Independence activist Su Beng dies at 100, believing until the end that ‘Taiwan people need to persevere’

Revered Taiwan independence activist and trusted adviser to Tsai Ing-wen, Su Beng, passed away on Friday at the age of 100. This was one of his final interviews.

Last week’s loss of two of the last countries to recognize the government of Taiwan may have made international headlines, but for Taiwanese who hope that their home can be an internationally recognized country one day, the real loss was the passing of centenarian Su Beng (史明 Shǐ Míng), who died of pneumonia late Friday night.

Born in Taiwan in 1918 when it was an Imperial Japanese colony, Su would go on to live an epic life of cinematic proportions that threaded the seismic upheavals of the past century in Taiwan, China, and Japan. To his dying day he supported social movements in Taiwan aside from independence, such as the push for same-sex marriage, while also voicing solidarity for movements in China, including Tibetans and pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong.

Drawn to Marxism as a student in Tokyo in the late 1930s, Su fought the Japanese alongside the Red Army in China, where he also spied against the Kuomintang of Chiang Kai-shek (蒋介石 Jiǎng Jièshí). After returning to Taiwan to escape the brutality of China’s land reform under the Communists, Su’s plot to assassinate Chiang was foiled by the KMT, forcing him to flee to post-war Japan, where he ended up running a popular noodle shop that also served as a front for a militant Taiwanese revolutionary group. After Chiang’s passing, he switched to promoting peaceful change in Taiwan, where he returned in 1993 after the end of 38 years of KMT martial law and the first democratic elections.

While many observers inside and outside of Taiwan opine that unification with China, which most Taiwanese do not seek, is inevitable, Su long said that true independence — i.e., casting off the legacy government of Chiang’s Republic of China and creating a true Taiwanese state — is just around the corner.

“Taiwan is bound to prevail,” Su is reported to have said with his final words, adding one last endorsement for Taiwan’s president as she seeks re-election in January: “Tsai Ing-wen must win.”

Su’s disdain for both the KMT and the CCP was no secret. Although many on the pro-independence side of Taiwan’s political spectrum view Tsai as too moderate — compare her to Chen Shui-bian (陈水扁 Chén Shuǐbiǎn), the only other president to have come from the Democratic Progressive Party — Su was a strong supporter, speaking up in her defense when party elders criticized her. Speaking with me earlier this year, he made his views on the upcoming Taiwanese presidential election clear.

“If Tsai isn’t re-elected,” he said, his piercing right eye looking at me as he paused briefly, “the Kuomintang will hand Taiwan over to the Communist Party.”

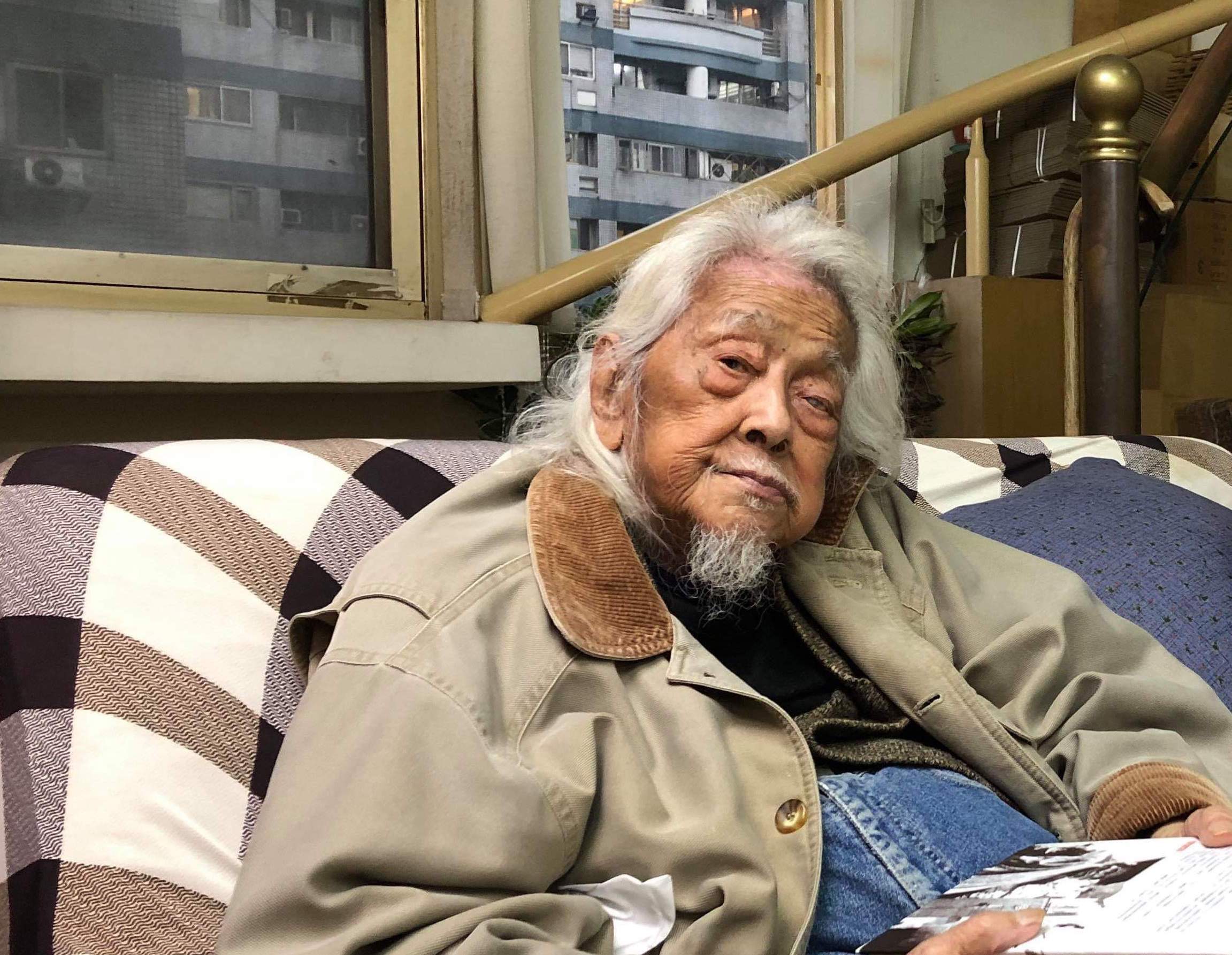

In a March interview, the centenarian welcomed me into his home in New Taipei City, where several assistants would help him get through his day. He wore a sweater and coat, as homes in Taiwan’s subtropical north tend to not have heating. His white shoulder-length hair and wispy goatee were complemented by a countenance that radiated both a grandfatherly kindness and the air of someone who’d seen it all.

“I’m too old,” he said apologetically after giving me a firm handshake and sizing me up with his right eye, which, unlike his foggy left eye, conveyed a sharp focus. “It’s not so easy for me to hear, or talk or move around now.”

Despite his years, or perhaps because of them, we spoke for 75 minutes, a length that many people less than half his age might find tiring. I was aided by a translator, Lan Po-shih, a friend of Su’s who simply refers to him as 欧吉桑 (ōujísāng) — the Mandarin pronunciation of a Japanese word for “uncle” or “old man.” I asked my questions in Mandarin, and bending toward Su’s ear, Lan would yell my question in Taiwanese, a local version of the ancient Hokkien language that is impenetrable to a mere Mandarin speaker. Su occasionally peppered his speech with English: “intelligentsia,” “power,” “rise up.” All the while, his face and hands remained animated, betraying a youthful energy within his century-old frame.

An English word he dropped more than once was “contradiction,” highlighting the influence Marxism still held on his worldview. Brought up steeped in Chinese culture, he was a young friend of Taiwanese activists who opposed Japanese colonial rule of Taiwan, which lasted from 1895 to 1945. Su excelled as a young student and went on to study politics and economics at Waseda University in Tokyo. While there, he became enamored with Marxism, largely due to a CCP member’s reading group.

Soon Su headed to the war-torn Yangtze Delta, where, according to his memoirs, he served as a Communist agent while working in Wāng Jīngwèi’s 汪精卫 puppet regime that answered to Tokyo, passing intelligence to the CCP. After the war’s end in 1945, he headed to China’s Communist-controlled northern region, where constant executions and other abuses by the CCP in the name of land reform led him and his girlfriend, Hiraga Kyoko, to leave for Taiwan. Thus ended eight years of cooperation with the Communists in China, an instructive period that would shape his worldview going forward.

“The Communist-liberated area back then lacked an international perspective,” Su told me. “Although Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping had studied in France, most of the cadres came from a peasant background. At that time, I remember thinking that it would be quite difficult for the CCP to occupy Taiwan.”

Japan’s surrender in 1945 was followed by U.S. forces effectively handing Taiwan over to Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist party, the Kuomintang, whose Republic of China party-state would relocate its capital from Nanjing to Taipei in 1949 after being routed by Mao’s forces. That was the same year that Su would return to his beloved Taiwan, which two years earlier had suffered the 228 Massacre, the KMT’s brutal response to a violent Taiwanese uprising that resulted in as many as 28,000 Taiwanese deaths. The KMT focused on eliminating an entire generation of Taiwanese civil servants, lawyers, doctors, and other intellectuals, and largely succeeded.

After 1949, Chiang and the KMT declared martial law and turned their attention to potential Communists in their midst, focusing on the so-called “outsiders” 外省人 (wài shěng rén), or mainlanders, that came over from China with them. So began a period of martial law in Taiwan that would last an astonishing 38 years, ending in 1987. Known as the White Terror, this period saw an estimated 140,000 people imprisoned and thousands executed.

Shortly after his arrival in KMT-controlled Taiwan, Su came to the conclusion that Chiang and company had to go. Su and other like-minded Taiwanese plotted to assassinate Chiang, but the KMT caught wind of the plan, forcing him and Hiraga to — as legend has it — catch a ride on a boat taking bananas to Japan in 1952. The following year, the couple opened a restaurant, New Gourmet (新珍味 xīn zhēn wèi), in Tokyo’s Ikebukuro neighborhood, where the stewed noodles (大卤面 dà lǔ miàn) and dumplings were best-sellers. Su would go on to run the restaurant for four decades.

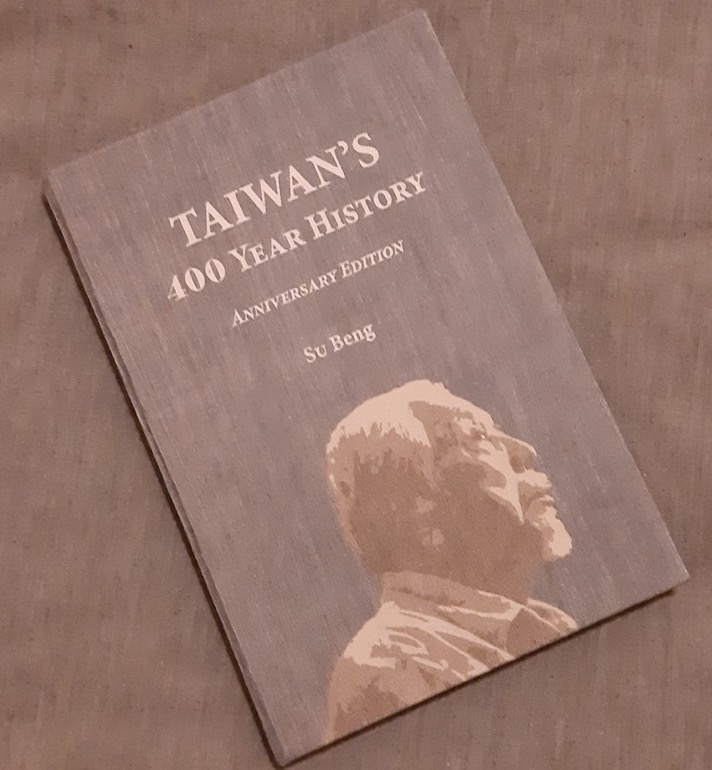

New Gourmet’s business was good enough to sustain Su and enable him to pursue a new project — a book that would elucidate the struggle of the Taiwanese people. When he wasn’t preparing bowls of noodles or boiling dumplings, he was exploring Japan’s imperial archives and other sources for information about Taiwan that would culminate in the 1962 publication of Taiwan’s 400 Year History (台湾人四百年史 Táiwān rén sìbǎi nián shǐ).

Originally published in Japanese, the book was the first to look at Taiwan’s history from a non-colonial perspective. Japan was first to colonize all of Taiwan, but before them, Qing and Ming loyalists led by Koxinga, the Spanish, and the Dutch had all colonized parts of the mostly mountainous island’s coastal plains.

Originally published in Japanese, the book was the first to look at Taiwan’s history from a non-colonial perspective. Japan was first to colonize all of Taiwan, but before them, Qing and Ming loyalists led by Koxinga, the Spanish, and the Dutch had all colonized parts of the mostly mountainous island’s coastal plains.

Banned in Taiwan by the KMT’s strict censorship apparatus, Su’s book wasn’t published in Chinese until 1980, by San Jose-based Paradise Culture Associates. By that time, the U.S., which was still a strong ally of the ROC despite having cut official diplomatic ties in 1979, had emerged as the primary hub of a growing overseas Taiwanese movement against the KMT.

“Su Beng knew very well how the Communists functioned, and the KMT is more or less run like the CCP,” said Dr. Tun-Hour Lee, a professor at Harvard’s TH Chan School of Public Health. When Dr. Lee arrived in the U.S. as a student on July 4, 1976, the Taiwanese independence movement — which effectively sought independence from the KMT’s Republic of China — was gathering steam back home. It was also benefiting from a large number of Taiwanese studying in the U.S., many who specialized in law and would use it to change the ROC from within. For students like Lee and other members of the Taiwan diaspora in the 1980s, Su’s book provided an eye-opening look at their own history and identity.

“To me, his book offered those Taiwanese who did not have his life experience the basis of why and how to struggle against the oppressor,” Lee said.

In addition to his restaurant and book endeavors, Su also founded the Taiwan Independence Association in 1967. He estimates that he trained thousands of Taiwanese who visited his restaurant, ostensibly as tourists to Tokyo, in the art of armed struggle — including bombmaking. He also claimed in his memoirs and interviews to have made surreptitious trips from Japan to Taiwan, where he bombed several trains.

After Chiang’s death in 1975, Su switched to non-violent struggle, and in the 1980s he took his quest for Taiwanese independence on the road, visiting Taiwanese communities across the U.S. and elsewhere. Back in Taiwan, big changes were taking place, with the founding of the Democratic Progressive Party in 1986, which was technically illegal under martial law, which Chiang’s son and successor Chiang Ching-kuo (蒋经国 Jiǎng Jīngguó) would end the following year. The younger Chiang’s death in 1988 opened the way for the rise of Lee Teng-hui (李登辉 Lǐ Dēnghuī), the first Taiwanese-born ROC president.

Lee nationalized the ROC army, which had previously sworn allegiance to the KMT — much as the PLA still serves the CCP today. In 1990, less than a year after the Tiananmen massacre, the Wild Lily protests led by Taiwanese students prompted Lee to introduce democratic reforms, with the first legislative elections in 1992 and the first presidential election — which Lee won — in 1996.

Heartened by Taiwan’s democratization and the growing public manifestations of Taiwanese identity in a country that had once been forced to identify as Chinese by the Chiangs, Su returned to his home in 1993. In the years since, he has been a tireless activist, speaking in support of Taiwanese sovereignty and self-determination as well as the Tibetan struggle. In more recent years, no longer able to speak in public, he still made appearances — he had just appeared at an event commemorating the March 9 Tibetan uprising the afternoon I met with him — while tweeting support for same-sex marriage and, more recently, the protests in Hong Kong.

什麼都不用說

愛下去就對了 pic.twitter.com/zxiNBFr8aK— Subeng1918(Su Beng-史明文物館) (@Subeng91) May 17, 2019

Caption: Nothing needs to be said. Love is right.

今日香港

是台灣的借鏡

我們沒有內鬥的本錢

2020台灣一定要贏借自@洪耀南相片 pic.twitter.com/lhgdCmblrB

— Subeng1918(Su Beng-史明文物館) (@Subeng91) June 9, 2019

Caption: Hong Kong today is the mirror of Taiwan. We don’t have the capital for infighting. Taiwan must win in 2020.

Su’s longevity and energy have undoubtedly inspired the next generation of Taiwanese activists.

Lan, our Taiwanese-Mandarin interpreter, proposed to his girlfriend at New Gourmet in 2015 (she accepted). They first met Su at a protest he led at National Taiwan University against China’s recently passed anti-secession law in 2006. “He was considering selling or closing the restaurant, so we basically decided to go while we still had the chance,” Lan told me. “He has had a big impact on us.” (The restaurant is still open, under different management, but with the same menu.)

Jenny Wang, co-organizer of Keep Taiwan Free, a New York-based coalition focused on raising awareness of and advocating for Taiwan’s democracy, said that Su has been a tireless champion of Taiwan’s unique identity. “Su Beng’s story is an inspiring reminder of how long Taiwan has been in this fight — and that it’s a fight still worth fighting,” Wang said.

As for Taiwan’s future, Su, in our conversation, was convinced that it would one day join the ranks of other countries without the cloud of threats from China hanging over its head — provided that the U.S. continues to support its unofficial ally.

“If the U.S. abandons Taiwan, then the relationship between China and Taiwan will lose its balance,” Su said. “All of Asia, the whole world, will be affected and will lose hope.”

“However,” he said, “the U.S. is a country that supports freedom and democracy, so I don’t see that happening. If the U.S. doesn’t give up Taiwan, China won’t be able to take it — Taiwan people need to persevere.”

Pausing for a moment and gazing across his living room as if he were looking across a century — perhaps one past, perhaps one to come — Su continued: “I believe, one day, Taiwan will finally be independent.”

Another pause.

“I won’t be around to see that.”

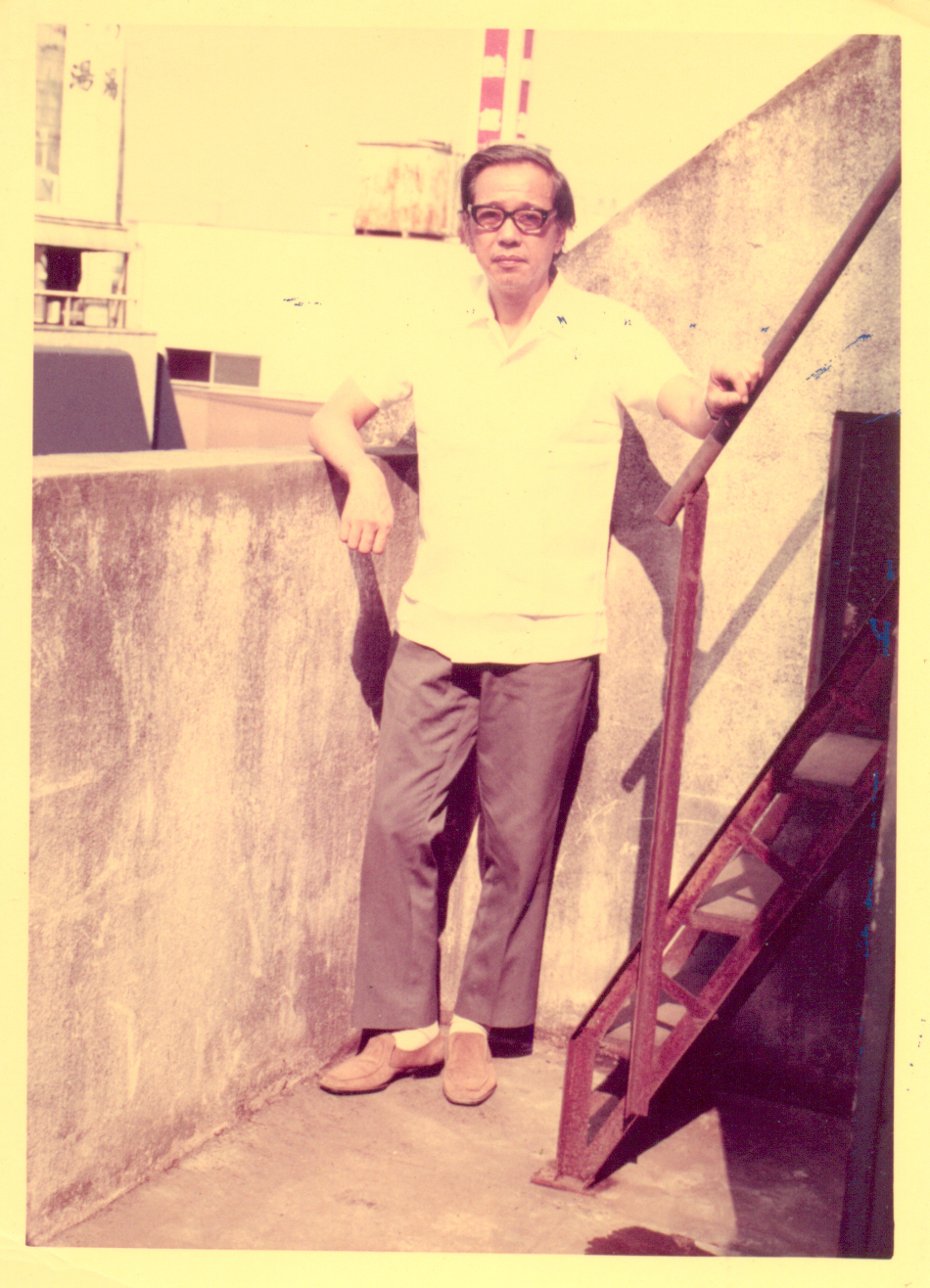

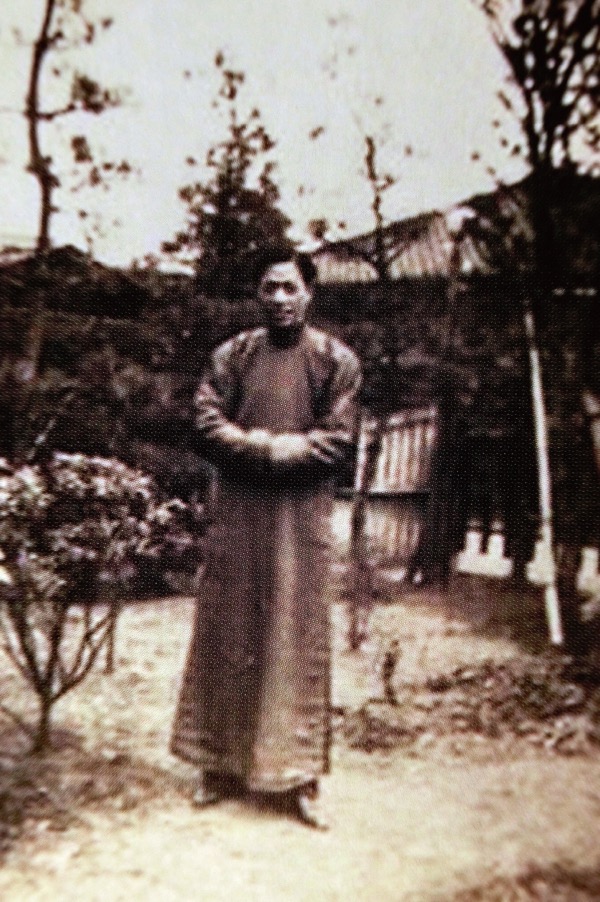

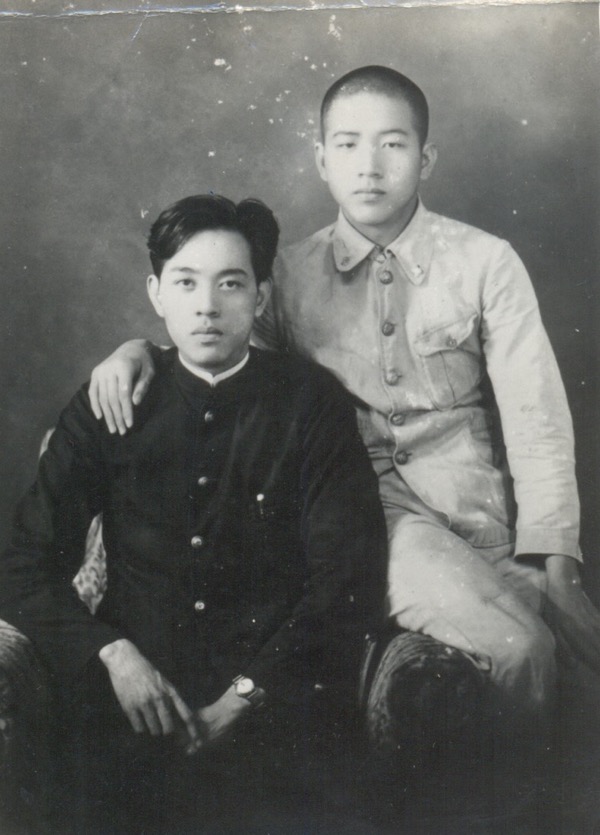

Left: Communist agent Su Beng in wartime Suzhou in the 1940s. Right: Su Beng with a Waseda University classmate.