July 1991, the Great Hall of the People. An opera was being staged on Máo Zédōng’s 毛泽东 life to celebrate the 70th Anniversary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Sporting a freshly-shaved forehead and a chin garnished with the characteristic mole, Mao’s 21-year old grandson had (after “considerable effort” according to the make-up artist) been made to look like the Great Helmsman. This grandson was a living relic, a vessel for the blood of the Chairman and his revolutionary spirit.

This was the only time Máo Xīnyǔ 毛新宇 successfully filled the shoes of his illustrious grandfather.

An old Chinese proverb says that “When a man gets into power, even his chickens and dogs ascend to heaven.” China’s so-called “princelings” — powerful descendants of original senior Party officials showered with wealth and opportunity — are to be found across the political system, even with Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 himself. They’re an object of resentment in China, evidence of hierarchy, privilege and nepotism in a Communist government. But no one embodies the excesses of this system like the Chairman’s overweight, bumbling grandson. Had things gone differently, he may have been China’s very own Kim Jong-un.

Who is Mao Xinyu?

Mao’s only grandson descended on the male line, with nothing to recommend him aside from the family name he carries like a sacred flame. Born in 1970, Xinyu will likely only have foggy memories of his grandfather, who died when he was only five — but not before assigning him the optimistic name “Xinyu,” which means “New Universe.”

Mao hated the idea of senior Party offspring inheriting power. They were a “disaster,” their cushy upbringing risking a nation ruled by spoiled ingrates. The revolution must be continued by leaders worthy of the name, who had struggled like their forefathers.

So it’s ironic there’s evidence that he toyed with the idea of grooming someone in his family to be his successor. Perhaps his nephew Máo Yuǎnxīn 毛远新, or his eldest son Máo Ànyīng 毛岸英. But the former was too young, the latter killed in the Korean War. Xinyu’s father was schizophrenic, so dynastic dreams were abandoned.

Xinyu was a little prince regardless, growing up cocooned by a small army of servants and guards, the only child of absentee parents, who for his first 11 years were based in Russia. He joked with classmates about his plans for when he came to power. “In a generation of ‘little emperors,’” said an article in the Taipei Times, “he appeared to fit the mould better than any, logging mediocre test scores and tipping the scales at more than 114 kg.”

The glorious past is the lens through which he sees the world. Back in 1989, students asked him to lead a group of hunger strikers. “I resolutely refused,” he later explained. “I’d approve if it was in support of Chairman Mao, but I’d never agree to anything that negates socialism and promotes bourgeois liberalism.” June 4 was just another day, spent learning to use a Chinese typewriter.

His life’s work has been to dutifully promote his grandfather — a “god” — and study his brand of Communism, “Mao Zedong Thought.” He’s appeared in documentaries about Mao and until recently had a microblog for the People’s Daily, boasting 11.8 million followers by 2014 and filled with Maoist tidbits.

He’s a strange anachronism in a nation that has de facto rejected everything Mao stood for, a reminder of the speed of change. While working at a hotel in central Beijing in 1994, Xinyu exclaimed, “Granddad was right, theory must be united with practice!” — Maoism deployed in the name of hospitality management.

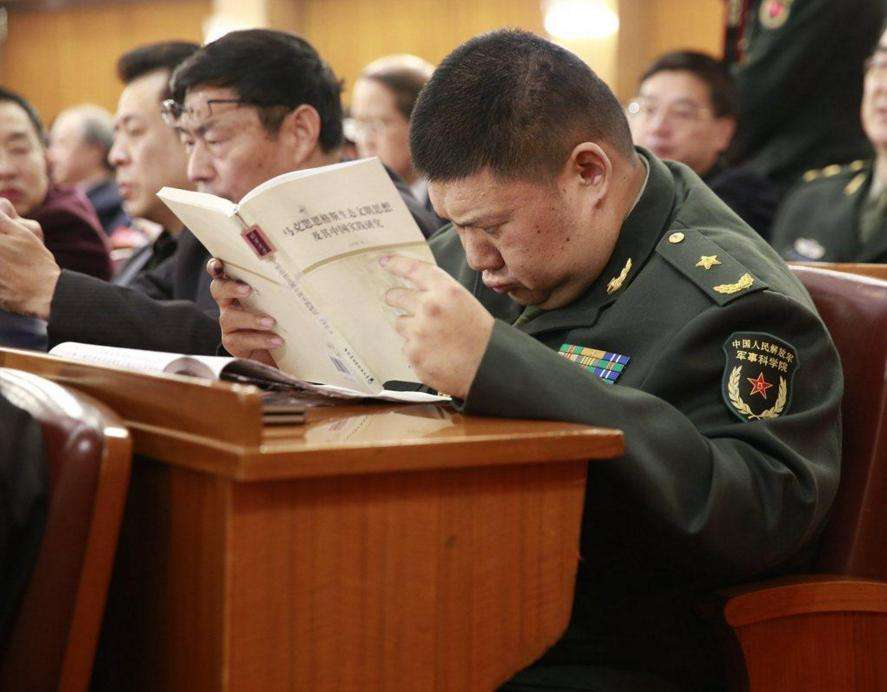

After graduating from the history department of Renmin University in 1992, he started a doctorate on the history of the CCP in the People’s Liberation Army’s elite Academy of Military Sciences in 2003. He became their researcher on Maoist philosophy soon afterwards, giving lectures at Guangzhou University and writing several books on his grandfather (with sticky bits like the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution left out).

Prince and privilege

“So far, we haven’t seen any results from his studies,” Liu Shanying, a professor at the Institute of Political Sciences under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, told the LA Times. “He hasn’t come up with any new ideas about his grandfather’s theories. From an academic view, he lacks achievement.”

Perhaps he earned this highly respected position because his father held the same post several decades before. Xinyu has also cited “family” for his sudden and controversial elevation by the PLA to the lucrative rank of Major General in 2009, pompously explaining, “All the people take their love and respect for Mao Zedong and transfer it onto my person.” At 39, he was the youngest general in the PLA — a spokesperson saying this was only natural given his “many achievements.”

But a general’s uniform, far from helping, seems only to exacerbate Xinyu’s clownish and portly appearance:

Picking his nose after a TV recital of one of his grandfather’s poems hasn’t helped, either. Xinyu is an easy target for those on social media who want to vent their anger at the privilege of the princelings.

But he cannot escape his famous name, with state media keen to portray him as an inheritor of the so-called “red gene” and a part of the “third red generation” (红三代 hóng sāndài) carrying forward the CCP’s revolution into the 21st century.

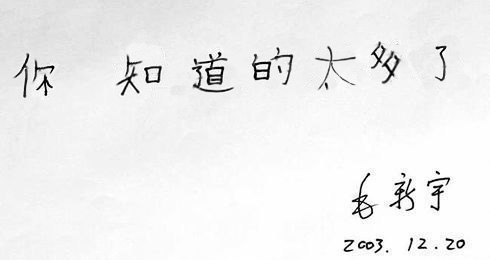

Try as they might, Xinyu is no Zedong. Mao’s distinctive style of calligraphy is familiar to most Chinese, while scorn was poured onto Xinyu when his childish scrawls were held up by state media as a fine inheritance from the Chairman:

State media is quick to defend Xinyu and prove his diligence, essential given he has a seat on the political advisory body Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CCPPC).

He is “a great talent,” writes one Weibo yes-man. His calligraphy only “looks simple,” deliberately “written in the style of a child of six or seven years old, expressing nostalgia and yearning for the beautiful life of childhood.” A man so imbued with everything Mao, including his calligraphy, seems an unlikely candidate for the avant-garde.

He has created the fourth generation — his son Máo Dōngdōng 毛东东 (now 17) and daughter Máo Tiányì 毛甜懿 (12). His first wife was a waitress he married in 1997. He met his second wife, Liú Bīn 刘滨 — an air hostess — in 2000.

A buffoon on the surface, Xinyu may also have a dark side. In 2002, his first wife was reported sent to Qincheng Prison, a maximum-security jail normally housing political prisoners, after she began quarrelling with Xinyu, who wanted to divorce her. It’s not clear who decided she should be sent to Qincheng. She died there in 2003.

The exact nature of his finances is uncertain, but is unlikely to rival the millions amassed by other CCP princelings. He’s portrayed as living frugally like his grandfather, claiming he and his wife only live off a combined salary of 8,000 yuan ($1,170) — without saying if this is per month or per year. This is explained as being the salary rate 20 years ago, but would place him some distance behind the average pay of a Major General today, listed as 23,000 yuan ($3,360) per month in 2018.

Xinyu is a tricky anomaly: Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign has put nepotism on blast. Yet cutting off Mao’s descendants would be inauspicious, almost ungrateful, given his services to China — Mao’s hard-line stance against princelings quietly forgotten for his own posterity.

Chinese Lives is a weekly series.