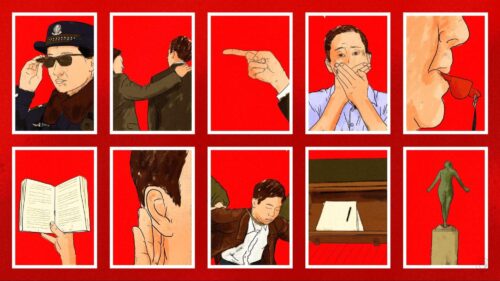

More than just censorship: How China shaped public sentiment in the early days of COVID

The Chinese government hired private companies to “flood social sites with distracting chatter,” among other tactics to tamp down public outrage during the worst parts of the coronavirus epidemic in China.

In the early days of the COVID-19 outbreak in China, a widely accepted narrative emerged that the epidemic was at least worsened, if not tipped out of control, by the government’s restrictions on speech. The death of Lǐ Wénliàng 李文亮, one of the doctors who was reprimanded for giving an early warning of a new virus, on February 7 crystallized public resentment about the relationship between censorship and the coronavirus outbreak.

Leaked documents reveal how worried Chinese officials became during that period, the New York Times reports, and what they did to attempt to claw the narrative back.

- Among “3,200 directives and 1,800 memos and other files” leaked from the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) and given to the NYT, one directive to local propaganda workers warns of a “butterfly effect” if the “unprecedented challenge” presented by news of Li’s death was not tackled.

- An earlier leak, of a report on “web users’ emotional response to the death of Li Wenliang and relevant recommendations,” was published in February by China Digital Times.

- Public opinion was so hot about Li’s case that authorities “had little choice but to permit expressions of grief, though only to a point,” the NYT says. Li’s profile on the social media site Weibo became a wailing wall of sorts.

Shaping public opinion means more than censorship, though.

- Private companies such as Urun Big Data Services were hired to “flood social sites with distracting chatter.” One district government in Hangzhou boasted that its fake posts had been read more than 40,000 times, “effectively eliminating city residents’ panic.”

- Even before Li’s death, as early as the first week of January, the NYT reports that the CAC had “ordered news websites to use only government-published material and not to draw any parallels with the deadly SARS outbreak.”

- Then, when the outbreak became worse, Chinese officials “tried to steer the narrative…to make the virus look less severe — and the authorities more capable — as the rest of the world was watching.”

For more on Chinese public opinion shaping, see a new report in ChinaFile: Message Control: How a new for-profit industry helps China’s leaders ‘manage public opinion.’

- The report draws from “3,100 procurement notices and corresponding documents, issued by both central and local governments.”

- One conclusion corroborates the NYT report: Rather than directly employing internet commenters, government offices are increasingly contracting out to private companies.

- In 2019, for example, the Beijing High People’s Court posted a procurement notice seeking the services of a veritable army of internet commenters:

The court’s procurement notice called for a vendor to provide 10,000 different Weibo accounts…and 20,000 different [accounts] on other websites…to appear to come from 10 different provinces and 40 different cities…with the ability to be posted from 70,000 different IP addresses that represented 15 different provinces.