Xi Jinping is gaining support from Party elites, the numbers say

Judging by the voting history of NPC delegates, Chinese President Xi Jinping is enjoying greater support within the Chinese Communist Party now than ever. Whether that’s more attributable to coercion or genuine support is unknown, but either way, it’s evidence that Xi continues to consolidate his authority.

Reports on this year’s meeting of China’s legislature will inevitably describe the National People’s Congress (NPC) as a “rubber-stamp” parliament. This adjective seems fair for a nearly-3,000-delegate assembly that has never voted down a proposal. Yet the term obscures how approval margins change over time, in patterns that offer rare political insight. Recent votes suggest that China’s governing elite backs the sweeping policy agenda of current leader Xí Jìnpíng 习近平.

The full NPC meets in Beijing for only two weeks a year, coinciding with the plenary session of a political advisory body, in an occasion known as the “Two Sessions.” Delegates represent China’s provincial-level regions (or the military) and a supermajority are generally distinguished members of the ruling Communist Party. They gather to ratify personnel decisions, major legislation, and a number of annual work reports delivered by senior leaders.

Until the late 1980s delegates typically endorsed these items by “unanimous consent,” and majorities of 99% remain normal. But the introduction of “anonymous electronic voting machines” in 1990 helped encourage some legislators to express criticism by voting “no” or “abstain” on controversial issues. In 2013, for example, after air pollution in Beijing hit record levels, only 67% approved the name list for the new NPC environment committee.

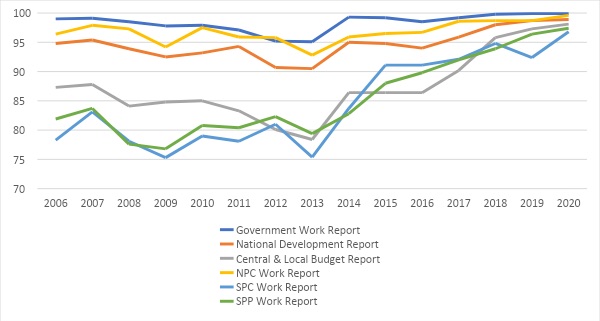

So how critical have NPC delegates been since they elected Xi as president in 2013? To answer this question, I charted the “yes” vote from 2006 to 2020 on the premier’s keynote government work report, the National Development and Reform Commission’s report on economic and social development, the Ministry of Finance’s report on central and local budgets, and the work reports of the NPC, Supreme People’s Court (SPC), and Supreme People’s Procuratorate (SPP).

NPC voting approval rates for official reports (%)

The graph shows marked improvement in the approval rates of all six reports since Xi succeeded Hú Jǐntāo 胡锦涛, who was president from 2003 to 2013. This movement is especially clear for the three most contentious reports — one on budgets and two on law enforcement — which reportedly struggled due to perceptions of fiscal mismanagement and pervasive complaints about judicial corruption and poor legal protections for business. But even the most politically sensitive vote, on the government work report, sees a noticeable uptick.

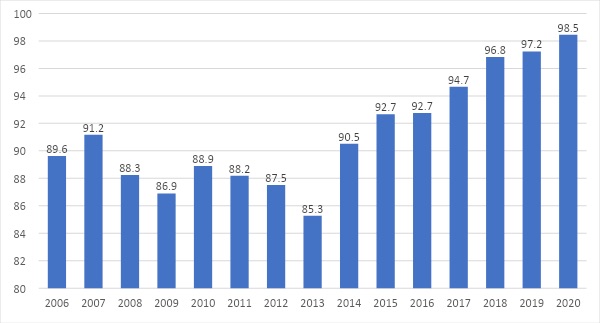

The upward trend becomes plainer if we plot the average annual “yes” vote. Overall approval of the government’s activities gradually declined over Hu’s second term as president, falling from 91.2% in 2007 to a low of 85.3% in 2013. Since Xi became president that year, this “yes” index rose every year and hit a 15-year high of 98.5% at the COVID-delayed NPC of 2020.

Average NPC voting approval rate for six major reports (%)

Lukewarm support at the NPC is an unusually public expression of disapproval in the Chinese system, which may weaken an administration ’s ability to win policy compliance throughout the Party’s vast political apparatus. And while these work reports are delivered by lower-ranked figures, it’s paramount leaders like Xi and Hu who must bear ultimate responsibility.

Xi’s strong showing is significant because it implies that his platform enjoys wider support, or at least broader acquiescence, among Party elites. Before Xi, Hu’s lower tallies likely reflected concerns that his “collective leadership” failed to control the harmful externalities of rapid growth, especially inequality and pollution, and allowed corruption and indiscipline to flourish in the cadre ranks, threatening the Party’s grip on the country.

After Xi took office, he overhauled the forms and norms of Chinese politics to concentrate power in himself as the “leadership core,” centralize decision-making in Party institutions, and curb resistance to effective policy execution. In his judgment, enhanced control is necessary to implement an ambitious reform agenda to revitalize Party governance, with the overarching aims to improve living standards, increase national power, and bolster regime legitimacy.

Claims that Xi’s authoritarian renaissance sparked a backlash from political rivals and civil society are correct, yet there’s little sign of opposition in the actual corridors of power. Indeed, the NPC data adds weight to theories that “Xi’s rise” is as much the result of a collective response to crisis as it is an individual will to power. Rising “yes” votes indicate that Xi’s dream to “make China great again” may be more popular in Beijing than is sometimes assumed.

Of course, another explanation for why more NPC delegates approve government reports under Xi’s leadership is that they might increasingly fear personal repercussions if they do not cast an assenting vote. Election regulations stipulate anonymity, and the NPC electronic voting system’s state-owned manufacturer insists on it. Delegates, however, complain that colleagues can easily see how they vote, and even Chinese media note the possibility of back-end decryption.

In 2010, Jiāng Píng 江平, a prominent legal scholar, said an NPC insider told him that the electronic voting technology was designed to allow for voter identification, if requested. After one NPC, leaders supposedly confronted Liào Huī 廖晖, the son of a revolutionary cadre, when they discovered he was the delegate that opposed every item on that year’s docket. (Liao, who became a high-ranking official in Hong Kong affairs, retired in 2013.)

It’s hard to know for certain, but it seems likely that both genuine support and greater control explain the NPC’s higher approval of government reports during Xi’s leadership. Either way, the fact that more NPC delegates choose or feel compelled to approve everything that Beijing does is a real sliver of evidence that Xi continues to consolidate his authority within the Party.

This backing bodes well for Xi at this year’s Two Sessions, as his government unveils the next Five Year Plan for national development and a special 15-year vision for China to substantively attain great power status by 2035. Whether this program succeeds could well end up determining if China’s parliamentarians continue to give him their stamp of approval.