China wants to ban ‘tainted’ celebrities, for good

Sex and drugs? No rock and roll for scandal-plagued actors and pop musicians.

The Chinese entertainment business used to love a comeback story.

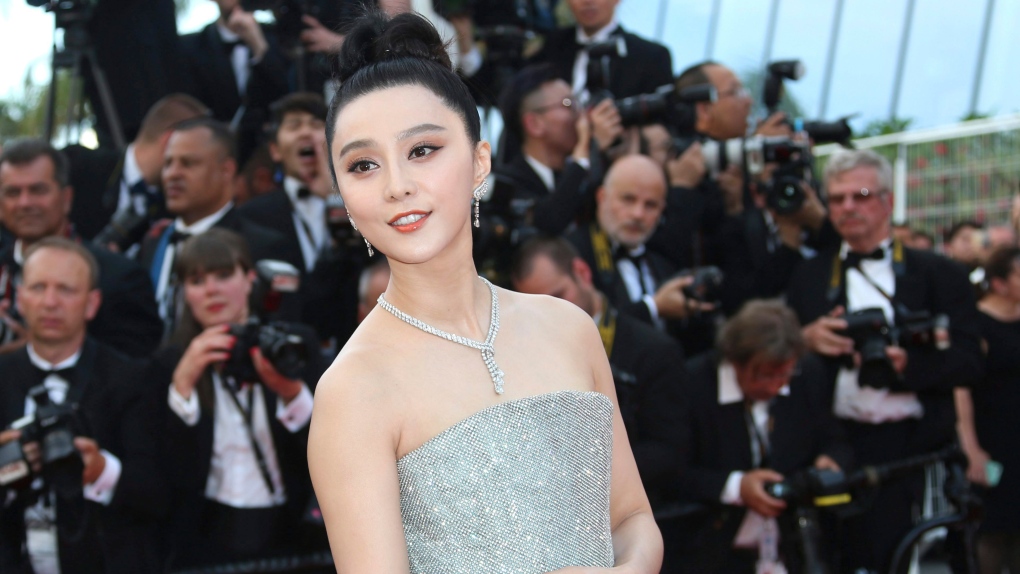

From tax-evading actress Fàn Bīngbīng 范冰冰 to drug-using singer Chén Yǔfán 陈羽凡, the industry is known for welcoming back scandal-plagued celebrities with open arms. After getting their names dragged in the mud, many stars have taken a hiatus from the limelight, eventually finding their way back onto the A-list.

But that’s about to change.

On Friday, the China Association of Performing Arts (CAPA), a government body under the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, for the first time released a raft of policies specifically targeting entertainers who look to make career revivals after committing offenses.

In a document (in Chinese) shared on its website titled “the Management Method of Professional Self-disciplining for Performers in the Entertainment Industry,” the association outlines four punishments for artists caught with “ethics violations,” including halting their eligibility for awards and subjecting them to “joint industry boycotts,” which could last a year or be permanent, depending on the severity of the circumstances and degrees of “negative social impacts” caused by their behavior.

It added that for those who want to return to the spotlight after their temporary bans end, they have to submit an application to CAPA’s ethics construction commission asking for permission to plot comebacks. The request should be made three months before the end date of their penalty term.

The wide-reaching document also includes a set of moral guidelines that cover various parts of artists’ lives, both onstage and in private. Aside from commonly known offenses like “harming national interests” and “disrupting China’s ethnic unity,” entertainers could face career restrictions for using physical defects to attract attention, endorsing products in advertisements that contain misleading information, or deceiving audiences in lip-synching performances. They must not promote religious groups deemed illegal by the Chinese government, endanger social morality, or criticize revolutionary heroes and martyrs, the notice stipulates.

When offstage, artists will find themselves in trouble if they take drugs, drive drunk, or engage in illegal activities that involve violence or obscenity.

The new policies will take effect on March 1 and apply to artists from various fields, including music, theater, dance, and opera. As China’s largest performing arts body, CAPA has offices in 31 provinces and nearly 10,000 members across the country, including performing venues, ticketing companies, and artist agencies, according to its website (in Chinese).

While it’s unclear how strictly the rules will be enforced, CAPA’s power to deter irresponsible behavior by artists is unquestionable. Soon after the notice was made public, a string of prominent state-run media outlets voiced strong support for the initiative.

“Every country has its own laws and every industry has its own regulations. When public figures lose their moral compass and neglect rules, they need to be called out and held accountable,” the People’s Daily wrote in a post (in Chinese) on Weibo. In another Weibo post, China Central Television, the country’s top state broadcaster, urged “high-profile celebrities” to be extra cautious about their behavior while commenting positively on CAPA’s policies. “One should educate themselves on morality before studying arts. One should learn how to be a decent human being before acting,” it wrote.

The initiative is hardly a surprise given that so-called “tainted stars” (劣迹艺人 lièjìyìrén) have long been a target of China’s broadcast regulators. Back in 2004, after a slew of Chinese celebrities were arrested on sex- and drug-related charges, media authorities ordered TV networks to ban troubled stars who have used drugs or visited prostitutes from TV and other media outlets.

But that ban was short-lived. In the following years, many entertainers have bounced back into the spotlight after getting bad press. They include Jackie Chan’s son Jaycee Chan (房祖名 Fáng Zǔmíng), who stepped back into his acting career in 2015 after being caught smoking marijuana in Beijing, and famed actress Fàn Bīngbīng 范冰冰, who disappeared for four months in 2018 amid a bombshell tax scandal that has rocked China’s entire film industry.

Many of these comebacks, however, were given the cold shoulder by critics, with many calling for industry insiders to stop giving a second chance to celebrities who committed something they thought was too terrible to forgive. Recently, in response to public anger over the phenomenon of scandal-stricken stars making low-key comebacks on livestreaming platforms, the National Radio and Television Administration proposed a ban against “illegal and immoral artists,” which was met with an outpouring of support on Chinese social media.