The fog of words: Kabul 2021, Beijing 1949

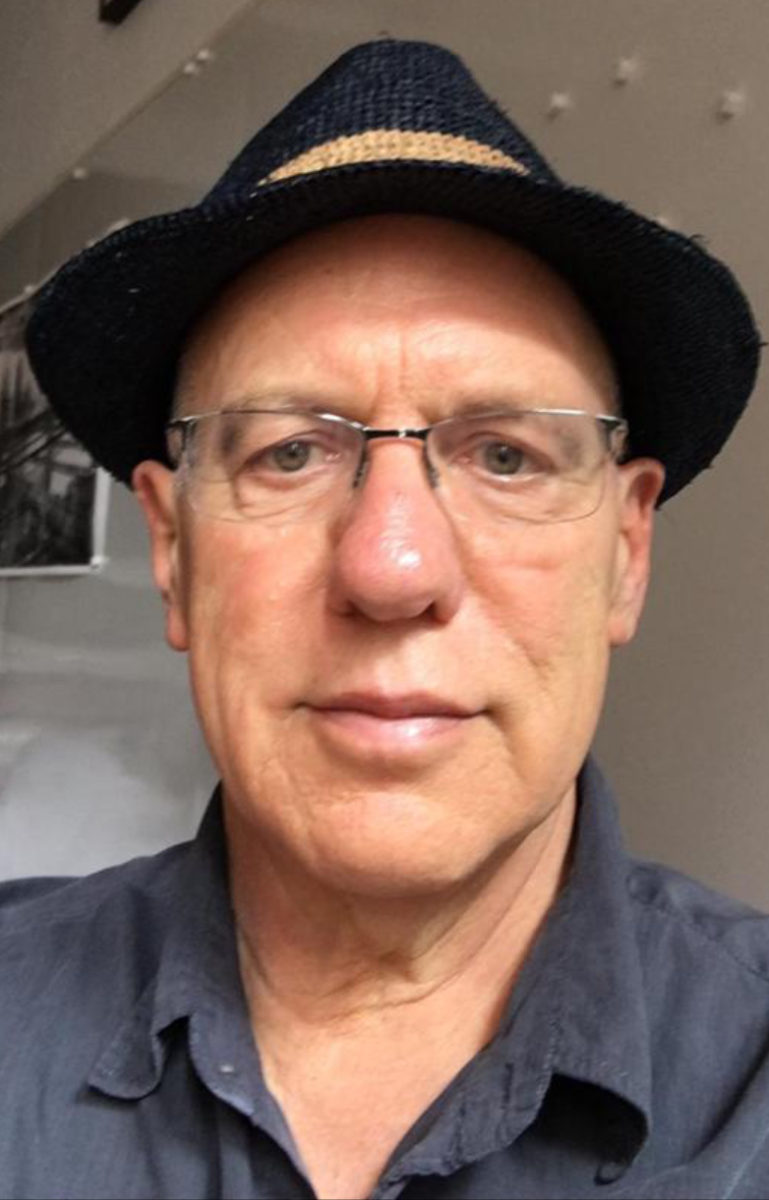

The fall of Kabul to the Taliban reminded some nationalistic Chinese commenters of the victory of the People’s Liberation Army in 1949. They have a point, argues the noted Sinologist Geremie R. Barmé.

Two steps back, one step forward

A battle-hardened insurgent peasant army equipped as much with a fanatical ideology as with weapons snagged from the enemy sweeps down on the capital after years in the wilderness, having been engaged in what seems like an endless civil war.

The victorious leaders talk about forming a coalition government that will embrace different political groups; they hold out the promise of moderate rule under which individual rights will be respected. They undertake to set up an administration that will usher in a new age in a war-torn land of a kind long denied by the previous corrupt and effete regime, one funded by the imperialist hegemon of the West. The incumbent government collapses dramatically and, as its leaders take flight, soldiers in what was a lavishly funded and state-of-the-art fighting force, now decisively routed, are assured by the incoming army that they will not exact revenge.

The commanders of the rebel force are inspired by an ideology that has hardened their hearts and narrowed their minds. They have secretly honed their fanaticism in mountain redoubts and caves over the years, believing above all that they represent not only the interests of all of their people, but the best hope for humankind. Their soteriology celebrates sacrifice and sanctifies the blood of martyrs; their aim is to strike fear into their opponents worldwide and advance a mission ordained by history itself.

The story of the Taliban’s blitzkrieg conquest of Afghanistan over the past 18 months brings to mind the history of a military force that conquered its domestic adversaries seventy-one years ago, the People’s Liberation Army of the Chinese Communist Party, which founded the People’s Republic of China in October 1949.

The analogy is not my concoction. In online China over the past two weeks, disparate members of a rowdy community featuring independent observers styling themselves as ‘Pinkies’ 粉紅 and derided by others as the ‘Maggot Masses’ 粉蛆 have celebrated the victory of the Taliban as the historical choice of the Afghan people. They have praised its army as a fraternal force akin to the PLA, one similarly dedicated to the interests of the broad masses of Afghans, a people long oppressed by a venal administration propped up by the American Imperium and its myrmidons.

Wáng Yìwéi 王义桅, a professor of international relations at People’s University in Beijing with a reputation as a ‘patriotic influencer’, already had form when it came to bloviating about the Taliban. In the lead up to the fall of Kabul, Wang had repeated a story on his Weibo page that the Taliban had been whetting their blades by reading On Protracted War, a famous series of lectures delivered by Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 in the wartime Communist cave enclave of Yan’an in 1938, adding that ‘it’s stunning to think that among the Taliban today studying Mao Zedong Thought takes precedence over reciting the Quran’ (Wang’s post, originally here, has since been deleted).

“The Taliban have been demonized by America but they are really Afghanistan’s ‘People’s Liberation Army,’” Wang subsequently opined on Weibo, “what’s more, they are true buddies of China” 塔利班是阿富汗的“解放军”,被美国妖魔化,却是中国的好哥们. In an onscreen analysis of the unfolding situation in Afghanistan posted on YouTube on 8 August, Wang went so far as to dub Taliban fighters “young revolutionaries” 青年革命者, comparing their push to conquer their homeland to the revolutionary efforts of the People’s Liberation Army during China’s civil war. Moreover, Wang offered, the American-backed regime in Kabul shared a lot in common with the corrupt Nationalist regime in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China that fell to the PLA on 23 April 1949.

Wang’s analogy was soon being amplified in China’s cacophonous maggot echo chamber. Although Wang later attempted to distance himself from his earlier comments, Sīmǎ Nán 司马南, a similarly opinionated and voluble nationalistic commentator, used his YouTube channel to argue that Wang had merely been ‘making a legitimate comparison’. Sima also essayed a lengthy cultural relativist argument about how the Taliban were all about championing the venerable traditions and unique national characteristics of Afghan society, including its attitude towards women. Other mainland commentators joined the fray (along with just about everybody else in the international commentariat) to dissect the precipitous withdrawal of the United States, its allies and the rout of the Afghan army.

In reality, China’s own pop analysts had a valid point when they talked about what they called an unmistakable ‘spiritual likeness’ 神似 shared by the Taliban and the People’s Liberation Army. This was particularly so in regard to the six fundamental policies of the Taliban in 2021: they are strikingly similar to the program of the PLA and the Communists in 1949. Contrast and compare: ‘Eliminate local warlords; rebuild the homeland; maintain strict military discipline; be fearless in combat; oppose corruption; and, develop the economy while encouraging commerce.’ (See a side-by-side comparison meme here, in Chinese.) Sima Nan returned to the topic of Mao’s ‘On Protracted War’ on August 22 when discussing the long-term conflict between China and the United States. Repeating what has in recent years once more become a theme in the fractious relationship between the two countries, Sima made a reference to the keynote slogan of the first national patriotic education movement launched as Chinese and American forces confronted each other on the Korean Peninsula in late 1950. The “Three Perspectives Education Campaign” 三视教育运动 employed a program of intensive indoctrination involving relentless study sessions, a media blitz, denunciations, self-criticisms, and thought remolding aimed at ridding people of ideas and sentiments that were deemed to be “pro-American 亲美 worshipful of America 崇美 and fearful of America 恐美.” The aim of the campaign was to free people’s minds so that they could “hate 仇视, despise 鄙视, and belittle 蔑视” the United States. (See the China Heritage series Drop Your Pants! The Party Wants to Patriotise You All Over Again.) The language of that campaign launched seventy years ago has featured once more during the U.S.-China trade war from mid 2019 (in Chinese) and ran as an undertone in Xí Jìnpíng’s 习近平 October 2020 speech (in Chinese) commemorating the seventieth anniversary of China’s involvement in the Korean War.

Whenever contemporary events inspire commentators in official China, not to mention their online surrogates and supporters, to draw historical parallels or make references to modern history, it is once more evident how effective the well-funded efforts of Party propagandists, educators, the media, and the arts have been since the early 1990s in generating an immersive environment for confounding issues, befuddlinging minds, and simply giving license to arrant nonsense.

As Yuán Téngfēi 袁腾飞, a Beijing-based independent historian cum story-teller, observed in a choleric outburst on YouTube (in Chinese) about Mainland commentators who had suggested that the Taliban (“a terrorist organisation gazetted by the United Nations”) and the People’s Liberation Army were somehow analogous: “It brings to mind a line in a cross-talk skit by Guō Dégāng 郭德纲: ‘I’ve got both good news and bad news. The bad news is that we’ve run out of food; the only thing left to eat is bullshit. The good news is that we’ve got lots of bulls.’”

In a society in which the “mirrors of history” only reflect a censored and funhouse distortion of the past, contemporary discussions invariably compound fiction with fervor. In the case of the current mainland comparisons between the Taliban in 2021 and the People’s Liberation Army in 1949, and the promise held out by those long-separated “military brothers of the people” 子弟兵, I would suggest, however, that there is more truth in the claims they’ve made than the likes of Wang Yiwei and Sima Nan might realize. So, my comparison starts at the point at which the PLA-Taliban analogy of today’s mewling maggots ends.

A treacherous heart

“Our experience proves that the Chinese people understand democracy and want it. It does not take long experience or education or ‘tutelage.’ The Chinese peasant is not stupid; he is shrewd, and like everyone else, concerned over his rights and interests. You can see the difference in our areas — the people are alive, interested, friendly. They have a human outlet. They are free from deadening repression.”

On 17 August 2021, the Taliban announced a general “amnesty” for patriots who had served as interpreters or in the military and in the civilian government. “We don’t want to take revenge on anyone,” declared Zabihullah Mujahid, the spokesman for the Taliban. “Nobody is going to knock on their door to inspect them.” At the news conference on Tuesday, the same Zabihullah Mujahid sought to assure residents of Kabul of “full security, for protection of their dignity and security and safety.”

“The Islamic Emirate doesn’t want women to be victims,” said Enamullah Samangani, a member of the Taliban’s cultural commission which, according to an Associated Press report, was ready to “provide women with an environment to work and study, and the presence of women in different (government) structures.”

However, as Omar Sadr, a political scientist at the American University of Afghanistan, told The Washington Post: “observing [the Taliban] from 1996 to now, they’re a hypocrite movement — hypocrite in the sense that their statements do not match their deeds and their actions.”

“The unity of words and deeds” 言行一致 is a much-used cliché favored by China’s Communist Party. From the 1940s, however, the Communists have been remarkable for the gaping chasms created between their promises and their actions.

From 1941, two years before the launching of the Yan’an Rectification Campaign that would impose — with an iron will and considerable (often deadly) violence — ideological unity on the core Communist forces at the wartime base, until August 1949, Mao and his comrades pursued a multifaceted and highly sophisticated strategy of public and private disinformation.

The efforts made by the Communist leadership to charm John Service were merely part of comprehensive hearts-and-minds effort aimed at convincing the Chinese public, in particular the intelligentsia, as well as the United States that the Communists would realize the aims of the original Republican revolution and establish a unified, strong state that was underpinned by a constitutional order protective of universal suffrage, human rights, a suite of civic freedoms, and respect for the dignity of all.

For eight years, in various media outlets, as well as in private exchanges, talks, interviews, and articles, the Communist Party’s propaganda industry and Party leaders dissembled, lied, dodged, deceived, and tergiversated. They were building trust on the basis of arrant false promises; they were generating the great falsehoods that did, and still do, form the marrow of the People’s Republic of China. They operated a factory of lies.

Readers interested in the fascinating, and excruciating-to-read, details of this conspiracy of disinformation are encouraged to consult History’s Herald — Solemn Undertakings Made Fifty Years Ago 历史的先声——半个世纪前的庄严承诺, an invaluable collection of official Party pronouncements compiled by the journalist Xiào Shǔ 笑蜀. Published on the eve of the fiftieth anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic in 1999, it was immediately banned.

In 2008, the investigative journalist and historian Dài Qíng 戴晴 offered an account of the complex background to the celebrated “peaceful liberation of Beiping” in 1948, some sixty years earlier. At the time, fellow travelers of the Communists as well as “third way” political activists and intellectuals who enjoyed considerable political and media influence were assured that they would have a substantive role in a new coalition government. The representatives of sympathetic political organizations would, according to Mao, offer oversight and act as a crucial check on the Communists; together, they would create an inclusive and democratic new country unburdened by the feudal and autocratic habits both of tradition and of the defunct Nationalist government of the old Republic of China. Within months, however, these high-profile “useful idiots” were one by one subjected to a harrowing process of ‘thought realignment’ and, over time, to various forms of persecution and imprisonment, leading, in some cases, to death.

Just as the consolidation of Mao’s domination of the Chinese Communist Party at Yan’an in the early 1940s had involved the remolding of the souls of Party members — a process that, when necessary, also entailed imprisonment, forced labour, and torture — so the founding of the Chinese People’s Republic involved the creation of a nationwide network of detention centers, prisons, and labour camps. In one of his first acts as the mayor of the newly “liberated” Beijing in 1949, PLA General Niè Róngzhēn 聂荣臻 (1899-1992) established the territorial “exclave” of Qinghe 清河, literally ‘clear river’. The 115 square kilometer zone of exurban desolation 150 km from the capital was a vast mosquito-infested marsh carved out of the territory of the municipality of Tianjin. Qinghe State Farm 清河农场 was then established to deal with the undesirables and social flotsam and jetsam of old Beijing. The name of the “reform through labour” farm was inspired by the Party’s insistence that those who were despatched to the bog would “have their souls cleansed by clear waters” 清清河水涤荡灵魂. Through forced labour they might even be deemed worthy of eventually taking up a role in the new society, or chóngxīn zuòrén 重新做人, as the clichéd expression of the Public Security Bureau that ran the exclave put it.

After all, the defeated bourgeoisie, represented by the Nationalist Party and a raft of pro-American sympathisers, along with various intellectuals, social parasites and misfits, malcontents, and recalcitrants, belonged to a dying world, one that was destined to disappear as China advanced along the path of historical progress. Why not, as Mao argued more than once, give them a helping hand on the way out?

A chronology of perfidy

Officially, in 1948-1949 American policy makers believed that, despite the Communist victory, “the democratic individualism of China will reassert itself;” although, for his part, Mao lambasted the selfsame elite “democratic personages” in which Washington expressed such confidence (see Mao, “Cast Away Illusions, Prepare for Struggle,” August 14 1949).

Previously, the prominent ‘democratic individualists’ and other key members of the media, business community, faith groups, and educational world had participated in a united front to help the Communists secure their military victory, now policy volte-faces came thick and fast. Henceforth, and regardless of whether the decades of twists and turns in the Party line are regarded as policy adjustments, re-alignments, or simply dialectical backflips, betrayal has continued to lurk in the dark heart of Chinese governance (See: Jianying Zha, China’s Heart of Darkness). Below I offer a brief outline of a few of the better-known examples of the Party’s perfidy, from 1949 to the mid 1950s:

1950: Promises to maintain social stability and only gradually transform the social fabric of the society were cast aside as a nationwide class classification system created a new hierarchy that, in combination with a quasi-legal process saw millions of undesirables executed (some 700,000 in 1950 alone) and Party cadres and enthusiasts come to enjoy both life-and-death powers and a secret system of privileged access to housing, foodstuffs, educational opportunities and a raft of other jealously guarded perks;

1950: A new cultural regime was imposed, based on the Yan’an and Soviet models and informed by Mao’s artistic vision, that rejected individual creativity and non-utilitarian arts. Purges of all cultural forms and works deemed to be “bourgeois” and an elaborate system of nitpicking and stifling invigilation would become the hallmark of official arts policy;

1950: The mass confiscation of “unhealthy” books from publishers, bookstores, and stalls was combined with a universal system of censorship of “thought, word, and deed;”

1951-1952: Having dismantled the court system and legal apparatus of the Republic of China, the Communists governed by decree and through mass mobilisation campaigns, a form of rule that was later regularized in a harsh system of quasi-military control. During the Three Anti and Five Anti campaigns, non-compliant officials and functionaries who had served in the previous government were eliminated, often physically, further cauterizing what remained of the country’s already depleted civil society, and the first anti-corruption campaign aimed at the Party itself was launched, used by many to settle scores and neutralize bureaucratic opponents. Without a functioning independent legal system or body of law, let alone any efficacious independent channels for redress, including via the media, Party law now held sway;

1950-1956: The media and publishing industries which had been promised an uncensored future were turned into propaganda organs and generations of writers, editors, and journalists had no choice but to adjust to the new reality. Those who did not comply were relegated to menial jobs or subjected to various forms of “re-education;”

1950: The occupation of Tibet under arms took place and a “Seventeen Point Agreement” was signed the following year. Beijing soon reneged on key aspects of the agreement leading to the Lhasa Uprising of 1959;

1952: The intelligentsia and students whose support had been crucial to the Communist cause against the Nationalist Party were subjected to the first of an ongoing process of “thought reform.” Many older academics and bureaucrats from the former regime, having failed to “pass the test” 過關 because their self-criticisms were found to be insincere or because they were denounced by their erstwhile colleagues, were stripped of their credentials. In a not inconsiderable number of cases the unreconstructed were purged from their jobs, committed suicide, or killed during frenzied struggle sessions;

1953: Mao and the Party had promised the country’s industrialists and business community that a mooted Soviet-style nationalization program would be delayed for years, if not decades. A “Shared Program” was to ensure the revitalization of the economy and safety for the investments of red capitalists and patriotic businesspeople. With Stalin’s death, however, the Chinese Party entered a phase of extreme competition with the Soviet Union as it vied to become the centre of global revolutionary change. This ideological shift led Mao, Liú Shàoqí 劉少奇, and their comrades to abandon the coalition strategy of “new democracy” in favor of increasingly radical policies the effects of which would stymie the economy until 1978;

1953: The Party’s ideological competition within the socialist bloc included an acceleration of efforts to nationalize land that had only recently been allocated to farmers, something that had been a key pillar of the policies of “the liberation.” This led first to the creation of rural cooperatives and, egged on by local Party militants who were backed up by Mao’s utopian enthusiasm, to communes, in the process depriving rural communities of local identity and hard-won dignity;

1953: A purge of intellectual life accompanied by a nationwide denunciation of liberal humanism and independent academic culture in the humanities and social sciences was launched in October of this year. Accompanied by the imposition of a strict Marxist-Leninist (that is, Stalinist) ideological framework in all spheres of education and research that crippled innovative and independent thought, scholarship was hamstrung for decades;

1954: A constitution, modeled on that of the Soviet Union, was rubber-stamped into existence by a supine legislative body. The numerous undertakings regarding rights and liberties made during the disinformation campaign of 1941-1949 were realized on paper only;

1956-1957: The Hundred Flowers Campaign that initially licensed the leaders of former political parties as well as intellectuals, students, writers, media professionals, cultural figures as well as workers to criticize the Party’s “work style” (that is, its autocratic ways) led to a large-scale purge when Mao realized that workers in key industrial cities were on the point of rebelling against the Party’s heavy handed and exploitative rule. In the following months, Deng Xiaoping, who was given oversight of the logistics of the purge, engineered the exile of over 500,000 men and women to distant locales and labor camps.

And that’s not to mention the promise of egalitarian wealth and communism from 1959 that led to the largest man-made famine in history…

For all of the achievements of the first decade of the People’s Republic in regard to public hygiene, gender equality, literacy and education, large-scale industrial and irrigation projects, as well as social quietude, the lawlessness of the Old Society was actually replaced by a draconian form of institutionalized brutality and a litany of double-dealing.

In 2021, nearly all of the people who knew firsthand of the promises that the Communist Party had made from 1941 to 1949, as well as those who had personally experienced the betrayals of the 1950s, are either extremely old or dead. For the most part, the leaders of Xi Jinping’s administration themselves are only familiar with a history long since red-washed into mythology. Although Xi enjoins the nation to think of “history as a mirror” that can help guide the future 以史为鉴, at best the image reflected back at the viewer is a grotesque distortion of a misremembered reality.

On June 9, 1989, Deng Xiaoping declared that, despite its economic policies, the Communist Party was engaged in a protracted war with liberal values and Western-style democracy. Under Xi Jinping that war continues on a number of fronts, including in the areas of history and education. Over the years, many have fallen in the struggle; I think, in particular, of leading independent-minded historians, thinkers and journalists like Zhāng Zhènglóng 张正隆, Dài Qíng 戴晴, Gāo Gāo 高皋, Yán Jiāqí 严家其, Líu Xiǎobō 刘晓波, Gāo Huá 高华, Yuán Wěishí 袁伟时, and Xǔ Zhāngrùn 许章润, to name but a few. Countless others have similarly been condemned to silence, their voices stifled or never even heard, their works languishing unpublished or censored out of existence. The real casualties, however, are the citizens of China who, as a result of the Party’s tireless war, are denied the right to know, to discuss openly and interrogate freely their history, to revisit the past from new angles and in new ways. The mind-boggling fog of words that is generated by this protracted war also frustrates those who seek to understand more than the confabulated official China Story.

With the past beyond independent investigation, consideration and debate, in China today history has one overriding function: to lionize the party-state, its sacred mission and its infallible leaders. And this is how contemporary Chinese commentators have found themselves so comfortably ensconced with the stated ideology and social goals professed by the Taliban in Afghanistan in August 2021.

An Earlier Ending

In late April 1975, I was visiting friends at Peking University shortly before my twenty-first birthday when news came through of the fall of Saigon. At PKU we saw our Vietnamese classmates, VietCong veterans who were all much older than us, celebrate the “liberation” of South Vietnam. The only American we knew was the daughter of a patriotic overseas Chinese capitalist and most people in my social crowd either had protested against the Vietnam War in their home countries, or had scant sympathy for America for other reasons. Nonetheless, even in those, my most Maoist-adjacent, days I knew enough about the Korean peninsula, the post-War fate of Japan, Berlin and the details of other countries that had staved off the convulsion therapy of Soviet-style state socialism to realize that Vietnam, long devastated by civil conflict, would now probably enter another harrowing phase of its history. Regardless of that gloomy prospect, along with many others I felt uplifted at the wild joy of our Vietnamese classmates; anyway, it was thrilling since it was in such stark contrast to the dour Chinese student body of former Red Guards, not to mention the phalanx of militantly humorless and besuited comrades from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

This is the first part of a two-part historical meditation and a chapter in China Heritage Annual 2021, the theme of which is “Specters & Souls — Vignettes, moments and meditations on China and America, 1861-2021.” Part Two is titled “The Restoration Era of Xi Jinping.”

— GRB, August 23, 2021

Related material:

- China’s Promise, January 20, 2010

- White Paper, Red Menace — Watching China Watching (VII), January 17, 2018