All about the Chinese God of Money

Chinese Lives is a weekly series that looks at notable figures from all eras of Chinese history.

Every Spring Festival, Chinese greet each other with a smile and utterance of “May you become rich!” (恭喜发财 gōngxǐ fācái). Westerners often mistake this as the Chinese equivalent of “Happy New Year.” In fact, it is a prayer, offered in the hope that the next year will be a prosperous one.

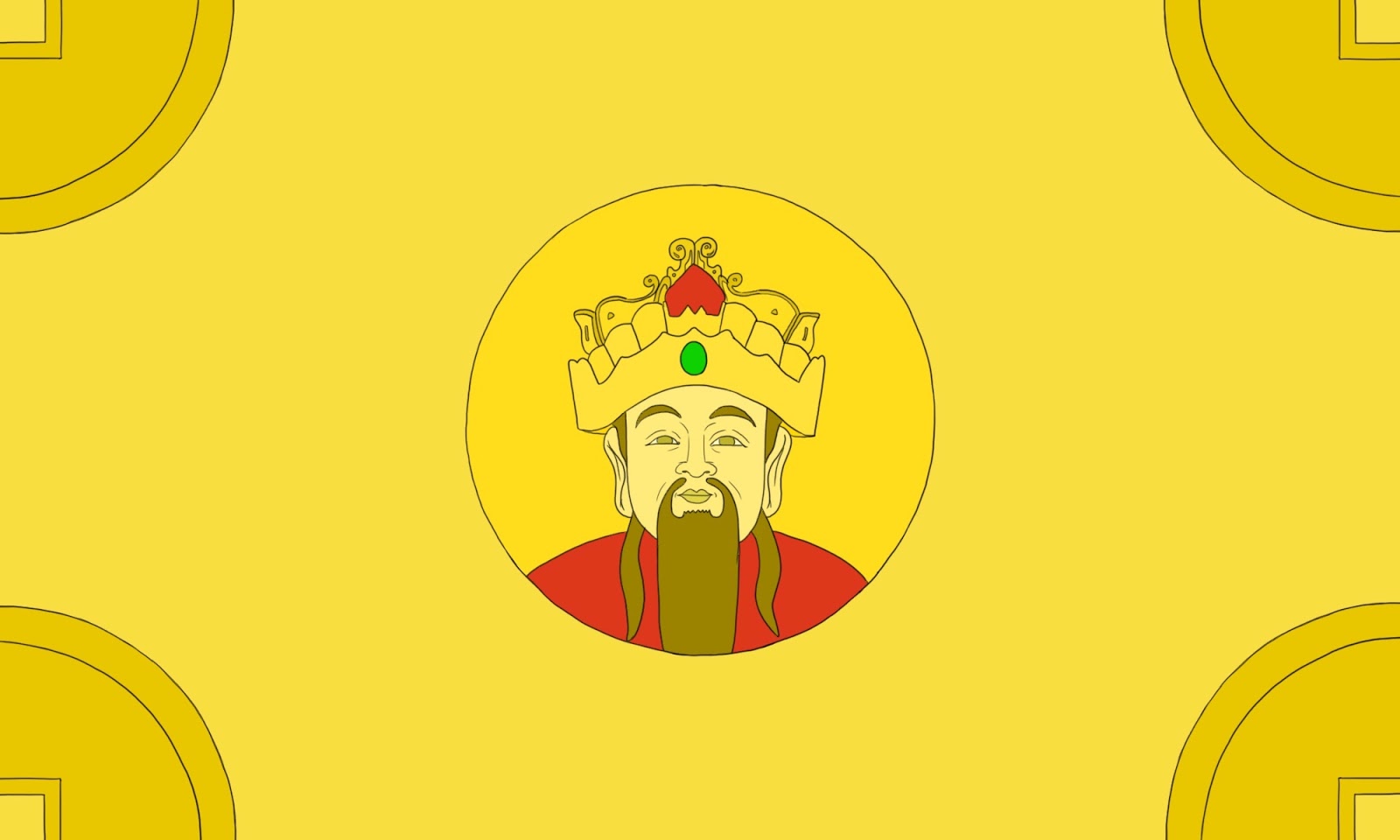

The god that they are appealing to is Cáishén 财神.

Who is Caishen?

Caishen is a temperamental and multifaceted entity, the god of wealth. Much in the same way that the God in Christian tradition is made up of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, so Caishen is divided up into nine different deities, semi-mythical figures from Chinese history who have over time been apotheosized as one of his physical incarnations.

A key part of Daoism and Chinese folk religion, Caishen is the object of prayers across the country, followers hoping some of his vast bounty of wealth, carried about for him by his attendants, will be donated to them.

Traditionally, someone wanting Caishen’s help picks an incarnation responsible for one of the compass points. Making a deal with an American company? Your best bet is Cáo Bǎo 曹宝, Caishen of the West. Starting a local business, or about to finish building your house? Then address your needs to Zhào Gōngmíng 赵公明, Caishen of the Center.

His incarnations are laced with legend — Zhao Gongming was a hermit magician who loyally aided the dwindling embers of the collapsing Shang Dynasty, only to be killed when a supporter of the rival Zhou Dynasty shot a straw effigy of him with an arrow. The man was forced to apologize to the corpse of Zhao and proclaim him President of the Ministry of Wealth. Then there’s Bǐ Gàn 比干, an official during the Shang named by Confucius as one of the dynasty’s three virtuous men. He was executed for advising his ruler to reform his corrupt ways — by having his heart extracted, the ruler curious to see if the old adage that “a Sage’s heart has seven openings” was really true. Together, these nine incarnations cover all things you can profit from: luck, money, gambling, gold, etc.

Caishen didn’t fare well under Maoism. Countless temples and statues were destroyed, his influence all but dying out in a country where Mao and Communism made its own luck.

But with reform and opening up in 1979 and beyond, mainland Chinese came into contact with the “Four Asian Tigers” — overseas Chinese communities from Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, and South Korea. There, Caishen had been kept alive, and they found themselves wealthy and developed. Mainland China had abandoned Caishen and was in poverty. People put two and two together.

The renaissance was swift. Mainland statues of Caishen began including symbols from abroad — a hat from southeast Asia perhaps, or scrolls and ribbons with “gongxi facai” written on them, as from Hong Kong.

Statues to one of the gods of Caishen are all over mainland China today, occupying places of prominence, facing the entrance to greet people going in and out of buildings. From the formal shrines atop Tai Shan (China’s most sacred mountain) to the small models nestled on high shelves in restaurants, perched on hotel reception counters, or sitting in the waiting room of a major conglomerate on the 15th floor, always surrounded by fruit (ripe bananas are luckier) and the ashes of old joss sticks littered at his feet, Caishen is everywhere. In some areas, incense is offered every day before opening time.

But it’s during Chinese New Year that he and all of his incarnations really shine. In the countryside, in the lower-tier cities, in the throbbing metropolises, people pray to Caishen for the same reason: for another step up the ladder. The boat-shaped ingots of gold (元宝 yuánbǎo) he carries appear on everything from New Year posters to Oreo cookies.

China is now populated by businesses of all sizes. It’s a turbulent line, requiring the luck of a gambler. For many, it’s a comfort to know that there’s someone out there who can deal you a favorable hand.

Chinese Lives is a weekly series. Previously: