The impossible politics of doing business in ‘China’

The Taiwanese fruit tea chain Yifang recently found itself battered by — successively — mainland Chinese internet users, Hong Kongers, and Taiwanese customers. They’re not the only company that has recently found itself caught in this three-way crossfire.

On August 5, some Hong Kong employees of Yifang Taiwan Fruit Tea (一芳台灣水果茶 yīfāng táiwān shuǐguǒ chá), a tea chain that owns 1,200 stores worldwide, including 29 in Hong Kong, went on strike in solidarity with protesters of a controversial extradition bill. “Closing the business for a day with the rest of Hong Kong. Hong Kongers, add oil!” a sign on one of Yifang’s franchise stores in Hong Kong read. (“Add oil” is the literal translation of an expression of encouragement and support.)

As those pictures circulated online, a predictable backlash ensued: Roars of disapproval from Chinese mainland internet users unnerved the Taiwanese brand’s franchises in China, where it owns more than 1,000 stores. “[We] resolutely safeguard ‘One Country, Two Systems’ and resolutely oppose violent strikes,” the company wrote on Weibo, claiming that it had immediately terminated contracts with stores that participated in the strikes and would “never allow any attempt to split the country.”

It shouldn’t be hard to understand why Yifang chose to issue such a response in mainland China, where multinational businesses are increasingly pressured to publicly take Beijing’s stance on political matters involving its territorial claims.

In December, acclaimed Taiwanese baker Wu Pao-chun was put under the spotlight in China — where he had just opened a store — as people accused him of supporting Taiwan independence. While his exact words back in 2016 — that he would focus on expanding not only to the Chinese market but the world’s — hardly bore any such implication, a boycott was already on its way. Wu ended up issuing a statement proclaiming that he came from “Taiwan, China,” and was “proud to be Chinese.”

In July, Japanese sports drink brand Pocari Sweat pulled advertising from pro-Beijing broadcaster TVB amid the Hong Kong protests, to the chagrin of mainlanders. A similar series of boycotts followed, pressuring Pocari Sweat to write an apology letter, affirming that it supports “One Country, Two Systems” and Hong Kong’s Basic Law.

“One Brand, Three Systems”

Pleasing one group of people, however, can mean infuriating another. Yifang’s statement in China was, unsurprisingly, received poorly in Hong Kong, as well as back home in Taiwan.

In Hong Kong’s Sham Shui Po, the sign of one Yifang store was vandalized: a few strokes were added to the word 一芳 (yī fāng), making it 共芳 (gòng fāng), or “Communist-fang.”

Confronting baffled and enraged Hong Kongers, the company’s office in Hong Kong clarified that it does not operate any Weibo account and that the mainland Chinese social media statement did not reflect its views.

“The Hong Kong general agent respects the individual political positions of the participating branches and firmly believes that Hong Kong is a free, open place that can accommodate diverse opinions,” Yifang Tea Hong Kong wrote in a Facebook post. “This is also the core value that Hong Kong people adhere to.”

In Taiwan, another round of boycotts was on its way against Yifang’s Weibo statement. Wang Ting-yu (王定宇 Wáng Dìngyǔ), a Taiwanese legislator affiliated with the Democratic Progressive Party, suggested on Facebook that he would boycott Yifang for its pro-Beijing statement. “For the people of Hong Kong, and for Taiwan, goodbye forever!” he wrote, attaching a list of brands owned by Inkism International, Yifang’s parent company.

Incensed Taiwanese nationalists also stormed the Instagram page of George Ko (柯梓凱 Kē Zǐkǎi), Yifang’s CEO, digging out photos of Ko with the Kuomintang figures Ma Ying-jeou and Terry Gou to prove the executive’s pro-China ties.

While several of Yifang’s Taiwan branches in Kaohsiung, Hsinchu, and Taipei have voiced support for Hong Kong’s protesters, criticizing the brand’s decision to side with Beijing, the brand’s headquarters in Taipei issued a statement on August 6, affirming that the company would “improve communication with partners worldwide” and “stick to the principles of not getting involved in politics.”

Yifang’s franchises outside Asia have also taken a step back, trying to stay away from the controversial Weibo post. In a Facebook post, Yifang U.K. announced that it “remains independent from any claims that have been made by other franchises in other regions.”

Not just Yifang

Mainland China is Yifang’s largest market, where it owns more than 1,000 shops and earns around 80 percent of its total revenue. It currently has 177 stores in Taiwan, 29 in Hong Kong, and 80 in the rest of the world. The chain’s franchise stores worldwide import most of their raw materials from Taiwan.

As it turns out, Yifang isn’t the only Taiwanese beverage chain that had to endorse Beijing’s territorial principles.

The Taiwanese milk tea brand CoCo found itself in a similar predicament when Chinese internet users, on August 6, found a receipt from a CoCo store in Hong Kong that read, “Hong Kongers add oil,” printed on June 16 — when a march against the extradition bill took place in the city.

The company responded that the message on the receipt was added by local staff, and that particular store in Wan Chai would be closed. “Hong Kong is an inseparable part of the People’s Republic of China. There is no room for uncertainty,” CoCo, which currently has nine stores in Hong Kong, wrote in a statement on August 9.

Taiwanese nationalists have also found other beverage chains — household names such as Gong Cha, Meet Fresh, Chatime, The Alley, DaYungs — taking pro-Beijing territorial claims, either using the term “Taiwan, China” or supporting the 1992 Consensus. As many of these claims were made on the Chinese internet — WeChat and Weibo — many Taiwanese have only recently unearthed them.

Last August, Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen dropped by an 85°C Bakery Café — a bakery chain originating in Taipei that, not unlike Yifang, has more than 1,000 locations worldwide — during her Los Angeles stopover. It was a brief visit, but enough to infuriate those on the other side of the Taiwan Strait, who called for a boycott of the bakery brand. Many delivery apps removed the chain from their platforms. The company ended up announcing that it supports the 1992 Consensus — which outlines the “One China principle” — before the event escalated into a total PR disaster.

85°C was fortunate, relatively speaking. When Marriott International, the American hotelier, listed Tibet, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macao as separate countries from China in a customer survey back in January 2018, China’s cyberspace authorities temporarily shut down Marriott’s Chinese-language website in China.

Later, when a Marriott social media staffer from Omaha, Nebraska — who probably had no idea about the complexities of Chinese politics — liked a tweet from a pro-Tibetan independence group using the company’s account, the 49-year-old was immediately fired.

And when China’s civil aviation regulator requested international airlines to amend their online references to Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan a year ago, those who did not comply faced consequences in China — a New Zealand aircraft bound for Shanghai, for instance, was forced to fly back. But those who did comply faced backlash in Taiwan. While the policy caught the attention of President Donald Trump, who blasted China’s actions as “Orwellian nonsense,” U.S. airlines ultimately dropped country descriptors altogether for Taiwanese airports.

Back in May, when a Taiwanese student protested Harry Potter official website Wizard World’s use of the term “Taiwan, China,” the website complied with her request, to the chagrin of Harry Potter fans in China, who called for a boycott of J.K. Rowling’s work. The site then updated the webpage again, changing “Country” to “Country/Region” and restoring the “China” suffix.

The latest targets in China are designer houses Versace, Coach, and Givenchy, all of which have printed t-shirts that list Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan without “China” following them. The all-too-familiar backlash have been followed by all-too-boilerplate letters of apology.

Even Huawei — the Chinese telecommunications company under scrutiny of foreign governments — has been caught in the maelstrom. Back in 2011, the company’s Taiwan Facebook page celebrated Taiwan’s national day by writing “Happy birthday to our country!” and posting a Taiwanese flag, which really upset those on the mainland. Chinese phone brand Oppo did something similar when its Facebook account posted the image of a Taiwanese flag on national day in 2014.

“Fruit tea is best when it is natural. If you add politics, it does not taste good,” Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen said, responding to media inquiries of Yifang’s predicament. But for multinational businesses operating in China, political neutrality is impossible — the consequence of widening rifts between mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong.

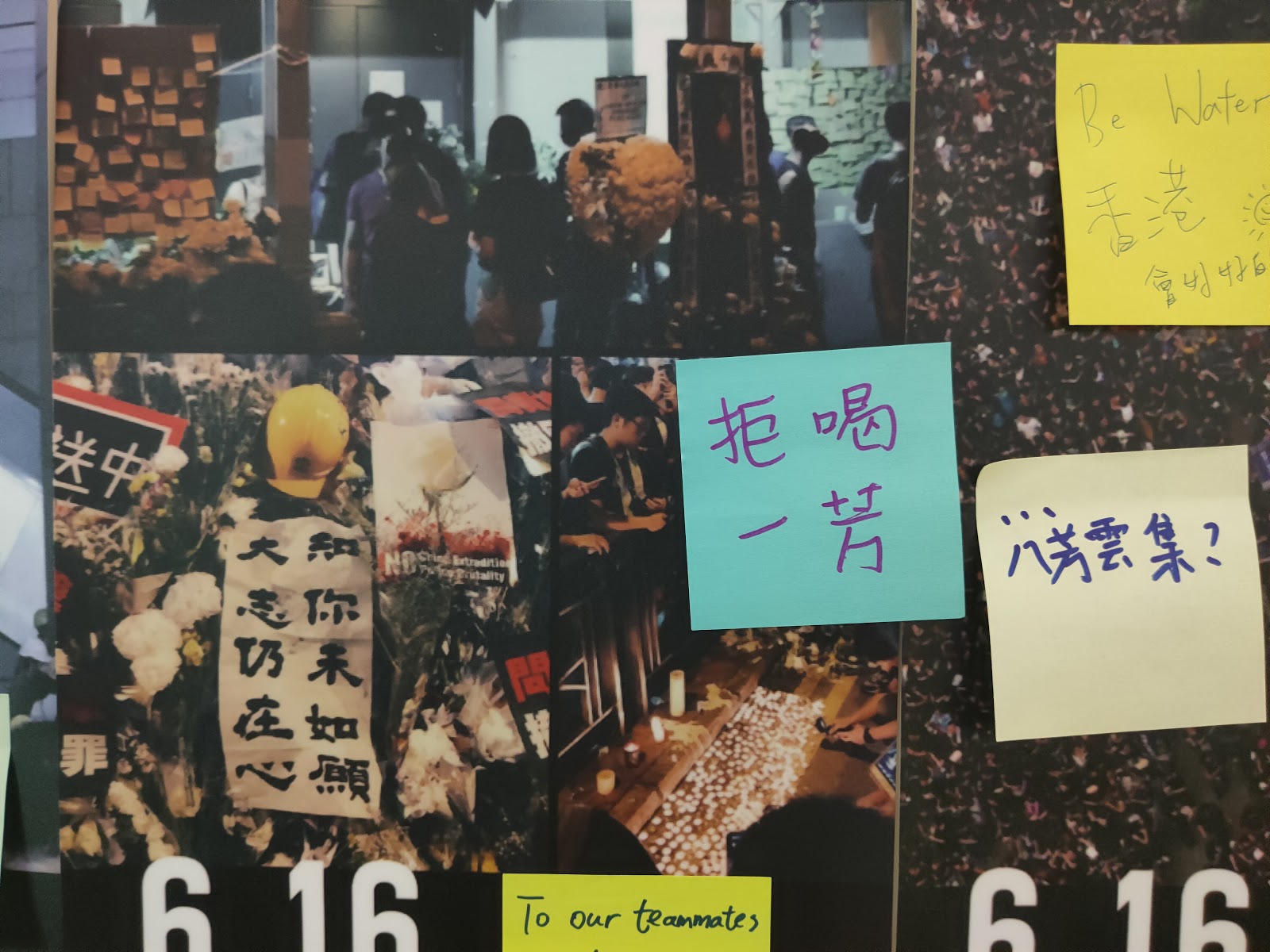

Top picture: “Boycott Yifang,” reads a sticky note on Taipei’s Lennon Wall inside an underpass near National Taiwan University. (Tianyu M. Fang)