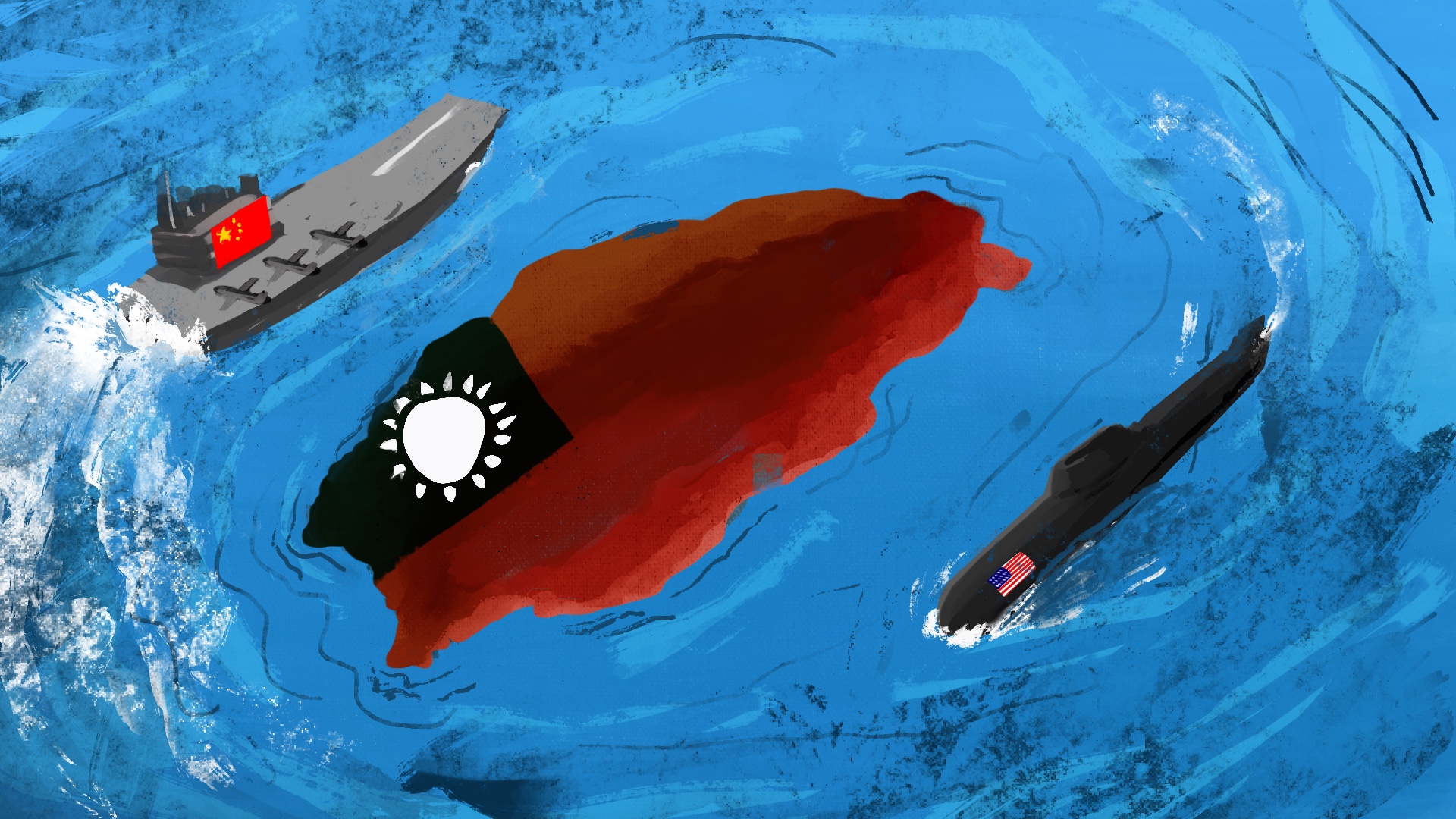

Pompeo’s 11th-hour announcement and the future of U.S.-Taiwan engagement

Is the outgoing Trump administration simply trying to complicate things for the president-elect?

On Saturday, outgoing Secretary of State Mike Pompeo released a surprise announcement: the U.S. executive branch, including the State Department, would no longer abide by its self-imposed restrictions on government contact with Taiwan. Those restrictions, which have evolved since the U.S. broke formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan in 1979, had been made to “appease the Communist regime in Beijing,” Pompeo wrote in a press statement. By Monday, the first known meeting that Pompeo’s announcement paved the way for took place in the Netherlands, when Pete Hoekstra, the American ambassador, hosted Chen Hsing-hsing, Taiwan’s representative to the Netherlands, at the U.S. embassy in the Hague. Chen said on Twitter she was “extremely pleased and honored” to have visited the embassy for the first time in her diplomatic career.

The Trump administration’s approach to Taiwan, the self-governing island claimed by China, has been norm-breaking from the start, when Donald Trump accepted a congratulatory call from Taiwan President Tsai Ing-Wen (蔡英文 Cài Yīngwén) before taking office — the first contact between a Taiwan leader and sitting or incoming American head of state since 1979. Over the past four years, the United States has ramped up public shows of support for Taiwan, including billions of dollars in arms sales and high-profile visits, most recently Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar’s trip last August. U.S. Ambassador to the UN Kelly Craft was scheduled to visit Taiwan this week, but her trip, like all State Department travel for the remainder of the Trump administration, was abruptly canceled on Tuesday. Instead, she met with President Tsai by video link on Wednesday.

“Executive branch agencies should consider all ‘contact guidelines’ regarding relations with Taiwan previously issued by the Department of State under authorities delegated to the Secretary of State to be null and void,” according to Pompeo’s announcement. “Additionally, any and all sections of the Foreign Affairs Manual or Foreign Affairs Handbook that convey authorities or otherwise purport to regulate executive branch engagement with Taiwan via any entity other than the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT) are also hereby voided.”

The timing of the announcement — less than two weeks before President-elect Joe Biden takes office — and the lack of details on implementation have raised questions about the overall effect it will have and how it might impact relations with China for both the U.S. and Taiwan.

“It’s a short announcement that nullifies existing contact guidelines but does not specify the scope of intended changes in practice or whether there will be any new Taiwan-specific guidance,” says Seton Hall professor Margaret Lewis, who is currently a visiting professor at Academia Sinica in Taiwan. It may hasten the Biden team’s need to articulate its policy on Taiwan and cross-strait relations, she adds.

As a senator, Biden signed the Taiwan Relations Act, but also spoke out on issues that China might view as provocative, such as closer U.S.-Taiwan military ties. Antony Blinken, Biden’s choice for Secretary of State, met with Pompeo on Friday, but it’s not clear if Saturday’s announcement was discussed. In a statement to the media, a transition team official said Biden supports the “peaceful resolution of cross-strait issues consistent with the wishes and best interests of the people of Taiwan.”

What will change, what won’t, and what remains unknown

The current predicament has roots from the past century. When the Chinese Civil War resumed in 1946 (after the two sides briefly allied to oppose Japan), the United States supported the Nationalist forces of Chiang Kai-shek (蒋介石 Jiǎng Jièshí) over Máo Zédōng’s 毛泽东 communists. By 1949, Chiang and the Republic of China government had fled to Taiwan, and the People’s Republic of China was established on the mainland. Both governments claimed jurisdiction over all of China.

The United States, fearing the spread of communism across Asia, supported the claims of Taiwan, which, while not democratic at the time, at least was not communist. By the 1970s, the ground had started to shift. The PRC took over the China seat at the United Nations from the Republic of China in 1971. Both sides initially nixed the concept of dual recognition, which would go against the concept each supported of a single China. (Since the 1990s, there have been initiatives for Taiwan to separately join the UN, but Taiwan is still blocked by China from joining the UN and other international organizations, making Craft’s conversation with Tsai especially symbolic.)

In 1979, after years of careful negotiation, the United States switched diplomatic recognition to the People’s Republic of China. Congress swiftly responded with the Taiwan Relations Act, which codified American support for Taiwan. That legislation, along with what came to be known as the Three U.S.-China Joint Communiqués and the Six Assurances to Taiwan, form the backbone of U.S. relations with China and Taiwan, allowing for unofficial ties to Taiwan while acknowledging the concept of a single China.

Those understandings have maintained a sometimes uneasy cross-strait peace for decades, though they have led to some unconventional accommodations. The Taiwan Relations Act called for the establishment of the American Institute in Taiwan, a nonprofit corporation established to carry out embassy-like functions in Taiwan (disclosure: I interned at AIT in 2019). The head of the institute is referred to as its director, rather than ambassador. When Taiwanese officials visited the United States, they met with government officials in hotels or other unofficial spaces rather than government offices.

“Lifting the internal guidelines is more than just symbolic,” says Lewis. “For example, the move opens the door to change which representatives of the Taiwan and U.S. governments meet and where they meet. Whether it will lead to a sustained increase in senior-level meetings will only be known as the Biden administration’s Taiwan policy takes shape.”

“Eliminating the guidelines does not mandate any changes,” adds David Keegan, who served as a foreign service officer in the State Department for 30 years was the deputy director of AIT from 2003 to 2006. “It just removes the current guidelines circulated around the bureaucracy to instruct them as to how to interact with Taiwan officials. That means that at what level to interact with Taiwan should still be up to the people in charge of China and Taiwan policy, but the elimination of the guidelines opens the way for freelancing, as we saw in the Hague.”

In one sense, then, loosening some of the self-imposed guidelines on contact between the U.S. and Taiwan is more in keeping with the reality of an increasingly close relationship. And the internal guidance — which was never legally binding — is constantly evolving and being revised. Some of the impetus for a review came from Congress, where Taiwan has strong bipartisan support. The 2018 Taiwan Travel Act “expresses the sense of Congress that the U.S. government should encourage visits between U.S. and Taiwanese officials at all levels.” The Taiwan Assurance Act, which passed as part of an omnibus bill last December, mandates a review of the State Department guidance on Taiwan.

But Pompeo’s terse statement seems to invalidate all existing guidelines rather than updating them, and it contains ambiguities. The most puzzling line in the statement is that “the executive branch‘s relations with Taiwan are to be handled by the non-profit AIT,” which seems to shift authority for Taiwan policy from the State Department — which coordinated on policy with other government agencies — to AIT. “Under the TRA, AIT is charged to implement U.S. relations with the people of Taiwan under the policy direction of the Department of State,” says Keegan. “Handing policy direction to AIT would be a dramatic change. How do you have a contractor setting policy?”

Much about U.S.-Taiwan relations — still officially unofficial — will remain the same. Further changes — such as updating the terminology used for Taiwan (which is never referred to as a “country”), allowing U.S. officials to enter Taiwan on government passports, or changing the visa status for Taiwan government employees stationed in the U.S. — are beyond the scope of the guidance. Such measures would likely destabilize the cross-strait situation, if it appears the U.S. is engaging in country-to-country relations with Taiwan.

“The Secretary’s statement speaks for itself,” according to a statement from AIT spokesperson Amanda Mansour. “Our longstanding one-China policy is guided by the Taiwan Relations Act, the Three Joint Communiqués, and the Six Assurances. Unofficial relations between the United States and Taiwan will continue to be conducted by or through the American Institute in Taiwan in line with the TRA. The recission of the State Department’s internal guidelines for federal government employee interactions with their counterparts from Taiwan does not affect our one-China policy, which remains in effect.”

Reactions from Taiwan and mainland China

For Taipei, the announcement may be seen as a parting gift from Trump, who is extremely popular on the island. “Trump is perceived as the most pro-Taiwan president,” says Eric Huang, a lecturer at Tamkang University and the former KMT spokesman. He finds the timing of the announcement largely political. “The GOP wishes to leave the Democrats with their anti-China policies, especially because the Biden administration is more risk-averse.”

Officials cheered the announcement. Joseph Wu, Taiwan’s minister of foreign affairs, tweeted from the ministry’s official account, “I’m grateful to @SecPompeo & @StateDept for lifting restrictions unnecessarily limiting our engagements these past years. I’m also thankful for strong bipartisan support in Congress for the Taiwan Assurance Act, which advocates a review of prior guidelines. The closer partnership between Taiwan & the United States is firmly based on our shared values, common interests & unshakeable belief in freedom & democracy. We’ll continue working in the months & years ahead to ensure Taiwan is & continues to be a force for good in the world.” The progressive, pro-independence New Power Party posted to its Facebook page that the party was “happy to see the continued warming of Taiwan-America bilateral relations.”

On the other side of the political spectrum, the KMT (the current incarnation of Chiang’s Nationalist Party and the main opposition to President Tsai’s Democratic Progressive Party) said on its website that it “looks favorably upon the improvement of relations.” However, the statement went on to say, “The DPP government must not become a bargaining chip for either the US or Mainland China…. More concrete, substantive, and persistent promotion of bilateral relations is necessary.”

Pompeo’s interview with Voice of America on Monday will do little to assuage concerns that the announcement had more to do with confronting China than helping Taiwan. He called actions taken over the weekend concerning Taiwan and Hong Kong “an important part of the strategy that we’ve laid out with respect to how to protect and preserve American freedoms vis the challenge that the Chinese Communist Party presents.”

Brian Hioe, a writer for New Bloom, an online publication focusing on activism and youth movements in Taiwan, raised concerns that Taiwan could become a partisan issue in the U.S., causing Democrats to shy away from support. “The Trump administration’s last-minute actions that purport to aid Taiwan could, in fact, be more dangerous for Taiwan than not,” he wrote on Sunday. “Though the lifting of American restrictions on contacts with Taiwan would unequivocally represent stronger U.S.-Taiwan relations if it was carried out under bipartisan auspices, moves by the Trump administration aimed at forcibly shifting the Biden administration’s China policy or simply aimed at frustrating the Biden administration could lead to antagonisms toward Taiwan.”

The reaction from China was more predictable. “We urge the U.S. side to abide by the one-China principle and the three China-US joint communiqués and stop elevating relations and military ties with Taiwan,” Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian said at a press conference on Monday. “We advise Mr. Pompeo and his likes to recognize the historical trend, stop manipulating Taiwan-related issues, stop retrogressive acts and stop going further down the wrong and dangerous path, otherwise they will be harshly punished by history.”

The Chinese government may hold off on responding too harshly, in hopes of establishing a better relationship with the Biden administration. But history also gives the U.S. a reason to avoid moving too fast, too soon on high-level visits with Taiwan officials. In 1995, Taiwan President Lee Teng-hui’s (李登辉 Lǐ Dēnghuī) visit to Cornell was a bit too presidential for Beijing’s liking, and soon after China fired missiles into the sea just north of Taiwan.

Meanwhile, American officials are confident that the legal and diplomatic maneuvers that have kept peace for decades will hold. “The United States has long maintained that cross-strait differences are matters to be resolved peacefully, without the threat or use of force or coercion, and should be acceptable to the people on both sides of the Taiwan Strait,” according to a State Department spokesperson. “There is no change in our position.”