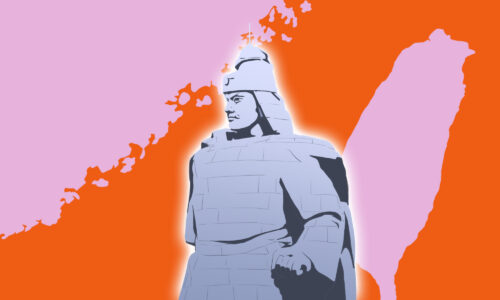

How China’s ‘century of humiliation’ resonates today

This week’s column comes from one of Kaiser’s answers originally posted to Quora on September 7, 2016:

What lesson did Chinese people learn from the “hundred year humiliation”?

Rightly or wrongly, the primary lessons learned by Chinese state actors — and to an extent I think this is true of the Chinese people more generally — were that wealth and power are paramount goals, that weakness and technological backwardness are fatal, and that no one will hesitate to exploit weak states. Only strength and wealth can earn a nation respect and preserve sovereignty. National strength requires unsentimental assessment of national characteristics, and the extirpation of those traits that make a nation weak. Tradition is only valuable if it serves the ends of national wealth and power. Unity — or at least presenting a convincing façade thereof — is necessary. A ruthless pragmatism, a defensiveness about anything that infringes on national sovereignty, a prickly intolerance for anything that smacks of separatism — these are all things that China learned from its “century of humiliation.”

Also see:

Kuora: The Opium Wars and China’s Century of National Humiliation

There are Chinese people today who believe that the Chinese Communist Party has cynically perpetuated the humiliation narrative for its own ends, and there are Chinese people who say they honestly feel it even today, though born many decades since it came to an end in the middle of the last century. But there are very few, I think, who would dispute the basics of the narrative: that China, once a proud, wealthy, and powerful empire with an immensely rich heritage of art and literature, was brought low and humiliated by more technologically advanced powers. Whether they lay the blame more at the feet of complacent rulers, effete bannermen, their own civilizational arrogance, or the rapacity of the imperialist powers, they all would agree that China’s sense of itself was completely upended, its grandeur despoiled, and its very existence imperiled.

We’ve come now to think of this idea of a “national humiliation” as a narrative owned by the Communist Party, but we’d do well to remember that it was felt keenly by pretty much any intellectual of the modern era who cared a fig for the fate of his or her nation. Chiang Kai-shek wrote the words avenge humiliation on every page of his diary for 20 years. If you fail to grasp how central humiliation was to the whole story of modern China, you’ll never really understand China today on its own terms.

Kuora is a weekly column.