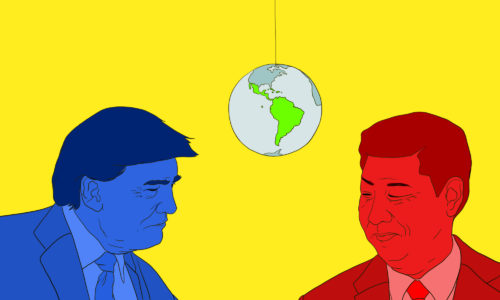

China’s growing clout in the Caribbean

The U.S. is attempting to reaffirm its support for Caribbean countries amid mounting concerns that China wants to become a key political and commercial partner in the region.

Back in January — which feels like a lifetime ago, before the COVID-19 pandemic reached the Western Hemisphere — U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo visited Jamaica, where he warned Caribbean countries not to get too cozy with China. “It’s tempting to accept easy money from places like China,” he declared at a joint event with Jamaican Prime Minister Andrew Holness. “But what good is it if it feeds corruption and undermines your rule of law? What good are those investments if in fact they ruin your environment and don’t create jobs for your people?”

Pompeo also attended the inauguration of Dominican Republic President-elect Luis Abinader on August 16, despite the spike in COVID-19 cases there, to affirm American support for the country. The visit came amid mounting concerns that China is trying to displace the U.S. as a key political and commercial partner in the region.

Prone to natural disasters, where a single hurricane or flood can set back an island’s economy for decades, Caribbean countries desperately need access to funding to build resilient infrastructure. Some Caribbean countries are ineligible to access loans from international institutions like the World Bank and the IMF. In the midst of a global pandemic which has severely hampered tourism—the Caribbean Development Bank estimates that many of the Caribbean countries will fall into recession this year with declines in real GDP ranging from 1.5 percent to 10 percent across countries—Caribbean nations need alternative sources of funding. As such, countries in the region are increasingly turning toward China for concessional loans to finance big ticket infrastructure projects.

China’s growing clout on the U.S.’s “third border” does not bode well for U.S. interests in the region. For this reason, the United States should continue to support its Caribbean partners in economic growth, disaster resilience, and people to people exchanges; otherwise, it runs the risk of its Caribbean partners falling prey to the worst aspects of China’s predatory practices.

China’s COVID diplomacy

When COVID-19 struck the Caribbean, China initiated an aggressive messaging campaign to promote the notion that its assistance was crucial to the wellbeing of each Caribbean country. Journalists have written extensively about this “mask diplomacy,” and the Wilson Center has even been tracking how much COVID-19 aid China has given to Latin America and the Caribbean. A statement from China’s Embassy in Grenada claimed, “Grenada has brought COVID-19 under control to a large extent because of the assistance from China in a variety of forms, with PCR testing machines, rapid tests and masks.”

Several Caribbean prime ministers have lauded China for its COVID-19 foreign assistance, drawing comparisons to the apparent lack of engagement on the part of the United States. “Politically motivated campaigns and stigmatization, with a xenophobic and discriminatory bias, have not been able to discredit the achievements made by China in controlling and recovering from the devastating effects of this disease,” Cuba’s Deputy Foreign Minister Rogelio Sierra said in July at a video conference of foreign ministers from Latin American and Caribbean countries. “Stronger ties with China, which is best reflected by the China-CELAC [Community of Latin American and Caribbean States] Forum, will contribute to the sustainable development of our peoples.”

At that same July forum, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi announced a $1 billion loan so that Latin American and Caribbean countries could buy a still unreleased COVID vaccine from China.

In early June, Antigua & Barbuda Prime Minister Gaston Browne announced a plan to convene an ALBA-China forum to strengthen strategic and economic alliances between the regional bloc of Caribbean countries and China.

Of course, China’s COVID diplomacy represents just one aspect of an ongoing foreign policy strategy to augment its presence in the Caribbean, following China’s decade-old practice of generous loans and investments to financially ailing countries in the region.

The Belt and Road reaches the Caribbean

Over the past 10 years, the Chinese government and private corporations have loaned billions of dollars in the Caribbean. Jamaica, Trinidad & Tobago, the Bahamas, Barbados, Antigua & Barbuda, Dominica, and Grenada have all signed on to join the PRC’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), enticed by gifts, loans, and other investment packages. China has loaned Jamaica $720 million to build the North-South Highway, provided loans of over $2.5 billion to Trinidad and Tobago, and loaned billions of dollars in the Bahamas — just to name a few examples.

After Guyana signed on to the BRI, President David Granger maintained that his nation would continue to seek out Chinese funding. “We cannot develop without infrastructure and we just do not have the capital to do it on our own. So, whether it comes from America, China or Britain we have to have it, and of course we have to look for the best deal,” Granger said.

In Barbados, China state-owned enterprise (SOE) COMPLANT is carrying out a construction project to convert Sam Lord’s Castle into a Wyndham resort. In Antigua, the China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation erected an airport terminal. In Grenada, another Chinese SOE has helped finance the construction of several local housing projects. China has also fit the bill for sports stadiums across the region — a strategy that some foreign policy analysts refer to as “stadium diplomacy” — including a new $40 million athletic stadium in Grenada.

In addition, China is making inroads in the field of education. China has set up Confucius Institutes in both Barbados and Antigua & Barbuda. Local press reports indicate that over 570 students from Barbados, Grenada, Dominica, and Antigua & Barbuda were awarded scholarships to study in China in 2019.

All that glitters is not gold

A chief concern is that Caribbean countries will fall into “debt traps” with China, akin to other countries in Latin America and Africa. There are significant questions around the transparency of these investment deals.

Indeed, the Caribbean Investigative Journalism Network revealed that, in many instances, negotiations and terms of the agreements on China-Caribbean government-backed projects are seldom publicized. This has raised concerns around suspicious procurement processes, labor processes, and adherence to building codes.

In Suriname, there are fears that decades of accumulated debt might impede future development and expose the country of 500,000 people to future liabilities. In 2012, Jamaica signed a $630 million contract for a highway project with China Harbour Engineering Corporation (CHEC) that waived the Jamaican government’s rights to immunity, essentially ceding sovereignty to China and rendering all publicly-owned assets in Jamaica accessible by seizure.

There also exists a stark disconnect between the praise lavished on China by Caribbean government leaders and the deep skepticism of China’s intentions from the local population.

After China constructed a China-Dominica Friendship Hospital in Roseau, Dominica’s capital city, Dominica Prime Minister Roosevelt Skeritt remarked, “China is a true friend of Dominica and always stands together with Dominica during hard times.”

However, there are signs that China’s overtures to the Caribbean have not been well received by locals. Social media netizens have often responded negatively to Chinese claims of largesse. After China donated PPE to Barbados, a number of social media postings questioned China’s motives, with comments like, “Chinese want to take over Barbados slowly, there’s always a catch to everything”; “Send it right back!!!!”; and “They will own Barbados soon.”

China has sought to use credible third-party voices to come to its defense, including Chinese diaspora in the region and Caribbean students, businesspeople, and academics who have worked or studied in China. In a recent meeting of the Association for Barbados China Friendship, Chinese Ambassador to Barbados Yan Xiusheng urged members to “tell good stories about China,” highlighting China’s humanitarian aid and defending its Hong Kong national security law. But despite a growing number of Caribbean citizens choosing to work or study in China, the number remains far too small to make any significant impact on public opinion.

Cross-strait quarrels in the Caribbean

The Caribbean also represents an interesting battleground between mainland China and Taiwan. Of the 15 countries that still maintain diplomatic relations with Taiwan, five of them are in the region: Belize, Haiti, St. Lucia, St. Vincent & the Grenadines, and St. Kitts & Nevis. Taiwan has been spending millions in humanitarian assistance to bolster its image in the region.

One such diplomatic battleground is Haiti, an island nation of 11 million that has been repeatedly devastated by natural disasters and remains one of the poorest countries in the Western Hemisphere.

In April, Haitian President Jovenel Moïse visited Taiwan’s embassy to discuss strengthening diplomatic ties — Taiwan responded in kind by donating 1,000 tons of rice for food and nearly 300,000 face masks, among other humanitarian-related assistance. Taiwan has also offered training to Haitian healthcare workers, established nationwide sanitation campaigns, financed the purchase of new ambulances, and exchanged medical advice via videoconference from Taiwan’s best hospitals.

Yet, China has also made a number of public overtures to Haiti, as the country continues to reel from social unrest and rampant poverty. In its efforts to diplomatically isolate Taiwan, China has appealed to Haiti through a variety of economic relief packages — free assistance, interest-free loans, concessional loans — if Haiti pledges to abide by the One China principle.

For now, though, Haiti has continued to align itself with Taiwan and the United States. The Haitian government joined a litany of other Western countries in condemning China’s recent implementation of its national security law in Hong Kong. In a published statement, the Moïse administration said it “deplores the fact that this law will inevitably lead to a significant, even irreversible, decline in the fundamental freedoms that have ensured the prosperity of Hong Kong and its people for several decades.”

In early July, Taiwan helped the Belizean government establish a novel warning system to aid the Central American nation’s response to natural disasters. Taiwan’s Ambassador to Belize, Remus Chen (陳立國 Chén Lìguó), also delivered a $2 million COVID-19 relief package with 90,000 Taiwanese-produced surgical masks and 150 forehead thermometers.

Taiwan also spends millions each year in the “Three Saints” in the fields of education, health, agriculture, and infrastructure projects. In November 2019, a U.S., World Bank, and Taiwan trade delegation visited St. Lucia to explore investment opportunities. The Taiwan embassies in the Three Saints provide millions for scholarships, teacher training, high school agricultural vocational training, and even school supplies and laptops.

In health, the Taiwanese provided training for local medical professionals at Changhua Christian Hospital, donated medical equipment to hospitals, and launched a $2 million diabetes capacity building project in St. Vincent & the Grenadines. In agriculture, Taiwan built an Agro-Tourism Farm Co-Op in St. Kitts & Nevis and sent technical missions to share banana growing techniques with St. Lucian farmers. Volunteers from Taiwan’s International Cooperation and Development Fund (ICDF) offer technical assistance to the Three Saints in areas such as the environment, public health, agriculture, education, and information technology. With regards to infrastructure, Taiwan gave a $20 million loan to build the St. Vincent modern parliament building, and made several donations to fix roads and provide island-wide internet service in St. Lucia. All of this foreign assistance is an effort to keep the remaining Caribbean allies out of mainland China’s reach.

U.S. engagement in the Caribbean

The United States offers a clear alternative to China’s predatory practices in the Caribbean. Our engagement includes strengthening democratic institutions, preventing corruption, protecting the environment, encouraging freedom of the press, and promoting a vibrant civil society. The U.S.-Caribbean 2020 strategy focuses on six pillars of engagement: health, education, energy, prosperity, diplomacy, and security. The U.S.-led Caribbean Basin Security Initiative, a $600 million program now in its 10th year, has produced success in seizing drug shipments and keeping children away from crime. The new Growth of the Americas Initiative facilitates private sector development throughout the whole Western Hemisphere. And as the hurricane season continues, the United States provides disaster assistance via the U.S.-Caribbean Resilience Partnership.

Since the beginning of COVID-19, the U.S. has provided $20.5 million to the region through the U.S. Agency for International Development to scale up Caribbean risk communication efforts, provide water and sanitation, prevent and control infectious diseases in health facilities, manage COVID-19 cases, build laboratory capacity, and conduct virus surveillance. This doesn’t include the millions in additional donations by the CDC, SOUTHCOM, and U.S.-based NGOs. In July, Secretary Pompeo and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin both supported Caribbean countries to access $1.7 billion in funding from the IMF for COVID-19 related assistance. The U.S. also continues to cooperate with Taiwan and other likeminded partners on COVID-19 assistance to the region.

The United States encourages Caribbean youth to participate in our exchange programs such as Fulbright, the Young Leaders of the Americas Initiative, Youth Ambassadors, and our new Academy of Women Entrepreneurs. We keep engaging local audiences through social media, including WhatsApp, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter.

But most of all, the U.S. leverages its most valuable comparative advantage, which lies in its deep historical and cultural ties to the region. So many Caribbean people have family members living in the United States. Some of our most important American icons had roots in the Caribbean, like Malcolm X, whose mother was Grenadian; Shirley Chisholm, who grew up in Barbados and became the first Black female presidential candidate; and Democratic vice-presidential candidate Kamala Harris, whose father was born in Jamaica. We should tell more stories about the countless Caribbean-Americans who have shaped our country’s history and will continue to shape our country’s future. In the end, it is our diversity that has always given us strength, and it is our diversity that will win hearts and minds in the Caribbean.

The views expressed in the article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. government.