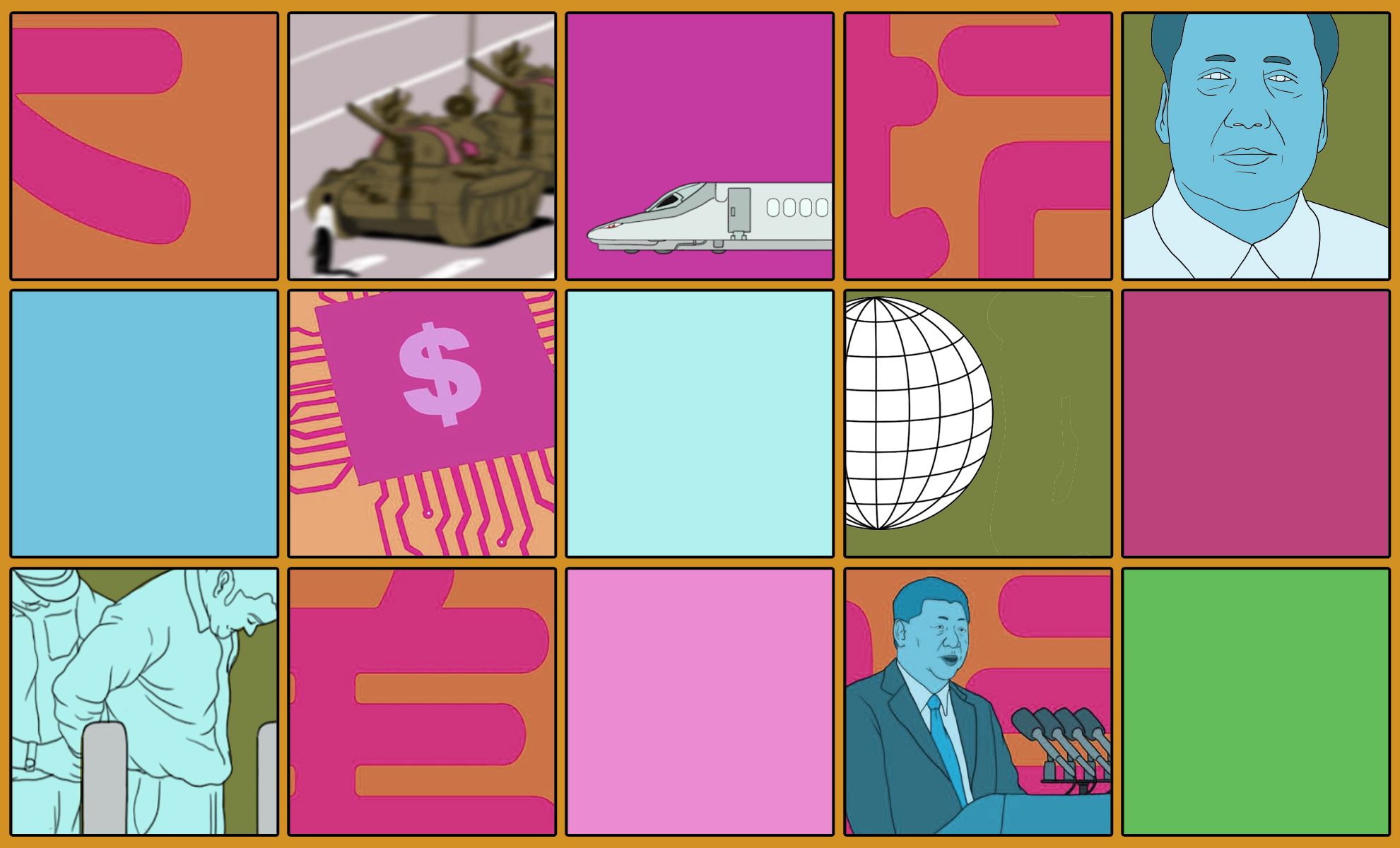

“There is something major afoot in China right now,” says Kaiser Kuo, but single-lens analysis that lacks empathy won’t cut it in providing insight into the complexity of the changes. What The China Project has called the Red New Deal could mark the start of a new phase in Chinese history, and it deserves to be taken seriously and seen from multiple perspectives.

[Editor’s note: The following is a lightly edited transcript of this week’s Sinica Podcast, a speech that Kaiser Kuo gave at the CHINA Town Hall 2021, an event by the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations.]

There is something major afoot in China right now. A tectonic shift, a serious recalibration, perhaps even a realignment of the Chinese Communist Party’s priorities. It may be that we are witnessing something really historic: the birth of a new development model for China. For over a year now, we’ve seen Beijing moving to rein in China’s big tech companies. It has ramped up antitrust actions. It has kneecapped the enormous cram school industry, it has completely banned cryptocurrency. It has limited real estate speculations. It’s imposed very strict limits on online games. It’s de-platformed all these celebrities. The list just goes on.

What is this all about? The outlines really have started to become clear to most observers just in the last three months or so. This weekend — just this past weekend — a leading Party magazine published a short essay by Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 himself, on the topic of “common prosperity,” which is the concept at the heart of the leadership’s new focus.

That essay has cleared up some questions about this thing that my colleagues and I have taken to calling the Red New Deal. But many questions remain unanswered, Xi’s essay still doesn’t offer concrete proposals or quantitative targets or a clear road map. While we can assume fairly broad buy-in within the very upper echelons of the Chinese political elite, it’s hard to establish how it’s all being received a little bit further down. We don’t know what it all means for the conduct of China’s foreign policy, for example, there’s likely to be very little consensus among analysts outside of China on what it’s going to mean even just for near term growth prospects or whether it’s going to be an adequate response to the daunting demographic challenges that China faces. We don’t know whether it means five more years of Xi Jinping or 10 more years or maybe more still.

The fact is, we all view what’s happening in China today, we will continue to view it through different lenses in combination. National security or geopolitics, human rights, the rights of marginalized communities, national or ethnic self-determination. The idea of an ideological contest between authoritarianism and democracy, sustainability and environmentalism, concern with human flourishing, concern with economic growth, either abstractly or as it directly affects your investment portfolio. The impact on American jobs, the impact on American consumers, and much, much more. We will arrive at different conclusions as to what’s driving this shift, different conclusions about its likely magnitude, the profundity of its impact, and what all this means for America. It will be, in other words, no different from all of our thinking and analysis on China. And that should tell us something. When we see all these competing narratives, we should recognize that the thing that we are looking at, China, is profoundly complex and we all need to be better informed.

Getting informed on what’s happening in China is, at once, much easier and much more difficult than it was just a decade ago. On the one hand, there are substantially more sources of English-language content about China than ever before. You’ve got all these major media outlets now devoting more and more column inches in every publication to the topic of China. You have a mad proliferation of podcasts and Substacks. On the other hand, there are far fewer reporters from American media outlets who are on the ground there. Due, of course, to these tit-for-tat restrictions and expulsions during the last year of the Trump administration. And owing in part to the COVID-19 pandemic, physical access for students and scholars has been greatly restricted. The arrival of impressively decent, freely accessible, AI-powered translation tools offers unprecedented access now to what Chinese people, real Chinese people, are thinking, saying, and writing.

But making sense of it, understanding what counts as an official position and what’s just a fringe opinion. Assessing the reliability or the representativeness of what we read online or trying to build in some adjustment for the censorship that we know to be there. None of this is easy, especially without the guidance of trained and seasoned specialists. We can’t pick out the melodies amid all that cacophony.

And yet, getting informed about China is more urgent than ever. Like it or not, China has loomed up in our national consciousness to become our great other, offering a challenge to the long-held, almost axiomatic, beliefs about ourselves, that really comprise American exceptionalism. China’s rise and the power that China now appears to possess have really called into question our ideas about the natural progression of history, about technology and innovation, about the operation of the free market. And for some, it’s even sown doubts about the inherent superiority of our democratic political system.

It seems like everything we do, everything we try to do of late, whether it’s passing an infrastructure plan or a budget or justifying the existence of NATO, whether it’s pulling out of Afghanistan or supplying vaccines to the developing world, it’s being done with China squarely in mind. So, even as President Biden frames this great global contest as one between democracy and authoritarianism, some Americans — and really they span the gamut from the progressive left to the very conservative right — openly praise and perhaps even pine after certain features of today’s archetypal authoritarian polity, China. Its seeming capacity for decisive action, for long-term planning, and for husbanding of resources to invest in durable infrastructure and human capacity. A perhaps enviable, certainly arguable, absence of this endless culture war that polarizes us and this partisan polarization with all of its hatreds, it seems to drain off American energy and American attention.

The other version of China, though, is one that dominates the American imagination. In this version, China is the opposite number in nearly every respect to our self-conception as Americans. China is communitarian, where we are individualistic. It’s totalitarian, where we are free. It’s planned and top-down, where we believe ourselves to be spontaneous and bottom-up. It’s repressive and even genocidal in its treatment of its ethnic minorities, while we empower and celebrate ours.

But to reduce China to simplistic binaries is utter folly. So, too, is viewing China through a single lens, the simplistic calculus of so-called realism, say just as an example, that one prominent American IR scholar insists upon in the latest issue of Foreign Affairs, which I just read before this talk and which was just appallingly wrong and dangerous. This is exactly why, especially at this moment, when wise policies to avoid war and to enable collaboration on issues of existential importance, why a new understanding is so urgently needed.

When we cast our China policy just in black and white, we become prone, on the one hand, to overestimating and exaggerating China’s capabilities — and just as worryingly, on the other hand, to vastly underestimating China. Looking only through a single lens or any polarizing and binary lens, we assuredly misread Chinese intentions and that is super important. We will remain completely unable to grasp how our actions are interpreted in Beijing unless we embrace a more complex view. We’ll be unable to think through the second-order effects of our policies and even of our rhetoric. We’re going to become perilously un self-reflective, locked into assumptions that will go unquestioned, questions that really, we need to answer more than ever, we need to keep asking ourselves about what American national interests actually are, about how the rest of the world, including our allies, sees us, our politics, our reliability, about our place in the world, what it is and what it ought to be.

We need to develop dragonfly eyes, to be able to see things from multiple simultaneous angles. And just as importantly, to be able to integrate all of those perspectives and process them without succumbing to the paralysis of confusion.

There is one perspective, vital to our understanding of China, that is too often left out and is the Chinese perspective. Yes, of course, there are multiple Chinese perspectives and that is important, absolutely, to keep in mind but don’t let that stop you from trying to understand the view from behind the eyes of your counterpart in China. That Chinese college student or that educated urbanite, that political elite, or if you’d rather, just some notional average Chinese or ordinary Chinese citizen. We all understand this concept of empathy and except for some rare non-neurotypical folks, we all possess it. And while regular old empathy, what they call emotional empathy, might work when extended to people who are like us in our own society with whom we have a lot in common, socially, culturally experientially, and so forth.

It’s just not enough when you’re trying to get inside the head of someone from a very different culture or society, like the Chinese. Sure, we are all human. But we were taught very different things in school. We were socialized differently, we relate to our history differently. We were brought up on entirely separate vocabularies of historical and mythological archetypes. We have quite separate pantheons of heroes and of villains, quite distinct corpora of fables and fairy tales that we were all raised on. With vastly different experiences of the world, it shouldn’t surprise us that we have quite a bit of psychological distance from one another, we and the Chinese. But with enough knowledge, we can imagine it. We, human beings, come equipped with the ability to do this, to put ourselves in that headspace. And if we’ve taken the time to understand the very different influences, the assumptions, the values, the habits of mind, to populate it, not with precisely the same mental furnishings that the Chinese have but, at least, something that’s a decent representation, that’s going to take us a whole lot closer to understanding how they think.

Now, the fancy name for this kind of empathy is cognitive empathy, I generally prefer to call it “informed empathy.” And it doesn’t require us to abdicate our own values, not at all. Even if you insist on seeing China as an enemy or thinking of China as an enemy, surely, if you hope to prevail, you have to know how that enemy thinks. So, spend some time inside China’s head, come to an appreciation for why the mental furnishings are as they are. Really see how the world looks when you look out through those eyes and I’m confident that you will come away, maybe no longer thinking of China as the enemy. It does require us to know something about the other, as I’ve said. That takes real work, that not all of us have the luxury of the time to put in. What takes much less work though, is to learn to recognize when someone else has made that effort and does apply that informed empathy to her analysis of China. Those are the perspectives you should value.

Equally important, learn to recognize when that quality is absent, right? Those who show no evidence of that empathy, who can’t be bothered with describing or trying to describe the view out Chinese window, China’s windows, their analysis should be discounted, accordingly. Not ignored, necessarily, but steeply discounted.

If there is one thing to try to keep firmly in mind when trying to practice cognitive empathy, informed empathy, with China, it is this, always remember how rapid and compressed the whole experience of modernization has been for China. This means a couple of things. First, it means that, for hundreds of millions of Chinese people alive today, the chaos of the Cultural Revolution is still very much a part of living memory. For many more still, it means that poverty is a living memory and for some of those, even literal starvation is a living memory.

It also means that a Chinese person starting her first job after graduating junior high or high school, at the dawn of the Reform and Opening period, when China’s per capita GDP was still less than $200, is thinking about retiring only now — when China’s per capita GDP is over $10,000. It means that the great majority of people under 40 today cannot remember a time when their lives haven’t materially improved year to year or even day to day. And that they feel a natural pride in their nation’s accomplishments. They recognize that this has been made possible by market reforms, by opening to the world, and the release of pent-up entrepreneurial energies. But they also recognize that it’s been made possible by a state that has made some wise investments, has preserved stability. So, more so than Americans, Chinese tend to believe that their government actually can steer the country wisely into an uncertain future. More so than Americans, they view technology, which by the way, has developed in lockstep with their improving lives, as a positive force and not one to be feared.

The breakneck compressed nature of China’s single generation rise also explains why, despite the manifest evidence of China’s modernization, the dazzling infrastructure, the gleaming forests of skyscrapers, the high-speed rail networks, why China can still be so thin-skinned and sensitive to perceived sleights. This is, after all, still brand new. It sometimes seems to me that it’s like Tom Hanks in the movie Big, China went to bed as an 11-year-old and woke up in the body of an adult. I mean, this is no slight, it’s just that the software hasn’t caught up with the hardware. So, with this firmly in mind, let’s talk about what’s happening now in China, this tectonic shift I talked about earlier, and try to see it from a Chinese perspective.

First off, there are some things that I am confident in asserting that it is clearly not. First of all, it is not a revival of the Cultural Revolution, for all that you may have heard. That still haunts many Chinese and the very China they know and cherish today was built on the repudiation of that period’s excesses. It’s not the end of market liberalization in all forms. They will scale it back. Certainly, this is a reaction to what they see as excesses of neoliberalism. But the contributions of the market are just too conspicuous. It’s not the return of centrally planned command economics.

So, what is happening? My current hypothesis goes something like this: Xi Jinping’s administration has concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic constituted something of a stress test of China’s economy, of its state capacity and its regime legitimacy and it passed. It survived the public anger over the muzzling of Li Wenliang, the Wuhan ophthalmologist, who tried to bring attention to the transmissibility of the then-novel coronavirus. Something many regarded, especially after Li Wenliang died, as China’s “Chernobyl moment.”

It imposed harsh stay-at-home orders and continued to restrict movement for many months, with checkpoints everywhere, very tight quarantines. It deliberately cratered its economy. As the first country to experience the outbreak, it was the first also to undergo a national economic shutdown in the spring of 2020. It did more than just flatten the curve at high cost, it basically stamped out the virus in China. And it reopened without a second wave, without a big Delta surge and it was the only major economy that did not contract in 2020. The big takeaway seems to have been that, China and the Party can endure significant short-term pain and can reap substantial long-term gain. Whether this is, in fact, the case and I personally believe there’s quite strong evidence for it. Beijing’s leaders believe they emerged with even greater regime legitimacy and with proven state capacity and with a healthy balance in the political capital bank account.

Even the blame that was aimed at China from abroad, whether the so-called lab leak theory or even darker imputations of intentionality that came from, for example, the United States, they seemed to have produced a rallying round the flag, kind of, effect. Actually, a shot in the arm for patriotic confidence in the Party leadership. The other crisis that crested during these COVID years, growing condemnation over China’s mass extralegal detention of Uyghurs, the imposition of the National Security Law in Hong Kong. They ironically appeared to have contributed even more to this sense of national or defensiveness and possibly of confidence. All this, of course, was bolstered by the inevitable comparisons to the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Which is, of course, China’s own great other and its loudest critic. It watched as the United States fell into even worse hyper-partisan polarization. It wasn’t hard to guess one country, at least, that Xi Jinping had in mind when he wrote in that essay published last Saturday in Qiushi, that some countries are experiencing the collapse of the middle class, wealth inequality, political polarization, and the spread of populism.

So, if I’m right, Beijing has concluded that, if there was ever a time to break some eggs and make an omelet, to pull off the bandaids, whatever metaphor you want to deploy here, that time is now. So far that seems to mean, deflating asset bubbles, especially in real estate, aggressive de-leveraging, radical steps to curb the power of tech platforms by restricting their access, for example, to data and neutering their very powerful algorithms. Squashing speculation, whether in real estate or in cryptocurrency. And even if it means destroying billions of dollars of shareholder value, which it did, killing off an entire industry, an industry that Beijing believed was exacerbating inequality of educational outcomes, after-school tutoring or cram schools. It’s looking to me like a calculated act of Schumpeterian “creative destruction.” Unclear is whether moves like this, any of these moves or maybe the national property tax that’s now being floated, will prove to be a bridge too far.

We call this the Red New Deal, in part, because it has, sort of, an ostensible vision that seems to share many features with the Green New Deal. It wants to create jobs in cleantech, to remake the economy to be more sustainable and more fair. To emphasize the core industries of the so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution. It is red, of course, because it will inevitably draw on the Party rhetoric, if not the actual ideology, in hopes of restoring some class consciousness and restoring dignity to the beleaguered working class. Of course, we could be very wrong, I could be very wrong or Beijing could be very wrong. Whatever the case, it is a consequential matter, a serious matter, so take it seriously and get informed.

Be aware of the lens or lenses that you tend to take up when you think about China and be aware of their limitations. Be aware also that what you think you know — unless you’re somebody who studies China professionally and has spent many, many long years working there or living there — what you think you know comes to you filtered through the lens of the media, which has its own built-in structural, almost ineradicable distortions. Understand, at least, the optical properties of that lens and above all, when you do think about China, whatever lens you select by habit, add one, add that crucial one, the one that says, what are the Chinese thinking? How do the Chinese people themselves perceive what is happening? How are Chinese people themselves, people from different walks of life, different genders, different ethnicities, urban, rural, older, younger, how are they experiencing and reacting to this?

That, after all, is going to determine the appeal of alternatives. It’ll determine how hard they fight to defend it or to resist it. Because some will certainly resist it. The social conservatism that marks this new phase of politics in China will be repulsive to many, not just in the West but also in China. Mark my word, I know, I personally find it beyond distasteful that all this laudable language about common prosperity has been accompanied, in speeches by Xi and other senior Party officials, by rhetoric about “sissy men” and has been matched by this assertion of heteronormativity in policy as well. The paternalism, the bans on games, the new moralism in entertainment, all that stuff. It’s doubtless it’s going to stick in the craw of many Americans, even if they believe that it is ultimately well-intentioned.

A Chinese-American friend of mine recently wrote, of the Chinese government, “A moral entity that genuinely cares about people under them but doesn’t trust them with power and tries to make all their welfare decisions for them, is probably really foreign to Western liberal sensibility but pretty familiar to anyone with Asian parents.” This was, of course, intended to be humorous but there is a serious claim in it as well, and it is anchored in this idea that the Chinese perspective on this, the Chinese reaction, that’s going to matter most. Now, zooming out from this set of policies, this Red New Deal or whatever we’ll end up calling it, there’s even more significant change happening right now, in our time, that I really believe needs to be understood.

One of the great intellectual historians of modern China was an American scholar named Joseph Levenson, who published a monumental work in three parts, called Confucian China and Its Modern Fate, before his tragic death in 1969. He is really highly regarded. He conceived of a way for us to think about what intellectual history really is. His framing, his ideas of modern Chinese intellectual history, have had a profound effect on me. Intellectual history is all about ideas and the intellectuals who hatch them, who think them. An idea, Levenson said, is really an answer to a question — and implicitly a repudiation of all the other possible answers to that same question. So, from the jarring encounter that China first had with the modernized West, some would date this say, to the opening salvos of the Opium War in 1839. And for the 180 years that followed, virtually every intellectual movement, every social theory, every -ism and -ology that Chinese intellectuals either held up or cast down, that they killed for, that they died for, these were all efforts to answer one central question. And that was how to create national wealth and power.

Any answer that modern Chinese might eventually settle on, any ideology, any system of thought, any approach to politics, they would have to succeed, not only in making the nation wealthy and powerful but it would also have to resolve a really fundamental tension. It would have to be both mine — that is, would have to be emotionally satisfying to me as a Chinese person, to accord with history and to feel as though it were Chinese — and it would have to be true, that is, it would have to accord with the world of facts, the world that unsentimental Chinese saw when they looked out at the world around them. It would have to accord intellectually then, with value. I would submit that China right now, for better or for worse, is closer than it has ever been, in this last 180 years, to an answer to that question. China has now attained both wealth and power, with the exception of outer… Well, the Chinese, some people call, outer Mongolia and Taiwan, neither of which the PRC ever actually ruled.

It has established firm sovereignty over the geography of the old Qing empire, to which it sees itself as a successor state. Again, for better or for worse. It has found, in this hybrid system of Confucian, Leninist, state capitalism, something that a critical mass of Chinese people are satisfied is both mine, Chinese, or at least imbued with sufficient Chinese characteristics and true because it seems to have really delivered the goods. To be sure, I don’t believe we are going to see China’s leadership just rest on its laurels, that it believes it’s done with the quest for wealth and power. Doubtless, the continued accretion and preservation is going to be on Beijing’s mind for the foreseeable future, nor are Beijing’s leaders perfectly confident that China has really settled comfortably into a finished identity, that all tensions are resolved. Not at all. They shouldn’t be confident in that.

For such a powerful nation, it’s still so strikingly thin-skinned, right? It really hasn’t been too long since the foreign ministry stopped using this expression, “hurt the feelings of the Chinese people,” as it once did really, really often. But look closely at the changing nature of Chinese nationalism. As one friend of mine put it in a conversation with me, in conversations with Westerners, Chinese people are no longer just complaining about unfair or biased media treatment, no longer just on the defensive. They are saying, with greater frequency, “Sit down and listen. I have something to tell you.” A critical mass is now across the line and my distinct sense is that the great question of modern China’s history has been, at least, from the perspective of a great many Chinese people, is finally put to rest. If this is the case, then what we’re seeing right now is a transition to something beyond modern Chinese history.

Were it not for one chastening example, I might be tempted to talk about an “end of modern Chinese history.” But perhaps we could just meaningfully call it the “beginning of postmodern Chinese history.” If China’s modern history was defined by the great question of, how to attain wealth and power, and if the fundamental tension that bedeviled Chinese for nearly two centuries was, “how to create a China that is, at once, Chinese and modern, modern but not Western, fundamentally mine and fundamentally true,” what will the questions and the tensions in this new period of China’s history, what will they be? The new questions that are already being asked, I believe, are of the sort, what kind of power should China be in the world? There’s less exigency in this, less amoral pragmatism, less means and more end in that question. It’s more normative. How should a newly powerful and materially comfortable China behave?

Now, what’s really interesting is that, in a sense, we are all now trying to answer the same question. We, Americans, people of many nations, are all wondering, what kind of power is China going to be? And as we try to answer that question, well, at least, we’re on the same page. As we try to answer that question and as China does the same, we must keep some things firmly in mind. We have to take seriously what China and its leaders say but without assuming that China will always do what China says it will do. We must not believe that China is 10 feet tall and that it can impose its will on the world, on the region, or even on itself. It can’t impose the vision that its leaders articulate necessarily on any of these.

And we must rise to the challenge that China does present without foreclosing the possibility of enduring peaceful coexistence. That will require a dialing down of American hubris. It will require us to try much harder to come to a multidimensional understanding, one that can recognize, accept, and process all the vexing contradictions, all the complexities of China. Thank you very much.