Tiananmen Square 30 years on: 30 essential stories about June 4, 1989

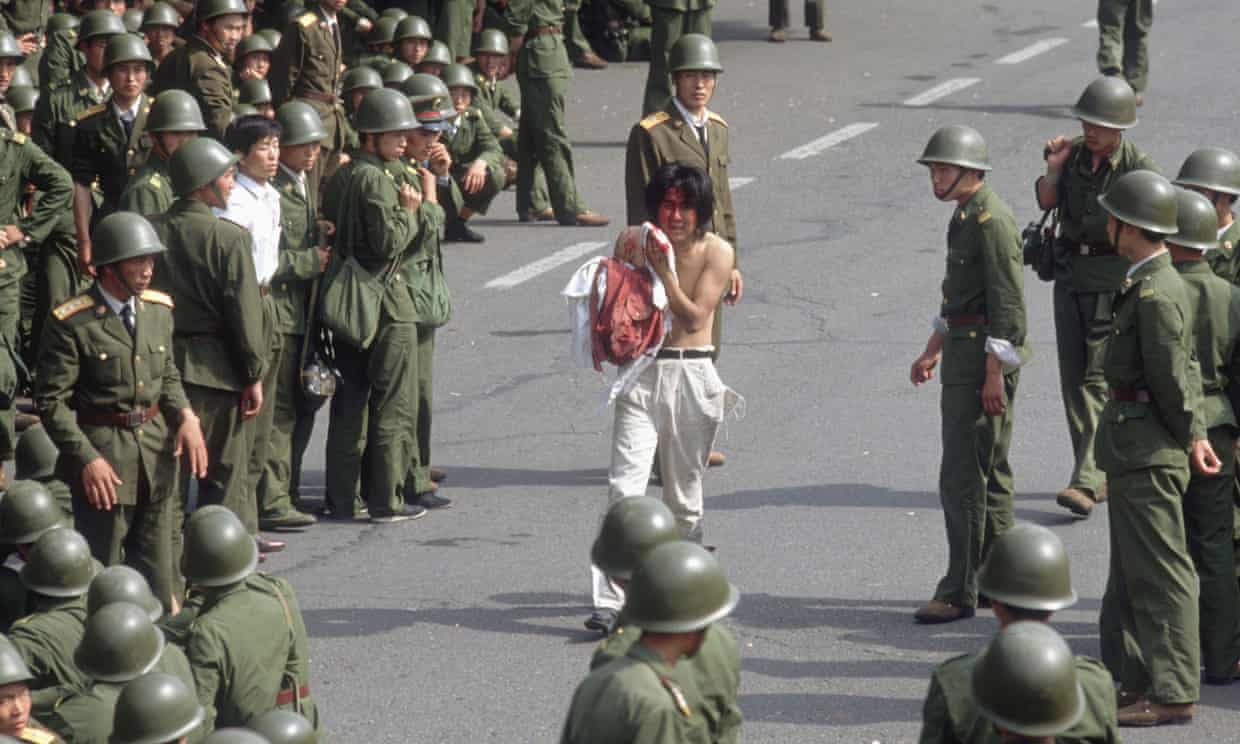

Photo by Jeff Widener, June 5, 1989

On the night of June 3, 1989, China invaded its own capital with tanks and soldiers, and by the following morning had successfully crushed a monthlong protest that top leaders believed threatened the survival of the Communist Party. The decision to use deadly force revealed a deep insecurity within the Party, one that has arguably intensified as the years have rolled on, even as the country has inarguably grown stronger in other measurable categories. Today’s date, June 4, has become a permanent stain in the history of a country that keenly appreciates narrative, particularly its own. It is a source of consternation, heartache, embarrassment, mourning, and rage — and the harder the Communist Party tries to efface it, the more nacreous it becomes, an enduring reminder of a calculated mistake.

And so, on this 30th anniversary of June Fourth, our commemoration takes the form of a selection of pieces published in the past 30 years — from firsthand and contemporary accounts of the protests and bloodshed, to analysis of Communist Party documents illuminating what led to the decision to use deadly force, to poetry and multimedia resources and essays — that make the monumental events of 1989 feel personal and fresh to this day.

A quick note about the selection process: I made a concerted effort to pick stories from years past worth a revisit, though I admit to a bit of recency bias. The list isn’t meant to be definitive, but I trust you’ll find many stories here that deserve your time.

Crackdown in Beijing; Troops Attack and Crush Beijing Protest; Thousands Fight Back, Scores are Killed

By Nicholas Kristof

The New York Times, June 4, 1989

Nicholas Kristof, who was the Beijing bureau chief for the New York Times in 1989, would go on to share the Pulitzer Prize for international reporting with his wife, Sheryl WuDunn, for their coverage of the crackdown. You won’t find a much better series of real-time on-the-ground reporting than this; as the Pulitzer jury in 1990 put it: “They got it right.” The New York Times has helpfully collected Kristof and WuDunn’s stories on this page. (The two would co-author China Wakes: The Struggle for the Soul of a Rising Power.)

In a column published this past Saturday, Kristof recounts: “I particularly recall one burly rickshaw driver. He had a couple of bleeding people on the back of his cart and was pedaling furiously, his legs straining. He saw me and swerved toward me so that I could bear witness to his government’s brutality. As he passed, he pleaded with me: Tell the world!”

Also see:

- China Erupts…The Reasons Why, by Nicholas Kristof, The New York Times, June 4, 1989

- Tiananmen: The story as it was written 25 years ago, by John Pomfret (who adds more details about his experience reporting on Tiananmen in his book Chinese Lessons), Associated Press, June 4, 1989

The Gate of Heavenly Peace

Produced by Richard Gordon and Carma Hinton, Long Bow Group

Written by Geremie Barmé and John Crowley

1995

Simply put, the best film about the protests and the violence that ensued. The filmmakers sifted through more than 300 hours of footage over five years to produce this riveting three-hour documentary. Events are placed in historical context and examined through a Chinese lens. There are interviews with Liu Xiaobo 刘晓波, Han Dongfang 韩东方, Wuer Kaixi 吾尔开希, Chai Ling 柴玲, Wang Dan 王丹, and more.

Also see: The Gate of Darkness, by Geremie Barmé, China Heritage, June 4, 2017 (updated May 31, 2019) — A heavyweight in the China-watching business, Barmé never pulls punches: “Even with the passage of time — and despite the sophistry applied by hacks of all sorts to excuse mass murder in the streets of the Chinese capital — the Fourth of June, the ‘Tiananmen Square Incident’, or as I have always called it, the Beijing Massacre, shames China as well as the fellow travellers of the Chinese Communist Party. No matter how the barbarism is justified, it beclouds still that country’s collective conscience.”

The Tiananmen Papers

Introduced by Andrew J. Nathan

Foreign Affairs, January/February 2001

In 2001, hundreds of internal Communist Party documents from 1989, which had been secretly smuggled out of the country, were collected and published by PublicAffairs under the title The Tiananmen Papers. While it’s difficult to verify the authenticity of the documents — China has called them fake — the editors stand by the credibility of their source, whose identity remains protected to this day. If authentic, these papers are monumental, revealing the thought process that led top leaders, who were genuinely fearful of the Party’s survival, to authorize the use of deadly force on civilians.

The link above is an introduction written by Andrew J. Nathan, one of the three editors/translators (along with Perry Link and Orville Schell). It’s lengthy, but also one of the best reads for understanding exactly what happened. Here’s an excerpt of an alleged conversation, from May 13, 1989, between Party General Secretary Zhao Ziyang and senior leader Deng Xiaoping:

Zhao Ziyang: … I’ve noticed that this movement has two particular features we need to pay attention to: First, the student slogans all support the Constitution; they favor democracy and oppose corruption. These demands are basically in line with what the Party and government advocate, so we cannot reject them out of hand. Second, the number of demonstrators and supporters is enormous, and they include people from all parts of society. So I think we have to keep an eye on the majority and give approval to the mainstream view of the majority if we want to calm this thing down.

Deng Xiaoping: It was obvious from the start that a tiny minority was stirring up the majority, fanning the emotions of the great majority.

Zhao Ziyang: That’s why I think we have to separate the broad masses of students and their supporters from the tiny minority [who are] using the movement to fish in troubled waters, stir up trouble, and attack the Party and socialism. We have to rely on guidance. We have to pursue multilevel, multichannel dialogue, get in touch with people, and build understanding. We mustn’t let the conflicts get nasty if we expect things to settle down quickly.

Deng Xiaoping: Dialogue is fine, but the point is to solve the problem. We can’t be led around by the nose. This movement’s dragged on too long, almost a month now. The senior comrades are getting worried. … We have to be decisive. I’ve said over and over that we need stability if we re going to develop. How can we progress if things are in an utter mess?

The Impact of Tiananmen on China’s Foreign Policy

By Harry Harding

The National Bureau of Asian Research, December 1, 1990

A bit of instant analysis of where China stood less than a year after the crackdown. Interesting to compare China’s trajectory with where it ended up.

The basic tone of Chinese foreign policy between the fall of 1989 and the spring of 1990 was set not by the hard-liners, but rather by the tough internationalists. They insisted that China’s strategic and economic importance, together with the gradual restoration of internal stability, would force foreign countries to restore relations with China.

Also see: The Legacy of Tiananmen for Chinese Politics, by Susan Shirk, Huffington Post, July 4, 2009

China After Tiananmen: Money, Yes; Ideas, No

By Perry Link

The New York Review of Books, March 31, 2014

Adapted from Perry Link’s foreword for Rowena Xiaoqing He’s book Tiananmen Exiles: Voices of the Struggle for Democracy in China. Link, who is banned from mainland China for co-translating The Tiananmen Papers, writes about how the Party used money and the pursuit of wealth to replace the legitimacy it lost, and how this has created a “poverty in the society’s public values.”

Very few people risk principled objection in public. The regime calls this “dissidence,” and the costs of dissidence are high. People find it smarter to lie low, perhaps fulminating in private but not rocking any boats in public. Dissidents are viewed, even sometimes by their own families, as somewhat odd, and as poor calculators of their own best interests. Friends and neighbors keep them at a distance — far less because they disagree with their ideas (as the regime likes to claim), but out of fear of absorbing their taint. When Wang Dan went to visit his father’s hometown after he became known as a dissident, people guarded the entrances to their villages to make sure he didn’t come too near.

Some Chinese accept the regime’s lies while others only pretend to, but with passing time this distinction becomes less and less important. In either case people’s self-interest is protected and they fit into “normal” society. In the end, as Rowena He puts it in Tiananmen Exiles: Voices of the Struggle for Democracy in China, China is left with “a generation that cannot even imagine a society whose youth would sacrifice themselves for ideals.”

Also see: China continues to deny Tiananmen, but we won’t let the world forget, by Rowena Xiaoqing He, The Guardian, June 3, 2019

Tiananmen’s Wake

By Pankaj Mishra

The New Yorker, June 23, 2008

A review of Ma Jian’s novel Beijing Coma, whose narrator is shot during the 1989 crackdown. Ma Jian himself participated in the demonstrations, and now writes in exile. Mishra, in his review, writes:

“The struggle of man against power,” Milan Kundera once wrote against a similar backdrop of Communist indoctrination, “is the struggle of memory against forgetting”; and, at nearly six hundred closely printed pages, “Beijing Coma” seems determined to enshrine the strivings of “the Tiananmen Generation.”

The Great Tiananmen Taboo

By Ma Jian

The Guardian, June 2, 2009

A moving personal essay by Ma Jian. Here’s an excerpt where he visits with a soldier who participated in the crackdown:

I’d never heard a soldier give a first-hand account of the crackdown. He took a deep drag from his cigarette and continued, his eyes beginning to redden: “Each soldier was given a loaded rifle and told to stand in line. Most of us were young boys from the villages. We had hardly eaten for days. We were weak and terrified, convinced we were going die. Some guys shat themselves, others were trembling so much that they inadvertently fired their guns and injured fellow soldiers.

“At 12 midnight on 4 June the doors of the Great Hall were swung open. It was chaos outside. Special forces in camouflage were brandishing bayonets and driving out the students still left in the square. Nearby, a small group kicked a student to the ground and hit his skull with their rifle butts. I heard machine-gun fire in the distance, and saw the Goddess of Democracy being rammed by a tank and topple to the ground …”

Also:

This spectacular night scene of the mass hunger strike in Tiananmen Square 1989 was taken by a friend of mine. He wants it to be shared, but is too afraid to reveal his name. pic.twitter.com/dlemRXY3l4

— 马建 Ma Jian (@majian53) June 4, 2019

Children of Tiananmen

By Orville Schell

Rolling Stone, December 14, 1989

Schell, one of the foremost foreign scholars of China, profiles Wuer Kaixi and Shen Tong 沈彤, two young leaders of China’s pro-democracy movement.

Although the people in the crowd were clearly touched by what Shen was telling them, there was also some confusion. Filled with outrage over the murders they had seen carried out on television, they wanted an outlet — some ritual of condemnation and retaliation. They were not quite prepared for this casually dressed young man floating up before them to speak not of revenge but of self-cultivation and love.

Also see: Hero of Tiananmen Square, by Orville Schell, Granta, March 1, 1994

Enemy of the State

By Jianying Zha

The New Yorker, April 16, 2007 (for the April 23, 2007 issue)

Jianying Zha has a special ability to take readers into the hearts and minds of her subjects, whether it’s her brother, Zha Jianguo, a democracy activist who she profiles in the above article, or those who work within the state apparatus.

I was living in Beijing at the time and visited the square daily. Jianguo said little when we met, though he was evidently in turmoil. One afternoon, I asked him to join me while I visited a friend who was active in the protests. Outside on the square, my friend greeted me warmly and invited me to come inside the tent where a group of student leaders were meeting, but when Jianguo followed me he frowned and barred him: “No, not you!” I explained that the man was my brother. My friend looked incredulous. Here, in his native city, Jianguo stood out as a country bumpkin. And, in 1989, the democracy activists were members of an urban élite. My friend’s snobbery must have driven home the message to Jianguo: Stand aside. This is not your revolution.

Soon, it was nobody’s revolution. What happened to the Tiananmen protesters on June 4th showed what awaited those who openly challenged the system.

China’s Dictators at Work: The Secret Story

By Jonathan Minsky

The New York Review of Books, June 3, 2009

A review of Zhao Ziyang’s posthumous memoir, Prisoner of the State. Zhao was China’s premier in 1989, a reformer who attempted to rally the country’s leadership around a conciliatory line toward the protesters. Later, he appealed directly to the protesters on the square, telling them, “I came too late.” He was punished for his efforts, and died under house arrest in 2005.

Zhao’s memoir brings home a devastating realization: how a series of events had to go wrong for Deng Xiaoping to turn to his military, and exactly how that series of events went wrong.

Also see: China’s ‘Black Week-end’, by Ian Johnson, The New York Review of Books, May 31, 2019 (for the June 27, 2019 issue): A review of The Last Secret: The Final Documents from the June Fourth Crackdown, a book published in Hong Kong, edited by Bao Pu, that details the meeting of about 30 senior leaders in mid-June 1989 in which Deng sought “to force other party leaders to retroactively endorse his decision to use force on the protesters and to fire the Communist Party’s general secretary, Zhao Ziyang, who had opposed using the military to stop the demonstrations.”

Tiananmen at Twenty-Five: “Victory Over Memory”

By Evan Osnos

The New Yorker, June 3, 2014

An essay about the lengths the Chinese government has gone — and will go — to enforce forgetfulness on its populace.

Forgetting can be an act of will, but so can remembering. By staying silent on the events of Tiananmen Square instead of making a case that it was a mistake in the rise of a nation, Party leaders have not succeeded in effacing it from history. They have simply ceded the subject to their opponents, and, year by year, Tiananmen is discovered and rediscovered by young people, for whom it is a stark measure of the gap between China’s official and unofficial histories.

The Ghosts of Tiananmen Square

By Ian Johnson

The New York Review of Books, June 5, 2014 (paywalled, but available in full on ChinaFile)

“Remembering can raise unpleasant questions.”

A review of two books, Louisa Lim’s The People’s Republic of Amnesia and Rowena He’s Tiananmen Exiles.

China wants us to forget the horrors of Tiananmen as it rewrites its history

By Louisa Lim and Ilaria Maria Sala

The Guardian, May 19, 2019

“Remembering the deaths of 4 June 1989 is no neutral task,” the authors write. “It is a civic duty, a burden and an act of resistance in countering a state-level lie that risks spreading far beyond China’s borders.” Lim and Maria Sala should know: the former wrote a book on the subject, while the latter was on the square during the protests, and has collected her photos in a forthcoming book, Pechino, 1989.

Also see: On China’s State-Sponsored Amnesia, by Yan Lianke, The New York Times, April 1, 2013

Sensitive Words 24th Anniversary of Tiananmen

China Digital Times, June 3, 2013

A list that gets updated every year, with terms such as “63+1,” “tank,” “-ism,” and more. I’ve chosen the 2013 edition to link here because of the Zhuangzi quote, but also of note is the 2016 list, i.e., five years of sensitive words.

Also see: How China has censored words relating to the Tiananmen Square anniversary, by Kuang Keng Kuek Ser, PRI, June 4, 2016

Four Is Forbidden

By Yangyang Cheng

ChinaFile, May 30, 2019

Yangyang Cheng, who writes The China Project’s Science and China Column, in a poignant personal essay about how she came to learn the truth about Tiananmen.

Sometimes, the only power of a taboo is fear itself.

What Bob Hawke’s powerful Tiananmen Square speech reveals about his foreign policy

By Philip Williams

Australian ABC News, May 18, 2019

Australia’s prime minister at the time of the crackdown, Bob Hawke spoke passionately and tearfully about the June Fourth victims at a memorial service in Canberra on June 9, 1989. “It was the rawest of emotions ever on public display by an Australian prime minister, past or present,” the Australian ABC notes in the article above (where you can watch Hawke’s speech). He unilaterally offered asylum to thousands of Chinese nationals by extending their visas. When told, “You cannot do that, prime minister,” he replied, “I just did it, it is done.”

“It broke my heart for China,” Hawke said in a later interview.

Also see: Hawke ‘sparked movement’ after Tiananmen, by Kathryn Bermingham, The Canberra Times, June 4, 2019

China’s other Tiananmens: 30 years on

By Lily Kuo

The Guardian, June 2, 2019

Remembering the 1989 demonstrations in hundreds of other Chinese cities, including a bloody suppression of protesters in Chengdu:

Between April and early June 1989, the south-western Chinese city had been overtaken by students protesting in solidarity with their peers in Tiananmen Square in Beijing. In the early hours of 4 June, those students were shot or crushed by tanks as the military cleared the square. In Chengdu, enraged students and citizens poured on to the streets, demanding “blood for blood”. Following Beijing’s lead, the city’s security forces were deployed.

‘June Fourth’ Seventeen Years Later: How I Kept a Promise

By Pu Zhiqiang

The New York Review of Books, August 10, 2006 (non-paywall: ChinaFile)

Pu Zhiqiang is a civil rights lawyer who has served time for helping Tiananmen dissidents. Here, he writes about his guilt over “forgetting.”

If I just slouch along through life, taking the easy route, what do I say to the spirits of those murdered “rioters” of seventeen years ago? And if everyone forgets, are we not opening the door to future massacres? Our Tiananmen generation is now in middle age; we are in positions where we can make a difference. Do we not want to?

Remembering Tiananmen Square

By Robin Munro

The Nation, June 2, 2009

One of the final foreigners to leave the square as the army descended, Munro details all that he saw amid a long night of violence and chaos.

At about 9 A.M. on Sunday, June 4, several foreign witnesses, inspecting the devastation of the previous night, were stunned to see a column of some three dozen A.P.C.s suddenly appear from the west and come to a halt at the Muxidi intersection. The first vehicle had struck the remnants of a barricade; a second had run into its rear, bringing the convoy to a halt. A large crowd materialized from the neighboring alleyways and surrounded the now silent armored column. The first troops to emerge were beaten, and at least one is thought to have been killed. Only the intervention of student pickets, who negotiated safe passage for the troops, headed off a pitched battle and, perhaps, a fresh round of killing. Several hundred soldiers simply walked away, leaving behind their lethal hardware for the crowd to muse over. Within half an hour, all the A.P.C.s had been set on fire, and a towering column of black smoke could be seen for miles.

The unlikely confluence of events that led to the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests

By Kaiser Kuo

The China Project, June 4, 2018

Initially, the protests were not couched directly in terms of “democracy.” And the protesters made no effort whatsoever, at first, to include other segments of Beijing society. They were adamant about this. As they marched past Xisi, where I was staying with my grandmother and my college roommate who had by chance arrived from California on the very day that Hu [Yaobang] died, I hurried out from the alley to the main north-south street and watched as they marched toward the Square. The marchers on the periphery of the parade held pink colored packaging twine that circumscribed the marchers. It was meant to exclude anyone else.

Also see: No, 10,000 Were Not Killed In China’s 1989 Tiananmen Crackdown, by Anthony Tao (me), The China Project, December 25, 2017 — “The Tiananmen tragedy — call it a massacre if you’d prefer, I won’t object — remains a blight on the collective Chinese psyche…It doesn’t matter whether 100 or 3,000 people were killed, the consequences live on to this day, and millions have been impacted. We don’t need ‘10,000 killed in Tiananmen’ obfuscating this truth.”

The road not taken: China after Tiananmen

By James Kynge

Financial Times, May 24, 2019

Kynge, who covered the Tiananmen protests for Reuters, goes in search of the activists he met in 1989.

When dissidents arrive in exile, a flurry of excitement greets them. But as time passes they often fall victim to a groundhog day dynamic; every year around the Tiananmen anniversary the same people are asked the same questions by the same journalists and, eventually, the public gets bored.

Tiananmen, Inc.

By Ian Buruma

The New Yorker, May 23, 1999

A look, a decade later, at some of the protesters, including Chai Ling, “the most visible leader of the Chinese student rebellion,” who fled to the U.S. and enrolled in Harvard Business School.

Thoughts on River Elegy, June 1988-June 2011

By David Moser

The China Beat, July 14, 2011

River Elegy was a six-part documentary that aired on CCTV in 1988. It is iconoclastic, daring to attack symbols of Chinese civilization itself, such as the Yellow River and Great Wall. After the protests in 1989, it was removed from airwaves, and has rarely been seen since.

Poems for Tiananmen by Liu Xia and Liao Yiwu

Asian American Writers’ Workshop, June 4, 2014

Liu Xia, the widow of Liu Xiaobo, wrote the poem “Dark Night” in 1997. It begins (translation by Ming Di and Jennifer Stern):

Eyes will return tonight

with their ghosts

in the shape of tombstones.

Author Liao Yiwu wrote the poem “Massacre” (translated by Wenguang Huang) on June 4, 1989. He was sentenced to four years in prison as a result.

See more of Liao’s writing here.

The Last Gunshot: The musical legacy of the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre

By Elson Tong

Hong Kong Free Press, June 4, 2016

A selection of songs related to the protests, including Cui Jian’s 崔健 “Nothing to My Name” (一无所有 yīwúsuǒyǒu), which was the unofficial anthem of the student protesters. Many of these are sung at the annual June 4 Victoria Park candlelight vigil in Hong Kong, which HKFP notes “has the format of a well-rehearsed concert.”

Also see: Who owns “Bloodstained Glory,” the dissidents or the patriots? by Jemima Baar, The China Project, March 2, 2018 — “Bloodstained Glory” was originally written to commemorate Chinese soldiers who died in the Sino-Vietnamese War, but Anita Mui’s version is now sung every year at Victoria Park.

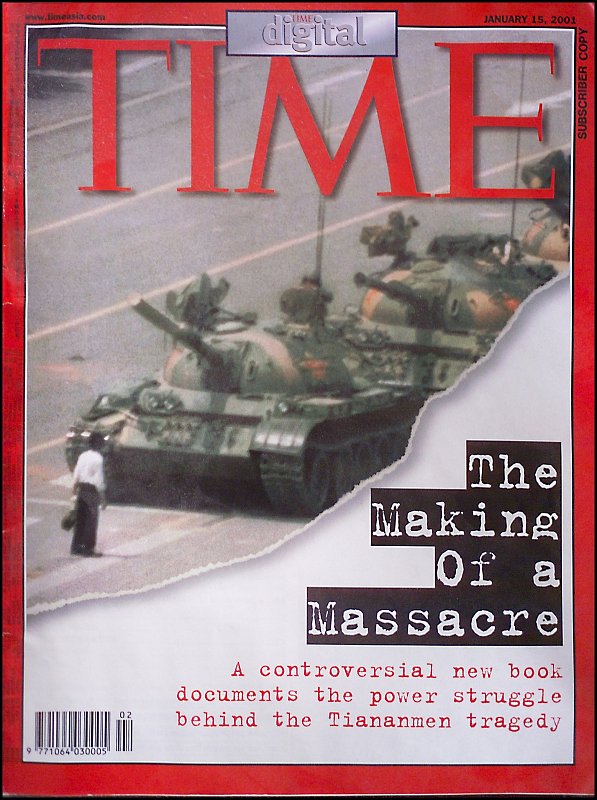

Tank Man

By Jeff Widener

The man who took the iconic Tank Man photo, which would appear on the cover of Time Magazine, recounts how he did it:

Our security man was between floors arguing with a colleague so we got inside the elevator and headed for the roof. Once there, I instructed Kirk to hide my film in his underwear because I figured if we were caught, they would probably check me first since I had a camera and Kirk was only wearing a T-shirt and shorts. To my surprise, a young western couple was sitting on the edge of the roof with their legs dangling. I told them it was unsafe because a sniper could pick them off and they also brought attention to Kirk and me. The two ignored us and kept swinging their legs. In the hazy distance, I could see dozens of tanks and support vehicles, but the scene was too far away even for a 400mm lens.

Also see:

- Behind the Scenes: Tank Man of Tiananmen, by Patrick Witty, The New York Times, June 3, 2009

- 30 Years After Tiananmen, ‘Tank Man’ Remains an Icon and a Mystery, by Javier C. Hernández, The New York Times, June 3, 2019

Tiananmen Square, 1989: The Declassified History

Edited by Jeffrey T. Richelson and Michael L. Evans

National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 16, June 1, 1999

Declassified U.S. government accounts of the events in Beijing in June 1989. Among the notable documents is No. 31, sent on June 22, 1989, in which the authors attempt to “set the record straight”:

Contrary to earlier reports in the western media, the cable asserts that many if not most of the deaths associated with the crackdown occurred on Changan Avenue and other streets surrounding the square, rather than on Tiananmen Square itself. The document calls the notion that the military could have suffered more casualties than civilians “inconceivable,” but holds that “civilian deaths probably did not reach the figure of 3,000 used in some press reports,” but believes that the figure put forward by the Chinese Red Cross of 2,600 military and civilian deaths with 7,000 wounded to be “not an unreasonable estimate.” The cable concludes with a detailed, hour-by-hour chronology of the events of the night of June 3-4.

I Have No Enemies: My Final Statement

By Liu Xiaobo

Nobel Lecture in Absentia, December 10, 2010

Liu Xiaobo, who was already famous among China’s literary elite in 1989, was a conspicuous target for state retribution. He would eventually be sentenced to 11 years for subversion, and it was during that sentence, in 2010, that he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

Twenty years have passed, but the ghosts of June Fourth have not yet been laid to rest. Upon release from Qincheng Prison in 1991, I, who had been led onto the path of political dissent by the psychological chains of June Fourth, lost the right to speak publicly in my own country and could only speak through the foreign media…But I still want to say to this regime, which is depriving me of my freedom, that I stand by the convictions I expressed in my “June Second Hunger Strike Declaration” twenty years ago — I have no enemies and no hatred. None of the police who monitored, arrested, and interrogated me, none of the prosecutors who indicted me, and none of the judges who judged me are my enemies.

Also see: Liu Xiaobo’s Three Refusals: No Enemies, No Hatred, No Lies: An Excerpt from Wealth and Power: China’s Long March to the Twenty-first Century, by Orville Schell and John Delury

Unforgotten

Human Rights in China

Human Rights in China’s series of profiles of June Fourth victims. “The project draws on the information collected by the Tiananmen Mothers — a group of family members of June Fourth victims and survivors — over nearly three decades, defying state-enforced amnesia and threats and harassment from the Chinese authorities.”

Black Night in June

By Arthur Kent, May 16, 2019

Previously unseen footage of the People’s Liberation Army’s assault on demonstrators in Beijing, shot by Canadian journalist Arthur Kent.

Also see:

- Photos of the Tiananmen Square Protests Through the Lens of a Student Witness, The New York Times, May 30, 2019: Incredible photos from Jian Liu, then a fashion design student who snapped 50 days’ worth of photos but kept them out of public view until recently

- HKFP Lens: ‘The students will prevail’ – Rare shots of Tiananmen Square, before and after the 1989 massacre, Hong Kong Free Press, June 4, 2019