China is not a technology superpower. Stop treating it like one

It’s a common argument in the debate about how to respond to China’s technology rise: Beijing is intent on “catching up and surpassing” the West in advanced technologies. The Chinese Communist Party’s ambition to make China “self-sufficient” in sectors like semiconductors, artificial intelligence, and quantum computing threatens to displace Silicon Valley and poses risks to the U.S. economy and military superiority, the argument goes.

The U.S. and China are embroiled in a $360 billion trade and technology confrontation largely because of how successfully the “catch up and surpass” meme has taken hold in Washington. But the underlying reasoning — artfully captured in recent pieces such as Julian Baird Gewirtz’s recent article in Foreign Affairs, “China’s Long March to Technological Supremacy” — is flawed. At best, it puts too much stock in the Chinese government’s ability to drive cutting-edge innovation. At worst, by ascribing technology superpowers to China, Washington risks an overreaction that could undermine U.S. firms’ own ability to innovate.

Like all good tropes, there is a kernel truth to concerns about China’s rising tech prowess. China’s big platform companies and a growing number of unicorns increasingly compete head-to-head with large Silicon Valley firms. The U.S. has no company comparable to Huawei in 5G. And unlike the U.S., Beijing isn’t shy about setting big industrial policy goals and throwing money at them. Under President Xí Jìnpíng 习近平, the Communist Party made a big show of programs such as Made in China 2025 and its New Generation AI Development Plan (AIDP).

The first mistake many Western observers make is assuming that aspirational government policies drive Chinese private-sector innovation and not the other way around. The second is to think that government rhetoric is the same thing as a coherent and achievable strategy. Both mistakes stem from confusion about how innovation works in the real world.

Here’s a reality check: When is China going to be able to develop “self-sufficiency” in cutting-edge semiconductors? Maybe never. Semiconductor manufacturing equipment? Maybe never. An alternative software stack for the cloud? Maybe for China, but not one that can compete globally. Enterprise software? Same.

China’s policy support for digital innovation has an uneven track record. The AIDP was out of date the moment it was published. And while China has caught up in simpler technologies like solar cells or high-speed rail, showy investments in more advanced sectors like semiconductors have failed to catapult China past the West — despite favorable government subsidies and what could generously be called a lax attitude toward intellectual property protections.

For Chinese technology companies, all this talk of tech dominance and self-sufficiency must seem odd. Huawei, Alibaba, and the like historically have tended to do what makes the most business sense — developing or acquiring technologies where they perceive they have a competitive edge, while relying on Western firms to fill in the gaps necessary to compete in global markets. And here, supposed shortcuts such as illicitly acquiring technology do not constitute a viable business model and can only provide limited benefits without an innovative workforce, stable and adaptive management, and a realistic long-term business model and strategy.

Huawei’s reliance on Google’s Android operating system for its smartphones is a good example — global consumers who dropped Huawei handsets after it was cut off from Android are unlikely to be tempted back by a home-grown Huawei alternative OS that will lack many popular Google apps. Huawei’s chip design arm HiSilicon may be China’s leading semiconductor success story, but Huawei’s investments in chips were not driven by government fiat so much as by the desire to drive down the cost of its smartphones and base stations by reducing the royalties the company pays to Western suppliers.

Although HiSilicon can now produce AI, baseband, and smartphone core processor chips on par with leading Western designs, it is far from “self-sufficient”: It relies on chip design tools from the U.S. and Germany, licenses microprocessor reference frameworks from ARM, and outsources manufacturing to TSMC in Taiwan, which uses fabrication techniques that Chinese mainland companies can’t hope to match.

This is the flaw of the “catching up and surpassing” meme. It is simply unfeasible for China — or any other country — to replace the high-tech ecosystems in which the country’s leading tech firms are embedded with home-grown alternatives.

Are Chinese tech firms catching up and overtaking U.S. and Western rivals in some areas? Sure, just like Japanese, South Korean, and Taiwanese companies did during a previous era of technology development. Chinese firms probably also enjoy some unfair advantages over Western competitors. But it’s false to think Chinese firms could or would want to supplant Western innovation everywhere.

The irony is that U.S. policy actions such as placing Huawei on the Commerce Department’s Entity List will force Chinese companies down a different road: designing out U.S. semiconductors and developing viable alternatives to existing options like Android. That will be an expensive an inefficient process – and not just for China: a long-term technology rift would also put revenue of leading U.S. tech suppliers at risk, sapping the funds available for the next generation of innovation.

Beijing can talk up its desire for dominance and self-sufficiency all it wants. The global success of Chinese tech firms will depend much more on individual companies’ ability to anticipate and respond to constantly evolving and market-driven customer demands, technology trends, and the actions of competitors. Indeed, the more complex and interconnected and global the technology ecosystem, the less successful governments are likely to be in directing technology development. And in the case of Chinese global players, more government involvement is more likely to hinder their efforts to compete.

Western policymakers should have more faith in the system that has gotten them this far; instead, they are acting as though China is 800 feet tall. History suggests that when a country ascribes superpowers to its adversaries, policy mistakes tend to follow.

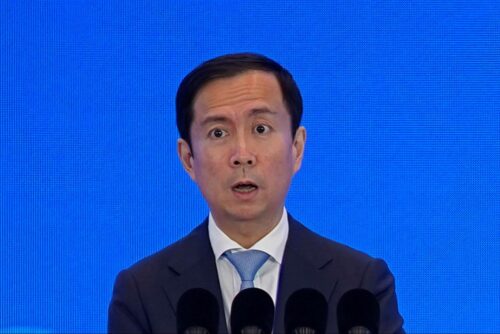

With contributions by Kevin Allison, Director of Geo-Technology, Eurasia Group. Top image via Bloomberg.