Documenting China’s U.S. Capitol-inspired buildings

Starting in June 2019, photographer Wu Guoyong began traveling across China to piece together a strange collection of photographs: buildings inspired by the U.S. Capitol Building. He calls the series "China's White House."

It’s late 2019 and Hubei-native Wú Guóyǒng 吴国勇 is road-tripping around Hunan province in the company of friends. From the Yuanjiang wharf, a rustic fishing junk is hired, a poster of Chairman Mao fastened to the cabin wall. Some people burn coals in the center of the vessel to provide relief from the damp, winter air, even if the logic of an open fire on a wooden vessel is questionable.

Travel in China can often feel like a journey through time. Sailing along the shoreline of Dongting Lake — which separates Hubei (North of the Lake) from Hunan (South of the Lake) — we are transported across eras via the changing architectural styles: gargantuan Mao-era factories, a haunting Ming pavilion, and rows of reform-era tenements occupying the prime waterfront location that the high-rise towers of New China are fast encroaching upon.

“All styles of architecture tell a story,” Wu says.

After the boat trip, we head south to our next destination, the prefecture-level city of Loudi. Wu pulls up at a nondescript location and begins setting up his camera and tripod.

“What are you photographing?” I ask.

“That building,” he says, gesturing ahead. “It’s for a new series I’m working on.”

When I inquire, Wu replies, “American architecture.”

Bemused, I look at a gate guarded by two traditional stone lions before a municipal government building, the kind of imposing office block one sees everywhere in a country with as many civil servants as Sweden has people. Nothing appears out of the ordinary. Yet beyond a big character sign urging “cadres to take the lead,” I see what Wu’s talking about, an edifice utterly distinct from the identikit apartment buildings of a city situated in the very heart of a landlocked Chinese province. It’s the American Capitol Building.

Born in 1963, Wu has witnessed Sino-American relations ebb and flow like a tidal bore in the Yangtze River. “When I was young, we learned anti-American songs,” he recalls of his early years when the Cultural Revolution was in full swing.

Although he vaguely recalls Chairman Máo Zédōng’s 毛泽东 meeting with President Richard Nixon in 1972, it wasn’t until Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平 donned a cowboy hat in 1979 that Wu sensed the winds of fortune were changing. “When we entered the era of reform and opening up, everyone was encouraged to learn from the West. It was like a mantra of the age.”

Although “the West” comprises many countries, for people of Wu’s generation, the artist believes the word implied one country above all else: Měiguó 美国 — the Beautiful Country, as the U.S.A. is known in Chinese. “We all thought about the U.S. Everything from the movies to music was feeding our collective imaginations.”

Nowhere was Americana more evident than in the southern boomtown of Shenzhen, where Wu moved in 1992. “Shenzhen was born out of the reform era,” he says. “It’s such an interesting city in this respect. It faces outwards, its growth driven by manufacturing and financed by international trade.”

Tellingly, the Special Economic Zone was where the most potent image of global America made landfall in 1990: China’s first branch of McDonald’s, which opened in Dongmen, Luohu district, and still serves Big Macs today.

Wu’s career as an engineer developed in concert with Shenzhen, a city that boasted the fastest growing urban economy in a country that was counting double-digit GDP growth as the norm.

In 2011, Wu retired early, at the age of 49, to focus on his passion for photography. He honed his craft as a landscape photographer until some local artists like Lǐ Zhèngdé 李政德 schooled him in art photography. A few years later, in 2018, Wu shot to fame with No Place to Place, an arresting series of images that documented China’s bicycle graveyards from the aerial vantage point of a drone.

Accolades and exhibitions around the globe soon followed as Wu enjoyed the kind of recognition many of his contemporaries could only dream of. But such success complicated a follow-up project, that “difficult second album” musicians talk about.

When COVID-19 emerged in his home province last year, Wu co-curated the project “One Thousand Families” while locked down in his Shenzhen apartment. But inspiration for a solo sophomore series had come months before, when he was sorting through old pictures he’d taken in Shenzhen in the 1990s.

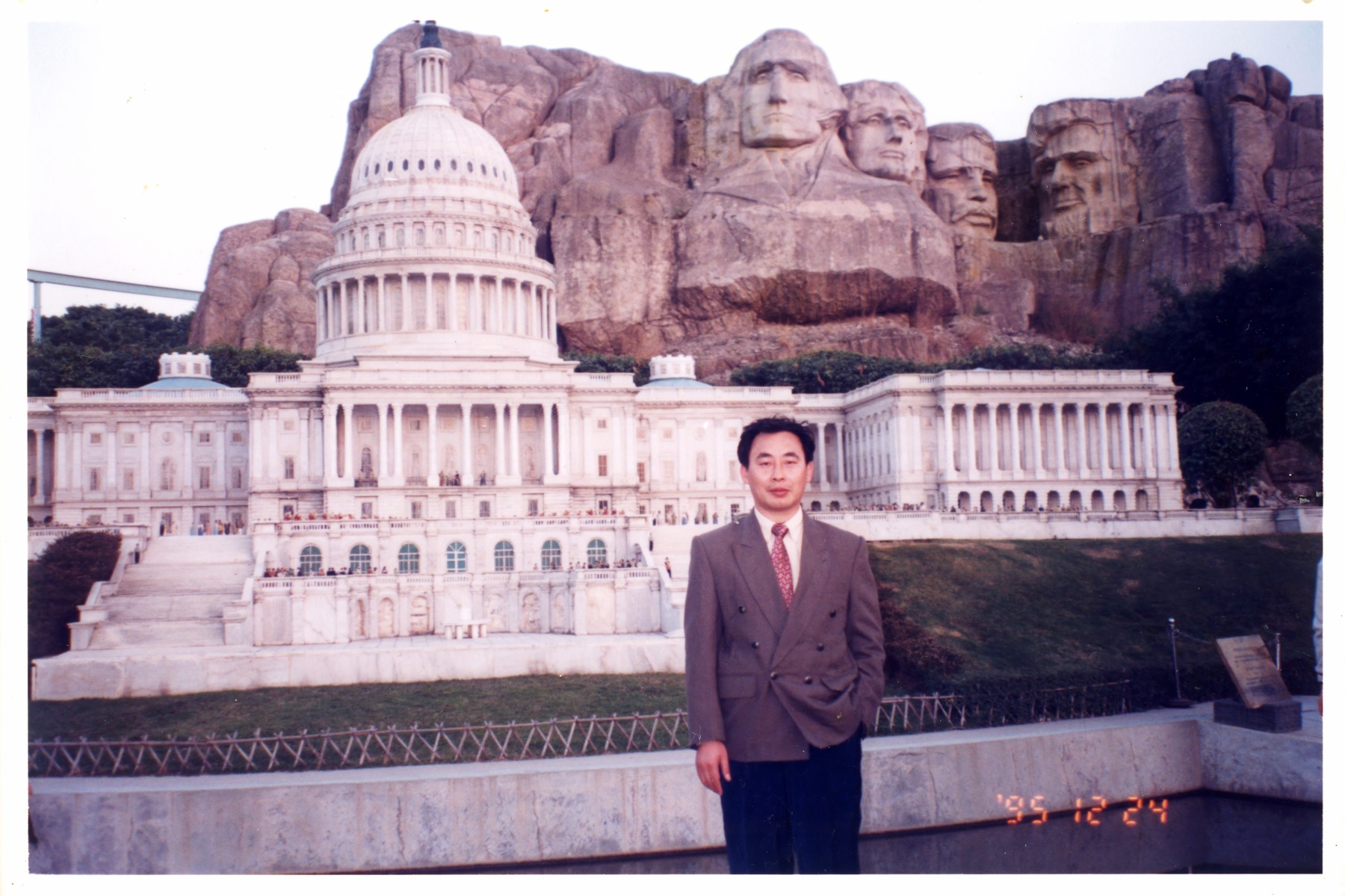

“I visited the Window of the World a few times in the 1990s,” Wu says of the theme park opened in 1993 in Nanshan district that is home to scaled-down versions of various architectural icons, including a mock Eiffel Tower, a Palace of Westminster, and the Pyramids. Some view the theme park as ersatz, though Wu sees it in less critical terms: “It satisfied the desires for the vast majority of Chinese who didn’t have the opportunity to travel.”

While sorting through old photos, one image in particular sparked his imagination: a model of Mount Rushmore overlooking a replica of the U.S. Capitol Building, taken when he visited Window of the World in 1995.

“I think I noticed it because the U.S. was in the news a lot due to the trade war,” he says.

Chinese versions of Western architecture are nothing new. During the boom years from 2000 onwards, whole towns were built amid an occidental vogue, including Thames Town in Shanghai and Little Italy in Shenzhen, which was named Portofino after the Italian seaside town.

This fad for Western architecture has since ended. In 2014, President Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 criticized the construction of “weird buildings”; more recently, “Western-sounding names” of buildings throughout China have reportedly been changed. But in 2019, after Wu noticed one Capitol replica in an old photo, he started to see such buildings everywhere.

“With the opening of the country, the U.S. Capitol, elegant and associated with power, soon became a paradigm that buildings all over China rushed to imitate,” Wu says.

As he did when documenting bicycle graveyards, Wu decided to pursue his curiosity nationwide, traveling from village to city and from north to south starting in June 2019, piecing together a startling, and strange, collection of photographs. He’s shot everything from luxury hotels to municipal courthouses, university libraries to public restrooms — buildings all tied together by their similarity to a certain Washington, D.C., structure. He calls the series China’s White House (中国白宫 zhōngguó báigōng).

“A lot of Chinese can’t tell the difference between the White House and Capitol Building,” Wu notes. “Both are referred to as the ‘White House.’”

As to why there is such a propensity of derivative D.C. structures, Wu cites several reasons. “In the early days there was a lack of cultural self-confidence and a fetishizing of foreign things,” he says. “But I also think they reflect the honeymoon period of Sino-American relations during the early reform era.”

As “White House architecture” became more prevalent, “Courts adopted the dignified and symmetrical appearance of the Capitol Building as it coincides with the court’s image of fair and just law enforcement. Universities believed that through these types of buildings students could better understand world culture. Many hotels have chosen the shape of the White House in order to attract more guests with its fancy look.”

Some people have gone full hog in applying White House aesthetics in order to cultivate business.

“There’s a public restroom in a winery in Fuyang, Anhui province that has gained publicity for its White House look. The owner of the distillery says people come from all over the country and the first thing they do is find the toilet.”

Wu also notes how aspirational landowners will build private property in the White House style. “Xǔ Níng 许宁, a farmer from Hainan, grows betel nut and rubber. But having seen a photo of the Capitol Building, he built a villa on his family’s ancestral hillside in the same style, causing a sensation and creating a local landmark when it was completed in 2008. He’s even become an internet celebrity, known to netizens as the White House Farmer.”

However, as China’s confidence buoys in tandem with its economic growth, White House architecture is becoming passé. Some buildings, like Beijing’s Geely College, are having their domes removed to distance themselves from the American model they once imitated.

“Since being acquired by Peking University as their Changping campus, the roof is being remodeled,” Wu says.

Many other White Houses have fallen into neglect, dilapidated and abandoned, and await demolition. Yet in these forgotten relics of the reform era, Wu reads the latest twist in the plot.

“In 2013, a private investment company started building the Great Wall Cultural and Creative Park in Shijiazhuang,” Wu says of Hebei’s answer to Window of the World. “But construction stopped long ago. The centerpiece was a model of Beijing’s Temple of Heaven merged with the White House overlooking an empty park.

“That sort of represents Sino-American relations currently.”