China’s new Russia-style disinformation tactics

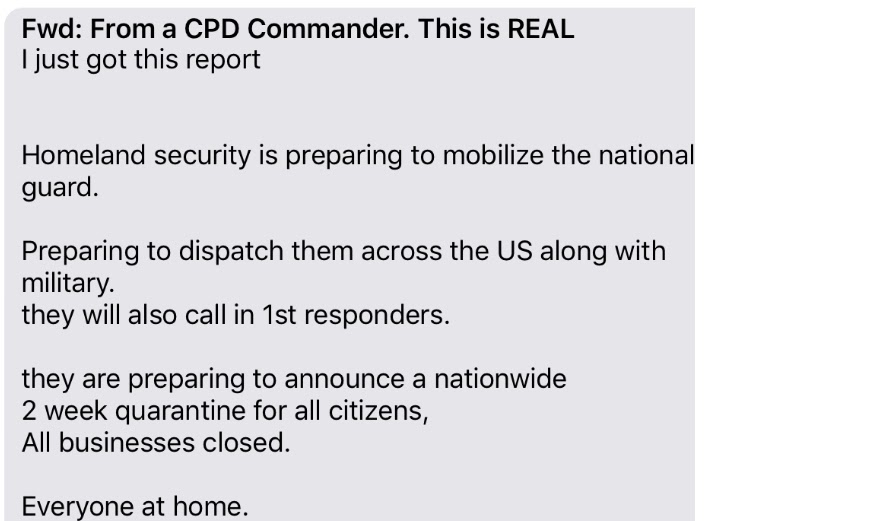

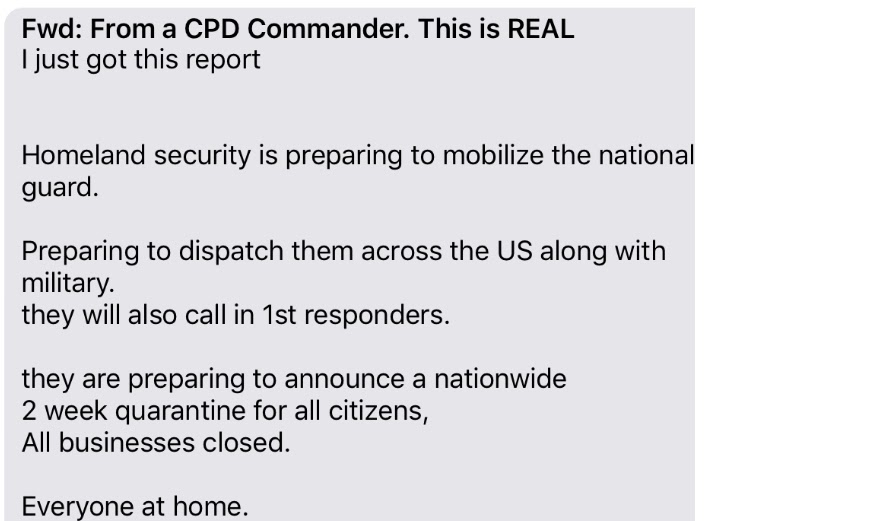

A screenshot of a fake news story delivered via text in March, which the New York Times reports that Chinese agents amplified. Image via Patch.

For three consecutive weeks in March, Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Zhào Lìjiān 赵立坚 pushed the conspiracy theory that COVID-19 had not originated in China. His first indirect promotion of this line was at a foreign ministry briefing on March 4. Then, on March 12, he went full steam ahead, saying that it “might be [the] U.S. army who brought the epidemic to Wuhan,” and asking his followers to “read and retweet” a conspiracy article. On March 22, he reiterated that the “U.S. should find out when patient zero appeared.”

Zhao’s message was then essentially overruled by the Chinese ambassador to the U.S., Cuī Tiānkǎi 崔天凯, who called these theories “crazy” in an interview published only a few hours after Zhao’s last conspiratorial tweet.

However, some American intelligence officials suspected that China was not actually backing away from coronavirus-related disinformation, but rather was likely to “further embrace the more subtle Russian-style approach.” They told this to Julian Barnes, Matthew Rosenberg, and Edward Wong at the New York Times in a story published on March 28.

Those same reporters now reveal that around March 13 to March 15 — right in the middle of Zhao’s conspiracy-mongering — China tested new tactics to spread disinformation. Citing six anonymous officials from six different agencies in the U.S. government, they report:

- Chinese agents amplified existing fake news using text messages, which are much harder to trace than social media posts, though Chinese agents also promoted the fake news through fake social media accounts.

- The fake news consisted of alarming messages that President Trump was about to lock down the entire country as the coronavirus spread.

- The fake news spread so fast that the White House’s National Security Council publicly labeled it as “FAKE” on March 15.

This campaign appeared similar to Russian disinformation because its primary purpose was simply “sowing chaos and undermining confidence among Americans in the U.S. government.” In the past, such as with China’s social media disinformation on the NBA, the goal had been instead to censor criticism of China or protect Chinese core interests about territorial issues, like Hong Kong, Taiwan, or Tibet.

One other implication of the news: The timing of this disinformation campaign makes it less likely that Zhao was truly “going rogue” in the Foreign Ministry, or implementing his own agenda as some had suspected, and more likely that he was acting as part of a plan formulated higher up in Beijing.

A caveat: The New York Times does not have any indication of the scale of the Chinese operation, and, as the report admits, “the United States and China are engaged in a titanic information war over the pandemic.” If the information from American officials is reliable, then the implications are significant, but further reporting could indicate otherwise.

For more on China’s disinformation abroad, see a new report published by the Alliance for Securing Democracy: Friends and enemies: A framework for understanding Chinese political interference in democratic countries.

—Lucas Niewenhuis