In China, the Trump administration sees a rising power that threatens American primacy. It has reacted the same way white nationalists are reacting to the Black Lives Matter movement: with belligerence and racist rhetoric.

The Trump administration is now more than a month into its near-daily spate of anti-China actions and pronouncements. Just this summer, the administration has moved to label Chinese media outlets operating in the U.S. “foreign missions.” It has terminated Hong Kong’s special status in response to the enactment of Beijing’s new national security law for Hong Kong. It closed the Chinese Consulate in Houston with just 72 hours of notice and without making clear its reasons for doing so. Attorney General William Barr has trumpeted the Department of Justice’s stepped-up “China Initiative,” focused on alleged intellectual property theft and espionage by China, now opening a new case every 10 hours. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo all but declared a new Cold War with China in his speech at the Nixon Library on July 23, stopping just short of calling for regime change. Shortly afterward, Donald Trump decided to force ByteDance, China’s most valuable start-up, to sell all of its U.S.-based operations for its hit video app TikTok, and later also signed an executive order attacking the popular super-app WeChat. All summer, as COVID-19 cases surged in an uncontrolled spread in more than half of U.S. states, he has repeatedly used the phrase “China Virus” and the even more blatantly racist “kung-flu” to refer to the deadly disease.

Pundits and analysts have floated many hypotheses as to why the administration’s moves against China have been so frenzied. Distraction is a well-worn page in the Trumpian playbook, and a full-court press against China — the country Trump and many Americans insist is to blame for the virus — is an ideal distraction from his criminally inept handling of the pandemic. Perhaps it’s a case of wag the dog: Trump hopes to create some kind of an incident — even a kinetic one, if it can be contained — that will produce the “rally ’round the flag” effect and bolster support at the polls. It could be an effort to create “facts on the ground” — to scorch the earth, so as to make any reversal, rollback, or even “reset” more difficult for an incoming Biden-Harris administration should Trump lose the election in November, as polls strongly suggest he will. Or — and this may be giving the Trump administration too much credit — it’s possible that the plan is to bait the Biden transition team into “pulling a Flynn”: offering improper backchannel assurances to Beijing in the way Trump’s short-tenured National Security Advisor Michael Flynn did in calls with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak on sanctions. It could be, and likely is, some combination of these things.

But there’s more to it than this. Throughout the summer, even as the Trump White House was ramping up its anti-China push, it also faced a massive domestic upheaval: the nationwide protests that broke out after the killing of George Floyd. Watching Trump’s response to Black Lives Matter and to the George Floyd protests — a reaction that epitomized the feelings of many conservative white Americans — we were struck by a profound parallel to the way the U.S. has responded to China during the same period. Both are rooted in the fear of loss of primacy and privilege. It’s a fear that many don’t even know they feel, but it’s one that Trump has an uncanny, instinctive ability to harness and to amplify. Just as Trump’s presidency and the white ethnonationalism it has empowered together represent an irrational response to the loss of white privilege in an increasingly diverse, multicultural United States, so, too, does Trump’s foreign policy — especially toward China — represent an irrational response to a similar loss of American privilege in an increasingly multipolar world.

When the dust cleared from the collapse of Soviet Communism — first in Eastern Europe and then, at the end of 1991, in the U.S.S.R. itself — the U.S. stood unchallenged on the global stage, confident in the historic victory of liberal democratic capitalism. Even without Trump’s willful abdication of global leadership on issues like climate change, his frequent attacks on long-standing allies, and his petulant withdrawal from the World Health Organization in the midst of a global pandemic, American power was sure to wane, since power is always measured relatively. The rise of China and of India, the growth (however unsteady) of a European identity, a revanchist Russia — all of these things ensured that this would be so. Trump’s election was probably more consequence than cause of the global surge of populist nativism that has marked his time in office. But it’s hard to imagine a president who could have both done more to diminish American prestige and felt more anger over its diminution.

The same could be said for Trump and his followers domestically. For all the earnest hope Obama’s election in 2008 ushered in, the dream of a post-racial America was always doomed to dissipate. The Tea Party, with its racially charged vows to “take back” its country, was proof enough of that. The trend, though, was clear: America was fast becoming a “minority white” country, and census projections now show this will happen before the middle of the century. Trump has done more than anyone to surface the ugly, racist anxieties of white America and thereby, ironically, give strength to the forces that want to end its dominion — and his.

Zoom out from the national to the global, and the twilight of white privilege in America looks a lot like the twilight of American hegemony in the world: The armed white nationalists who have grown more vocal and visible in the years since Ferguson find their analogy in the China hawks urging us into a new Cold War. White fragility is American fragility in microcosm.

Trump’s courting of anti-Asian racism has been deliberate: It connects the domestic white nationalist project with his hyping of the China threat.

The historian Adam Tooze drew the connection in a recent Sinica Podcast. Speaking of Donald Trump’s July 4 speech at Mount Rushmore and Pompeo’s remarks later that month, he noted that they represent “an extraordinary knitting together of the domestic culture war front with the external Cold War position.” The liberal New York Times, with its 1619 Project, is razing history as the Chinese Communist Party does.

It is time to recognize that racism is a major component of the Trump administration’s anti-China crusade, and to acknowledge that it is racism that ties the micro to the macro. And while since late May the George Floyd protests have rightly focused national and international attention on persistent structural racism against Black Americans, let us not forget that since March we have seen a dramatic uptick in anti-Asian hate crime in America. For the Trump administration, this surge in anti-Chinese bigotry, with its inevitable spillover into racism toward all East Asians, is a feature — not a bug. His courting of anti-Asian racism has been deliberate: It connects the domestic white nationalist project with his hyping of the China threat.

Today’s scapegoating of Asian Americans has been encouraged from the top levels of government, as the Trump administration continues to paint Chinese people in America as vectors of disease, agents of espionage, and threats to national security. Racist stereotypes about East Asians in general and Chinese in particular — even supposedly benign “model minority” stereotypes about discipline, obedience, and diligence — are extrapolated to a whole country, focusing in particular on China’s growing prowess in technology. The supposed hyper-productivity of the Chinese, as with the Japanese three or four decades ago, makes them a major economic threat. The Chinese become a collective, a de-individuated hive mind, all marching in lockstep and doing the bidding of their masters in Beijing, representing a “whole of society threat” necessitating a “whole of society response.”

The parallels between domestic American racism and American foreign policy have been noted before. Mittie Maude Lena Gordon, founder of the Peace Movement of Ethiopia — the largest Black nationalist organization established by a woman in the U.S. — argued in 1942 that the “destruction of the white man in Asia is the destruction of the white man in the United States.” She noted a direct connection between the ascent of white supremacist ideologies in the United States and its rise in Asia. “The complete freedom of India will bring complete freedom to the American [B]lack people,” Gordon wrote, “because the same men are holding them in slavery.”

While a great many Americans now recognize and decry the racially charged fear at the heart of “Make America Great Again,” they’re less able to recognize it at the international level, and this makes this fear easier to activate even among self-described liberals and progressives. This may explain why this sudden, inchoate assault on all things China, for all its obvious emotionalism and irrationality, has managed to garner support from both sides of the aisle. Perhaps we can take some comfort in the success of BLM: If white Americans, as many have shown themselves able to, can recognize the enduring impact of white supremacy in America, perhaps Americans can come to a similar realization about American supremacy at an international level.

While a great many Americans now recognize and decry the racially charged fear at the heart of “Make America Great Again,” they’re less able to recognize it at the international level.

The Trump administration will insist that its project is about national security, or American jobs, or fair trade. Americans would be right to expect these issues to be taken seriously by any administration and would be right to expect further that their government would take a principled and effective stand against the kinds of gross violations of human rights that Beijing has perpetrated in Xinjiang and elsewhere.

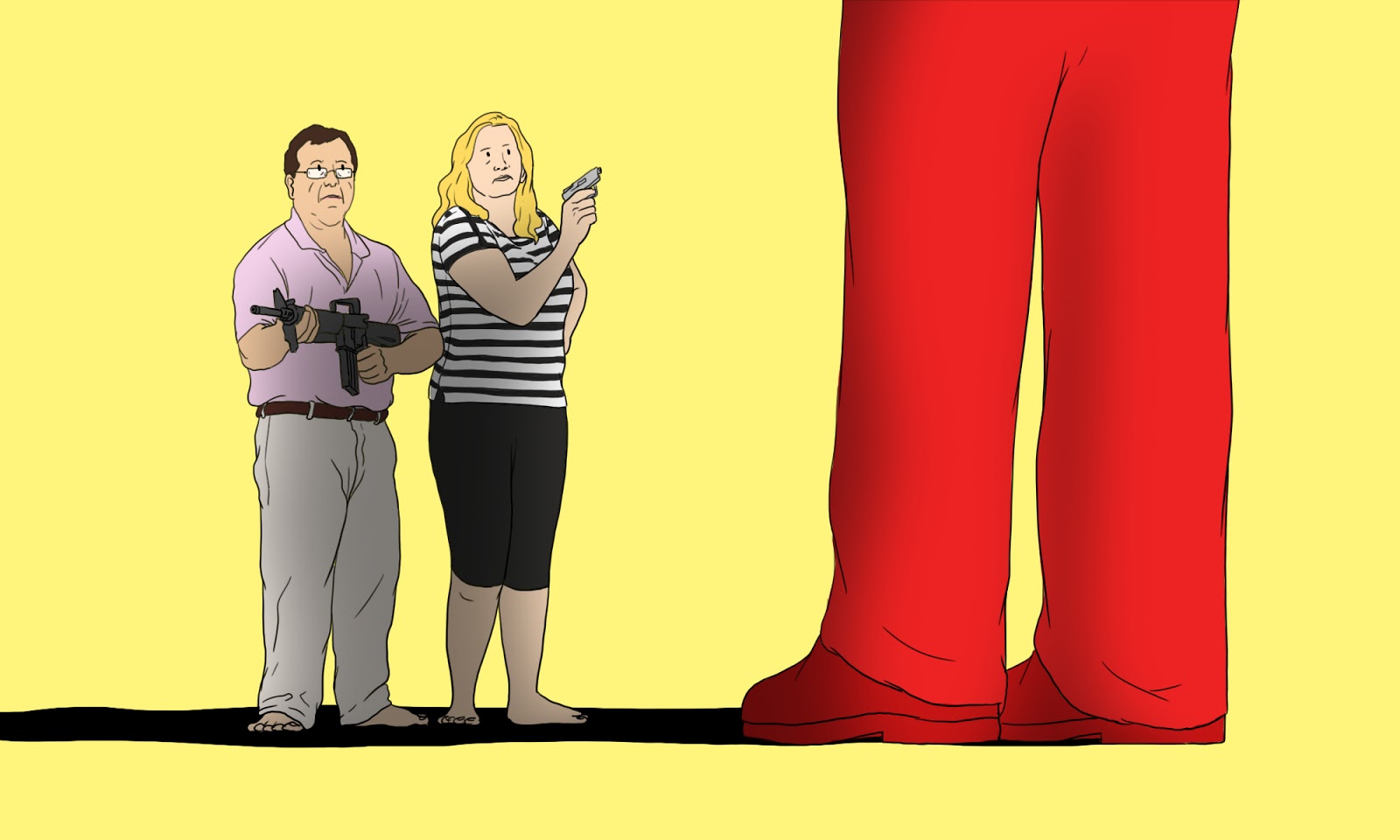

But none of these things are actually animating the current administration’s policies toward China. At bottom, it’s a reaction to this threat to privilege and hegemony, not always acknowledged, but no less easy to spot. Conservative white Americans, conscious that their day in the sun draws to an end, point to law and order, and the preservation of heritage, of sacred history; the U.S., also aware of the approach of twilight, points to national security and to sacred American values. There is an implicit assumption on the part of both that the order they champion is morally superior. Americans tend to see themselves in the world as the hero in the white hat, standing up for democracy, fair play, and human rights; unfortunately, they resemble more closely Mark and Patricia McCloskey, the St. Louis couple who infamously pointed their guns at protesters. Too many Americans see the China of today — prouder, louder, more assertive — as the “uppity thugs” of the McCloskeys’ imaginings.