A campus divided: Hong Kong University students spar over city’s future

“Opportunities for friendly interactions are shrinking. I don’t want them to completely vanish.”

As protests in Hong Kong escalate in scale and intensity, tensions are mounting in other parts of the city, particularly on campuses where local students and those from mainland China share close quarters. This is most apparent at the University of Hong Kong (HKU), where a series of on-campus protests and counter-protests has fractured the community.

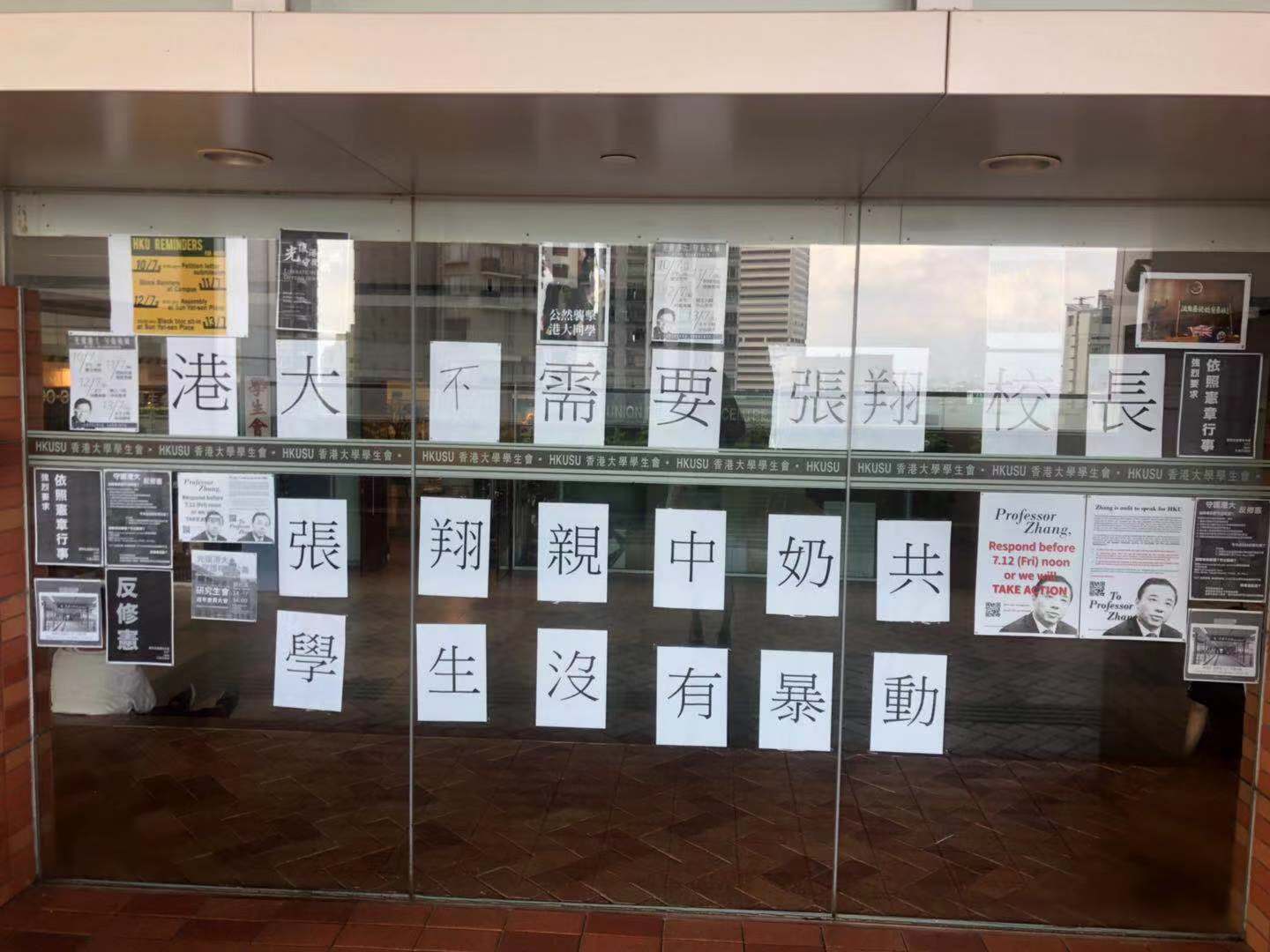

Things really soured earlier last month, when Zhang Xiang, the president of HKU and a Chinese-American physicist born in mainland China, issued a statement condemning the “destructive acts” of young protestors who broke into and vandalized the city’s legislative building on July 1. The HKU Student Union responded with a statement of its own, accusing Zhang of failing to respect the youth’s freedom of expression and understanding their frustration.

One week later, on July 12, a group of protesters, including many local students, marched to Zhang’s residence to demand a dialogue with him. Posters reading “Revive HKU, expel Zhang Xiang” were put up around campus.

A clear divide began to form between those from mainland China and those from Hong Kong; there seemed to be no middle ground.

According to several local students, although not all of them agree with the actions of the Student Union (SU), they generally support its political stance — in particular, they are united over their objection to a proposed (and now postponed) extradition bill, one that critics fear could threaten Hong Kong’s judicial independence from Beijing.

“I think SU was doing its job in expressing their concerns to Zhang,” said Kacey, a local student studying food and nutritional science. “Although some people do not agree with what they do, I personally understand their feeling and intention. They just want to protect their home.”

But as time passed, vulgar posters and graffiti began appearing on campus, leading some mainland students to call Zhang a victim of “campus bullying.”

On July 15, around 200 non-local students, many of whom were from mainland China, wrote an open letter to the school’s governing body asking it to “stop the language of violence, safeguard our equal rights, and sustain normal academic activities on campus.” As of August 1, more than 16,000 people have signed an online petition called “Support the President of HKU.”

“I feel the conflict between local and mainland students has intensified, especially after the rally at Zhang’s house,” said Rose, a local student who graduated from HKU a month ago. “Many mainland students are outraged, with increasing discontent toward local students.”

Rose was born in mainland China and moved to Hong Kong in middle school. She has developed friendships with both local and mainland students; she uses WeChat with mainland friends and Facebook with local friends. She said she has observed many instances of the two groups failing to understanding one another, describing it as “a chicken talking to a duck” (鸡同鸭讲 jī tóng yā jiǎng).

“It’s like two different worlds on Facebook and on WeChat,” she said. While local students frequently post about the anti-extradition protests, mainland students seem to largely ignore them. “There are mainland students who care about the protests,” she said, “but most of them don’t really express their concerns on social media.”

A campus politicized

Since 1997, mainland enrollment at HKU has increased significantly. As of the 2018-19 academic year, there are around 3,000 mainland students, including undergraduates and postgraduates, accounting for 15 percent of the total student population, according to the University Grants Committee. That enrollment figure is a 50 percent increase from just eight years ago. (In 1996-97 — the last year before Hong Kong’s handover from Great Britain — there were only 266 mainland students.) Local students take up 77 percent, and international students account for 8 percent.

Prior to this summer, HKU was already notorious for having a segregated student population. Many, including students and faculty members, have criticized its lack of diversity and failure to include non-local students in campus activities. In May 2019, a Korean American student wrote an article detailing her exclusion from many aspects of school life and her frustration in trying to integrate with locals. The article was widely shared among non-local students.

“While HKU has students from many different backgrounds and countries, people don’t seem to mix very well,” said Tracy, a sophomore from Hong Kong.

The segregation is starkest between local and mainland students, even though they share the same ethnic roots. According to academic research by Xiaoli Tian, a sociology professor at HKU, the larger socio-political climate “puts students on defense” when talking about politics. And social media has been flooded with polarizing commentary that makes it that much harder for students to talk to those with different points of view.

Anne is a mainland student who studied at HKU between 2014 and 2018. As the only mainland student doing translation studies, she learned to speak Cantonese within a year and made many local friends.

“The impact of the larger political climate on campus was huge,” she said. “When I was in college, as a non-local student, as long as you are willing to make a commitment, learn Cantonese, and try to integrate into the local communities, you could. And local students were most likely to welcome you.

“But now, that is not the case.” She added that it’s become increasingly difficult to befriend people with different ideas. When small talk between friends touch on politics, local and mainland students are very likely to have conflicting political stances, and arguments become inevitable.

Alex, a local student who graduated from HKU in 2016, cited a Chinese proverb to explain the escalating mainland-HK tensions: “Three feet of ice is not frozen in one day” (冰封三尺,非一日之寒 bīng fēng sān chǐ, fēi yī rì zhī hán). His implication is that locals are merely reacting to what feels like years of mainland Chinese encroachment: wealthy mainlanders gobbling up real estate, Chinese tourists causing shortages of Hong Kong commodities, Beijing introducing “national education” into Hong Kong’s academic curriculum, etc. “When local and mainland students talk about sensitive political topics and have incompatible views, they are likely to engage in arguments and to use mainland-HK differences as a justification,” he said.

“As the conflicts have intensified, peace-loving local students don’t usually take the initiative to talk to mainland students, as that could get them into trouble,” he added.

Shared frustration

Many students interviewed for this story, both local and mainland, feel frustrated with the divided campus culture, and agree that it is important to facilitate more communication between the two groups.

Tracy currently has no friend from the mainland, but she said she has no problem with them. “I think that’s the whole point of university, honestly: it’s to meet people of different backgrounds, and I’m not saying this just to sound good and inclusive.”

But many think, under current conditions, it’s virtually impossible to have meaningful conversations with groups with inherently different worldviews.

“I felt like I caught the last train,” Anne said, referring to her class of mainland students being the last to enjoy a truly open on-campus atmosphere where dialogue was possible. “Opportunities for friendly interactions are shrinking. I don’t want them to completely vanish.”

Canny, a local student who graduated last year, said she is pessimistic about the two groups coming together. “Most of the time, the two groups don’t communicate, as they perceive themselves as having different, conflicting views…At least for HK students I know, we would think it’s maybe too sensitive to talk to mainland students regarding those issues.

“I can’t really think of any way to bridge the different sides on campus.”

All last names in the story are omitted and some first names have been changed.