Idol worship and fan culture in China, explained

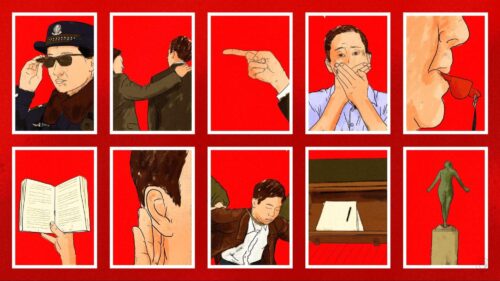

The fan economy drives a big part of China’s entertainment sector. But several recent high-profile cases of toxic fandom have caught the eye of the state’s internet watchdog.

The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), China’s internet watchdog, announced on August 27 that it would ban online lists that rank celebrities by popularity from all digital platforms. This announcement was just part of an ongoing two-month crackdown on online fan circles.

The campaign, called “Clear and Bright,” started in June, with the CAC saying in a statement that it would put an end to cyberbullying and rumor-spreading. Some of the behaviors being targeted include inducing minors to raise funds, vote rigging, and agitating fans to flaunt their wealth and extravagant lives.

The celebrity-ranking ban follows the CAC’s removal of 150,000 pieces of “harmful online content” and punishment of more than 4,000 accounts related to fan clubs, according to a recent Xinhua report.

How did we get here?

The campaign was originally launched after an incident in May that came to be known as the “milk waste” scandal. The popular talent show Youth With You 3 encouraged viewers to buy milk and scan the QR code inside the bottle caps to support their favorite stars on the show. Videos of people opening bottles of dairy products and dumping the contents into drains went viral. Some calculated that 270,000 bottles of dairy products were poured directly into the sewage. Intense online backlash caused the show to be suspended by the Beijing Municipal Radio and Television Bureau.

While it may be tempting to consider the Clear and Bright campaign as yet another one of China’s crackdowns on entertainment and pop culture, there are some differences between this campaign and previous ones aimed at, say, hair color.

For one, the fan economy in China is driven mostly by minors. An average online fan club has millions of young (mostly female) followers ready to support their idols by contributing money or actively buying the idol’s advertised products. Often, they go beyond spending money. For example, fans can raise an idol’s commercial rating and help him or her get even more endorsement deals if they took a screenshot of the purchase, tagged it with both their own username and the brand’s social account, and uploaded it to social media.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

Cooperation with Chinese idols is a proven method for brands to grow their reputation. In 2019, Estee Lauder announced Xiāo Zhàn 肖战 (Sean Xiao), a popular Chinese singer and actor, as its brand ambassador just before Singles’ Day, the world’s largest online shopping festival, held on November 11 every year. As a result, sales exceeded 40 million yuan ($6.2 million) in one hour. U.S. cosmetic brand Origins reported similar results. Its collection, made in collaboration with Wáng Yībó 王一博, surpassed 30 million yuan ($4.6 million) in one hour. Last year, Chinese actor, singer, and dancer Jackson Yee (易烊千玺 Yì Yángqiānxǐ) became a global makeup and skin care ambassador for Armani Beauty and an Emporio Armani global ambassador.

In the early 2000s, the rise of social networks fundamentally changed the face of fandom, turning it from a pleasant communal activity into something competitive, chaotic, and even abusive.

According to the “White paper on idol industry and fan economy in 2019,” China’s idol market was expected to reach 100 billion RMB ($15 billion) by 2020, with a year-on-year growth of around 60%. President of Professional Content Business Group (PCG) and Chief Content Officer of iQIYI Wang Xiaohui once estimated that the idol market in China will be valued at about 140 billion yuan ($21.6 billion) in 2022.

Some studies show that of the estimated 500 million “idol chasers” (defined as anyone ready to spend money on an idol) in China, 36% are willing to spend 100 to 500 RMB ($15 to $75) per month. What do they get in return? Emotional satisfaction, an academic analysis of the fan economy says, like having a good conversation with a friend. This feeling is the key element of the so-called “emotional capital” (情感资本 qínggǎn zīběn) of the star. The more people feel that a celebrity can understand and satisfy their emotional needs, the more emotional capital they get.

Fandom culture is not new. Long before the internet, fan clubs were organizing gatherings, publishing magazines, and writing fan fiction. But in the early 2000s, the rise of social networks fundamentally changed the face of fandom, turning it from a pleasant communal activity into something competitive, chaotic, and even abusive.

In China, the main driving force behind this evolution of fandom is Sina Weibo, the largest social media platform in the country. In addition to helping enthusiasts find their communities, Weibo also brought celebrities and their supporters closer together by breaking down the wall between them. According to Yin Yiyi, an associate professor of media and cultural studies at Beijing Normal University, in 2011 Weibo invited celebrities or institutions in different areas to join the platform and interact with their followers. In 2019, the most popular idol singers could have more than 20 million followers on Weibo. Now we also call these followers fěnsī 粉丝.

At its core, the way Weibo operates in the world of fandom is no different than its global counterparts like Twitter and Instagram. But if in the West the relationship between stars and their fans can be called one-sided — fans just follow, consume content, or copy the lavish lifestyles on display — in China the relationship is more co-dependent. And that’s where the CAC believes it needs to step in.

Petty fights between fan communities can lead to huge financial losses for the brand and hurt the artist’s career.

On one hand, as artists have come to recognize their direct influence over swaths of their diehard fans, they have also come to rely on their constant consumption. In 2020, Seoul National University’s Consumer Trend Center professor Kim Rando introduced this kind of fans (or fensi) as “fansumers” in his book Trend 2020. The word “fansumer” is a portmanteau of “fan” and “consumer,” highlighting the fact that fans not only follow their favorite celebrities and purchase the products they advertise, but are also engaged in idols’ marketing campaigns and even in the overall production process.

“Consumers now have a desire to personally participate and invest in the manufacturing process of developing products, brands, and stars. This new type of consumer who takes part in the entire life cycle of a product and exercising their control over it is termed a ‘fansumer,’” Kim writes in the book. “They actively support and purchase a product with the pride of having raised it personally. The fansumer’s influence is continuously expanding, and it includes participating in crowd-funding, engaging in supporter activities, rooting for or criticizing celebrities and influencers, and many more.”

On the other hand, sometimes petty fights between fan communities can lead to huge financial losses for the brand and hurt the artist’s career.

Last year, an incident involving Xiao Zhan and Wang Yibo is still resonating today. In January 2020, two big fiction publishing platforms published a story about the two idols falling in love with each other. Xiao’s fans, who were very unhappy about having their favorite idol’s identity used in homoerotic literature and started the aggressive campaign against the authors, successfully lobbied to get these two publishing platforms taken down. This was then met with angry protests from China’s LGBTQ community. Millions of activists began boycotting Xiao Zhan and the brands he campaigned for, including Estée Lauder, Piaget, and Qeelin. Moreover, they began promoting the competitors of the brands Xiao had been affiliated with and crashed Xiao-sponsored brands’ customer service lines, pressuring them to end their collaborations with Xiao.

“Xiao Zhan’s fans have harassed others so violently online that they managed to kill a source of creativity and expression for a massive number of people,” a Beijing-based PR professional told Jing Daily. “This is an example of modern-day toxic fandom in China.”

Perhaps even worse example of disturbing fan behavior happened after Chinese-Canadian pop idol Kris Wu (吴亦凡 Wú Yìfán) was arrested by Beijing police for suspected rape. One month before the arrest, several women came forward to allege they were drugged and raped by the star. After the pop idol was detained, more than 24 women, some of them underage, opened up with similar stories. But Wu’s fans defended him online, even blaming the victims. Some fans even suggested going to jail to rescue their beloved idol. These sorts of comments resulted in the closure of hundreds of Wu’s online fan communities.

The CAC’s crackdown reflects the power of social media platforms. With the help of fan circles, they easily influence online public opinion. The potential of idols to sway public opinion and mobilize groups creates a level of danger that the Chinese government can no longer abide.

Acting “in the public interest,” especially when it comes to such a sensitive issue as sexual harassment and assault, the government’s recent action has garnered lots of positive responses. The revolting action of Wu’s fans has only added to the fuel, and allowed some to view the CAC’s Clear and Bright campaign as a noble fight, rather than censorship.