What is Hong Kong for?

This is an op-ed from Antony Dapiran, a Hong Kong–based writer and lawyer, and the author of City of Protest: A Recent History of Dissent in Hong Kong. On Thursday, we will release a Sinica Podcast featuring Antony talking about the extradition law and protests in Hong Kong. If you are a The China Project Access member, you can get early access and listen to the interview right away.

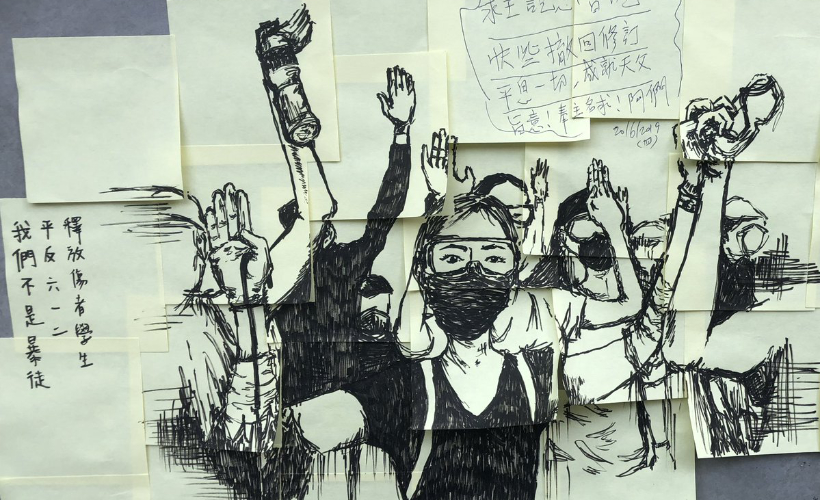

Top photo: Protest art in Hong Kong, photographed by Antony.

In the past two weeks, the world has watched the people of Hong Kong mount a series of protests against a proposed law that would facilitate the extradition of criminal suspects to mainland China. The protesters have won a temporary victory: The law has been put on hold, indefinitely. But the protesters’ victory is one not only for the people of Hong Kong: It is a victory for anyone around the world who is engaged in some way with China.

Hong Kong has long enjoyed a status as a safe haven. In the middle of the last century, it was a refuge for those fleeing a turbulent China, including a whole generation of artists, writers, and filmmakers. This generation of “Southbound” writers (南來作家 nán lái zuòjiā) included Jīn Yōng 金庸 (Louis Cha 查良鏞 Zhā Liángyōng), perhaps the world’s most famous Sinophone writer, and Hong Kong’s greatest director, Wong Kar-wai (王家衞 Wáng Jiāwèi), who came to Hong Kong as a child when his family fled Shanghai.

During the years that China was closed to the outside world, Hong Kong was the closest that most foreign scholars of China could come to the place — they studied with exiles from the mainland, and joined the tourists gazing from Hong Kong across the Shenzhen River into “Red China.”

In the decades that have passed since Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平 inaugurated his “reform and opening up” era, and following Hong Kong’s return to Chinese rule, much would appear to have changed. China is stable, prosperous, and open to foreign business and travelers. In this century, what is Hong Kong for?

It is still — as it always was — a place to do business, to be sure. While Hong Kong was once a foothold for international companies wanting to access the fabled “market of 1 billion customers,” it is now a stepping stone for mainland companies to access international capital markets, enter into cross-border transactions, and do business globally.

But in the post-handover era, there is more to Hong Kong than just business.

Hong Kong is the only place in the world that is a part of, and yet apart from, China; a place where researchers, analysts, commentators, writers, and artists can be sufficiently close to China to be well informed, to feel the zeitgeist, yet to work in an environment where they can express themselves freely; a place where NGOs like Human Rights Watch, or the China Labor Bulletin produced by Tiananmen exile Hán Dōngfāng 韩东方, can base themselves; a place where publishers can publish freely without restriction. (Taiwan, while it undoubtedly plays a similar and important role in the Sinophone world, remains a degree removed, both less close to China and less plugged into the global conversation.)

This haven status is given very tangible expression every year on June 4, when thousands attend candlelight vigils in Hong Kong’s Victoria Park.

But in recent years, that status has been increasingly under threat. Publishers of salacious books on China’s senior leadership disappeared from the streets of Hong Kong and reappeared in custody across the border. Financial Times correspondent Victor Mallet, one of the most senior members of Hong Kong’s foreign press corps, was booted out of Hong Kong after hosting a luncheon speech by Andy Chan Ho-tin (陳浩天 Chén Hàotiān), founder of the pro-independence Hong Kong National Party — prior to that party being banned by the authorities. A “national anthem law” that would make it a criminal offense to disrespect or parody the Chinese national anthem was proposed. (That law has also been temporarily put on hold in the wake of the recent protests.) Cultural institutions have denied platforms to dissident voices: The Asia Society refused to permit activist Joshua Wong (黃之鋒 Huáng Zhīfēng) to speak, and the Tai Kwun arts center canceled a talk by Chinese dissident author Mǎ Jiàn 馬建 (it relented after significant public pressure). In addition, Hong Kong Free Press was forced to cancel an event featuring Chinese-Australian artist Badiucao following threats to the artist’s safety.

In the words of local artist Samson Wong, in Hong Kong now, “What was not sensitive yesterday has become sensitive today; and what was not sensitive today will become sensitive tomorrow.”

The proposed extradition law would have been one more threat to Hong Kong’s status as a free haven, an additional factor that would go into the calculus that people make when considering whether to speak out — or to remain silent.

Accepting — as I assume most readers of The China Project do — that China is one of the most important stories in the world today, it is in the world’s interest to have a space where Chinese voices can speak freely, and where global voices can freely address Chinese audiences.

And so, when the Hong Kong people take to the streets, they are protesting not just for their own rights and freedoms, but also for the rights and freedoms of all of us. Theirs is a shared victory.

Also see:

Hong Kong ‘not ready to give up’: Historic protest against extradition bill