A Xinjiang scholar’s close reading of the China Cables

“Never allow escapes, never allow trouble, never allow attacks on staff, never allow abnormal deaths…”

Darren Byler analyzes the 25 key points in the Chinese government’s operations manual for Xinjiang’s detention camps.

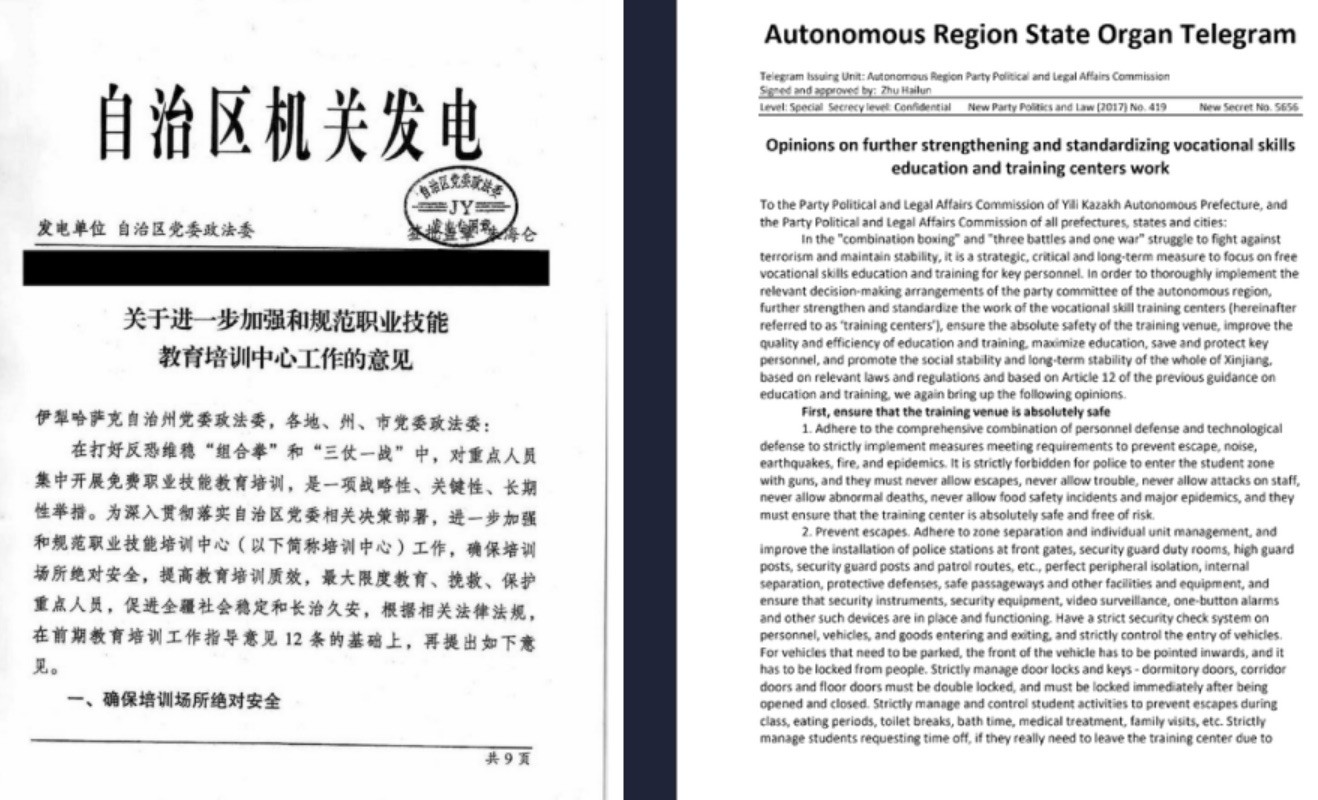

On November 24, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), led by Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian, published a 2017 classified directive issued by Zhū Hǎilún 朱海仑, the head of the Political and Legal Affairs Commission, the leading security administration of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Like the internal documents which had been published by the New York Times a week earlier, the “China Cables” show how the “reeducation camp” system is designed and orchestrated by authorities at the center of Chinese political power.

The China Cables corroborate many of the details provided by former detainees. For instance, they show that the use of coercive force and punishment is encouraged by the administration, and that those in leadership understand there are problems with food and disease due to overcrowding. The cables also show that assigned labor was always a goal of the reeducation system (see September’s column, How companies profit from forced labor in Xinjiang) and that they understood that their massive abuse of power demanded extreme levels of secrecy.

In what follows I will highlight what I see as the key aspects of all 25 points outlined by Zhu in the pages of the directive that have been recovered by the ICIJ. The full text of the English translation is here, and here is the Chinese original.

1. No abnormal deaths. The document begins with instructions to camp workers regarding the use of lethal force inside what it refers to as Vocational Skills and Education Training Centers. Zhu writes, “It is strictly forbidden for police to enter the student zone with guns.” This framing indicates that guns are used inside the camp facilities, but that they are not permitted inside detainee cells or beyond the barriers that separated camp workers from detainees in training facilities.

Continuing, Zhu notes that camp workers “must never allow escapes, never allow trouble, never allow attacks on staff, never allow abnormal deaths.” This phrasing indicates that if there are deaths within the center, that they should be presented as deaths by “natural causes.” It is also important to note that there are only prohibitions on detainees striking camp workers, there is no mention of restrictions on force used by camp workers toward detainees, a theme that emerges again later in the document.

2. Preventing escapes. Zhu goes into a great deal of detail regarding the mechanics of what is clearly a form of prison management within the Vocational Skills and Education Training Centers. For instance, Zhu writes: “Strictly manage door locks and keys — dormitory doors, corridor doors and floor doors must be double locked, and must be locked immediately after being opened and closed.” He goes on to note that detainees must be strictly monitored and controlled during “class, eating periods, toilet breaks, bath time” — an invasion of privacy that former detainees noted as particularly traumatizing.

3. Preventing “trouble,” Zhu suggests, starts by asking detainees to inform on each other in order to “prevent people from joining forces.” Importantly, Zhu further notes that preventing trouble means preventing detainees from having contact with “the outside world apart from during prescribed activities” — this demonstrates that the guided visits to camps which have been permitted for invited journalists and diplomats are highly unusual. In addition, Zhu writes that detainees are not permitted to have cell phones or use staff cell phones. In order to ensure that this is the case, the space of the Center must be “free of blind spots” in video surveillance, something that is noted in many of the bidding contracts analyzed by Adrian Zenz and others.

4. Problems with camp construction. Zhu notes that it is important that the construction of the facilities be earthquake resistant. This point of emphasis perhaps reflects standard talking points in government mandated construction, following the Wenzhou earthquake in 2008, but it could also be an indication that many of the facilities used as camps are in conditions of disrepair, as numerous former detainees have noted.

5. The threat of fires. In a continuation of the standard talking points regarding natural disasters, Zhu notes the importance of fire prevention. It is also important to note that a major point of emphasis in the People’s War on Terror more generally is controlling Uyghur access to flammable materials and reporting all instances of suspicious uses of gas or electricity. Zhu may have been particularly worried about the potential for arson in the context of the camps.

6. Overcrowding in the camps. Preventing epidemics in camps with populations exceeding 1,000 is a particular point of emphasis. Zhu noted the potential for the spread of influenza, typhoid, and tuberculosis, among other infectious diseases. He also writes in detail about the need to ensure food safety. These concerns demonstrate that Zhu had reason to believe that conditions of overcrowding and poor food quality could result in “abnormal deaths” — a point that is confirmed by numerous accounts from former detainees.

7. Closing off loopholes in the broader community. The task of carrying out these directives extended beyond the camp itself and into the surrounding community. All “loopholes” had to be blocked and emergency response plans had to be strictly followed.

In the next section Zhu describes the implementation and enforcement of the reeducation curriculum inside the camp.

8. The importance of the national language. Zhu turns to the implementation of the education program itself. He notes that the “three studies” — the “national language” (国语 guóyǔ, a term that is used to replace the term 汉语 hànyǔ, or the language of the Han), legal prohibitions, and skills development — should be at the center of the system. He notes that “the national language should be gradually used in daily life to communicate” — confirming that the use of Uyghur language gradually came to be prohibited inside the camp space. He also confirms that much of the instruction should be done using a “video education model” of projecting lectures onto monitors inside the camp.

9. No deviation from centralized curriculum. He also emphasizes that the curriculum should be centralized to ensure that there is no deviation in what is taught to detainees. He also notes that detainees with good language skills can be assigned to act as instructors for other detainees, confirming that camp instructors often also have quite limited forms of power and freedom.

10. The supremacy of standardized tests. Zhu notes that standardized tests should be used as the primary basis of evaluation of detainee progress within the camp system — a point that likely makes progress quite difficult for many detainees who have limited levels of literacy in both Uyghur and Chinese.

11. The role of psychological pressure. Ideological education focuses on guiding detainees “away from bad emotions.” In order to do this, detainees are asked to participate in public “repentance and confession” activities that promoted the “deep understanding” of their past “illegal, criminal and dangerous” behavior. Here Zhu notes that “psychological correction education” should be brought into play. He indicates that forms of public shaming should be used to trigger remorse and foster correct beliefs. This approach echoes numerous accounts of detainees and the analysis of scholars such as Timothy Grose.

12. The importance of Han cultural practices and industrial discipline. Another aspect of the camp reeducation system is an emphasis on Han cultural practices and industrial discipline. Zhu directs camp workers to “take the cultivation of manners as an important part of educational transformation and establish a strict life management education system.” This includes a focus on cultural performances of civility and courtesy, as well as new forms of submission, behavior, and habits. He also notes that people should receive regular haircuts, an order that explains why many detainees, both men and women, report that their hair was shaved. Zhu fails to note, however, that the conditions of overcrowding and surveillance in bathing and toileting stood in direct contradiction to his earlier mandate to emphasize personal hygiene.

13. Using family members to discipline each other. Zhu also directed camp workers to focus on reeducating the family members of detainees through the establishment of a “two-way point system.” This system, as outlined in the documents released by the New York Times, makes the release of detainees contingent on the behavior of the detainee’s relatives back in their home villages. Complaining about the disappearance of their loved ones can have a negative effect on the progress of detainees.

14. Progression through the system. In another confirmation of former detainee accounts, Zhu notes that there should be “three management areas” within the camps that detainees move through as they progress through the system. He also confirms that when detainees leave a facility their information must be entered into the Integrated Joint Operations Platform, which monitors movement through biometric checkpoints across the region.

15. Using technology and infrastructure to shape detainee life. Detainee life “should be formulated in detail.” They should have “a fixed bed position, fixed queue position, fixed classroom seat, and fixed station during skills work.” Because detainees are fixed in place, they can always be tracked and accounted for. Furthermore, Zhu notes that by standardizing processes of “going to the toilet, organizing and housekeeping, eating, studying, sleeping, closing the door and so forth,” students will increase their self-discipline. Importantly Zhu directs camp workers to “increase the discipline and punishment of behavioral violations.” This directive recalls the first point in this document, in which Zhu forbids detainees from striking camp workers. The same standard is not applied to camp workers. In fact, Zhu appears to explicitly encourage the abuse of detainees, something that has been reported in nearly all former detainee accounts.

16. Using reward and punishment to force transformation. Zhu directs camp workers to link the point system “directly to rewards, punishments, and family visits.” This he argues will encourage them to “truly transform” themselves.

The next section of the document reviews the standards used for transferring detainees into other forms of reeducation.

17. Must stay for one year. An important aspect of the directive has to do with what Zhu describes as “conditions for completion.” He writes that completion must be premised on the “lightness” of the pre-criminal behavior, a stay of at least one year in the camp, that they have been moved into the “general management area,” that they have completed all aspects of the transformation, and that there are no other extenuating circumstances.

18. The role of human supervisors and a “public security ‘integrated’ (IJOP) platform system” in the transfer process. In order for all of these criteria to be met, each detainee must be evaluated by a detainee “evaluation team” and the Integrated Joint Operations Platform. If no new problems are discovered through both the human and signals intelligence systems, the detainee can be recommended for transfer to the county-level Vocational Skills Education and Training Services Bureau for further evaluation by a leading group, who can then recommend evaluation at the prefecture level, where in consultation with local officials at the detainee’s place of household registration it will be determined where they should be assigned to work.

19. Coercive labor. Zhu notes that it is mandatory that all detainees be sent for skills training for three to six months. This training should be based on a combination of the detainee’s aspirations and, importantly, “the needs of society.” This second phrase is a nod to the coercive nature of work assignment for Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang. As Adrian Zenz has written, nearly all forms of Turkic Muslim labor has now become coercive. Although in some cases, the detainees welcome the greater levels of freedom that come from factory work and the minimum wage salaries they receive, in very few cases are they able to refuse to work in the place they are assigned.

20. The collateral damage of the reeducation system. Zhu directs prefecture and county-level camp workers to formulate resettlement plans to ensure the “smooth employment” of detainees. He notes, however, that assistance should be given to those “who don’t have the ability to work and have difficulties in life.” It is not entirely clear who he is referring to here, but it likely includes the elderly, infirm, and those that have been harmed mentally and physically by the camp system.

21. A minimum of one year of surveillance of transferred detainees. It is important to follow up on the progress of detainees as they are transferred into other parts of the reeducation system. Zhu writes that police stations and the judicial offices should not allow detainees to leave their “line of sight for one year,” and their performance should be evaluated in a timely manner. “Not even one person should leak out.”

The final section of the document describes the role of organizational structure in the camp system.

22. Reeducation system includes all government departments. The system should include the cooperation of “the public security, judicial, education, health departments and so on…as a common force.”

23. Requires total loyalty. In order to accomplish this, Zhu suggests, “We will arrange to have the strongest leaders, the strongest cadres, and the strongest security forces in the training center.” By strongest he means those who are “politically strong, brave in action, committed and dedicated, and have an excellent work style.” Those who are of lower quality will be replaced.

24. Requires that problems with food and construction be addressed. These forms of human quality will allow camp workers to “strictly implement the standards for student meals, speed up the construction and renovation of sites,” suggesting again that he had concerns regarding the distribution of food and quality of facilities.

25. Requires total secrecy. The final point included in the document is the need for “strict secrecy.” Zhu writes unequivocally that the work of the camps is “highly sensitive.” Continuing, he notes, “It is necessary to strengthen the staff’s awareness of staying secret, serious political discipline and secrecy discipline. It is strictly forbidden to bring video and video equipment such as mobile phones and cameras into the teaching and management areas and uploading pictures onto the internet at will. Relevant important data should not be aggregated, not be disseminated, and not be open to the outside.”

Reading through this document, it is clear that Zhu Hailun thought deeply about how to “round up those who needed to be rounded up,” as Chén Quánguó 陈全国 had ordered. The callous way with which he authorized discipline and punishment of detainees can be read as a direct manifestation of Xi Jinping’s directive to show “absolutely no mercy.”

There is something unusually cruel about Zhu Hailun. Unlike Xi Jinping or Chen Quanguo, he grew up surrounded by Uyghurs and learned to speak Uyghur like a native. Based on the interviews I have done with many Xinjiang Han people over the years that I lived in Xinjiang, I would have assumed that he would have a certain sympathy for the people from his home community. Typically, those who identify as native to Xinjiang see the attitudes of Uyghurs as a product, at least in part, of the forms of dispossession and state violence that has confronted them over the past several decades. Zhu seems to see none of that. Instead, he is using his intimate knowledge of Uyghur society to inflict as much damage as possible to its last remaining institutions. He is using family members against each other, mandating the criminalization of Uyghur language, violating individual privacy by directing the surveillance of toileting and bathing, and authorizing psychological and physical trauma against detainees in order to force them to “deeply understand” that practicing Islam is a “dangerous crime.”

Darren Byler’s Xinjiang Column is published on the first Wednesday of every month. Previously:

Ilham Tohti’s Sakharov Prize and the desecration of Uyghur society