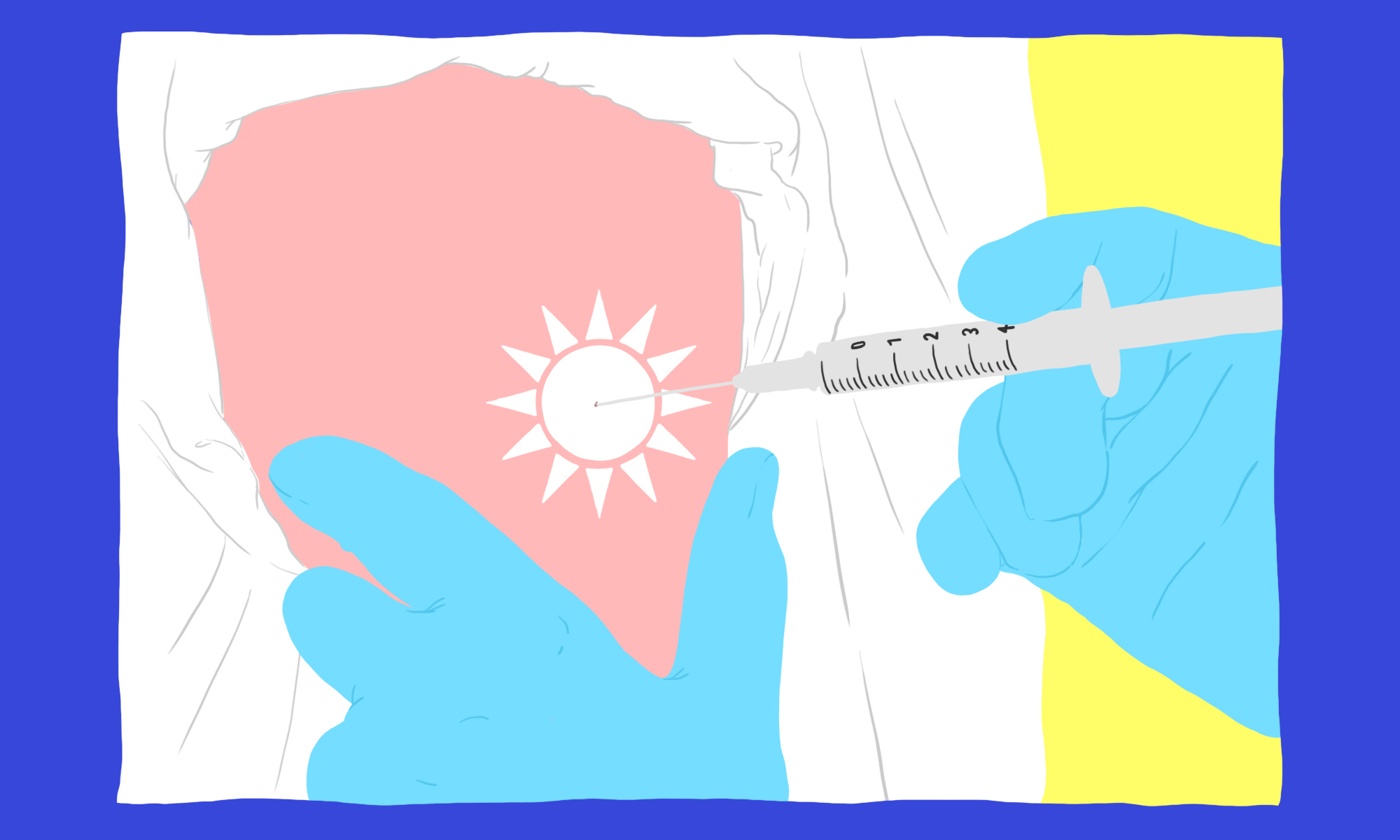

The politicalization of COVID vaccines in Taiwan

A recent outbreak of COVID-19 in Taiwan has exposed flaws in the government’s pandemic response plans. While the ruling Democratic Progressive Party attempts to get things under control, its political enemies are circling.

After going more than 200 days at one point without a locally transmitted case of COVID-19, Taiwan has found itself gripped by an outbreak. Starting from May 15, when 180 locally transmitted cases were announced and the Taipei metro area was put on partial lockdown, there have been over 9,000 cases on the island and more than 300 deaths, a shock to a public that perceived itself as having defeated the virus.

Though these numbers may seem small compared to most countries, the current situation is threatening the Taiwanese political status quo. President Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文 Cài Yīngwén) and her ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) are being blamed for the virus’s spread and for being unprepared. The pandemic has created opportunities for opposition parties that a month ago seemed impossible.

According to Chang Hong-ren (张鸿仁 Zhāng Hóngrén), a professor and former director of Taiwan’s Center for Disease Control (CDC), the government clearly “became a victim of its own success.” Its strategy since January 2020, when it became clear that COVID-19 was spreading outside of China, had been focused on erecting a fortress around Taiwan that would prevent the virus from entering its borders. Chang says that this worked so well that authorities failed to prepare for the possibility of a community spread event, meaning that they did not prepare a lockdown policy, isolation units in hospitals, a testing strategy, or purchase large quantities of vaccines, leaving the island unprepared for what has transpired.

Due to fears of economic repercussions, the government is extremely hesitant to institute a strict lockdown. Only a mass vaccination program will be able to reduce the virus’s spread, Chang believes.

But can the DPP deliver? The government’s approval rating has recently dipped. A May 27 TVBS poll found that 80 percent of people were unsatisfied with President Tsai, and 75 percent were unsatisfied with Minister of Health and Welfare and epidemic control center commander Chen Shih-jong (陈时中 Chén Shízhōng), who as recently as late April had an approval rate of 66 percent.

The political landscape has re-centered itself around the question of vaccine procurement. With only around 300,000 vaccine doses administered before May 15, covering just over one percent of the population, one of the lowest vaccination rates in the industrialized world, critics claim the Tsai government has failed in protecting Taiwanese citizens’ health.

According to Kharis Templeman, a researcher at Stanford’s Hoover Institute, vaccine procurement could become a “potentially pretty fraught issue” for the Tsai government, with the lack of vaccines representing “a big vulnerability.” The two opposition parties, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taipei mayor Ko Wen-je’s (柯文哲 Kē Wénzhé) up-and-coming Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), have both wielded this issue to attack the government.

A May 25 KMT press release read: “The government has failed to put in place relevant measures to counter the rapid rise of community infections, nor has it strived to increase COVID-19 testing capacity.” With a massive shortage in vaccines, KMT-controlled local governments and charitable organizations have begun attempting to buy their own vaccines, entering into procedural conflict with the central government. Additionally, when the epidemic command center revealed that of the 14 million doses to be administered by the end of August, 10 million would come from domestically produced vaccines, which have just finished stage 2 clinical trials, various KMT officials accused the government of inflating the domestic vaccine industry’s stock prices. President Tsai later stated that an internal investigation found no signs of corruption, but the KMT holds that Tsai “wanted our prosecutors to steer clear” of the case.

Beginning on June 3, the KMT organized car protests in front of the Presidential Office Building. One of the first organizers, Taipei city council member Wang Chih-bing (汪志冰 Wāng Zhìbīng), says that she began organizing protests because the Taiwanese public “are still waiting for vaccines. Everything else is useless.” She believes that the government has failed in protecting the Taiwanese public, allowing the virus to creep into Taiwan’s borders and wasting the 15 months of time Taiwan had to prepare for a community spread event. Additionally, Wang believes that the Taiwanese public will shy away from the local vaccine because it has “no foundation of credibility.” Now, Tsai and epidemic commander Chen have shown that they are “rotten eggs that must be replaced.”

“The government response’s greatest deficiency is that it can’t buy effective, internationally recognized vaccines,” says Chiu Chen-yuan (邱臣远 Qiū Chényuǎn), a TPP member of the Legislative Yuan, Taiwan’s parliament. “Why should we rely on these [local] vaccines when there are already numerous ones that have international recognition?”

Inevitably, vaccine procurement has become a diplomatic issue. Beginning late last year, after China’s Sinopharm vaccine began being distributed around the world, Chinese authorities expressed a willingness to sell vaccines to Taiwan. Legislators from the KMT as well as members of the press began asking Chen Shih-chung, the leader of the pandemic response, why the government had not bought vaccines from Beijing. Chen answered that he feared the public didn’t trust Chinese vaccines, and that Taiwanese law banned the import of vaccines from the mainland, meaning only a change in the law by the legislature, which is dominated by the independence-leaning DPP, would make that possible. On June 11, Ma Xiaoguang (马晓光), spokesperson for China’s Taiwan Affairs Office, invited “Taiwanese compatriots” to come to the mainland and get vaccinated, indicating that 62 thousand Taiwanese already had.

The controversy with BioNtech, which developed and produces the vaccine sold by Pfizer, additionally revealed how difficult it is for the DPP government to deal with anything related to China, even for an issue as pressing as vaccines. According to the government, a deal to purchase millions of doses fell through because the two sides reportedly couldn’t agree over how to refer to Taiwan in a press release — though it is unclear if Fosun Pharmaceutical, the private Chinese company that has the right to sell the vaccine in Taiwan, was involved. According to Chang, the former public health official, the necessity of receiving approval from both Biontech and Fosun means that the chances of purchasing BioNtech vaccines are slim. Changing the law to allow the import of mainland Chinese vaccines is an even more remote prospect.

Templeman, the Stanford researcher, says that in contrast to purchasing Chinese vaccines, the Tsai administration has chosen to rely on its strong relationship to Japan and the United States, securing donations of 1.24 million doses from Japan and 750,000 doses from the U.S. He emphasizes that the geopolitical context for Taiwan has changed over the last 10 years, with officials in both the U.S. and Japan more attentive to their relationship with Taiwan. This was demonstrated by Taiwan’s disproportionately large share of the 25 million vaccine doses the Biden administration recently donated to Asia.

Wang, the city council member, also believes that buying vaccines from China should not be the government’s first option, even though it shouldn’t be taken off the table in case the pandemic worsens. As for Chen, the Legislative Yuan member, he leaves the question of whether to buy Chinese vaccines to the epidemic command center.

“It’s hard for me to imagine” the Tsai government buying Chinese vaccines, says Templeman, the researcher. He believes that this issue demonstrates how partisan Taiwanese politics have become. “Everyone is seeing this issue through their own lens,” with each side seeing this issue according to the prevailing narrative in their respective camp. For pan-blue partisans, this means an abject failure by the government. For the pan-green side, that means smearing any criticism of the government as pro-China subversion.

Though Taiwan has a set of referendums planned for late August, Templeman believes that the low participation threshold required means that the political ramifications of the vaccine issue will only become clear after next year’s local government elections. “Taiwanese local elections are becoming more nationalized,” he says, meaning that they are increasingly becoming an opportunity for voters to rebuke the party in power. What this could mean for the cross-strait relationship and the development of the U.S.-Taiwan relationship is yet to be seen.