The rise and fall of Shanghai’s ‘coffee king’

Chang Pao Cun was a coffee pioneer in China, one of the first people to bring the dark caffeinated beverage to locals. But his story, set against the unhinged origins of Shanghai coffee culture, is also full of tragedy.

This article, published with permission, is an abridged version of a study of coffee history in Shanghai, conducted by the Little Museum Of Foreign Brand Advertising in the R.O.C., which you can read in full here.

In March, a research firm based out of Shanghai claimed that Shanghai has the most coffee shops in the world. The study only looked at three other major international cities — Tokyo, London, and New York — but the results were nonetheless startling: Shanghai has nearly 7,000 dedicated coffee shops, while Tokyo has 3,826, London 3,233, and New York 1,591.

This news may come as a surprise to coffee connoisseurs outside of China, but Shanghai in fact has more than 150 years of history in roasting, brewing, and serving coffee.

In précis:

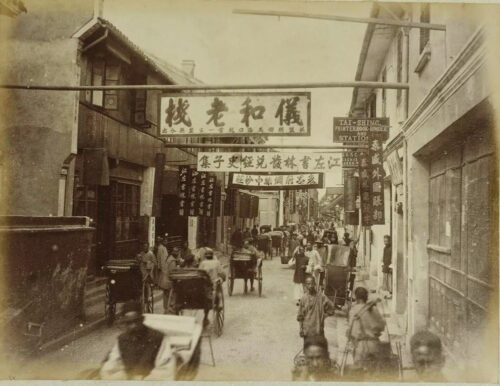

After the creation of the Shanghai foreign settlements in 1843, the earliest venues to offer coffee to its Western residents and travelers were hotels. A rather curious first attempt to introduce coffee to Chinese consumers was reportedly made by the Llewellyn & Co. Drugstore: British Pharmacist J. Lewellyn sold coffee to local Chinese as “cough potion.” While the medical benefits didn’t seem to have convinced its customers, the venue turned to regularly selling coffee and pastries in addition to drugs, which is why it later became known as the Llewellyn Western Restaurant.

In 1886, the Temperance Society of Shanghai, worried about foreign sailors spending “too much time drinking and visiting loose women,” proposed to pool funds to organize a coffee house, which became the Hongkew Coffee House and Reading Room — probably Shanghai’s first real standalone cafe. It served “coffee, tea and non-intoxicating liquors,” according to an article published in The North-China Herald on January 13, 1886, to draw sailors away from those “horrible dens where instead of being comforted with whole-some liquor they are poisoned with vitriol, and petroleum, and all the other ingredients of adulteration.”

In 1897, the oldest Shanghai restaurant still active today, Cosmopolitan Butchery, was founded in Hongkou (then spelled Hongkew). After the First World War, it changed to Chinese ownership and remains open today as Deda Western Restaurant.

In 1924, the first mass production facility for coffee in Shanghai was founded under the name Shanghai & Hongkew Wharf Yuji Coffee Company. In 1928, the New Kiessling Cafe became the talk of the town as the first Chinese-run Western-style coffee house in Shanghai. It was founded by the foreman of the German Kiessling and Bader Restaurant in Tianjin along with two other Shanghainese pastry chefs. Initial funding was allegedly provided by northern warlord “Commander K,” after whom the venue’s Chinese name was created. Legend has it the warlord later sued for name infringement but lost. Eileen Chang immortalized this cafe in her novella Lust, Caution, when a character recalls a famous cheesecake. The cafe still exists today at the very same location on 1001 Nanjing West Road, making it the longest-standing coffeehouse of Shanghai.

In 1928, an article in Shenbao News introduced readers to a cafe called Shanghai Café on North Sichuan Road in Hongkou and frequented by many Chinese celebrities of art and literary circles, including Lǔ Xùn 鲁迅, Yù Dáfū 郁达夫, Gōng Bīnglú 龔冰廬, Meng Chao, and Yè Língfèng 叶灵凤. Lu Xun also frequented Gongfei, a cafe near his residence that would go on to become the cradle of the leftist cultural movement. Lu Xun’s coffee hangouts continue to exist today as the Old Film Café on Duolun Road (formerly Darroch Road).

A third wave of coffeeshops followed in the late 1930s, started by Jewish refugees — most notably from Vienna, one of the best coffee towns in the world — who brought their distinct coffeehouse culture and traditional names such as Fiaker, Kolibri Café, Café Elite, Zum Weissen Rössl, and Wiener Stueberl (famous for its Viennese apple strudel).

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

But in all this time, Shanghai coffee consumption was largely driven by foreign residents and a small Chinese intellectual elite. That would finally change in the 1930s, with the emergence of domestic entrepreneurs in the coffee market. One name in particular would rise like cream to the top of the Shanghai coffee world.

King of the Shanghai lao kele

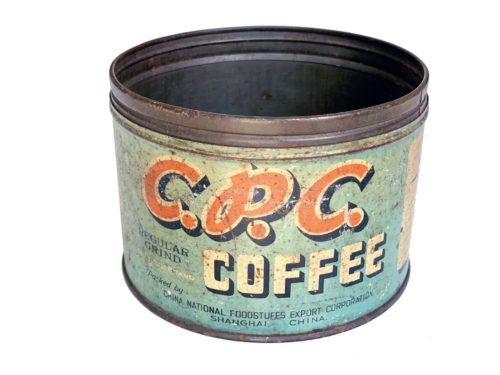

In 1935, Chang Pao Cun (张宝存 Zhāng Bǎocún), a Zhejiang native, founded Desheng Coffee (德胜咖啡行 dé shèng kāfēi xíng) with his wife on No. 22 Broadway. It was Shanghai’s first large-scale coffee roastery and distribution company under Chinese ownership. It imported raw coffee beans from abroad, roasted them, and sold them packaged in tin cans to Western restaurants and cafes under the registered trademark of “C.P.C.” (Chang’s initials, not to be confused with the “Communist Party of China”).

Japanese attacks in 1937 forced Chang’s company to move locations. He opened the C.P.C. Coffee House, a.k.a., Desheng Café, on 1472 Bubbling Well Road. What was then part of the International Settlement and close to Jing’an Temple is now the intersection of Nanjing West Road and Tongren Road, occupied by the United Plaza building.

This C.P.C. venue soon became one of the most famous coffeeshops in Shanghai, frequented by the so-called lao kele (老克勒 lǎo kè lēi) — white-collar Chinese workers who adopted a Western lifestyle. Drinking coffee became a symbol of nobility, status, and taste among the rising Chinese middle class.

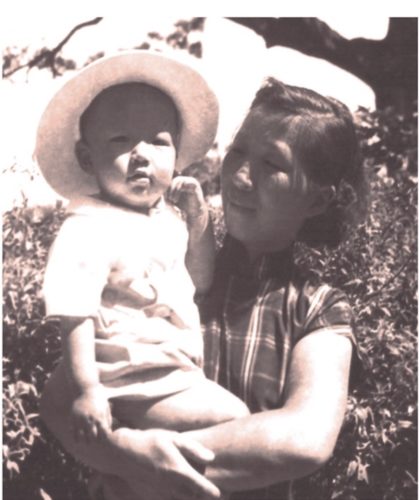

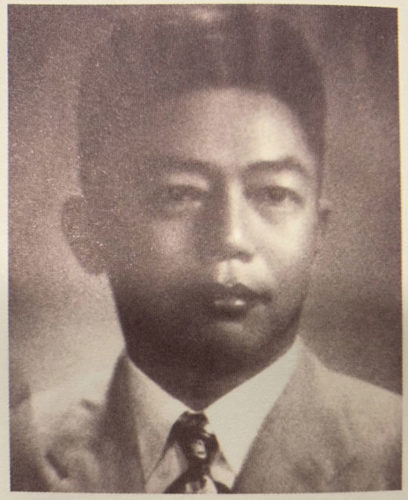

Chang himself was a prototypical lao kele, given his English-language education and early involvement with foreign businesses. He was born in 1913 close to Ningbo as the youngest son of the family. Family sources say both his parents died when he was seven. He was sent to Shanghai at age 14 to enroll in the English-language St. Francis Xavier’s College. At 16, he got his first job working for the foreign-managed Powers Co., Ltd., whose main business was in coffee and fruit trading. These apprenticeship years undoubtedly laid the groundwork for his later success. When he turned 18, Chang moved to Hong Kong. When he returned to Shanghai two years later, he founded his first business, the Honolulu Food Company. The January 28 incident forced him to close his company in 1932.

In 1934, Chang married Fāng Huìqín 方慧琴. Born 1917 in Zhenhai, Zhejiang to a poor rural family, Huiqin moved to Shanghai at the age of eight. She met Chang while working at a small vegetable market on Seymour Road (now Shaanxi North Road). The couple established Desheng Coffee together. Fang was involved in the business from the get-go, personally roasting the coffee beans, controlling the temperature, and selecting recipes.

After successfully operating their family business for several years, Chang became recognized as the originator of the domestic Shanghai coffee industry and served as the representative of the Shanghai Coffee Association for 10 straight years. Chinese newspapers of the time referred to him as the “coffee king” and claimed “7 out of 10 Shanghai coffee shops use CPC Coffee.” (The title “coffee king” was shortly contested in the English-language press by S.H. Levy, owner of Levy’s Coffee, until he vanished to Palestine after the chaos of the Japanese occupation.)

In December 1944, Chang opened a second C.P.C. coffeeshop, this time in the former French Concession, on No. 534 Taishan Road (today’s Huaihai Road). The building which housed the cafe still exists today, and is right across the street from a hipster coffee shop ironically called No Coffee.

After the boom of the 1920s and 1930s, there was a depression during the war with Japan, which caused shortages and rising prices in imported coffee beans and international brands such as the American S & W Coffee (which briefly maintained a failed coffeeshop on 889 North Sichuan Road). Chang spun the situation to his advantage, as he allegedly engaged in price fixing, unpaid import invoices, company re-incorporations, and other shenanigans.

Nonetheless, shortly after the war, urban coffee culture enjoyed a big revival, and by 1946 there were 186 cafes registered in Shanghai and altogether more than 500 venues serving coffee. Among them, Cafe Louis & Confectionary, Seventh Heaven Café, Maxwell House Café, New Dollar Café, Renaissance Café, Swan Café, Lady Bird Café, Carnation Café, Café Roy, Café Rex, Corso Café, Foch Café, and the Vienna Café.

By 1949, Desheng was flourishing, and extended its distribution business to Hong Kong, with plans to open a branch in Kowloon. Desheng also managed a third Shanghai location in the former French Concession on Rue Lafayette: the shop reportedly had been opened by 1930s movie star Hán Lán’gēn 韩兰根, who mismanaged it and asked his friend Chang to take over.

Things were going so well that Chang also opened the Chinese United Bakery factory, producing breads, candies, mooncakes, chocolates, canned coffee, and canned food, as well as the Chinese United Chemicals factory, which manufactured synthesized DDT as insecticide. He was also praised by the Chinese press for his charity work: A Shunpao article from August 24, 1944 mentions “hundreds of thousands of yuan” in donations to two primary schools in his hometown of Dinghai. Wisely, he supported student aid activities organized by Shanghai’s two major newspapers, Shunpao and Xinwenbao, which further helped raise his and C.P.C.’s public profile.

C.P.C.’s brand awareness was so high that in 1945, a knock-off brand called C.Y.J. emerged selling “coffee cigarettes.” Imitation is the highest form of flattery, as they say. But when it came to real coffee, C.P.C. dominated, leaving smaller three-letter acronym competitors such as A.B.C. Coffee and the Brazilian E.B.C. Coffee Company in the proverbial dust. It was also during this time that Chang reportedly bought the first Cadillac sedan in Shanghai, which was imported from the U.S. with the help of the Brazilian embassy. An article in Tie Bao from November 1946 said the C.P.C. brand was second only to Coca-Cola.

But the high times weren’t going to last forever.

In China, fortunes change fast

In 1946, Chang reportedly lost a lawsuit after making unwanted advances on a famous dancer. That same year, the C.P.C. Taishan Road location was closed, a premonition of much worse to come. After the Communist liberation of Shanghai in 1949, drinking coffee was increasingly looked down upon as a capitalistic bourgeois pastime.

In 1950, after returning to Shanghai from a business trip in Hong Kong, Chang Pao Cun was arrested and sentenced to three years in prison for “historical counter-revolutionary crimes.” His wife Fang Huiqin was left alone to raise their 10 children. Shortly after his release, Chang was sentenced to yet another 12 years for giving a private loan to one of his former employees, and sent to a labor camp in Qinghai.

In 1958, C.P.C. was changed to Shanghai Brand, and C.P.C. Coffee House became Shanghai Café, which remained open under government operation. By 1959, Chang’s Desheng Coffee Company had become fully nationalized and renamed Shanghai Coffee Factory.

Throughout the Cultural Revolution, coffee consumption was effectively banned, and canned coffee produced by the Shanghai Coffee Factory could only be bought at Western-style hotels. Ordinary people could not obtain it — only customers with foreign exchange certificates were able to purchase coffee beans or ground coffee.

The greatest luxury available to a few select Shanghainese was Shanghai Brand’s “Coffee Tea,” made with the leftovers of ground coffee beans mixed with sugar and pressed into cubes.

But then, in yet another twist, Shanghai Brand coffee eventually became one of the most recognizable “made in Shanghai” brands during the reforms of the late 1970s and early ’80s: coffee became a popular wedding gift. It was a mark of distinction for locals to have a shiny red can of Shanghai Brand coffee on their living room shelf.

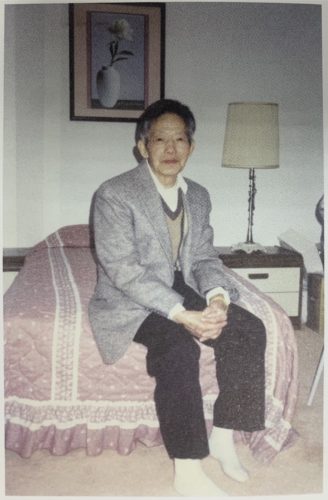

Even after his release from prison, Chang would not return to Shanghai until 1979, fearing further repercussions. The Bureau of Reclamation of Yunnan invited him in 1983 to serve as a technical consultant for the development of the local coffee industry.

Chang, then 69 years old, spent three years in Yunnan establishing the Yunling Coffee Company, which became the origin of self-produced coffee in modern China. In a stroke of tragic fate, his office was completely destroyed in a mysterious fire. The incident caused him to leave Yunnan with great sadness and return to Shanghai with a payment of merely 6,000 yuan (less than $1,000). Only much later did he learn that the facility he established and the people he trained in Yunnan ultimately became Hogood Coffee, now the largest domestic producer of instant coffee and a supplier to Nestlé.

After years of struggle and disappointment, Chang was finally officially rehabilitated in 1985, and parts of his family’s seized assets returned. His wife Huiqin subsequently moved to the United States in 1987, following one of their children who had emigrated to California. Chang stayed behind to give his “Chinese coffee dream” one more shot. At age 74, he invested all his money in a new coffee business with the intent to establish another coffee factory with a new partner. The plan failed, and Chang, once again, lost all of his savings. Reluctantly, he agreed to leave Shanghai for California in October 1991.

His timing was unfortunate. In the early 1990s, imported brands and instant coffee began penetrating the market, and the Shanghai Coffee Factory eventually stopped producing its hallmark canned coffee. Since 1988, the Shanghai Coffee Factory has been part of Meilin Co., the current owner and producer of another old Shanghai brand, the famous Aquarius Soda (正广和 zhèng guǎng hé) created by British businessmen Caldbeck & MacGregor in 1882.

In 2001, Shanghai Café on Nanjing West Road — the original C.P.C. Coffee House — was permanently closed. Remnants of the C.P.C. brand could be found in downtown Shanghai up until around 2016 at Shanghai Coffee Factory’s showroom, which prominently displayed “Desheng Coffee since 1935” on its signage. The location has since been closed, and Shanghai Coffee Factory only continues to exist as part of a website maintained by Meilin Aquarius, listing a few coffee-related products. It is unclear if the products are actually still in production, since no traces of them can be found in stores these days. No reference is made to its founders, Chang Pao Cun and Fang Huiqin, nor the original C.P.C. brand.

After suffering from a stroke in May 1992, Chang was hospitalized. According to his son, the septuagenarian regaled nurses from his hospital bed about his C.P.C. and shared his plans of restarting his coffee business in China. “The coffee king of Shanghai” died in California in July of that year. His wife, Fang Huiqin, passed away in 2015 at the age of 98. Their legacy lives on through one of their sons, Charles Zhang, who founded several multimillion-dollar businesses in food and beverage in the U.S.