Chinese web censorship works. Unfortunately, it’s never going away

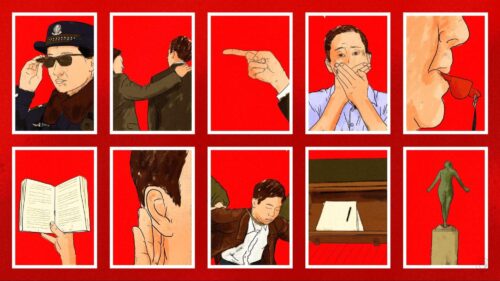

While protests continue in Hong Kong, the government on the Chinese mainland has been increasingly aggressive in its propaganda, painting the demonstrators as violent “rioters,” even “terrorists.” One reason the propaganda is working? Because internet censorship has blocked the vast majority of articles and videos that express even the slightest support for the protesters.

Internet censorship is the topic for this week’s Kuora, which comes from one of Kaiser’s answers originally posted to Quora on August 3, 2010.

When will China’s web censorship stop and the government’s attitude change?

As long as the Communist Party remains in sole possession of political authority in China, it’s not likely that web censorship will ever truly “stop.” Beijing has an abiding concern with social stability, which is believed to be a necessary condition for continued robust economic growth, which in turn is (circularly) a prerequisite for social stability. It’s worth pointing out, I believe, that this is a prioritization quite widely shared in Chinese society. The Party essentially holds that a truly unfettered internet would represent an existential threat to Party control.

I believe that in this last decade, the year 2007 was probably the year when internet censorship in China was least onerous. This is true for both the “Great Firewall” style of censorship aimed at preventing or at least discouraging users within China from accessing certain sites outside of China, and the “self-discipline” style of censorship by which the state compels internet companies to monitor and redact or otherwise censor “sensitive” political content, pornography, extreme violence, etc. There are some who would argue that 2007 represented some sort of “intended trajectory,” a move toward increasingly lenient internet censorship policies that was interrupted or pushed off track by unexpected events like the Tibetan riots of March 2008 and the Urumqi (Xinjiang) riots of July 2009; and by the convergence of many “sensitive dates” like the 20th anniversary of the suppression of the student-led uprising in Beijing, the 60th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic in October 2009, and so forth. Whatever the case may be, at this point there are now even more of these “sensitive dates” and I can’t envision a let-up anytime too soon.

The other factor to consider is the newfound political potency of the Chinese netizenry. In the last two years, even as there’s been an indisputable tightening of controls on the internet in China, we’ve seen at the same time a marked increase in the power of online public opinion. Officialdom, from its loftiest ministers down to the lowliest county functionaries, is keeping a close eye on what people are saying online, constantly taking the temperature of public opinion as measured by online sentiment. Granted, they’ve always watched public opinion; but in recent years, there’s been a palpable sense of empowerment on the part of China’s internet users, and each case in which decision-makers appear to bow to the will of the online masses only emboldens them. To some extent, this is useful to Party elites: It serves as a kind of check on official malfeasance, of the sort that, left to fester, could really create a firestorm of discontent; and it serves as something of a release valve. Better to have people spewing venom and raging against political abuses online, the reasoning goes, than to have them doing it in the streets. But the bottom line is that this will never be allowed to go too far: Once it’s no longer deemed to serve a useful purpose, it can and likely will be circumscribed.

As for the other part of this question — when will the government’s attitude change? — I think there are clear cases where we’ve seen changes in the nature and practice of censorship. In 2005, for instance, most of the sites that were blocked (aside from the “usual suspects,” i.e., websites of human rights organizations, of organizations promoting Tibetan independence or Taiwan independence, of dissident pro-democracy groups outside of China, of the Falun Gong cult) were mainstream media sites, like Time, CNN, BBC, the New York Times and so forth. In 2010, the focus was on Web 2.0 sites like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube — sites that allow for many-to-many communication and for organization. The same is true with domestic self-discipline censorship: Efforts are more focused on community sites (social networks and microblogs, UGC-heavy video sites, etc.) than on the more traditional Web 1.0 sites.

Attitudes will continue to change, but only in terms of implementation, prioritization of perceived threats, and so on. But I see little to no chance that the Party will abandon its prerogative to censor the internet, and I see few serious challenges — either political or technological — to its ability to impose at least some level of control on information within China.

Kuora is a weekly column.