Regularly voted the most beautiful woman in Chinese history, Lín Huīyīn 林徽因 was one of the most scintillating stars of the Republican era. Her love life has been the subject of countless books and TV shows, but leaves her overshadowed by the men she was attached to: romantic poet Xú Zhìmó 徐志摩 and Liáng Sīchéng 梁思成, “the father of modern Chinese architecture.” But Lin deserves to be recognized in her own right, as the gifted writer, actress, architect, and salonnière she was.

Who is Lin Huiyin?

Lin had been given a head start from an early age: due to the wealth of her family she was given an education, a rarity for women in the early years of the Republic. Her father was Lin Changmin (林长民 Lín Zhǎngmín), a prominent Republican politician who believed in equal education for women. She was taken with him to London in 1920 for further education when he became director of the Chinese Association for the League of Nations. It was here that she met Xu Zhimo. (Xu’s mentor, Liáng Qǐchāo 梁启超, introduced him to Lin Changmin in the summer of 1920.)

Although many stories celebrate the romance of two beautiful and bright young stars of the glamorous Republican era, it’s worth pointing out that Xu already had a pregnant wife at the time, who he treated with deep disdain (due to her traditional beliefs) and abandoned in Cambridge. He would travel from Cambridge to London almost every other day to take tea with the Lins and engage Lin Huiyin in intellectual discussion, the two writing almost every day. She became one of his poetic muses, with Xu even divorcing his first wife — celebrated as the first modern Chinese divorce — in the hopes of marrying her.

The romance was cut short by Lin returning to China with her father in 1922. She had confessed to her father these strange (and perhaps shameful) feelings of love for an older married man, resulting in Lin Changmin writing to Xu telling him politely but firmly to back away. She had been promised to Liang Sicheng, Liang Qichao’s son.

Lin and Liang went to live in America in the spring of 1924, shuttling from university to university. Lin was determined to learn architecture, but was turned away from the architectural department at the University of Pennsylvania because she was a woman. But she managed to find a way to work as a part-time assistant in the architecture department by taking a course in the School of Fine Arts. Not only did she do all of her four-year coursework in three years, but she also became a part-time instructor in architectural design. Slowly, the couple learned Western architectural practice, aspiring to incorporate new building techniques with Chinese architectural tradition, both modernizing the old and familiarizing the new. As Lin put it in an interview with the Philadelphia Public Ledger, they wanted to house “Chinese spirit in modern strength.”

After a brief stint teaching at Dongbei University, the couple returned to Beijing in the early 1930s. No longer the capital, it was now just a city of immense cultural significance, motorcars and camels jamming its dusty streets, beyond which lay the charming tranquility of courtyard houses. They set up shop at No. 3 North Zongbu Lane, frequented by all sorts of high-flying intellectuals who would be treated to tea and the finest academic discourse. This was usually led by Lin, a vivacious and attractive hostess. American Sinologist and regular guest John K. Fairbank wrote that “the household, or any scene she was in, tended to revolve around her.”

Lin was a fine writer, her poems, short stories, and plays appearing in national newspapers. She was, according to poet Xiāo Qián 萧乾, the “soul of the Beijing School,” a collection of modernist writers (like Shěn Cóngwén 沈从文) who shunned commercialized writing, focusing on tradition and life in rural areas. But for Lin, this wasn’t enough — literature should reflect the changes in society, and highlight friction points. In 1936 she wrote in a preface to an anthology of the school’s work that “few in this collection attempt to depict the bold fragments of life” or to dissect “the contradictions in everyday life.”

Her answer was “Ninety-Nine Degrees,” a short story not unlike Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, the narrative flitting from character to character, a stream of consciousness from a cross-section of society in inter-war Beijing, set in one hutong on a scorching hot day. As pointed out by Song Weijie in her essay “The Aesthetic Versus the Political: Lin Huiyin and Modern Beijing,” “the omniscient narrator raises the curtain on the disorderly everyday life of modern Beijing so as to feel the city’s pulse and diagnose its symptoms.”

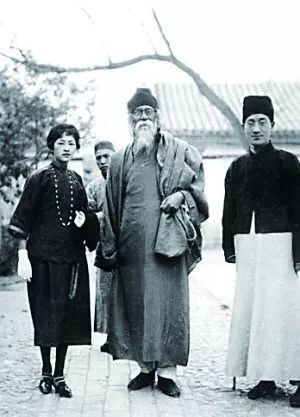

She was also a key figure in the Crescent Moon Society, planning its activities alongside Xu Zhimo, like welcoming the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore when he came to China in 1924, Lin serving as his translator. She took the title role in his play Chitra, a tale of an Indian warrior princess. A captivated Tagore wrote a special poem in her honor: “The blue of the sky fell in love with the green of the earth. / The breeze between them sighs ‘Alas!’”

Lin and Liang were dedicated to preserving the old, when so much around them was changing. Aside from city life, they voyaged into the wilderness to uncover and document relics of previous centuries, following Western practice that architecture was best studied from field trips. They were often led by the vaguest of sources, like a cave painting or scrap of text, Lin likening it to “a blind man riding a blind horse.”

But they were especially successful in Shanxi, a poor backwater where many ancient buildings had escaped the scourges of time. She and her husband would travel by foot, mule, and rickshaw in their searches, charting the evolution of Chinese architecture as a reward for their long journeys. Writing in a letter on a trip there in 1934, Lin marveled how, “In the past ten days everything I’ve seen is a picture, and everyday an ancient tale to be sung and recited…In order to visit ancient sites we have walked a lot and are moved by the rise and decline of the past and the present. Reading inscriptions on the tablets buried in wild grass, or coming across a Buddha’s hands or smile amid a brick pile — all of these stimulate uncommon feelings.” They discovered that the remote Foguang Temple was the oldest wooden Tang structure in the country, with a building style that had only previously been known from books.

They also surveyed Beijing itself, charting thousands of ancient sites. According to Wilma Fairbank (wife of John Fairbank), the couple viewed Beijing as a “gigantic exhibition hall,” Lin recording in her writings that it was an “organic museum.” Every building had its measurements and position dictated by a central planning authority under the emperor, all radiating out from the main trunk of the central axis, a north to south line with the Forbidden City at the center. Even the smallest structure was a part of the whole.

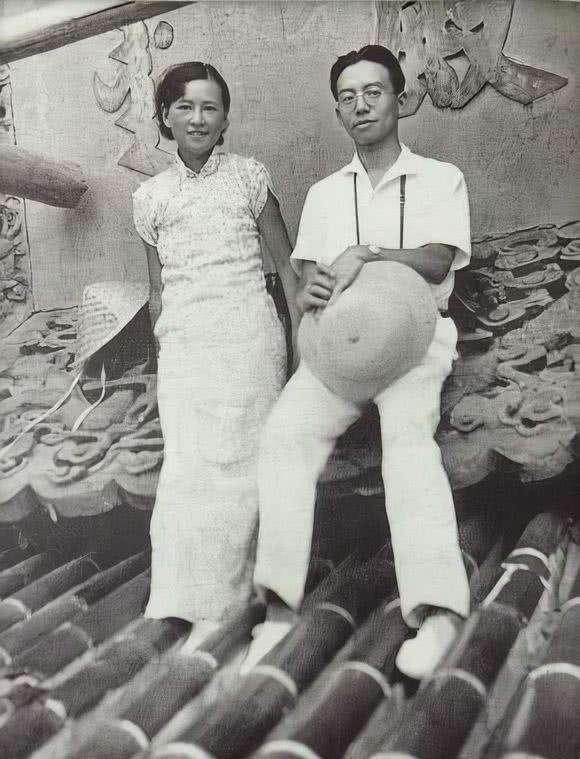

The pair would scale all sorts of buildings during restoration work, intent on documenting ancient styles and building techniques. But although Lin would help her husband write their famous History of Chinese Architecture and worked alongside him in architectural teaching, there aren’t many buildings designed under her own name. The ones she did design were unglamorous, like a railway station in Jilin or a female dormitory at Peking University.

But perhaps she is due more credit. According to Wilma Fairbank, the couple worked on designs as a team: “Lin Huiyin, full of creative ideas, would start to draft a plan or elevation…[Liang] Sichang would step in and reduce the frenzied product to a clear finished presentation.” According to Harold Kalman, their son Liáng Cóngjiè 梁从诫 believed the majority of the buildings assigned to Liang were actually Lin’s creations.

1937 caught them by surprise. They heard about the outbreak of hostilities with the Japanese eight days after it happened, having gone deep into the Shanxi countryside in search of an ancient monastery. For several years the two moved their family from city to city, often taking time to document the ancient buildings of the places they passed through, all while Lin was wracked with consumption. In 1948, the Communists came to visit the two with a map of the capital, asking them to pinpoint any sites of cultural value and heritage, which would be avoided if it came to street battles with the Kuomintang. This immediately won the two over to the Communist cause.

And it did seem good to begin with. The two were given prestigious jobs at Tsinghua University, Lin joyfully reviving her soirees there. By the early ’50s she was a member of the Committee of Beijing Urban Planning, the Team for the National Emblem Design, and Committee for the Design of the Monument to the People’s Heroes, a representative in Beijing’s first People’s Congress and a member of the National Literature Assembly. Together with her husband, they designed the Monument to People’s Heroes that stands at the center of Tiananmen Square. They also created the new national emblem of China, chosen in a competition by Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 and Zhōu Ēnlái 周恩来 — it featured a cog wheel and ears of wheat to symbolize the workers of the nation, along with Tiananmen Gate, the site of the May Fourth student uprising that had paved the way for the new China.

It seemed as if the Communists had great respect for the city. The municipal authorities boasted that during their great clean-up of the city in 1949 and 1950, they emptied 330,000 tons of rubbish that had built up since the Ming. The streets had never been so clean.

But then the destruction started. “We’ll see a forest of chimneys from here!” Mao had supposedly said to the city mayor Péng Zhēn 彭真 as they stood on the rostrum on Tiananmen Gate. The stagnant moats around the city walls, flanked by neighborhoods notorious for immorality and vice, were filled in. Poky little shanty towns began clogging up the courtyards.

But perhaps the worst for Lin was the planned demolition of the city walls — to the government, they were a reminder of feudalism and an obstruction to expansion. To Lin, they were an irreplaceable jewel and integral part of the Beijing skyline. She and her husband suggested building a new city to the west and leaving old Beijing as it was. Lin also mooted planting a park along the old battlements, aware that cities in industrial areas needed green spaces for community and individual wellbeing, roots to the past so essential that she predicted people would eventually create “fake antiques” once they realized the worth of the originals they’d destroyed. But she was ignored.

Lin died in 1955, while her husband would go on to be criticized during the Cultural Revolution. Her tombstone was desecrated by Red Guards because she had dared to preserve the old. But today, perhaps her call for humanity in a choking city is being heard — in an August 2020 announcement, China’s State Council declared that a park would be created around the Second Ring Road, where the city wall once stood, to showcase “the historical and cultural landscape” of the modern capital. Far better to have kept the wall in the first place, like Lin had suggested.

Chinese Lives is a recurring series.