September 7 marks the anniversary of the Boxer Protocol, signed in 1901, an “unequal treaty” that signaled the end of the Boxer Uprising, itself a major chapter in the development of the “yellow peril” trope. The contested legacy of the Boxers is with us still, and can be seen in how we talk about the COVID-19 pandemic.

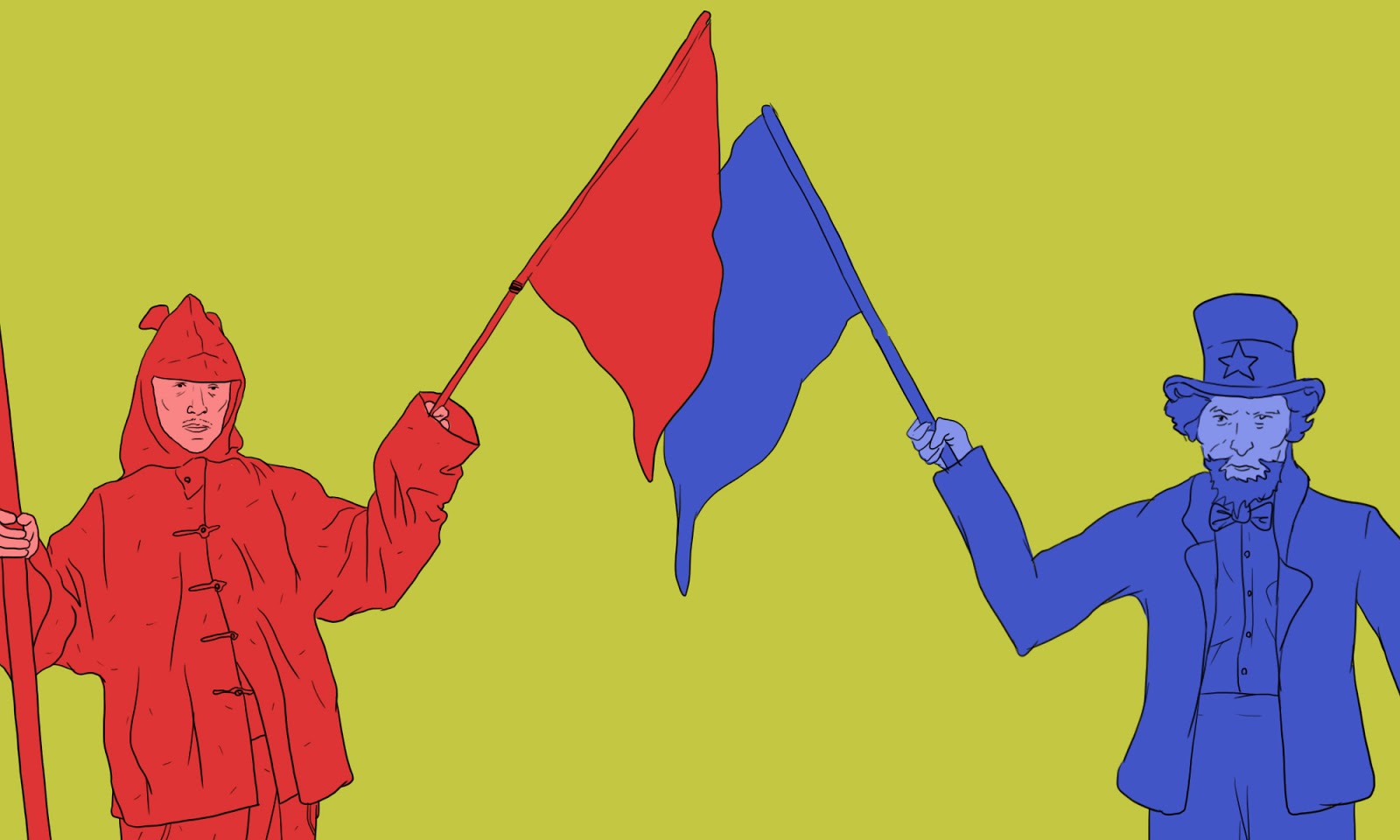

Donald Trump’s excessive use of terms such as “Chinese virus” or “kung flu” — or even, at a rally in Phoenix this past June, “the China” — recalls a history that goes back over 150 years to the origin of the “yellow peril” trope, the racist fear that East Asians pose an existential threat to the Western world, and one that has boiled over with the current pandemic in ugly and even atrocious ways.

In Italy, a Chinese man entered a gas station to make change for a 50 euro note when someone broke a bottle over his head. In Munich, a Chinese woman of German descent was sprayed with disinfectant by her neighbor, who screamed “Corona!” at her and threatened to cut off her head. In New York City, a woman grabbed a female Korean student by the hair as she was entering her building, yelled an expletive at her, and punched her in the face, dislocating her jaw. One survey found 43% of Chinese Canadians have been threatened because of the pandemic, while another found that 60% of Asians in the U.S. have seen an Asian being blamed for it.

Where did such an idea even come from? As intellectual diseases go, Islamophobia is an old one (see: the First Crusade to Jerusalem in 1099), but for many young Americans today, it has a recent catalyst: the September 11 attacks. “Yellow peril” fear and violence against Asians in America similarly have both a long history and a historical catalyst.

Many Americans are too unfamiliar with just how violently Chinese immigrants were attacked and rejected in the U.S. starting more than a century ago, and it’s worth recalling a few key examples from history: In 1854, the California Supreme Court ruled in People v. Hall that Chinese could not testify against whites; Chinese gang violence in Los Angeles resulted in the death of a white man in 1871 and an angry mob that lynched about 20 Chinese men, many of them cooks; the U.S. passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, prohibiting all Chinese immigration (it would not be repealed until 1943); and in Wyoming in 1885, British, Irish, and Swedish miners, fearing that Chinese immigrants were driving down their wages, murdered, mutilated, and burned at least 28 Chinese miners.

But the “yellow peril” was also, like Islamophobia, catalyzed by specific historic events. The most important one? The Boxer Uprising.

How the Boxers changed everything

One of the principal chapters in the development of the “yellow peril” trope, the Boxer Uprising lasted from 1899 to 1901. Before this, China was largely cast as the “sick man of Asia,” too weak and internally divided to pose a real threat, and “yellow peril” racist memes were relatively amorphous. That didn’t stop people like Wilhelm II of Germany from beating the idea like a war drum. At his instruction, the art history professor Hermann Knackfuss produced a lithograph in 1895 titled “People of Europe, Protect Your Holy Heritage!” It showed the archangel Michael, the symbol of Christianity, protecting the people of Europe, sword in hand, gesturing to the distant, ominous figure of the Buddha.

Of course, as ominous figures go, the Buddha is not a very good one, but Western powers would soon have a casus belli every bit as potent as 9/11 in the Boxer Uprising.

The Boxers, as historian James Carter explains, were a “variety of groups that had coalesced amid economic depression, ecological catastrophe, and foreign encroachment,” but their main rallying call was to “revive the Qing and destroy the foreign” (扶清滅洋 fúqīng mièyáng). They got their name because, to Westerners, their ritual movements looked similar to Chinese martial arts, then known as Chinese boxing. Another common term for their uprising, “Boxer Rebellion,” has fallen out of favor among historians because, Carter says, their “movement was, from its inception, in support of the ruling Qing dynasty, not rebelling against it.”

Reports of the Boxers carrying out pogroms against foreigners made Chinese seem menacing. Barbaric. Newspaper front pages told of the Taiyuan massacre in 1900, in which 45 Christian men, women, and children were gathered up and slaughtered — although as Carter writes, “Later scholarship…tends to blame mob violence.” There were also tales of the Boxers decapitating Catholic bishops, butchering missionaries and newlywed couples as they clung to each other, cutting out their victims’ hearts, and leaving their bodies to the dogs — see anthropologist Arnold Henry Savage Landor’s 1901 account “China and the Allies” to read about these and other events. To the West, the Chinese seemed incomprehensibly monstrous. After all, their Christian victims had only been trying to liberalize China, but the nation had only sunk deeper into barbarism. You can hear echoes of this narrative in talk about China today, but of course, the truth was more complicated.

For one thing, the Qing dynasty had earlier struggled to quell the Taiping Rebellion, which raged from 1850 to 1864 and left up to 30 million people dead, making it the bloodiest civil war in human history. The Taiping leader, Hóng Xiùquán 洪秀全, had claimed he was the brother of Jesus Christ. This badly damaged the reputation of Christian missionaries in China, who were already seen as instruments of Western imperialism and barely tolerated outside treaty ports, where they enjoyed special protection. And, while the Taiping rebels waged their war, Britain fought two wars of its own, killing tens of thousands of Chinese, so it could force opium on China. These wars ended with the first two “unequal treaties,” marking China’s subjugation to Western powers and the start of its “century of humiliation.” The treaties opened Chinese ports to trade and legalized both opium and Christian missionary work, which therefore both became symbols of Western cruelty.

As if this wasn’t enough, many Christians abused their newfound power, dodging taxes and harboring criminals to expand their numbers. As the historian Paul Cohen writes in History in Three Keys, Christianity spread by “absorbing people in need of protection from the law,” such that “the line between Christians and bandits became increasingly indistinct.” Some thugs even escaped arrest by claiming to be Catholic. Anti-Christian sentiment culminated in the Juye Incident of 1897, when 30 members of the Big Swords Society — farmers who defended villages from roaming bandits, warlords, and later the Japanese — stabbed two German Catholic missionaries to death in their sleep.

Soon, anti-Christian sentiment gave way to unbridled xenophobia and incidents of racist violence began to spread. The Boxers were fueled by the racist desire to purify China of foreign influence. Even the Empress Dowager Cixi herself had reason to fear the Boxers, since the ruling Qing were not ethnic Han but foreign Manchus. Still, she supported them to help fend off the coming invasion, and declared war against the Eight-Nation Alliance of America, Austria-Hungary, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and Russia. But in August 1901, the alliance reached Beijing, savagely plundered it, and forced China to sign the Boxer Protocol, one of the last unequal treaties. The Protocol called for the execution of all Boxers, as well as any who had helped them, and $10 billion in war reparations.

Because of the way it plays into racist and anti-imperialist frames that are relevant even to this day, the story of the Boxer Uprising has been told in different ways depending on who has been telling it. But one thing they all have in common is the tendency, whether they fall on one side of the aisle or the other, to look at it like a chessboard: black and white, zero sum, and resolved by checkmate.

The Boxer legacy reinterpreted, but never irrelevant

In China, the philosopher and diplomat Hu Shih (胡适 Hú Shì) criticized the Boxers for their racism and savagery. But they later came to be seen in a more positive light, as anti-imperialist patriots. The Chinese Communist Party, eager to push other forms of xenophobic messaging, has embraced them — Mao praised them — and when the historian Yuán Wěishí 袁伟时 criticized them in 2006, he was called a “race traitor.” The legacy of the Boxer Protocol and other unequal treaties has also helped China portray itself as the underdog as it asserts territorial claims on its periphery.

Outside China, some of the greatest minds of the day sided with the Boxers, foreshadowing the campism that now exists between “tankies” (communists or communist sympathizers) and democratic socialists who are too blinkered by their anti-imperialism to see that they’ve backed into stumping for Chinese imperialism instead. Indian intellectuals, including Rabindranath Tagore, had just witnessed the British use concentration camps to steal diamonds and gold from the South African Boers, and concluded the Boxers were therefore champions; Leo Tolstoy, who corresponded with Gandhi about resisting British imperialism in India, also wrote to Gū Hóngmíng 辜鴻銘, contrasting the “egoistic avarice and cruelty” of the West with the “wise tranquillity” of the Chinese; and Mark Twain fiercely satirized Western imperialism over the Boxer Uprising.

But the story of the Boxers has also fueled “yellow peril” thinking. The Russian philosopher Vladimir Solovyov, seeing the events in China, felt the country was inescapably authoritarian and that white Christians had to defend themselves against it. Meanwhile, the British philosopher Houston Stewart Chamberlain warned of a “Great Yellow Danger.” His writings would greatly influence German ethnonationalism, and would become such an inspiration to the Nazis that he would later be known as “Hitler’s John the Baptist.”

This is not to suggest that no moral clarity exists in the conflict between China and the West today, or that these forces are equally harmful. The point, rather, is that the portent of the “yellow peril” is very much alive, and that the storm surrounding the Boxers and their legacy never really passed.

This year in France, the newspaper Le Courier Picard featured an Asian woman in a mask on its front page along with an editorial titled “The New Yellow Peril?” Meanwhile, White House trade adviser Peter Navarro is still using the phrase “Chinese hordes” in his writing, and insinuating, without a shred of evidence, that China was intentionally “spawning,” and “seeding and spreading” disease to the world. And, of course, Trump himself continues to giddily repeat monikers such as “kung flu” because it gets a rise out of his supporters. And every time he does, the message is clear — they did this to us.

Next week marks the anniversary of the signing of the Boxer Protocol on September 7, 1901. It’s a good opportunity to consider the complexity of this passage in history, as well as how racism was used by both sides and continues to be used by both sides, from tankies and wolf warriors to Trump supporters. But, in particular, we ought to pay attention to how the “yellow peril” trope lives on, and manages to sway minds even though the argument itself has not become any more sophisticated. In fact, it’s just as blunt and vulgar as it ever was.