Chicken parenting is China’s helicopter parenting on steroids

Helicopter parents of America may be intense, but their counterpart in China — known as "chicken parents," named after a traditional Chinese medicine remedy involving the injection of chicken blood — can be just as over-the-top.

In the U.S., the concept of “helicopter parenting” became enough of a phenomenon that it was added to the Merriam-Webster dictionary in 2011 (the same year as “tweet” and “crowdsourcing”), defined as “a parent who is overly involved in the life of his or her child.” It was an about-face from the previous generation, when the conversation around parenting involved “latchkey kids,” i.e., children who returned to empty homes because their parents were so often away at work.

An oft-cited 2019 study by a Cornell researcher, Patrick Ishizuka, reports that a new American child-rearing philosophy is turning helicoptering to the next level. It’s a level that China knows well. Because over there, so-called “chicken parents” have been using a similar kind of intensive parenting, but on steroids — or in their case, on “chicken blood.”

In recent years, the term “chicken baby” (鸡娃 jīwá) has become popular in China, with the increase of obsessive middle-class Chinese parents in megacities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. “Chicken” comes from the colloquial expression dǎjīxuè 打鸡血, which translates literally to “inject chicken blood.” Chicken blood treatment was a fad during the Cultural Revolution, mostly in the countryside. People waited in line, rooster in hand, to receive fresh chicken blood — the cure-all for countless ills, from baldness to infertility to cancer. It was allegedly a great victory for the people, not so much for young roosters. Once the golden age for health gurus passed, the madness over chicken blood subsided — but the phrase survived as an expression to refer to agitation or hyperactivity.

“Kids in the past had extracurriculars as well, but it didn’t serve any purpose except to cultivate hobbies or fun,” said Lansing Jia, a high school teacher in Shanghai. “Today, chicken babies play chess to improve cognitive skills, participate in Math Olympiad for logical reasoning, sports to prevent myopia…Everything has to serve one purpose: to be good at school.”

After school, more school

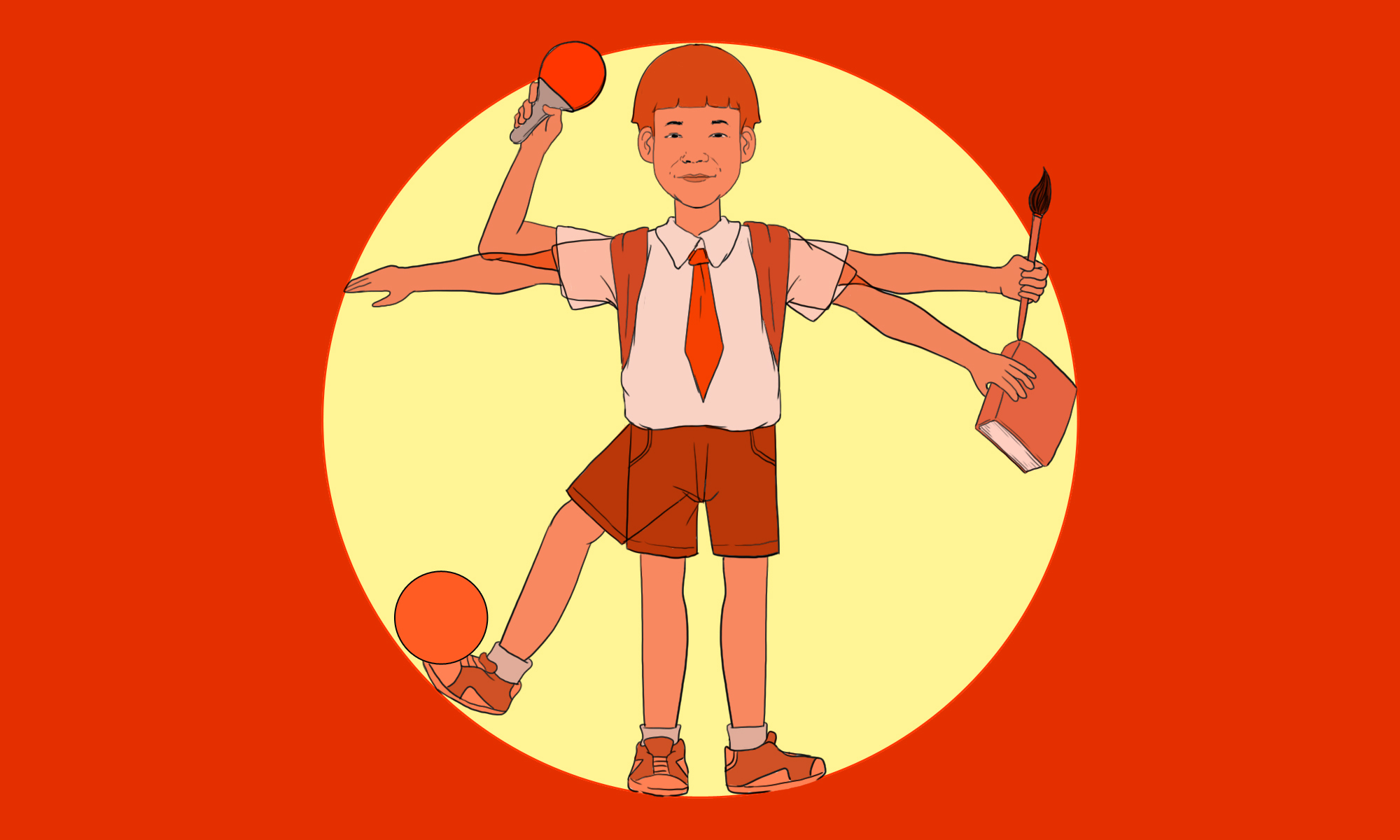

It’s not just schools that keep students busy. Good grades aren’t enough anymore, since there are too many children who are good at exams. Due to recent education reform in China, a student’s physique, cultural and artistic skills, as well as international experiences are also taken into account in school admissions.

Chicken parents in China send their children to local cram schools, training institutions where students can get extra help in English, math, Chinese, or other subjects. Like their American fellows, chicken babies in China also take sports, music, culture, or other interest classes, or volunteer in the community, since these can count as bonus points in the school entrance exams.

One mother shared a typical Saturday schedule of her son, who is in fifth grade:

8:30-9:50 a.m.: Reading

9:50-10:30: Gaming (for socializing with peers)

10:30: Eye exercise

11:00: Lunch while listening to audiobooks

1:00-4:00 p.m.: Math Olympiad practice

4:00-5:30: biking outdoors

5:30: Dinner

5:50-8:30: English lessons online

8:30-9:00: Snack break

9:00-10:00: Homework

10:00: Bedtime

“Extracurricular activities are just the norm,” said Hannah Chen, a parent whose daughter, a fourth grader in Shanghai, was voted class president, plays in the school orchestra, and takes piano, martial arts, Chinese, and math classes on the side. “How many extracurriculars children have, and how much time and money parents are willing to spend on it…that is what makes the real difference here.”

While “chicken parenting” might be a neologism, the educational rat race behind it has a long history in China. The Chinese government has long sought to curb the excesses of this rat race, but to little avail. Since the mid-1990s, the central government has allowed increases in the total number of university students as a whole. Last year, China adopted a lottery admission system for children during its compulsory education period spanning primary and middle school. This year, China’s Ministry of Education (MOE) has set limits on the amount of homework that can be given to young students. And most recently, a dedicated department was created to regulate China’s $120 billion after-school tutoring sector.

While these policies are aimed at “easing the burden on schoolchildren,” many parents reacted with resistance. Those who are especially unhappy are parents who purchased xuéqūfáng 学区房, literally meaning “school district houses,” as the MOE formerly dictated that public schools could only enroll pupils from designated areas.

The government may demand a more equal distribution of resources, but the reality looks rather different. Schools in urban areas are still divided into those for the elite and those for everyone else. And to get into one of these elite schools means students need to start studying at a very early age. “Many people don’t realize that if you don’t go to a good (middle or high) school, you have basically said goodbye to Tsinghua and Peking University (designated as elite universities in China),” said one mother whose son is enrolled in one of the six leading public schools in Haidian. According to statistics from Beijing Education Examinations Authority, more than 50% of high schoolers from Beijing who are admitted by Tsinghua and Peking University are from Haidian, one of the 16 districts of Beijing.

A vicious cycle

The drawbacks for children are obvious. China’s childhood myopia rate is among the highest in the world. The National Health Commission found that 71% of middle schoolers and 81% of high schoolers in China are nearsighted, causing a new hype over orthokeratology lenses — “OK lenses,” as Chinese parents call them — that are specially designed to be worn overnight, temporarily improving vision during the day. They cost between $1,000 to $4,000, and are popular among chicken parents. “Outdoor play can help prevent myopia as well. But OK lenses come quite in handy since there is little time left for (my child) to play,” the parent Chen explained to me.

Depression among Chinese teenagers is also increasing. The 2019-20 National Mental Health Development Report (in Chinese) found that 25% of Chinese adolescents suffered from depression and 7.4% of them had severe depression. By comparison, 13% of U.S. adolescents aged 12 to 17 had experienced at least one major depressive episode, according to the 2017 National Survey. Cuī Yǒnghuá 崔永华, director of Department of Psychiatry at Beijing Children’s Hospital, told China National Radio that much of the pressure that children are feeling comes from their parents.

More importantly, children are not given the opportunity to become individuals. They can develop a sense of entitlement and become anxious when left on their own. Some observers view chicken parenting as just another example of involution (内卷 nèi juǎn), a term describing intense competition in China, and argue that parents should protect children from this relentless competition instead of living their unfulfilled dreams through them.

A former “chicken baby” shared her experience with us: She felt worthless and hopeless for years just because she didn’t get exceptional marks at school. “Just like my peers, I tore up my textbooks after gaokao, celebrating my freedom after so many miserable years,” she said. “Even my mom went home in the middle of the night, drunk as hell. Except school, we both had no life at all.”

But as easy as it may be to criticize chicken parenting, people often forget how challenging parenting can be. Chicken parents keep themselves informed by staying active in WeChat groups that focus on school admissions; they help their child get into extracurricular activities that are often sold out very quickly; they attend tutoring classes to make sure they can home-tutor their child; they play and read with their child while managing a full-time job. Cornell researcher Patrick Ishizuka’s study also suggested that intensive parenting takes a toll on parents’ mental well-being, especially mothers who still bear the brunt of childcare-related work.

While looking for people to interview for this story, several parents who were suggested to me insisted that they weren’t “real” chicken parents, since there were many others out there who were worse than they were. One parent allegedly tried to bribe her daughter into a prestigious elementary school for $2,500. Stories like that abound.

“The sad part is that once you start chickening your children, it’s hardly possible to stop,” explained high school teacher Lansing Jia.

“Education shouldn’t be about having good scores and childhood shouldn’t be about overcommitted school schedules,” said Chang Xuemei, a kindergarten teacher in Shanghai. But the competition is too intense, and the stakes are too high.

Economist Matthias Doepke, co-author of the book Love, Money and Parenting: How Economics Explains the Way We Raise Our Kids, explained that in a society of very high inequality, parents will assume a parenting style that is more intense and more success-oriented. That seems to be the case in the U.S. as well as in China. But Chinese households are under much more pressure to work hard in order to not fall out of an expanding middle class.

A trending Chinese TV show that details the grueling middle school admission wars, A Love for Dilemma (小舍得 xiǎo shě dé), has sparked a broad public discussion on chicken parenting in China. A dad in this show speaks of a “theater effect” in this relentless competition: “One person suddenly stands up in a theater, and then others will stand up as well so they can see the show. In the end, everyone is standing, when they could have all just sat to watch.”