U.S. House passes Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act of 2019

The aim of the bill is “to address gross violations of universally recognized human rights, including the mass internment of over 1,000,000 Uyghurs.”

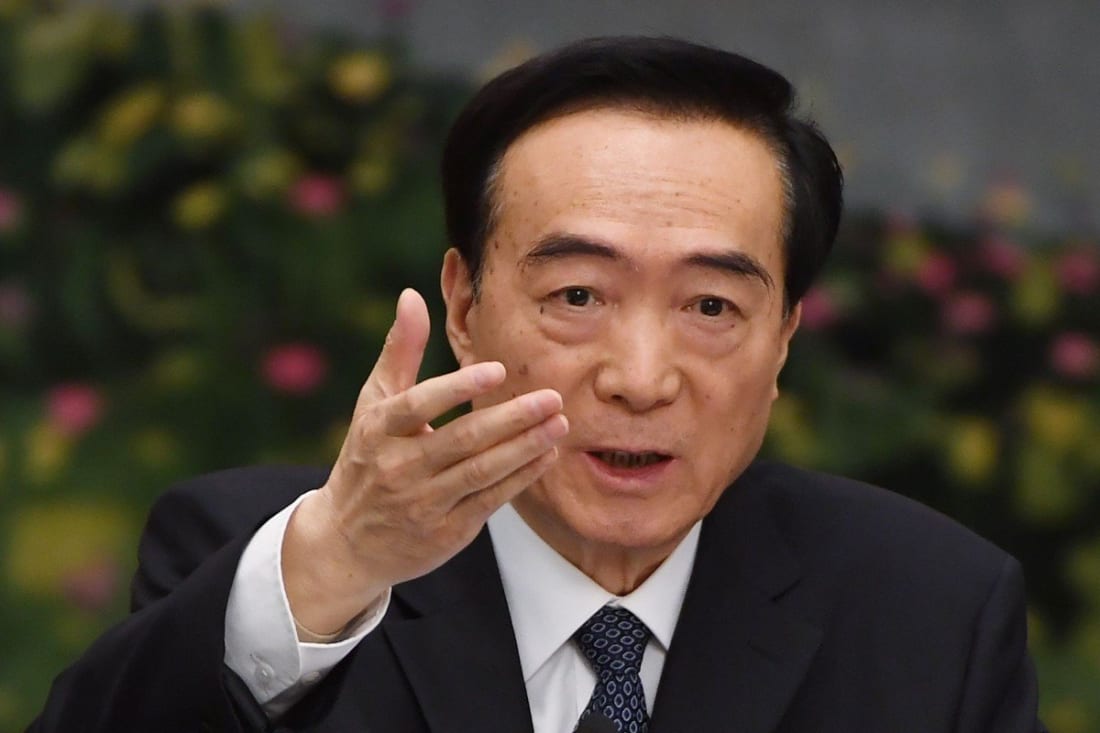

Chén Quánguó 陈全国, Party secretary of Xinjiang, is named as a target of sanctions in the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act of 2019. Image: AFP.

The U.S. House of Representatives on Tuesday passed a bill by 407 to 1 called the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act of 2019. The bill, a stronger version of legislation that passed the Senate in September, still needs approval from the Senate and a signature from the president to become law.

What’s in the bill?

The aim of the bill is “to address gross violations of universally recognized human rights, including the mass internment of over 1,000,000 Uyghurs.”

It accuses China of “systematically discriminating” against Uyghurs by “denying them a range of civil and political rights, including the freedoms of expression, religion, movement and a fair trial,” and details abuses that have been documented in Xinjiang, including pervasive surveillance, DNA sample collection, and extensive use of facial and voice recognition software and “predictive policing” databases.

The bill calls for “targeted sanctions” on members of the Chinese government responsible for the atrocities in Xinjiang, and specifically names the region’s Communist Party secretary, Chén Quánguó 陈全国.

The bill includes stricter export controls on U.S. technology that could be used to “suppress individual privacy, freedom of movement and other basic human rights” in Xinjiang.

The bill’s passage comes just four days after Donald Trump signed the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act of 2019.

Now this, just in from Axios:

Senate Finance Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley has requested a meeting with the World Bank over a $50 million loan approved for China’s Xinjiang region, where upwards of one million ethnic minorities have been detained, in a letter obtained exclusively by Axios.

How did China react?

With anger, of course:

Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Qín Gāng 秦刚 yesterday “summoned William Klein, acting deputy chief of the Mission of the U.S. Embassy in China, to lodge stern representation and strong protest” against the passing of the bill, reports Xinhua. Qin promised vague retaliation: “China will respond further according to the development of the situation,” he said.

State media spat out a series of editorials condemning the bill. Here’s a taste from Xinhua: Meddlesome Washington’s malicious farce on Xinjiang, and in Chinese, Using Xinjiang to control China is a plot that will never succeed.

Fighting terrorism is Beijing’s main line of defense. One Xinhua article (in Chinese) based on Foreign Ministry statements says “9-11 was not long ago,” and that the United States should not “forget the pain” or “play with double standards on counter-terrorism.”

Another article (in Chinese) describes a press conference held in Kabul by China’s ambassador to Afghanistan to condemn the bill and persuade local journalists that China “has established education centers in accordance with the law to educate people affected by extremist ideology or who have tendencies to commit minor crimes, help them to correct extremist ideology, impart professional skills for free, and enhance their reemployment and livelihood capabilities.”

What will China do next?

Beijing does not appear to have a lot of options.

“Foreign ministry spokeswoman Huà Chūnyíng 华春莹 said the latest bill on Xinjiang would ‘inflict some costs’ and have an impact on China-US ties and ‘cooperation in key areas,’” reports the South China Morning Post:

“A lot of people have issues with the US’ hegemonic acts and stupid behaviour and have floated ideas for us… As to what action China will take, I think you can wait. The costs will come sooner or later,” she said, without elaborating.

“Postponing trade talks and targeting American companies” are two “tough” responses also being considered, according to unnamed Chinese government advisers cited by the SCMP.

The editor of propaganda sheet Global Times Hú Xījìn 胡锡进, who often says the quiet part out loud, posted two tweets about the bill:

The bill is a paper tiger with no special leverage that could affect Xinjiang. Xinjiang officials, including the Party chief Chen Quanguo will look at ‘sanction’ with scorn because they have no connection with the U.S. But U.S. politicians with stakes in China should be careful.

Based on what I know, since U.S. Congress plans to pass Xinjiang-related bill, China is considering to impose visa restrictions on U.S. officials and lawmakers who’ve had odious performance on Xinjiang issue; it might also ban all U.S. diplomatic passport holders from entering Xinjiang.

Context

Here are three relevant pieces published yesterday. It’s worth noting that mainstream Western media is getting more comfortable with the use of words such as genocide and concentration camp.

Recently accused of working for “the U.S. intelligence agency” by state media, The China Project’s Xinjiang columnist, Darren Byler, has written an analysis of the leaked Xinjiang materials: A Xinjiang scholar’s close reading of the China Cables.

The government is struggling to retain cadres in Xinjiang because it is so unpleasant working there, according to the South China Morning Post:

The measures targeting Muslim ethnic minorities in Xinjiang have triggered “widespread discontent among Han Chinese officials and citizens,” a source close to the central government told the South China Morning Post. The source said Chinese President Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 was aware of the problem because he had been briefed by the country’s chief Xinjiang policy coordinator, Wāng Yáng 汪洋.

“China’s Uyghur genocide must be put on trial” is the title of a Foreign Policy piece (porous paywall) by Azeem Ibrahim, a research professor at the Strategic Studies Institute at the U.S. Army War College. He argues that the Xinjiang leaks to the New York Times and the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists leave “the international community with an unambiguous moral duty to intervene.” His suggestion is to begin with “an investigation led by the International Criminal Court.”