According to the nonprofit anti-trafficking organization Polaris Project, there were more than 9,000 illicit massage parlors in the United States in 2017, mostly staffed by Chinese women, aged 35-55, with at least one child in China. Their struggle is often one for family and dignity. Here is one woman’s story.

The building that houses Queens Criminal Court, like the city of New York itself, is usually filled with a mixture of men and women of all ages and races. But when I went downstairs to courtroom AP-8 one morning last April, I found myself facing a group of 25 women, mostly Chinese.

The Chinese women looked plain. They had no makeup. Half of them were over 40. The oldest was 52 years old. She wore an earth-colored woolen coat. She was hunched and short, with an honest-looking face, resembling a grandma who had just returned from farm labor.

The other women in the room — white, black, and Latina — were completely different: They were dressed flamboyantly, with showy nail polish and lipstick. One was even wearing a large brimmed pirate’s hat.

But all of the defendants were here on the same charge: prostitution.

Illicit massages in America — a $2.5 billion industry

If I had not read their charging documents, I would never have guessed that these matronly Chinese women were accused of being involved in the sex trade. But as I learned over the subsequent months, low-profile Chinese women of humble origins and modest appearance are the backbone of the illicit massage industry in the U.S., which generates $2.5 billion revenue annually. Many of these women are mothers who left home to support their families, arriving in the United States without the faintest idea of what they would do to make their American dream come true.

For many Americans, their awareness of Chinese massage workers in America begins and ends with Robert Kraft, the New England Patriots owner whose visits to Orchids of Asia Day Spa were made public after a police sting early last year. Kraft was only one of hundreds of people implicated, but his status in the sports world brought national attention to the case. Unfortunately, in much of the reporting, the women were an afterthought, while police struggled to acknowledge, as Vanity Fair wrote last month, “that immigrant women of precarious status, hemmed in by circumstance, might choose sex work.”

According to the nonprofit anti-trafficking organization Polaris Project, there were more than 9,000 illicit massage parlors in the United States in 2017, mostly staffed by Chinese women, aged 35-55, with at least one child. You can find them in strip malls, apartment buildings, office towers, and suburban houses. Most of the parlors use “SPA” or “Massage” in their names, added to Angels, Asian, Jade, Good Girl, or some other suggestive word.

You can get a non-sexual massage in these places, but that’s not how they make their money.

My way into the hidden world of illicit massage was through the American Chinese newspaper World Journal (世界日報 shìjiè rìbào, the largest Chinese-language newspaper in the U.S., with a stated daily circulation of 350,000). Every day, the newspaper’s print version carries two or more pages of classified advertisements in the “massage” section. Each ad has a phone number and a short description. Some are more subtle, like “Little sister student,” or “Fresh from Fujian.” Others make their services a little more obvious: “Huge breasts — just arrived from Nanjing.”

As I would learn, these ads are a key channel for many women working in the illicit massage industry. Some advertise for themselves and work solo. But many ads are placed by massage parlors, and by telephonic pimps who set up massage sessions for a commission. I tried to call nearly a hundred of these phone numbers to find someone who was willing to talk to me about their work. Sometimes I was greeted with swearing, or a desperate warning, like: “Do not send me any messages, my husband and children will see them,” or “I’m going back to China, no interviews.” Some of the women who picked up the phone made panicky noises, and then said “wrong number” before hanging up. Some of them hung up as soon as I said the word “reporter.”

One woman spoke to me for about 10 minutes about her numbness in running the business. I spoke to two women who ran massage parlors who agreed to give me a job interview near the main street in Flushing, but I figured it could be complicated to show up. None of the women working in the business were willing to meet me for an interview.

But finally, I got a hold of Lisa. “Or Tina or Rose or Guìhuā 桂花 — call me whatever you want.” A few days after we’d arranged to meet, this woman from northern China blew into her chosen restaurant like a gusting red whirlwind. It was a very old American diner in a neighborhood of Queens where there are very few Chinese people. We were the only Asians in the restaurant, and could talk freely in Mandarin.

Lisa uses a pseudonym, like all Chinese illicit massage workers. The tender Chinese names their families used to call them — Juan, Mei, Yan, Yi, or Fei — that connote grace, nobility, and virtue are buried deep. Now they are Nancy, Linda, Tina, Lulu, and Cici.

Let’s call her Lisa.

Lisa is quite beautiful and has a capable, self-assured air. Although she is over 50 years old, she looks 40. Originally from northern China, she is now the owner of two illicit massage parlors in the New York area with 13 workers.

Her business has been very successful. From the moment she took her seat, her two iPhones constantly rang and buzzed with WeChat messages. The harsh wind of a New York April was still blowing, but Lisa was sweating as she took a call, juggling between that and a barrage of messages from her other phone.

“I understand her, but she really shouldn’t have done it.”

There seemed to be a dispute between a client and a massage worker.

“You should also understand her, but [you’re right], she really shouldn’t take on another client.” Lisa tried her best to fix the relationship between her massage worker and the angry customer, in fluent English.

The customer ranted at Lisa for several minutes. Then she said: “Good, good, I promise you that this won’t happen again.”

After apologizing several more times, Lisa finally put down her phone. She explained that the massage worker had only given the customer half an hour instead of the one hour agreed upon, and drove him away because the next customer was arriving. Lisa explained, “This woman is too eager for quick success. But women in this business need to be smart, and only by giving enough time can they earn money.”

Lisa clearly likes to repeat the phrase “women in this business need to be smart.” She said that some women received clients at hotels and earned a lot of cash by the end of the day. But at night, some clients would come in, smash the woman’s head against the wall, and demand cash at gunpoint. “A smart woman would give the robber her cash and her body, then all will be fine. Otherwise, she will lose her life.” Lisa said robberies like this happen to them every single day. However, these women, even when they’re assaulted, dare not call 911.

I didn’t understand why Lisa — who was so proud of her survival instincts — would take the risk to talk to me. I asked if she ever worried I could be an undercover agent. She said no.

I thought, OK, she’s smart, smart women understand the world as it really is, and always know what they want. But that’s not why I think she took the interview. It took me four hours of conversation with Lisa to figure out why she came to meet me that day in that old diner.

How a Chinese factory worker gets a U.S. business visa

In 2007, Lisa was an ordinary worker in a failing state-owned textile factory in China. At the time, she earned $100 a month and lived a desperate, hopeless life. Her husband died of a disease — she didn’t say what — and she was left to raise her son alone. Seeing her son growing up each day, she felt impotent because of her poverty: “What if he is admitted to college, but I can’t afford the tuition? Do you understand this pain?” she asked me.

But what triggered her decision to revolt was her inability to get a factory-allocated apartment, as she and her fellow workers had anticipated. “The leadership had taken away most of the housing without shame. Ordinary workers like me couldn’t get one at all. People of our age were very willing to work for our country. However, the reality made me question the education I had received for so many years. Aren’t Communist Party members supposed to think for the people? I was very disappointed. I wanted to change my fate and my son’s.”

What China couldn’t provide, Lisa turned her gaze to the United States to find.

She didn’t care how, as long as she could go. She paid $17,000 to an agency in Beijing to secure her a business visa. All the paperwork was fake. She, along with some street cleaners, were all packaged as sales managers from large enterprises. On the day of the appointment with the visa officer, Lisa walked into the U.S. embassy wearing exquisite makeup and a suit, pretending to be a successful businesswoman.

“It was blind luck,” she explained. “If the visa officer had asked me a few more questions, I would have been caught, but every industry has its loopholes.” When the visa officer handed her a piece of paper, Lisa began crying: “It wasn’t joy, I did not want to leave my beloved homeland.”

Twelve years later, talking about that moment with me, her face started to tremble again. She covered her eyes with a napkin and began crying uncontrollably: “For so many years, whenever I think of this scene, my tears could not stop…”

I asked what it felt like to leave her son behind. All she would say was: “My son was still very young, then only a teenager.”

“Study hard, Mom will come take you to the U.S. later.”

After getting her visa, she got on the train to her hometown in Hebei province, and cried all the way home. Then she began preparing her son for her departure: “Study hard, Mom will come take you to the U.S. later.”

Lisa’s plane landed in New York in 2007.

A friend of an internet friend of Lisa’s had arranged for her to stay at a Chinese-run family hotel in Flushing that cost $10 a night. A spiral staircase led deep down to her room in a dingy basement. Next to the room, four shirtless men were playing mahjong and smoking. She didn’t know what kind of darkness these stairs would lead to. Lisa was terrified and hesitated at the top of the stairs. The friend of a friend asked: “So you can afford the $100 hotel outside?”

She finally took the first step. She trembled as she passed the shirtless men, with their foul smoke. She entered a small room with four bunk beds, right next to the noisy mahjong players clacking their tiles on the table.

During the night, someone asked Lisa, “Why are you crying?”

She did not answer.

She cried the whole night.

Since the 1990s, Flushing in Queens has been the first destination in New York for many Chinese immigrants. Some of them say they don’t feel like they are abroad in Flushing. You hear all kinds of Chinese dialects on the street, but most people speak Mandarin. The food smells like China: Northeastern fried pork, Fujian bean curd, Cantonese roasted pork, Taiwanese salty fried chicken, Chongqing spicy noodles, Shanghai steamed buns, and Tianjin meat pies.

Stores and street vendors also use the Chinese style of prolonged shouts to hawk their wares. If the buildings and subway were removed, and hawkers and pedestrians were wearing ancient costumes, Flushing could be the China of 500 years ago…until the unique Flushing shouts of “learning English,” “Green Card and Citizenship Application,” “Quit the Communist Party of China for Blessings” drag you back to reality.

But this wild vitality betrays the hardships that many of the residents of Flushing face. Many left China penniless: they are poor villagers from the south, laid-off workers from the north, and bankrupted business owners from all over the country. They all come to America to get just one thing: money.

Lisa started looking for a job the day after landing. She applied for a position as a typist, but was dismissed as too slow; and for a position as a babysitter at a house 15 hours’ drive away from New York, which she dared not go to. Then she found work at an above-board massage shop in a mall somewhere a few hours’ drive away from New York. Lisa never knew where exactly, because she understood virtually no English. She simply hopped on a bus she’d been told to take, and voilà, she was there. But then she found that everyone at the shop was busy making money for themselves giving massages, and no one took time to teach her the skills she needed. She still needed to pay for accommodation but wasn’t making any money, so Lisa decided to return to New York.

She resumed her job search. While loitering in the street one day, someone grabbed her and said, “Miss, you are so pretty, do you want to receive a facial?”

“I don’t even have a job; how can I have the money to get a facial?” she answered.

“Well, I can find you a job.”

She was led to a shop near a subway exit. To her surprise, it was a massage parlor again. But this time Lisa, who knew nothing about massage, just pretended she knew what she was doing. She followed one simple rule: Just rub. “I press wherever the customer points, and I also press wherever my boss points.” The business was booming and no one cared about specific massage skills.

At first, Lisa was happy. But the work soon ground her down: nine to ten hours a day with only 10 minutes for a lunch break, seven days a week. Although she earned $150 a day, she had no time to spend it, or do anything else. Lisa, a lover of fine things despite her humble origins, said, “There was not even time to buy clothes. It was just like prison. People should have their own time.”

Lisa didn’t just want money, she also wanted freedom.

Lisa began to observe American society. She said she believed that every country has its loopholes, like the one she had jumped through when she received her U.S. visa. When her former bosses warned her that the police would take her away if she “let a customer turn over during the massage,” Lisa learned that there is only one turn of the body between an illicit massage and a legal one.

She changed her job.

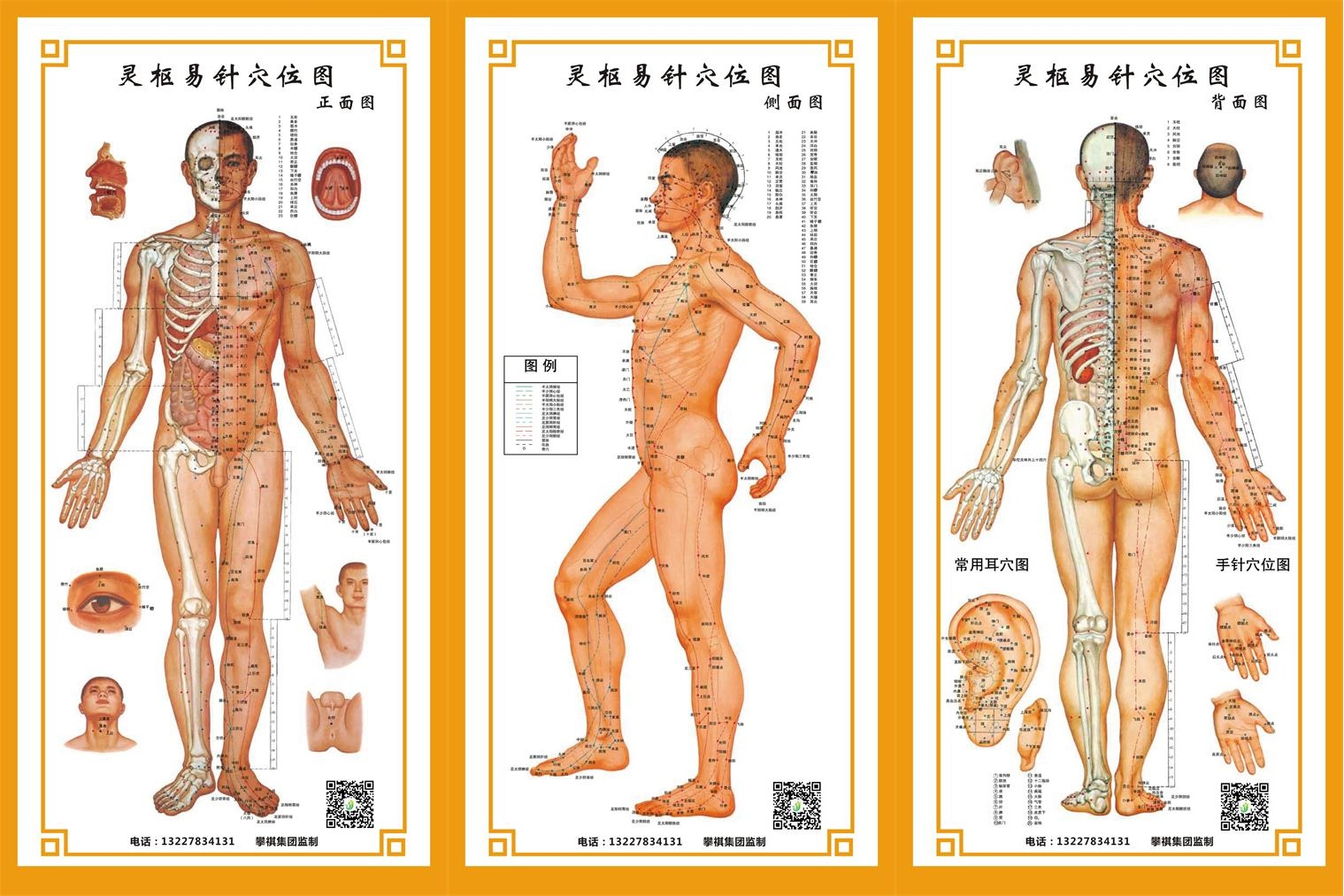

China’s second great cultural import

In 2007, when Lisa arrived in New York, it had only been four years since the Chinese acupoint massage had taken off in the United States. Acupoint massage, also known as acupressure, uses the same meridian system as acupuncture, and many believe it is an effective therapy for various ailments. Even if you don’t believe in the medical benefits, acupoint massage just feels good.

In 2003, large numbers of Chinese people living in Flushing began taking the subway to Central Park, where they would set up fold-up chairs and offer acupoint massages to passersby. They charged a dollar per minute, 10 minutes per session. Americans would often give a 20- to 50-percent tip, so it was common to earn $12 an hour. Minimum wage was $5.15 an hour in New York that year.

Americans loved the traditional Chinese acupoint massage technique. They loved the way it felt, and it had a mystique that fit perfectly with growing American interest in “alternative medicine.” Although the massage business in Central Park was eventually banned because it became too big, some of the massage workers opened shops in malls, office buildings, and in regular store fronts.

Thus, massage therapy became the second Chinese cultural import, after Chinese cuisine, to really catch fire in the United States. But Chinese massage therapy has a much less salubrious image than Chinese cuisine, because it involves skin-to-skin contact.

Massage customers in shops in malls wanted privacy, so the shops began providing curtains, leaving the customer and massage therapist alone together. By 2007, many of the shops signed as acupoint therapy spas had begun offering massages that had no medical aim.

Lisa’s new workplace was one of these. She called it “a freestyle shop.” It was in a high-rise office building in Manhattan. The boss never showed up. There were only four employees. When customers came, whoever received them could do whatever they wanted.

Lisa said that her first customer grabbed her hand and pressed “there.”

“Did it involve sexual intercourse?” I asked.

“There were only curtains, so only by hand.” Her voice dropped, almost to a whisper, even though it was unlikely anyone in the American diner understood Chinese.

In this “hand job parlor,” Lisa received three or four clients a day, earning about $150 per day. Much easier than a regular massage parlor, where she saw nine to ten clients every day.

Lisa gets a green card, and her own massage parlor

Lisa was making money, but she began to worry about her legal status. “Every time I came across the big words ‘illegal immigrants’ in the newspaper, I was frightened,” she said.

So she got married to an American man 10 years her senior. This enabled her to apply for a green card, and Lisa saw it as the key to a great future.

Lisa says that it has become common for Chinese massage workers to obtain green cards by marrying Americans. Many of them barely speak English, so their communication with their husbands relies on mobile phone translation apps. Some are even forced into prostitution by their husbands after marriage. But for many, it’s worth the risk.

Lisa’s husband was her English practice partner in a coffeeshop. After a few meetups over the first three months of her stay in America, Lisa asked the man to help with her legal status. But the only thing he could do was to marry her. So he did.

They’re still married. Although she never tried to hide the pragmatic nature of their marriage, she repeatedly mentioned that her husband is a very kind person. He tried to add her name to his property, but she refused, saying, “I can make money myself, why should we be bound together?” Now, her husband is seriously ill, but Lisa stays by his side. She takes care of him until 1 pm every day and sends him to a care center before going to work.

After her marriage, Lisa resigned from the freestyle massage parlor. In order to keep her green card, Lisa was careful not to break the law. She wanted to open a regular massage parlor to make a living, but the plan didn’t go well.

“It’s very difficult to survive if others are involved in sex and I’m not,” Lisa told me. “Demand drives the business. And if the customers ask for sexual services, how is it illegal to charge one hundred dollars?”

When Lisa realized that “clear water feeds no fish” (水至清则无鱼 shuǐ zhì qīng zé wú yú ), she resigned herself to joining the illicit massage industry. Her husband warned her, “You can run a parlor, but you must not receive clients yourself.” So she set up shop as the boss. She answered the phone, advertised, and paid rent and fees. A dozen years later, Lisa has expanded her business from one parlor to two, and now she wants a third.

In many respects, her work is the same as any other small business owner. But there’s one aspect of running an illicit massage parlor has its own unique characteristics: the recruitment and retention of workers.

Human trafficking and voluntary labor

Lisa turned to the internet to recruit. She advertised in the employment pages of Chinese-language websites, using code words like “monthly income of $10,000” and “young and beautiful massage workers needed.”

According to Lisa, she never coerced any of her workers. They had, she said, all voluntarily come to the U.S. with clear life goals of supporting their family back home. Speaking of the industry in general, Lisa said that some sex workers came to the United States after an unprofitable journey to the Middle East; some came after the citywide campaign to eliminate prostitution in China’s “sex capital” Dongguan; a small number of international students also engage in sex work to earn tuition money; but many were in their 30s or 40s, and their only goal in coming to the United States was to improve the lives of their families in China.

I asked her why so many massage workers were from China. She said it was just numbers, and that makes sense: From 2000 to 2016 alone, the number of immigrants from mainland China to the United States increased from one million to two million. Lisa said the 10-year tourist visa, issued to Chinese citizens since 2014, made life much easier for those working illegally.

Lisa told me about one of her workers, a woman Lisa prefers to call Hong. She is in her 30s, “quite beautiful and hardworking.” Sometimes when customers call Lisa in the middle of the night, Hong gets up, receives the customer, and takes the job as seriously as any other professional would. “Sometimes this kind of dedication is very touching,” said Lisa.

Hong earns more than $30,000 a month, but she spends little on herself. She sends the money back home so her family can buy a house for her younger brother.

The massage worker I spoke to on the phone before meeting Lisa, who would not agree to meet me, also talked about family responsibilities: “Women at the bottom are very responsible, they shut up and earn money. Compared with the heartless NYU and Columbia masters and doctorate students, these women live honorably for their families.”

None of the women I spoke to said they had been forced into sex work. Some, like Lisa, might successfully navigate an inherently exploitative system, but she is perhaps the exception rather than the rule.

“A lot of women had no idea this was going to involve prostitution at first,” said Yvonne Chen, supervising program manager at Sanctuary for Families, a New York service provider for survivors of gender-related violence. Chen once handled a case in which a woman was arrested on prostitution charges. She told Chen that she had been raped at a massage parlor but didn’t tell anyone because she was worried about angering the boss.

Indeed, according to a 2017 report by the nonprofit anti-trafficking organization Polaris Project, “There may be women who choose to sell sex either along with or under the guise of massage therapy, but evidence suggests that many of the thousands of women engaging in commercial sex in illicit massage businesses (IMBs) or ‘massage parlors’ are victims of human trafficking.” The report says that while “it is not known exactly how many women working in massage parlors today are trafficked,” there is plenty of evidence to suggest it is widespread:

Every story is a little different but they all share a common pattern that combines fraud, threats and lies with poverty, fear and the potential for violence…

In 2017, Polaris analyzed more than 32,000 cases of human trafficking and developed a classification system that identifies 25 distinct types of human trafficking in the United States. Each one has its own business model, trafficker profiles, recruitment strategies, victim profiles, and methods of control that facilitate human trafficking. They all fall roughly into categories of sex trafficking, labor trafficking or a hybrid of the two — that is, venues that involve both sex and labor trafficking.

Trafficking related to illicit massage parlors accounted for 2,949 cases — second in prevalence only to trafficking in escort services. Most of the victims are women in their mid-thirties to late fifties from China and South Korea.

Additionally, most are mothers struggling to support their children. According to data from Restore NYC, 80 percent of the IMB survivors it has served have at least one child, and 84 percent of their children are overseas.

The Polaris Project report also offers recommendations for ending human trafficking in illicit massage businesses, but admits that the “complexity of human trafficking in all its forms belies the possibility of an easy solution.”

In fact, some sex worker activists are wary of anti-trafficking campaigns. Red Canary, which “supports the grassroots organizing of migrant sex workers, starting with the Chinese community of massage parlor workers in New York City,” published a report on the issue titled, How anti-trafficking investigations and policies harm migrant sex workers, with this motivation:

We witness the everyday reality of how migrant sex workers are harmed, and made vulnerable, as a direct result of anti-trafficking initiatives.

These initiatives are presented as necessary rescue and protection for migrant sex workers, but in fact, they encourage anti-migration attitudes, racism, and the criminalization and discrimination of sex work.

Red Canary’s slogans and hashtags include #RightsNotRaids and #SexWorkIsWork. They see decriminalization as an essential step in protecting their rights. Because even when massage workers are not victims of trafficking, the illegal status of their work makes them easy targets for all kinds of shady operators: Robbers stormed the shop at gunpoint; drivers charge them 10 times the market price for a ride from the airport to Flushing; crooked lawyers scam their money and suddenly disappear; customers refuse to pay; landlords give them trouble; police officers harass and rape them; the list goes on and on and on.

And now there’s a new issue they have to face: increasingly stringent licensing requirements to run any business offering massage.

New licensing requirements

The sudden emergence of the Chinese massage industry — both legitimate and illicit — was a blow to the American massage or “massage therapy” industry, as it prefers to be known. On the Yelp review website, a Chinese massage parlor (apparently a legitimate enterprise) is currently the top search result for “massage in New York,” while Massage Envy, the largest massage chain in the US, lingers beyond the 10th page of results, behind various apparently illicit massage businesses.

Illicit massage operations have long been a problem for above-the-board massage workers, but the effort to regulate illicit operations out of existence has intensified together with the growth of Chinese massage shops.

In 2006, as acupoint massage and Asian-themed massage parlors were booming in the U.S., the American Massage Therapy Association (AMTA) launched a campaign to lobby for “fair and consistent licensure in all U.S. states, to eventually achieve portability of practice between states.” Licensure and ongoing training professionalize the business, allowing service providers to charge more, and accept health insurance payouts. It also makes it more difficult to run an illicit massage parlor openly — someone actually has to know what they are doing and pass exams.

Currently, massage therapists need licenses in 43 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Licensure “must be renewed on a regular basis, with a majority of states requiring continuing education as a requirement for renewal,” according to Associated Bodywork and Massage Professionals.

In most states, massage therapist license exams are only offered in English and Spanish. I could not find a single example of a state that offered Chinese-language tests. The questions are becoming more and more difficult. In most states, the examination involves at least 10 highly specialized areas of knowledge, such as anatomy and physiology. Students may need to take full-time courses ranging from 6 to 12 months or equivalent part-time courses in order to even sit the exam.

Nonetheless, licensing requirements vary tremendously from state to state. And there are plenty of loopholes: In Ohio, for example, massage for medicinal purposes requires a therapist’s license, but there is no such demand for people who massage for other purposes such as “relaxation.”

Lisa became very angry when she talked about the new licensing requirements. At the beginning of the interview, she said, “I like America because it is fair to the working class.” Now she spat out: “China and America are the same in terms of interest conflicts. This is anti-Chinese.”

Lisa did not tell me if her two parlors were licensed, or what legal structure she used to operate. She’s a smart woman. She must have figured it out. Lisa has not been arrested once in her 12 years of work.

She seldom visits the parlors she operates, and is mainly responsible for answering calls on her cellphone. And even that tether to her business may soon be cut, she said, in an abundance of caution.

Lisa keeps her promise to her son

Our conversation meandered. Lisa mentioned to me that a male reporter had once contacted her and asked for an interview in exchange for $100. Lisa’s pride was wounded.

“One hundred dollars? I make a hundred dollars in 10 minutes. Articles written by such reporters are especially vile and debasing. People who write such articles are very dirty.”

Lisa saw hypocrisy everywhere. She repeatedly reminded me during the interview, “How come this industry has endured since ancient times? Why don’t the upper classes work in the industry? Why is it legal when government defines it legal, and illegal just when the government says it is?”

Her questions all seemed aimed at fighting the stigma attached to sex work. Having a chance to dispel these humiliations, I realized, was the real reason why Lisa accepted my interview. She wanted to tell her story from her point of view, in a position of dignity.

I asked her about her son again. She had not mentioned him since she described leaving China at the beginning of our interview. With a proud face, she said her son is now serving in the military in the United States.

“Does your son know about your job?” I asked.

“Yes, but he doesn’t ask much.”

“What kind of wife do you want your son to marry?”

“This is up to him.”

She left it at that, unwilling to talk further about her son.

Top illustration: Sebastian Dahlstrom for The China Project