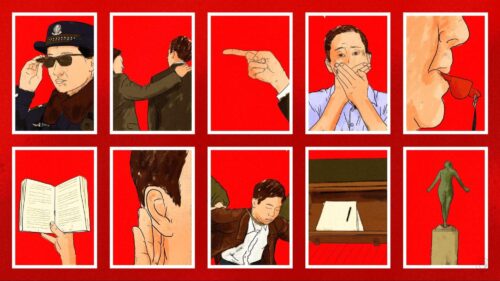

Freedom of expression is dead in Hong Kong

The government of Hong Kong has essentially banned a protest slogan because it carries “secessionist intent,” which is a crime under the new national security law forced on the city by Beijing.

We declared the death of press freedom in Hong Kong on October 6, 2018, when the city declined to renew the visa of Financial Times editor Victor Mallet on political grounds. Today, it’s not just the media in the crosshairs: Freedom of expression for all citizens is over:

“The government says the protest slogan ‘Liberate Hong Kong, Revolution of Our Times’ [光復香港,時代革命 guāngfù xiānggǎng, shídài gémìng] is in violation of the new national security law because it carries secessionist or subversive intent,” reports RTHK. The statement came after yesterday’s protest, where demonstrators, some of whom were arrested, carried signs and chanted the slogan.

The chill has already set in. Many journalists and social media users have deleted posts and articles that they fear could get them into trouble, and some restaurants “that sympathized with Hong Kong’s protests last year have removed posters and Post-it notes critical of the administration,” reports the South China Morning Post. One restaurant says it was warned “that the materials would go against the new national security law.”

The new law has been condemned by activists and governments around the world. British prime minister Boris Johnson said that “up to three million Hong Kong residents are to be offered the chance to settle in the UK and ultimately apply for citizenship.” A former employee of the British Consulate in Hong Kong who was detained last year in China, where he claimed to have been tortured, has already been given asylum in Britain.

Taiwan, Australia, and the United States have also mooted “special measures that would absorb Hong Kongers as refugees.” The U.S. House of Representatives also unanimously passed a bill “imposing sanctions on banks that do business with Chinese officials involved in cracking down on pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong.”

For legal analysis of the national security law, see China law scholars Jerome A. Cohen and Donald Clarke. See also in the New York Times: Hong Kong opens door to China’s hulking security state (porous paywall).