Uyghur love in a time of interethnic marriage

Since 2018, there has been a notable rise in articles promoting marriage between Han men and Uyghur women.

At a time when many people across China think of Uyghur men as potential terrorists and Uyghur women as potential fashion models, a new interethnic sexual politics is being institutionalized across Xinjiang.

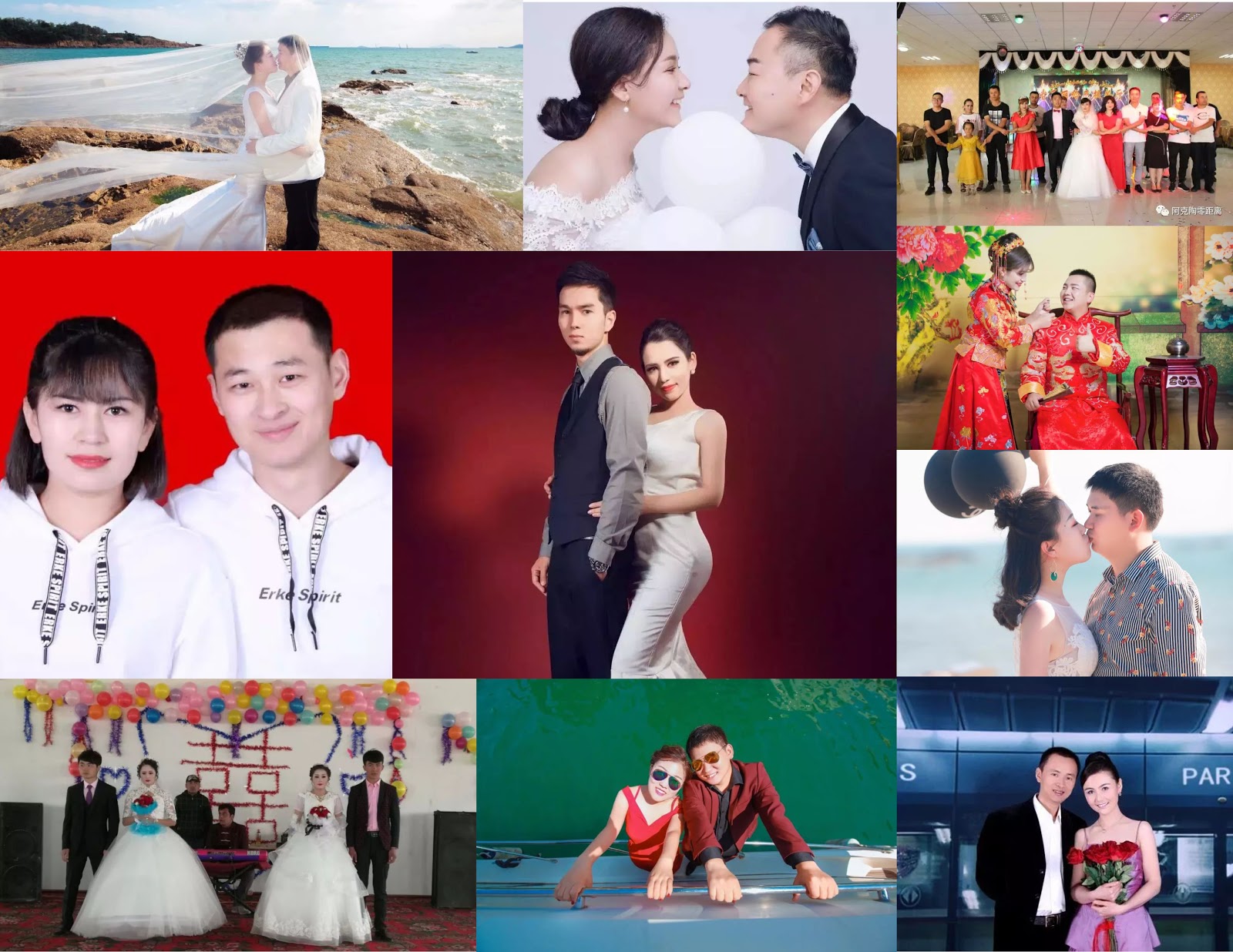

Image: From an interethnic marriage involving twin Uyghur sisters

and a Han and Uyghur man in Yarkand on March 14, 2019.

![]()

In May 2019, a young Uyghur graduate student in Europe who I’ll refer to as Nurzat received a WeChat video call from his panic-stricken girlfriend in a small city in southern Xinjiang. The young woman, who I’ll call Adila, told him that she would break up with him if he didn’t come back within the next several months to marry her. She said her parents were forcing her to do this. They thought that the risk of her being chosen for marriage by a Han young man was too high. They needed to find a Uyghur husband for her now, in order to protect her. Adila told Nurzat, “Please don’t blame me for doing this. A lot of Uyghur women are rushing to get married now. Everyone is afraid.”

Nurzat and Adila met when they were both college students in Ürümchi. She had been placed in a major that put her in line for a job in the police force back in her hometown, while he found a computer engineering track that led him to graduate school. Unlike previous generations of Uyghurs, whose marriages were arranged by their parents, they had chosen each other and had been in love for nearly five years.

In May 2017, Nurzat took a risky trip back to Xinjiang to see her. They spent 10 days in a hotel near the Ürümchi airport, seldom going out for fear that Nurzat would be checked by the police and questioned about his time abroad. He wore a baseball cap low over his eyes, thinking that this might help disguise his appearance. Yet, despite the care he took, not even calling his parents, he was nevertheless pulled aside for questioning on the street. His heart thumping, he handed the officer his old ID card from when he was a student in Ürümchi. The ID showed that his household registration was still in Ürümchi rather than his hometown in southern Xinjiang. Miraculously, it worked — the system, it seemed, hadn’t registered that he had traveled abroad and that he had graduated from college more than three years earlier. The officer returned his ID. Several days later he left to finish his Master’s degree, promising to return two years later.

Now two years had passed and their future “love marriage” had been thrown into question by the pressure of the Uyghur reeducation system.

A video that claims Xinjiang has always been a site of racial hybridity and that, now that it is “safe,” there are many beautiful Uyghur women who would love to have a Han husband.

![]()

Although historical rates of interethnic marriage between Uyghurs and Han Chinese has been a tiny fraction of one percent of Uyghur marriages, since 2018 there has been a notable rise in articles promoting marriage between Han men and Uyghur women. A recently published marriage guide, “How to win the heart of a Uyghur girl,” assumes that the reader is a Han man looking for a Uyghur woman. The author, Yu Longhe, who describes himself as a Han “volunteer” who works for the People’s Production and Construction Corps, begins by describing his impressions of Uyghur women as both stunningly beautiful and exceptionally caring. In doing so, he echoes a long history of Han erotic fantasies of Uyghur women. He notes, however, that it is important to not be so seduced by a Uyghur woman that one forgets to resolutely fight the three evils of “ethnic separatism, religious extremism, and violent terrorism.”

To get started, Yu advocates that the Han young man initiate the action by looking for opportunities to select a young Uyghur woman. After establishing a relationship, it is important to get the support of both sets of parents. The way to do this, he suggests, is by involving “social organizations” (社会组织 shehui zuzhi) and “local neighborhood watch cadres” (当地社区干部 dangdi shequ ganbu). While Yu notes that a marriage between a Han man and Uyghur woman is not a “traditional arranged marriage,” presumably since Han men maintain their agency in selecting a Uyghur woman, he nevertheless argues, “In an ‘ethnic’ love marriage, involving a third party (i.e. the government) is particularly important.” He suggests that “coordinating” between these local work units and social security workers will produce “strong backing and support” that cannot be defeated by “religious extremism.”

As an anthropologist who has spent several years studying gender and masculinity in Uyghur communities, I’ve been curious as to what the system described by this manual might look like from the perspective of Uyghur women. I wondered how it might fit into the panic Adila and Nurzat felt. Despite the stories and images of an increase in marriages between Han men and Uyghur women, no one has yet been able to determine the role of coercion in these marriages and their broader effects on Uyghur and Han society in the region. In order to begin to get some answers to these questions, a North America-based Uyghur collaborator I’ll call Abdulla contacted three of his former classmates, all young Uyghur women in southern Xinjiang who he had known for 10 years, to ask them about their love life. The responses he received from the young women, which were assessed by a North America-based female Uyghur researcher, who we refer to as Tumaris, were revealing not in the way they laid out definitive facts of how the process works, but in how it was reshaping their futures. Their accounts should be read simply as three perspectives from Uyghur single women who are being confronted with a changing reality in small Uyghur-majority cities in northwest China.

A video that argues the only reason Uyghur women have not married Han men in the past was due to culture and language differences, but that this is no longer a problem since Uyghur women are now fully trained in Han culture and Chinese language.

One of the first young women we contacted is someone I’ll call Gulmira, who now lives in a small city in southern Xinjiang. She said that, when it came to the lives of young Uyghur women, intermarriage was one of their most pressing concerns. She wrote, “Recently there are so many people getting married with the relatives.”

“Relatives?” we asked. To which Gulmira responded bluntly, using a term that Uyghurs use to refer to Han state workers, “Comrades. Do you understand what I mean?” She was referring to the more than 1.1 million mostly Han civil servants who have been sent to live in Uyghur homes over the past two years.

Continuing, Gulimara wrote that even though “people in the older generation don’t accept (these marriages with ‘comrades’), it has increased a lot. I don’t know if they are (doing it willingly) or not. I’m not in touch very much with those that have gone through with it. I think they must be doing it willingly. It seems like their families wouldn’t force them to do this. There are so many of them (that I personally know).”

Gulmira’s responses confirmed something that we heard from many members of the Uyghur community. Because it was seen as deeply shameful in the Uyghur community, both in Xinjiang and around the world, Uyghurs do not openly discuss why the number of marriages between Uyghur women and Han men have increased. Yet as we pressed her further, she began to reveal some of the ways in which pressure, if not coercion, has been exerted on Uyghur women to consider Han partners.

“Are you also thinking about (marrying a Han man) too?” we asked.

Gulmira responded, “Not now. I’ll delay it as long as I can by buying some time.”

Sensing that, in her mind, her eventual marriage to a Han man seemed inevitable, we asked, “Are there activities to date ‘comrades’?”

Gulmira rplied, “There are so many of these.” In her message, Gulmira emphasized this by adding an intensifier to the word “many” (Uy: jikku) to make clear that these activities were happening all the time.

“OMG, I can’t believe this,” Abdulla said, and then, using the common euphemism for the reeducation camps, asked, “If people say no to dating, will you go to ‘study’?”

Gulmira wrote: “Maybe even worse than ‘study.’” She said that her employer regularly organized “dance parties” on Friday evenings for the Uyghur women and Han “comrades” who worked at her firm. She wrote that she and other young women she knew tried to come up with excuses to not attend, ranging from feeling sick to having a date with a boyfriend. She said that the excuses had to be convincing or else her boss would become suspicious.

![]()

Some of these dynamics are also a product of the removal of a significant percentage of young Uyghur men from Uyghur social life. Another young woman who we will call Bahar pointed out that this absence adds to the new social pressure to marry Han men. In a series of text messages, she wrote that because so many young Uyghur men have been interned in her small city in southern Xinjiang, it is difficult for her to find a willing Uyghur marriage partner. Bahar noted that nearly all the Uyghur men who remained outside the camps worked as informants or low-level police officers and had low moral character. Many of them took advantage of the desperation of unmarried Uyghur women. Although Uyghur people often note that forms of patriarchy and male infidelity have been widespread in Uyghur society for decades, Bahar said that these forms of sexism have significantly worsened over the past several years.

She wrote, “The cheating is getting worse, because there are fewer and fewer men. Now there are many women who are over 30 who are still not married or who have lost their spouse. This has created a huge imbalance. That is why so many of ‘our’ girls are getting married with these ‘comrades.’”

Another one of Abdulla’s classmates, Rizwangul, confirmed that, in her small city, a similar dynamic was happening. But, unlike Bahar, she said she had a prospect that helped stave off her desperation. Rizwangul wrote, “There is a Hui boy chasing after me. He is so nice to me, I think he will cherish me in the future. He is nice to me and has a good personality. I am thinking as long as he does not create sorrows for me and makes me happy, that is good enough.”

Rizwangul had consigned herself to a “good enough” marriage with a man from another minority ethnic group, which, while not Uyghur, was at least Muslim.

Many of the state-approved online testimonials of marriages between Han men and Uyghur women seem to follow the trajectory outlined in the guide “How to win the heart of a Uyghur girl.” A Han security worker chooses a Uyghur woman, initiates contact, works with local authorities to convince the families to agree, and the marriage commences with gifts provided by local authorities. In nearly every published wedding narrative, the presence and support of local cadres and the visiting “relatives” is a major feature. For instance, in this double wedding of twin Uyghur sisters in Yeken to a Han volunteer and local Uyghur young man, the “county civil affairs bureau, town government cadres, the visiting ‘relative’ cadres, and the armed police all came to give their blessings.”

In another wedding story, a young Han construction worker from Gansu who had recently joined the People’s Production and Construction Corps spotted a Uyghur young woman working in the cotton fields. With gifts totaling 2,000 yuan ($290) and the backing of the township Party committee, the county-level cooperative, the “relatives” task force, and a religious management committee, the young man successfully married the young woman. In a short speech that repeated the terms “ethnic solidarity” (民族团结 mínzú tuánjié) 10 times, Jiang Tao, deputy secretary of the township party committee, told them they were a “model” for the township.

The thoughts of the deputy secretary were echoed in an essay published by the Chinese State Religious Network by an anthropologist named Mou Tao, who had “volunteered” (志愿 zhìyuàn) to work in the Uyghur reeducation system in Khotan prefecture. Drawing on her training at Minzu University in Beijing, she argued that “inter-ethnic marriage was a very important step in achieving national unity” because the marriage was not simply the joining of two people, but a relationship between two families. She posited that the main force keeping Uyghurs apart from Han was the “three evil forces.” In a line of argument that resonates with an influential study from the retired Peking University professor Ma Rong, one of the academic architects along with Hu Lianhe and Hu Angang of the state’s approach to Uyghur reeducation, Mou argued that inter-ethnic marriage should be normalized. She ends the essay with the following policy suggestions:

In the future, we must impose strict punishment on irresponsible remarks regarding marriages between young Uyghur and Han men and women and prevent isolation and threats toward those who intermarry. The government must also introduce relevant policies and measures to ensure the regular communication between young Uyghur and Han men and women. In addition to creating a good social atmosphere, appropriate rewards should also be given to the marriage of Uyghurs and Han; and care and preferential policies should be given to the children that come from Uyghur and Han marriages which face more social pressure.

This essay appears to encourage the institutionalization of the pressures that confront Adila and many other Uyghur women to marry Han men. Work units, neighborhood watch cadres, and visiting relatives are creating social situations and career-enhancing rewards for young Han men to pursue Uyghur women, while at the same time punishing those that speak badly or strive to prevent these interethnic marriages. In May 2019, Xinjiang authorities announced that the children of mixed-ethnicity marriages in which one parent is Han would receive 20 extra points on college entrance exams, while children in which both parents are ethnic minorities would only receive 15 (cut down from 50 points, a 70 percent decrease).

At a time when many people across China think of Uyghur men as potential terrorists and Uyghur women as potential fashion models, a new interethnic sexual politics is being institutionalized across Xinjiang. The exoticization of ethnic minority women by Han sex tourists has long been a feature in Chinese popular culture, but the active pairing of Han men with Uyghur women by state authorities marks a departure. It is one of the first times that minority women have become the sexual target of state institutions.

There is a great deal about the scale of new interethnic marriages between Uyghur women and Han men that must yet be examined. In general, state workers have hidden payment schemes, career advancement opportunities, and methods of coercion that incentivize Han men to follow through with these state-sponsored forms of political “intimacy” — an aspect of colonial rule that is key to establishing a new social order. We were not able to fully explore the forms of complicity that Uyghur women might pursue in order to protect themselves and their families and distance themselves from their devalued ethnicity. Nor were we able to fully examine the way some Han men may truly attempt to recognize their power and privilege as the embodiment of the colonizer and come to see themselves as allied in Uyghur struggles (something that the marriage manual advises against). Yet while many of the questions concerning this are unanswered, it’s worthwhile to push into the open what the feminist theorist Donna Haraway might refer to as “situated knoweldge:” knowledge of what interethnic marriage looks like from the embodied perspective of Uyghur women who experience these pressures as disempowering. We hope that this essay will be read as an invitation to begin a broader conversation around state-sponsored sexual violence.

In one of their last video chats, Nurzat promised Adila that he would come home in the next several months. Adila said she would buy a wedding dress and wait for him to arrive. But Nurzat knows that this may never happen. Adila likely knows this too. When their conversation turned to the future of Uyghur society, she scribbled a handwritten note which said, “We will never rise again.” After holding it up to the camera for a second, she popped it into her mouth, chewed methodically, and swallowed.

![]()

Darren Byler’s Xinjiang Column is published on the first Wednesday of every month. Previously: