013. In the aftermath of Document 9, constitutionalists, lawyers, feminists, labor leaders, NGOs, journalists, and generally anyone who raised their voice on anything at all was dealt with swiftly — often through lengthy prison sentences.

Online discourse was similarly reined in with more aggressive censorship and some high-profile arrests of major social media influencers. The once raucous Sina Weibo was, against most expectations, tamed. The Southern Weekly protests, which some had thought might signal the beginning of a free speech movement, instead marked the last large-scale spontaneous movement of the Weibo era. From that point on, the unrestrained internet movements and the large street demonstrations they occasionally yielded all but died out.

Universities, which had historically been hotbeds of political activism, were next in the crosshairs. Several politically outspoken professors were censured or fired in the months and years following Document 9. In early 2015, China’s education minister reportedly told university officials to disallow teaching materials that “disseminate Western values,” and by the end of 2016, the ideological direction universities were being pushed in was formalized at a high-level education conference.

Speaking at the conference in front of several other Standing Committee members and top military, propaganda, and education officials, Xi ordered universities to ramp up their ideological work. But in the war against “Western values,” there were only so many ideological weapons in the Party’s arsenal. So Xi doubled down. “We must adhere to the guidance of Marxism,” he said. “Build colleges into strongholds that adhere to Party leadership.”

Within months, “ideological inspections” were carried out at dozens of top universities. Schools scrambled to establish centers for the study of “Xi Jinping Thought.” And the already heavy load of political courses students were subjected to was bolstered. Meanwhile, Xi was becoming even more powerful. At the 19th Party Congress in late 2017, he all but secured himself an unlimited tenure as China’s top leader and joined the likes of Mao and Deng by enshrining his personal doctrine in China’s Constitution, known as “Xi Jinping thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era.”

Rounding up the Marxists

But while authorities were so nervously on the lookout for ideological threats from the right, they got crept up on from the left.

For years, there had been warning signs that forms of socialism other than what’s offered by the Communist Party might be gaining appeal among a certain subset of Chinese. If Bo Xilai’s popularity and the ubiquitous Mao posters at the anti-Japan protests weren’t enough, leftist websites and chat rooms had been attracting thousands. In 2014, a few dozen beleaguered college graduates even banded together to form a Maoist-style commune in rural Hebei. Still, the sudden emergence of ardent Marxist student activists in cities across China appeared to surprise everyone.

It began at PKU in early 2018 when a group of students — emboldened by the global #MeToo movement — began demanding information related to the 1998 suicide of a student who had allegedly been raped by a professor. Self-professed Marxist students at the school had previously initiated campaigns aiming to help migrant service workers at the university and aid rural families. But their move into women’s rights brought them into the international spotlight.

When PKU inevitably began to suppress the small movement through threats towards ringleaders, more students at the university joined in and thousands rallied to their support online. Big character posters invoking the May 4 Movement were spotted around the university, criticizing university administrators over their handling of the matter.

By mid-summer, many of the same students took on another cause near and dear to Marxists’ hearts: workers’ rights. At the Jasic machinery factory in Shenzhen, workers disgruntled by poor treatment and low pay tried forming a labor union to protest the company. In response, several organizers were fired, and later, after weeks of protests, dozens were detained. Then, in a shocking display of cross-class collaboration scarcely seen since 1989, dozens of Marxist students and recent graduates from across the country traveled to Shenzhen to protest on the workers’ behalf.

In some ways, this union may have been even more worrying to authorities than that between workers and students in 1989. During the Tiananmen Movement, students were at times openly disdainful of workers — even preventing them from speaking at rallies. The marriage born amid the spontaneous mass movement was one of convenience more than genuine sympathy. But at Jasic, students appeared motivated by genuine concern for workers’ rights. As with the Southern Weekly protests and many other social movements that had developed prior to Xi’s crackdown, young activists with a social conscious pushed for lofty ideals not necessarily tied to their own immediate interests.

But unlike with the Southern Weekend protests, the young activists asserted that their interests and those of the Communist Party were the same. In a bold open letter to Xi Jinping himself, one of the most prominent student leaders, recent PKU graduate Yuè xīn 岳昕, wrote that her activities and those of the workers were in line with China’s constitution, and that she had actually been inspired by Xi’s speech at Peking University earlier in the year.

“As a young person who grew up in socialist New China, a youth who lives in the New Era, I have no excuse to stand by and do nothing, to look on helplessly as the workers of Shenzhen struggle alone,” Yue wrote. “We learn in middle school history books how the May 4th Movement was an extremely important event in China’s modern contemporary history. It was an anti-imperialist, anti-feudalistic patriotic movement, the beginning of China’s new democratic revolution; it led to the birth and development of the Chinese Communist Party.”

Much like CCP founder Chen Duxiu and other early socialists at PKU, Yue’s brand of Marxism was a purer one that didn’t preclude individual liberties and a strong rule of law. In middle school, she had reportedly cut her teeth on texts like Liu Yu’s Details of Democracy and reform advocate Zhang Qianfan’s The Constitution of China. In high school, she was inspired to activism by the 2013 Southern Weekly movement. “The impact [of the protests] on me was very big,” she recounted in an interview. “After that incident, I knew that the public opinion of the news was oppressed. I felt that I should do journalistic work and make a positive impact on the political environment.”

Whether she was being tactical or simply naïve in claiming to be inspired by Xi Jinping and the modern Communist Party, she had hinted that the CCP wasn’t quite living up to its own ideological ideals. “Marxist theory is a mandatory course in China,” she said in one online post. “But if you want to learn original Marxism, you need to read on your own.”

Authorities predictably had little sympathy for Yue’s position. By September, she had been detained, but not before exposing the ideological schism that stretches back a century.

Uninterested in challenging Yue and her peers on any ideological basis, authorities once again fell back on their fundamental source of power: raw coercion. They went about rounding up Marxists by the dozen — sometimes violently — and dismantling student groups devoted to the ideology across the country. Nevertheless, many students continued their activism, started campaigns to find their missing peers, and attracted new sympathetic supporters. Well into the winter, The Peking University Marxist Student Association was holding nightly runs around the university’s May 4 running track, shouting slogans supporting the working class and singing “The Internationale.”

Months later, video “confessions” depicting several student leaders including Yue Xin were screened for remaining rabble-rousers. What exactly happened to those youths while in detention remains unknown, but their defiant and idealistic stance had unmistakably been broken. In her purported confession, Yue apologized for breaking the law. “I will read the ideological and historical books that are produced by the Party,” she reportedly said. “Now I understand that it is only the Communist Party of China that can be concerned about the rights of workers and peasants in the New Era.”

Like other small youth movements that have emerged among this young “internet generation” in recent years, this one now appears to have been suppressed into a smolder, leaving the question: is the Party firmly in control, or could one of any number of smoldering movements have the potential to spark a fire that the Party loses control of?

May 4, 2019

On the upcoming anniversary of the May 4 Movement, the Communist Party will undoubtedly use the occasion to celebrate itself as the descendent of the youthful idealism and political furor that grew out of Peking University 100 years ago: here is one such piece of propaganda in which Xi Jinping exhorts “country’s young people to be patriotic and strive for the bright prospect of national rejuvenation.” Less likely to be celebrated is the complexity of the man who co-founded the Party and ultimately rejected the ideological path it took. And almost certain to go unmentioned one month later will be the 30th anniversary of the movement inspired by May 4 that was brought to a bloody end in 1989.

Party doctrine continues to zealously guide which lessons are allowed to be gleaned from history: Be thankful for the Party that Chen Duxiu founded, but don’t look too closely at his actual views. Study Marxism, but only within the parameters we set. Champion China’s “democracy,” but don’t question the validity of how we define it. Celebrate the May 4 youth movement, but don’t dare replicate it.

Whether China’s young will continue to stick to those scripts is no longer much of a question — many are already challenging them — but whether or not it will ever again pose an existential threat to the Party’s monopoly on power is still up for debate. Mass movements have historically been fickle events in China — impossible to predict in terms of how they’ll begin and how they’ll ultimately resolve. But the Party is clearly concerned.

In January, following the release of economic data showing that China grew in 2018 by its slowest pace in nearly three decades, Xi Jinping warned a gathering of high-level officials to be on guard against black swan events that could threaten the Party’s “political security.” But it wasn’t exactly the economy that seemed to most concern him. “Now the main front of the ideological struggle is on the internet, and the main audience of the internet is young people,” he said. “Many domestic and foreign forces are trying to develop supporters of their values and even to cultivate opponents of the government.”

The grievances that fueled the internet-driven protest movements early in this decade have have been mostly pushed beneath the surface, but far from resolved — many have in fact festered and become much worse in the time since. And hanging over everything is an unbalanced, debt-ridden economy that appears more vulnerable than it has been since reforms began. A generation that was brought up never experiencing anything but a stable and fast-growing economy is now facing numerous socioeconomic challenges that are already proving highly disruptive to the lives many hoped for and expected. At the same time, in just the past decade, legions of Chinese youth have illustrated a willingness — excitement even — to take to the streets on behalf of causes greater than themselves and at odds with the Party’s agenda.

To boot, the Communist Party has yet to meaningfully fill the ideological void leftover from when it embraced capitalism. It continues to tout Marxism while practicing Leninist authoritarianism and suppressing those who highlight the gap between the two.

So far, the insistence on blind obedience to the Party, and swift repression of those who reject it, has worked. The economy, while harboring major cracks, likewise remains good enough to sustain widespread support for one-party rule. And major conditions that facilitated the Tiananmen Movement — most notably, a high-level leadership split that allowed information to spread, subversive narratives to proliferate, and protests to grow unfettered — don’t appear likely in the immediate future. But to assume this trend can continue indefinitely while bringing ever-more people face-to-face with with the increasingly repressive tactics of the state would be foolhardy.

Predicting if and when the Communist Party will experience a serious challenge to its authority has made fools of many analysts over the decades. It has weathered unmitigated catastrophes without experiencing significant opposition, only to later see mass demonstrations materialize from surprise events while things appeared tranquil. Youth movements have a way of remaining absent when expected, and suddenly emerging when they’re not.

What comes after a youth movement is even more unpredictable. They sometimes spark positive change, but often only see the situation revert back to the status quo, or yield an even more iron-fisted set of rulers.

“Patriotism is an ideal tool to extort from and oppress the people”

Much of China (and the outside world for that matter) agrees that the country is at the dawn of a “New Era.” But what will mark that era is very much up for interpretation: Will it be the era of triumph and pride as touted by Xi? One of tough but manageable muddling through? Or will it be something far bleaker than those scenarios — a continuation of the cycle of hardship, violent ideological struggle, external conflict, repression, and rebellion that’s been difficult to shake for most of China’s past two centuries?

The answer to that question may well be answered by the country’s youth. Throughout modern history, for better or worse, they’ve been the vanguard for much of China’s most tumultuous changes — something far from lost on a century’s worth of elder leaders.

One-hundred years after Chen Duxiu laid the groundwork for China’s Communist Party, the man who now heads it could hardly be at greater odds with its founder when it comes to what the role of these youth should be. Since taking power, Xi has draped himself in the banner of patriotism and sought to conflate love of country with love of Party. With a seemingly increasing sense of urgency, he has insisted that the young to be collectivist, patriotic, and above all, obedient to the Party’s dictates.

Xi gave a speech on Tuesday at the Great Hall of the People to commemorate the May 4 anniversary to an audience of students, workers, soldiers, and the entire Politburo Standing Committee. He called on the young to learn from the spirit of the May 4 Movement, which he said centered on “patriotism, progress, democracy, and science…with patriotism as its core.”

But perhaps cognizant of the potential for other lessons to be drawn from the spontaneous mass movement a century ago, he noted that in the “New Era,” the theme and direction of Chinese youth movements and the mission of Chinese young people must be to uphold the leadership of the Communist Party.

“It is very shameful if a person isn’t patriotic, or even deceives or betrays the motherland,” Xi declared. “In contemporary China, the essence of patriotism is to combine one’s love for the country with love for the Party and socialism.”

“Chinese youth in the New Era must obey the Party and follow the Party.”

Chen Duxiu, however, viewed youth as a “newly sharpened blade” meant to eliminate the old and rotten, and asserted that “there is definitely no reason why one should blindly follow others.”

In his 1915 essay “Call to Youth,” he exhorted the young to “be independent, not submissive,” “progressive, not conservative,” “outspoken, not reserved,” and “cosmopolitan, not parochial.”

By June 1919, with the ashes of World War I still smoldering, and one month after the May 4 Movement had seen students self-identifying as patriotic being repressed by a government also self-identifying as patriotic, Chen called into question the very idea of patriotism.

“Patriotism! Patriotism!” he wrote. “This sort of clamor in recent years has nearly stuffed the society of our country full. It is corrupt, useless officials and barbaric soldiers who in speech often hang the banner of patriotism.”

“Patriotism is an ideal tool to extort from and oppress the people,” added the man who would two years later co-found the Communist Party. “What we love is a country where the people use patriotism to resist oppression, not a country that uses patriotism to oppress.”