In the spirit of Lei Feng

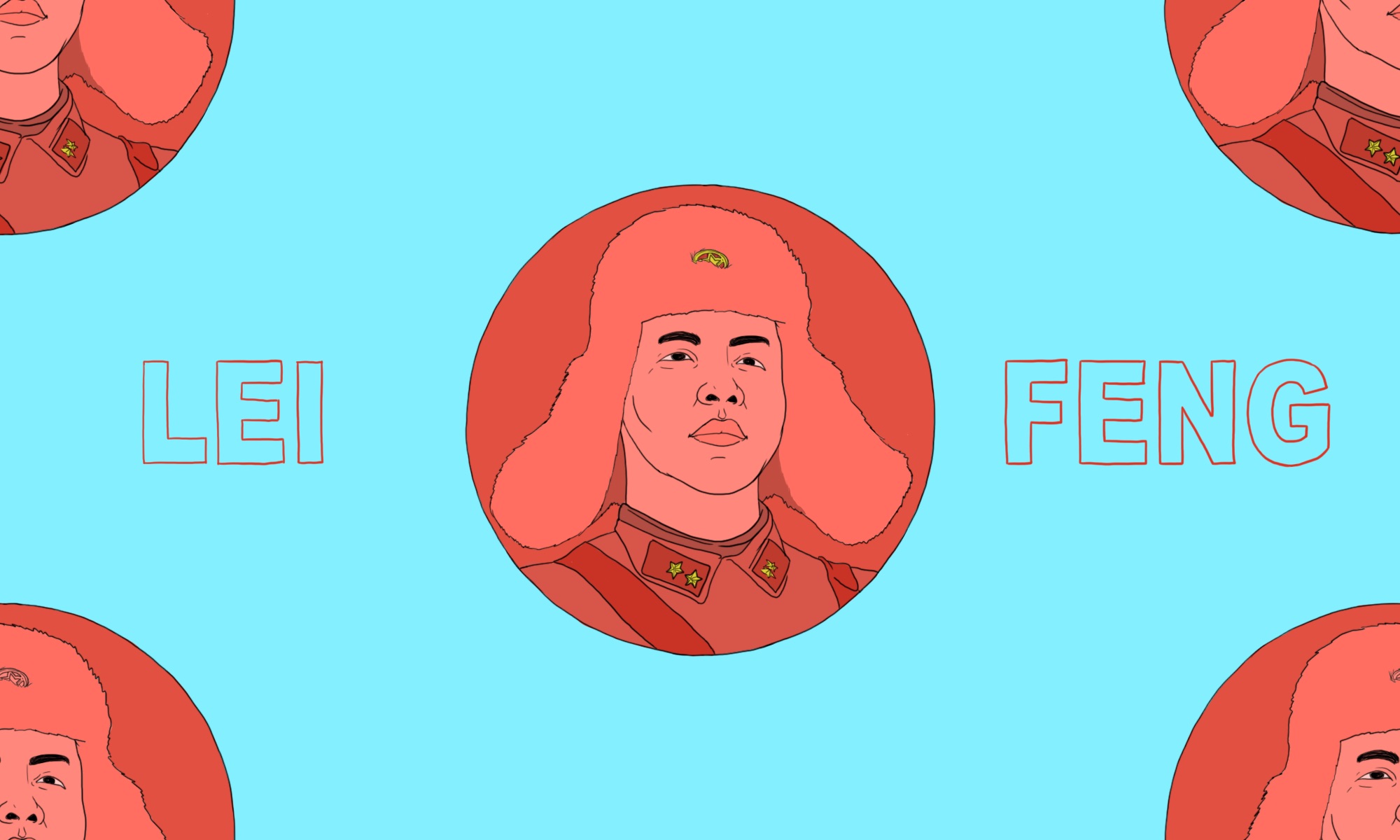

Illustration by Derek Zheng

China is well-informed on household names of the West. Eight-year-olds are taught about Newton, Einstein, and Edison, while entrepreneurs aspire to be Bill Gates, Warren Buffet, or Steve Jobs. Harry Potter is read widely, Picasso hangs in prominent galleries, Shakespeare fills theaters, concert halls ring with Western classical music. It seems strange, then, given China’s importance and history, that beyond Confucius and Mao, there is very little reciprocal understanding of the country’s most notable figures and great minds. The path to a nation’s soul is not through its GDP or current leader, but in the characters it chooses to celebrate or condemn.

This new weekly series, Chinese Lives, seeks to plug this knowledge gap, introducing you each week to a Chinese personality that should be better known outside China. Each in their own way adds color to a country we should all try to better understand.

We begin with a small man who cast a long shadow, the controversial Léi Fēng 雷锋 (1940 – 1962). A five-foot private in the People’s Liberation Army, Lei Feng was Chairman Mao’s archetypal “Good Soldier” who became a Party poster boy. Refusing to be consigned to the Mao scrapheap, he has been reinterpreted for a changing China — and even deployed against COVID-19. Each March 5 sees him celebrated anew as part of “Learn from Lei Feng Day,” where acts of community service are encouraged in the spirit of his selflessness.

Who is Lei Feng?

It is hard to separate fact from fiction. Born in 1940, Lei Feng was orphaned during the Sino-Japanese War. The abandoned child was adopted by the PLA, given food, shelter, and an education in socialism. His choice of jobs — a messenger for the local government, a steel factory worker during the Great Leap Forward, finally a truck driver for the PLA — suggest a full assimilation of Chinese Communist Party morals, and perhaps explains why he was chosen to be the face of dedication, humility, and sacrifice (among other virtues).

Lei Feng’s community upbringing may have spawned his altruism (at least in lore), the evidence for which comes from his diary. In its pages he tallied up each day’s good deeds for a world populated by uncles and aunts in need of help: “The Party is my family, the people are my family,” the diary reads.

No one knows how much of this diary is doctored propaganda, bogus like the choreographed pictures of him doing his “anonymous” good works. It is “almost certainly at least a partial forgery,” as Chinese scholar Orville Schell puts it. His entries imply he took pleasure in being part of a greater whole, an “unrusty screw” whose anonymous acts were small contributions to the socialist cause. His idea of a perfect Sunday seems to be washing five mattresses or 800 pounds of cabbage for his comrades, walking an old lady home in the rain, and then quietly darning someone’s bedcover. The diary also includes public condemnation of a local Party grandee as a “rich peasant,” teaching Chairman Mao’s message to fellow soldiers, and regular dreams of meeting the Great Helmsman.

Most academics agree that Lei Feng is both real and fake, kernels of truth encrusted with spin. In 1961 he featured in the People’s Daily as a success story — “A Suffering Child becomes an Outstanding People’s Soldier” — and was later photographed by the military, specifically in the service of propaganda.

After he was killed by a collapsing telephone pole in 1962 — a decidedly non-heroic death, though perhaps fitting for this hero of small deeds — someone within the Party decided his legacy would forever be that of CCP mascot. In March 1963, Mao entreated the populace to “Learn from Comrade Lei Feng.” Copies of his diary were pressed to the chests of millions across the country. He was re-molded into something more human in the 1980s for a nation rapidly swinging toward the West — new editions of the diaries have him angrily denying trysts with a mysterious “female comrade.”

Why does everyone know him?

Young or old, no one in China is unaware of Lei Feng. He got a big publicity boost from a government campaign for his 50th anniversary in 2012. News outlets were flooded with Lei Feng stories and a new edition of the diary was published with “previously unknown content.” He was, seemingly overnight now also the author of 30 poems, three abandoned novels, and 10 essays.

The time was right for a comeback: citizens and bureaucrats alike were concerned that China was becoming selfish, dissolute, and depraved. His class politics was largely downplayed in favor of his patriotism, community spirit, and Party loyalty, with Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 declaring in 2018 he was “a role model of the times.” Most Chinese have taken part in “Learn from Lei Feng Day” activities while at school, an obligation often dropped when no longer compulsory.

For many he’s a ludicrous symbol, just another piece of top-down Chinese Communist Party propaganda. Criticism has been vocal and well documented.

But some young people hold another viewpoint — that what he stood for is greater than his political ties, rendering any debate over factual accuracy irrelevant. A 2013 survey of 415 Chinese university students, conducted by Professor Elaine Jeffreys of the University of Technology Sydney, found just 3% thought he was “just propaganda,” with 73% viewing him as a role model. Seventy-seven percent believed Lei Feng symbolized “helping others” rather than patriotism or Party loyalty. No one — 0% — thought he was “not relevant to today’s China.”

Lei Feng in culture and society

His face is everywhere. Mugs, t-shirts, and even condom wrappers (for a little while, at least) sport the famous image of the man, looking a little goofy with elephantine ear flaps trailing from his untied fur hat (headgear borrowed specially for the photo). The photographer angled the shot carefully, making him appear a mighty ubermensch instead of the pint-sized reality.

He looms large in state rhetoric over COVID-19. “The more critical the time, the brighter the spirit of Lei Feng,” declared one Xinhua article on March 5. In early February, the National Women’s Federation and the Chinese Communist Youth League urged members “in the spirit of Lei Feng” to check temperatures, aid the sick, and serve those most in need. State media praised Wuhan medics with an everyday Chinese expression: They were “living Lei Fengs” (活雷锋 huó Léi Fēng), a phrase synonymous with selflessness and duty).

The West has no role model like Lei Feng. We celebrate exceptional selflessness, those who suffered for a grand cause or saved millions: Mandela, Martin Luther King, Jr., Jesus. We don’t place people on pedestals for cleaning mattresses.

For some in China, Lei Feng can be a figurehead for community spirit — those mundane domestic acts that mean little to history, but a great deal to those on the receiving end. Humble, but no less important. I now tell the volunteer temperature-checkers in my housing compound they are “living Lei Fengs.” The look of happy gratitude on their faces, the eagerness with which they run to tell colleagues, shows Lei Feng is a little label for a big idea.

Chinese Lives is a weekly series.