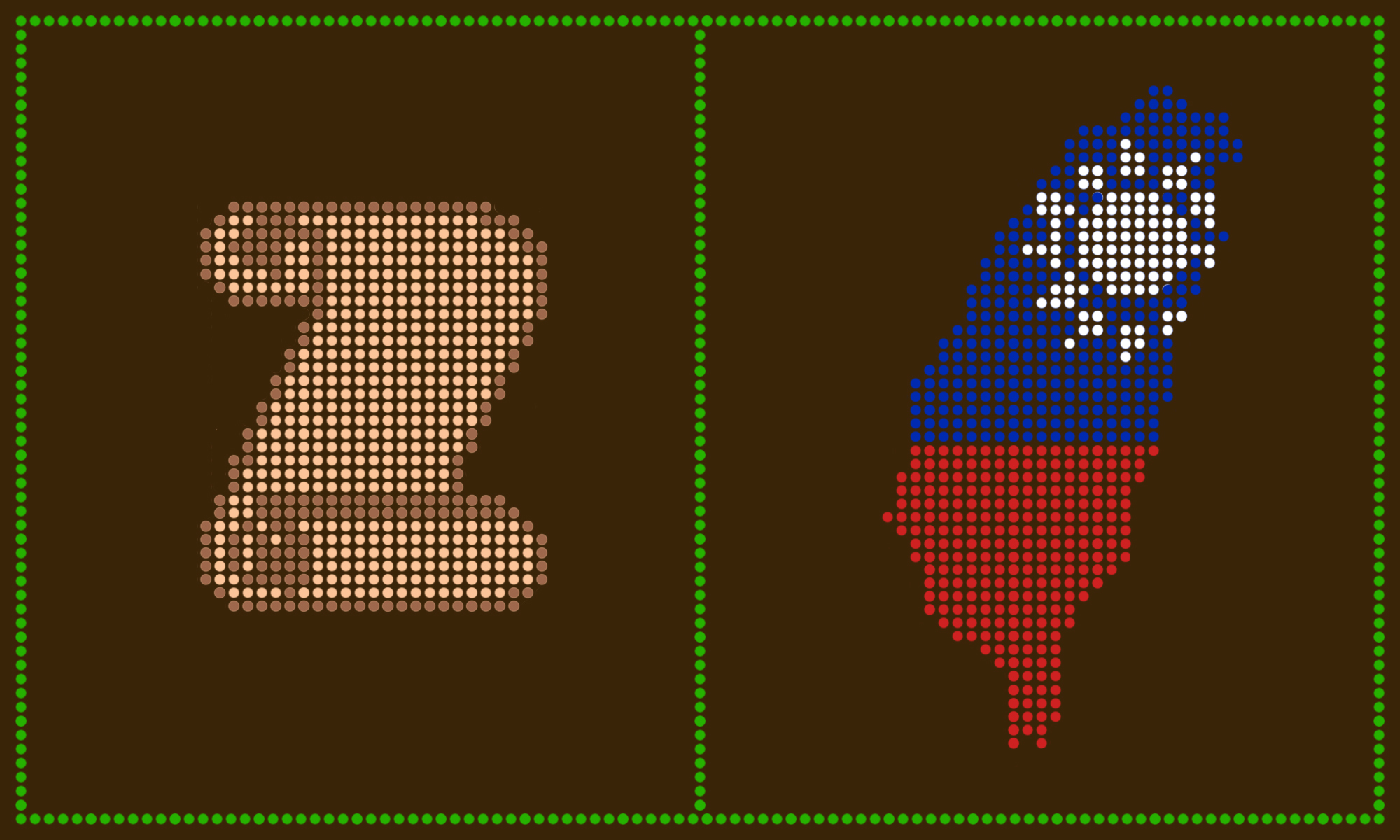

Taiwan parties split over constitutional reform

After a month of increasing tensions, a proposal to amend Taiwan’s constitution may further strain the cross-strait relationship.

On October 22, a group of 17 former and current legislators who form the ruling Democratic Progressive Party’s (DPP) constitutional reform small group released a proposal for amending Taiwan’s 74-year-old constitution. Six reforms were announced, including lowering the voting age to 18, abolishing both the Control and Examination Yuan (the country’s auditor and civil service exam institutions), and establishing an independent human rights committee.

But the proposal that has sparked the most discussion is the one that is most unlikely to pass: lowering the requirements to amend the constitution in the future. This has been one of the principal demands of Taiwan’s independence movement since its martial law period, with an eye on eventually creating a new constitution.

During martial law, various groups in the underground independence movement drafted new constitutions as a way to imagine a Taiwan no longer connected to the Republic of China (ROC). As a result, forces opposed to independence are suspicious of constitutional reform, perceiving it as secessionist. Until 1991, any mention of constitutional reform was illegal under Article 100 of the Criminal Law Code.

“The constitution is directly related to the question of sovereignty. Because of this, it inevitably touches the question of independence or reunification,” says Chen Li-fu (陈俐甫 Chén Lìfǔ), a professor at Aletheia University and member of the Nationwide Constitution Reform Alliance (全国宪改联盟 quánguó xiàn gǎi liánméng). The alliance formed during the Ma Ying-jeou (马英九 Mǎ Yīngjiǔ) administration to push through constitutional reforms after the 2014 Sunflower Movement. While that effort failed, various civil society groups continue to pursue amending the constitution as an avenue for advancing democracy.

“[China] resolutely opposes any path that seeks independence through amending [Taiwan’s] constitution,” Mǎ Xiǎoguāng 马晓光, a spokesman for China’s Taiwan Affairs Office, said in response to the current proposal. “This includes lowering the threshold in order to open a convenient door to seek independence.”

Pushback also sprang up within Taiwan. Fai Hrong-tai (费鸿泰 Fèi Hóngtài), leader of the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) legislative caucus, said all portions of the amendment proposal can be discussed except for lowering the amendment threshold.

“The constitution is a big issue for the country,” he said. “If you lower the threshold [for amending it], afterwards in one day the constitution can be changed, and the people will be left divided.”

Fai also criticized the DPP’s process as undemocratic because it did not call for a national conference (国是会议 guó shì huìyì), a type of irregular protocol that brings in stakeholders from across the political spectrum to discuss key issues facing the country. Since democratization, all seven constitutional amendment efforts have used this protocol.

How did we get here?

In October 2020, a proposal for constitutional reform was introduced in the Legislative Yuan, Taiwan’s parliament, by DPP legislator Chen Ting-Fei (陈亭妃 Chén Tíngfēi). It was supported by her faction, the pro-independence 正常国家促进会 zhèngcháng guójiā cùjìn huì. Chen’s proposal included eliminating the constitution’s call for eventual reunification, delineating the state’s territory as only that under its current control, and the removal of all provincial-level governments. These reforms would have turned Taiwan into a de jure independent state, shedding its constitutional ties to China. The KMT rejected the proposal.

In response to the pressure for constitutional reform, the DPP formed a small group in March composed of a balance of the party’s various factions. The party called for an uncontroversial reform process, with Ker Chien-ming (柯建铭 Kē Jiànmíng), head of the DPP’s legislative caucus, saying that the party “wouldn’t walk an extreme path.”

Taiwan’s constitution is the constitution of the ROC, which was ratified in 1947 on the mainland. In 1948, due to the Chinese Civil War, the KMT altered the constitution by adding the “Temporary Provisions Against Communist Rebellion,” which effectively nullified the document, entrenched martial law, and turned the ROC into a one-party state led by the KMT. Although martial law was ended by executive action in 1987, the provisions remained in force, continuing to restrict civil rights and the development of a constitutional system.

“The ROC constitution is one of a totalitarian country,” says Chen, the professor at Aletheia University. He says the current constitution is insufficient to meet the needs of a democratic Taiwan.

Following the end of martial law, two choices materialized: amending the current constitution, or drafting a new one. The latter option was mostly supported by those in the independence movement, but that movement was weak. At the time, the KMT-controlled National Assembly, a now-defunct legislative institution, was responsible for amending the constitution. In 1991, it enacted the “Additional Articles of the Constitution of the Republic of China,” which ended the temporary provisions and allowed the gradual process of building a new constitutional structure to begin. The constitution has since been amended seven times, with 12 articles added. Reforms have included important structural changes like the direct election of the president, term limits, and the beginning of legislative elections for the “free areas” of the country, or the ones under the administration of Taiwan’s government.

The last time the constitution was amended was in 2004 during the Chen Shui-bian (陈水扁 Chén Shuǐbiǎn) administration. At the time, Chen and the DPP wanted to halve the seats in the Legislative Yuan, Taiwan’s legislature, and enact a single-member district voting system. However, the KMT had a majority in the Legislative Yuan, forcing the DPP to acquiesce to its demand to make amending the constitution more difficult.

According to Article 12 of the Additional Articles, amending the constitution requires at least three-fourths of the Legislative Yuan to participate in a vote, and then three-fourths of the members present to actually pass the vote. Then there must be a six-month period for public comment before it must pass a referendum by obtaining at least 50% of the votes cast in the previous presidential election.

That means that not only would the DPP need a significant number of KMT legislators’ support to push the proposed reforms through the legislature, but also more than 9.6 million votes from the public, since 19.3 million people registered to vote in the 2020 presidential election. For context, Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文 Cài Yīngwén) won the presidency with a record-breaking vote tally of 8.2 million votes — more than a million short of the total needed to amend the constitution.

The KMT’s current chairman, Eric Chu (朱立伦 Zhū Lìlún), was chairman when the party thwarted the last attempt at constitutional reform in 2015. It is unlikely he will work with the DPP ahead of crucial district elections in 2022.

“Most of the chatter about constitutional reforms right now is unrealistic,” says Kharis Templeman, a researcher at Stanford’s Hoover Institute. “The only changes that have a chance of passage will require a cross-party consensus, so if the KMT isn’t on board nothing will happen.”

According to the office of DPP legislative caucus head Ker Chien-ming, the full details of the six reform measures have yet to be finalized. This is expected to occur over the coming weeks before the proposal is submitted for deliberation in the Legislative Yuan.

Many remain unsatisfied with the proposal. Professor Chen at Aletheia University believes that Taiwan needs far more radical reforms to its constitution to become a stronger democracy. He says the ROC constitution is based on Sun Yat-sen’s (孫中山 Sūn Zhōngshān) Three Principles of the People, which was developed in order to bring Chinese society together in opposition to imperialism. In contrast, most modern liberal democratic systems are based on checks and balances, to ensure that one branch does not become excessively powerful, and therefore protecting the rights of the people. He says that while the ROC constitution was possibly appropriate when it was created, its essence does not match Taiwan’s current historical moment.

Chen maintains that only a new constitution is appropriate for Taiwan’s current historical moment.

“Whether it is under the name the Republic of China or the Republic of Taiwan, we can’t use a 70-year-old constitution to meet the needs of today’s Taiwanese society,” he says.