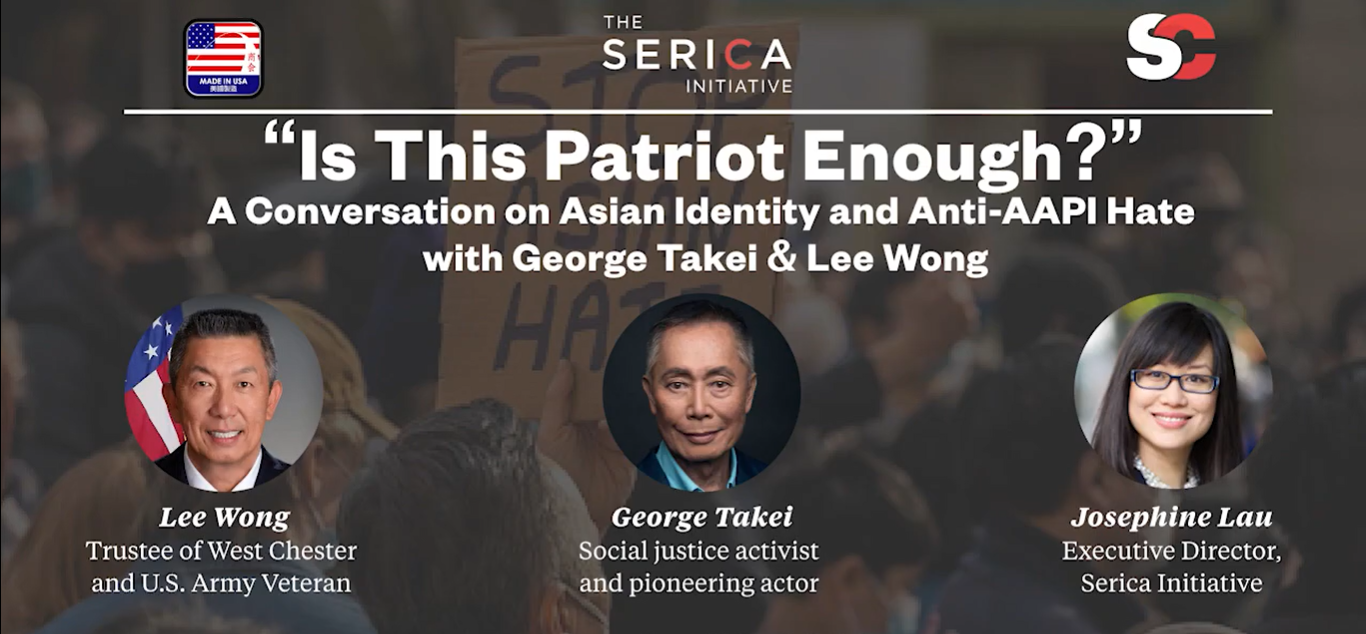

“Is This Patriot Enough?” A Conversation on Anti-AAPI Hate with George Takei & Lee Wong

“Enduring resilience is not just suffering with strength and pride; it’s also creating our own joy and happiness,” says George Takei, social justice activist and pioneering actor.

We’re providing highlights from a panel discussion on April 9th about Asian identity, anti-AAPI hate, and the next steps forward. Our panelists included George Takei, social justice activist and pioneering actor; Lee Wong, Trustee of West Chester and U.S. Army Veteran; and Justin Lock, Special Assistant for AAPI Issues with the U.S. Department of Justice Community Relations Service. This discussion was moderated by Josephine Lau, Executive Director of The Serica Initiative, and Kaiser Kuo, Editor-at-Large of The China Project and Host of The Sinica Podcast. You can watch the full discussion here. (Interview has been edited for clarity and length).

Serica: Asian-Americans have long been lumped as the eternal foreigner, as never being “American” enough. These notions have come to the fore in the recent waves of anti-AAPI hate. Lee, your gesture at a Town Hall meeting in Ohio in March reverberated across the nation. It was a really powerful image for you to show your scars from your time serving in the U.S. Army and ask the question “Is this patriot enough?” What inspired you to make that gesture and what do you think it will take for Asian Americans to finally be considered American or patriotic enough?

Lee: For too long, Asian Americans have experienced discrimination. This country was founded on hatred and discrimination. Even though so many Asian Americans have died for this country’s freedom and democracy, we still get treated as second-class citizens because of the way we look. So what should an American look like? It takes all kinds of people, faces, sizes, colors, countries of origin. Just as every religion has those who do not live up to the ideals of their faith, so too does the word patriot not hold up for those Americans who adopt a view that is narrow, exclusive, and hateful. Patriotism is a natural sense of pride in our nation’s accomplishments and identity. Patriotism that embraces the idea of the moral and political dimensions of being an American is a good thing for every American. To me, the greatest sacrifice a person can make is to serve in the military. We gave so much to defend and build this country, and we should be as proud as any other Americans. I couldn’t allow anyone else to come up to tell me that I’m not American enough.

Serica: George, you starred in a Broadway show called Allegiance, which wrestles with the issue of Japanese internment. The story was inspired by your own experience and one of the central themes of the musical was the concept of patriotism and loyalty. Many Asian Americans, and especially Chinese Americans, feel like they’re under loyalty oath pressure again, to double-down on their outward allegiance to America in this time of escalating tensions. What are the lessons that you think Asian Americans should learn from the experience of the Japanese American internment in the Second World War and the experience of having loyalty oaths administered?

George: Allegiance examines the word allegiance on three levels: to government, to family, and ultimately, to yourself. The offensive thing about loyalty questionnaires is the presumption on the part of the American government that we had an inborn loyalty to Japan. My parents were no-nos; they refused to bear arms to defend the nation that was imprisoning them and their children. And for that, they were categorized as disloyal, and transferred from an internment camp in Arkansas to the Tule Lake Segregation Center in Northern California. But then, there was a second group, a heroic group of young men, who said, “I will fight for my country as an American, but I will not go as an internee. I will not leave my family in imprisonment and put on the same uniform as the sentries guarding over my family.” This was a truly gutsy position. Taking that position, they were tried for draft evasion and found guilty, and transferred from an internment camp to Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary, where they were insulted, attacked, and spat on. They had to fight as hard if not harder than any other soldiers. I consider them just as heroic and courageous as those who went on to fight on the European battlefields.

Serica: Speaking of loyalty and service, Lee, you served in the U.S. Army for 20 years. Risking your life for your country is a pretty high standard for a demonstration of loyalty, and not something that most people can pull off. Do you believe though, that Asian Americans should have any obligation at all to demonstrate allegiance? Should there be any greater expectations for Asian Americans than for any other Americans?

Lee: We’re already at a disadvantage as Asian Americans because of the way we look. But I learned that getting involved in the government and to participate and run for office is the most important thing. You have a voice at the grassroots level, and it shows that we are capable of serving the country in different ways. Asian Americans have contributed greatly to the success of this country: from the Continental Railroad to the invention of fiber optics. And yet, Asian Americans still suffer from mistreatment, especially in the military. I felt a need to speak up because, if not, bad things would continue to happen for another 50 years. There aren’t a lot of Asian people in my township, but I’d still like to see more Asian faces represented in local politics.

Serica: George, you lived through the 1980s, when there was a surge of anti-Asian hate crime as well, much of it caused by the misperception that Japan was taking American jobs. But even the murder of Vincent Chin seems to pale in comparison to what we’ve seen here in the last year. What do you attribute to these spikes in anti-Asian hate? Was it just Trump and his rhetoric, or was there something more to it? And what can we learn from looking back at the history of the 1980s?

George: The history of immigration in this country is founded on discrimination against people coming from Asia. Immigrants coming from other parts of the world could someday aspire to become naturalized citizens, but Asians were denied that. There is a systematic prejudice that becomes law against us. Systematic discrimination is intrinisic to the mentality of the United States and it affects not only our community but the Black community and many others. Americans are diverse, and we don’t have to feel inferior because of the way we look, and we’ve got to educate the rest of America that our diversity is a strength of this country.

Serica: Justin, the value of diversity needs to be protected by law and policy. There’s been a raging debate, especially since the Atlanta shootings, on what constitutes a hate crime in anti-Asian violence. A number of experts say that it can be hard to prove a racist motive and attacks against Asians because there are no widely recognized anti-Asian symbols, something comparable to a swastika or a noose. How is the DOJ’s thinking unfolding on this, especially as anti-Asian violence continues to rise?

Justin: The first is that reporting is important. From the government’s perspective, in the absence of data, it’s hard to make decisions. We have to find ways to encourage reporting, to overcome obstacles of trust between communities and government, whether that be related to language accessibility, cultural competency, past experience, fear of discriminaton, or internal cultural stigma. The second is relationships. Having a relationship with local government or other communities of color can improve reporting as well as influence policy change. The final one is resilience. There are specific things that communities can do to improve and augment the ability of a community to respond to incidents of bias and hate, and also to prevent and dissuade potential future incidents. Across government, there are different tools that can be brought to bear. We can sit down and share with you more information on some of those nuances of what constitutes a hate crime and pre-positioning some of those conversations before a tragic incident happens, but we need your help to report anything you’ve experienced by contacting your local law enforcement.

Serica: Lee, what do you think are the most important actions that Asian-Americans should take to up our civic participation and to become a more powerful political block in this country?

Lee: I would encourage young folks today to take jobs as police officers and civil servants instead of traditional careers as doctors and engineers. It also protects our Asian American community. AAPI have to take initiative to stop ourselves from being marginalized, like any other group in America who wants recognition and fair treatment. We are going to have to toot our own horn more, and we have lots to be proud of.

Serica: George, I want to ask you about growing our power as part of the Asian-American community. Especially in the context of so much recent anti-Asian hate, what do you most want to do with the power you wield and what do you think needs to happen for the AAPI community to have more capital and power in mainstream American culture?

George: My father always said that this is a participatory democracy and we have to get in there and participate. Through participating, we become visible. And sometimes when our democracy is lacking, we have to fill that vacancy by reminding them of what these words mean. My father said that we’ve got to be resilient–gaman. But gaman isn’t all just teeth-gritting endurance, it’s to live. Under the harsh conditions of the internment camps, we had to make our own joy and our own happiness. My father saw beauty in that barbed wire sentry tower environment. Enduring resilience is not just suffering with strength and pride; it’s also creating our own joy and happiness. One of the other things my father did was to encourage me to participate in our democracy, by taking me to volunteer for the Adelaide Stevenson for President campaign. He said that the bottom line of a participatory democracy is voting, but not just voting, but casting an informed vote. And then after that, you volunteer for the issue or the candidate that you think is worthy. And after that, you run to be delegates to the party conventions. You participate in a participatory democracy and ultimately you run for public office. I had a friend, Senator Danny Noah of Hawaii, who became a very powerful political leader. He was the second-longest serving Senator of the U.S. and he was third in line from the President. He was a powerful Asian American politician, but he didn’t just represent Asian Americans. He represented everyone. In order to build allies for us, we have to be allies as well. We needed allies for the redress movement when we got an apology and redress from the U.S. government. Now, the Japanese American Citizens League is a supporter and advocate for the African-American redress program. Just like we have to educate other Americans about the prejudice toward Asian Americans, we have to educate our fellow Asians on supporting issues that face other communities of color as well.

*

Want to learn more? The Serica Initiative’s China Philanthropy & Nonprofit Newsletter is a monthly deep-dive into the trends, major players, and regulatory environment for philanthropic and nonprofit activity between the U.S. and China. Subscribe to the newsletter here.