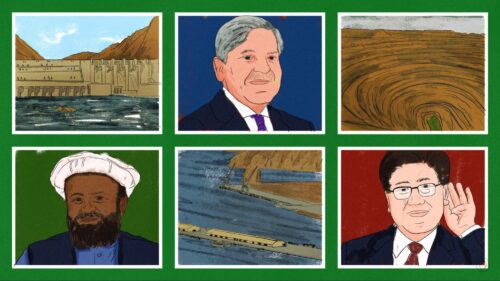

Is China turning Pakistan into a colonial outpost?

China and Pakistan call each other “iron brothers.” Some say Pakistan is China’s only real friend and ally in the world. But Pakistan might come to regret it.

On September 14, China and Pakistan sealed the deal on the 1,000 acre Rashakai Special Economic Zone (REZ). With heavy investment in electricity and gas power generation, this project came well-timed for Pakistan, which came close to declaring a national energy emergency in March. Meanwhile back in Beijing, Nóng Róng (农融), a trade expert, was appointed the new ambassador to Islamabad. And just this week, the Pakistan-Sichuan Chamber of Commerce (PSCC) was established in Chengdu, “to promote bilateral trade and open avenues of socio-economic partnership.” The two countries’ deepening economic ties, it appears, is a blessing for Pakistan.

But this blessing could be a curse in disguise. Although the “iron brothers” are embracing each other closer than ever, the power dynamic of this duo tilts heavily in China’s favor. Starting in 2013, China ostensibly came to the rescue of debt-ridden Pakistan by promising investment now valued at $87 billion via the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) — a network of roads, pipelines, and telecom infrastructure that connects China to Pakistan through Xinjiang. Envisioning nine Special Economic Zones (SEZs) and four mass transit projects, CPEC is part of the Belt-and-Road initiative, a trillion-dollar project under Xí Jìnpíng (习近平) that aims to promote land and maritime trade among over 70 countries.

But critics claim that China is issuing loans with opaque terms that do not abide by international lending standards. According to the Wall Street Journal, one concession from Pakistan promises Chinese power plants annual returns of up to 34% for 30 years. Worse, $35 billion of the CPEC is allocated for energy projects, which may receive state-guaranteed revenues at a ruinously high rate. Given that Pakistan already owes China more than twice what it does the IMF through June 2022, the feasibility of its debt repayment is alarming.

China is often accused of laying “debt traps” for countries like Pakistan, although economists dispute that China is intentionally using debt to extract concessions from poor countries. Nonetheless, when Sri Lanka failed to repay the Chinese loans it obtained to construct the Hambantota Port in 2017, it was forced to hand over 85% of equity in the port and lease 15,000 acres of land to China Merchant, a state-owned company, for 99 years. Although the agreement forbids military activity in the port, China nevertheless reportedly attempted to use its foothold for intelligence sharing. Nihal Rodrigo, a former Sri Lankan ambassador to China, told the New York Times that Chinese officials had insisted part of the deal was that, “We expect you to let us know who is coming and stopping here.”

An alternative route for trains, trade, and tanks

China’s investment in Pakistan has strategic considerations, too. It is deepening ties with Pakistan as its nervous neighbors shore up defense capabilities: For the year 2020-2021, India has allotted $65.86 billion to its defense budget (China’s stated budget is $178.6 billion), and the two Asian powers have this year intensified their long-running — sometimes violent — border dispute. After Alex Azar, the U.S. Health Secretary, visited Taiwan on August 10, Taipei secured an $8 billion F-16 fighter jet sale from the U.S. — its largest arms package since 1992. Japan’s defense spending hit a record high $48.5 billion for the fiscal year 2020. Australia, meanwhile, has been feuding with China over the national security law in Hong Kong, China’s retaliatory 80% tariff on barley imports, and recently the exit ban of two Australian journalists. In July, Canberra announced a new defense strategy that would deter countries that “pursue their strategic interests through a combination of coercive activities.” There is little doubt that China is its target.

Pakistan provides China with an alternative route for trains, trade, and tanks from the Chinese heartland to the Indian Ocean, which allows it to avoid the East and South China seas, and from the Strait of Malacca, through which the majority of China’s oil imports pass. Pakistan already granted a 43-year lease to China on its Gwadar Port, set to last until 2059. Satellite images of extensive security compounds there have caused speculation that China is on a path to convert the port into a naval base. Using Pakistani ports as springboards, China can bypass the pesky neighbors on its east coast and in Southeast Asia, and directly access the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Aden — vital waterways for maritime trade as well as naval operations.

Pakistani officials, including Abdul Razak Dawood, adviser to the prime minister, have warned of China taking “undue advantage” in the deal. But for now, Pakistan relies too much on China to back down. Its dwindling foreign reserves make Islamabad thirst for Chinese loans because its other potential lender, the IMF, prescribes austerity measures that could stoke domestic unrest. That explains Islamabad’s acquiescence in Beijing’s corruption: After an internal report in May indicted China for overcharging $2.5 billion for two coal-based projects, Imran Khan’s government refrained from publicizing that report. Instead, it postponed the inquiry and used it as leverage to delay repayment for up to 10 years.

Pakistan also needs China’s security assistance after America cut military cooperation in 2018. Challenges to Islamabad include various threats and strategic interests in Afghanistan; the Baloch Liberation Army (BLA), a separatist group that has repeatedly attacked Pakistani and Chinese targets in response to CPEC; and arch-rival India. New Delhi has riled Pakistan by declaring Jammu and Kashmir matters an “outdated agenda item” at the UN Security Council on September 2, and accused Pakistan of funding terrorist groups.

Old friend America, under President Trump, is not coming around this time. So Pakistan turns to its iron brother China for help, opening up its borders for Chinese money and tanks alike. It has gained short-term investment and a political shield from China — but at a damaging cost.