Life after China: Catching up with Mark Kitto

He's been a soldier, a metals trader, a publisher, a hotelier, and now an actor. "I’m a firm believer that you’ve got one life and you’ve got to live it," Mark Kitto says. "I don’t think I ever wanted to be a one-track career person."

For China expats of a certain era, Mark Kitto’s story — if not the man himself — is well known. But his story since leaving China has been just as interesting, involving a new career as an actor and spending much of this past year performing in Chinese Boxing, a one-man play he wrote set during the Boxer Rebellion of 1900.

After studying Chinese at London University’s School of African Studies (SOAS), and a stint in the Welsh Guards, Mark Kitto moved to China in 1996, where he became a Guangzhou-based metals trader. Living through a period of unprecedented economic growth and social transformation, Kitto went on to establish That’s, an English-language listings magazine with Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou editions.

In 2004, after seven years building a national publishing empire, Kitto says it was seized by his state-affiliated competitors. The experience is chronicled in his tell-all memoir That’s China, published in 2017. After leaving publishing, Kitto went on to run a café and guesthouse in a European-style villa on Moganshan, a verdant mountain retreat where Shanghai-based foreigners built summer houses in the 1880s. He wrote about his life in rural Zhejiang province in China Cuckoo (2012).

In 2013, Kitto left China with his family, writing his now-infamous “Why I left China” piece for Prospect Magazine that spawned a dozen (often bad) imitation essays. “I have fallen out of love, woken from my China Dream,” he wrote, prophesying social upheaval and economic vicissitude for China. He relocated to Norwich, England where he has since established an events listing paper for holiday cottage guests and other visitors to North Norfolk.

He recently spoke with The China Project about his time in China, what inspired him to write Chinese Boxing, and how he came to be “canceled” in the UK.

You recount in your memoir That’s China some of your experiences during your “year abroad” in Beijing in 1986, but what led you to study Chinese in the first place?

At prep school, I had an inspiring language teacher, Mr Galsworthy. He had the wonderful linguistic advice, “If you don’t know the word, stick in jam doughnut and come back to it.” Under his stewardship I won a scholarship to Stowe with my Greek and Latin. There, at a fairly young age, I began to wonder what life was all about. My mother gave me a biography of the Dalai Lama. I was fascinated, verging on obsessed, by Tibetan Buddhism. There were some great books in the library, including various accounts of exploration by the likes of Heinrich Harrer (Seven Years in Tibet,1952). My housemaster Roger Potter led school expeditions to Nepal and he allowed me to go on an expedition when I was too young, and perhaps impressionable. So I put together my fondness — not natural ability, I stress — for studying foreign languages, and interest in Tibet, Buddhism, and the East. By the time it came to apply for university, Dèng Xiǎopíng 邓小平 was saying he was going to open up China — hence why I opted for Chinese at SOAS.

Although you began publishing magazines in South China with Clueless in Guangzhou, you soon moved your headquarters to Shanghai. Why did you make Shanghai your base?

Beijing was, and is, the cultural and political center. Guangzhou is the true trading center. Shanghai was, from 1850 or so, the international center. But the CCP (Chinese Communist Party) hated the place. They saw the Shanghainese as traitors. Chiang Kai-shek and his gangs had massacred the Commies there in 1927. And they had always worked for foreigners. So [after 1949] the CCP essentially left Shanghai in the dark ages. But in the ’90s, foreigners actually wanted to come live and work in China. The CCP didn’t want too many of them in Guangzhou except for trade, as it is too far south. And they didn’t want them in Beijing either, too close to the heartland. Suddenly they realized they had a foreign-built city, which they’d left to rot. Shanghai is the biggest honey trap ever. And the laowai suckers loved it. They came there in their droves and the city took off. Put simply, Shanghai in the late-’90s and early-2000s was on speed.

The author Paul French, in an interview with Alec Ash, included Wei Hui’s controversial first book Shanghai Baby in his list of recommended Shanghai novels. Do you think her sexually-charged romp captured what it was like to live in Shanghai at that time?

I’m not sure about that exactly, but I knew Wei Hui and her arch rival Mian Mian (author of Candy, 2003). Their whole approach to literature was to basically live as crazy a life as possible and then write about it, which I suppose does represent what was happening in the city back then. I had a bit of a thing with both of them at various points and that made them furiously jealous. They even had a cat fight over me on Maoming Lu [Street] one night. I wouldn’t want to suggest that I was any sort of Casanova or anything, but I had a certain notoriety. Incidentally, the obscured foreigner on the cover on the Japanese edition of Shanghai Baby is actually me.

After losing your magazine business, you established a café and guesthouse on Moganshan. You looked to be living a pretty idyllic life. One review of China Cuckoo said it “resonates with gentle echoes of Peter Mayle’s A Year in Provence.” Why give it all up?

Moganshan is a great tragedy. It’s burdened by history, the fact that it was built by foreigners greatly concerns the local government. I don’t know how many hundreds of those beautiful villas are up there that could be restored and used. It’s a fantastic scenic spot and could have been a thriving resort village. But to achieve that you have to allow something like a free market. Instead, they’re just left to decay, it’s a ghost town. Meanwhile, in the foothills there’s a plethora of farmhouse BnBs (农家乐 nóngjiālè) and resorts like Naked Retreats, and their imitators, doing really good business.

Your article for Prospect Magazine titled “You will never be Chinese” went viral in 2013. But some criticized it, claiming you were “making a career out of leaving China” and “stating the obvious” in the title. How would you respond to such criticisms?

As for the first point, well, I’ve left China, OK. As for the second, let me put it this way: I had a fascinating conversation with a journalist in Australia. He was interviewing me about my book and in absolute seriousness, he said to me, well you’ve been in China for 18 years, so you must have a Chinese passport. I had to explain that no, I didn’t, that this doesn’t happen, and he was really surprised. From an Australian point of view, anyone can be Australian, just as anyone can become American or British. That’s what I was trying to say in the article. No matter how hard you try you’ll always be an outsider.

In the Prospect article you also made some bold predictions about China’s coming misfortunes. Eight years on, during which China has continued to develop rapidly, do you stand by your convictions?

I think I hit the nail on the head. One of the things I wrote about is the property market, and look at what’s been happening with Evergrande. Prices are coming down, which could lead to social unrest as people become poorer. The attacks on big tech, celebrities, and crackdown on education show that the sacred contract between the Party and the people — which said you can get rich as long as you stay out of politics — has been broken. This Chinese economic miracle notion is a charade. Of course you’re going to get exponential growth when you’re starting from zero, which is where the Communist Party put the people to start with. Basically, the world is waking up to the incredible scam that the Party has pulled off. There will be some sort of upheaval in China. I’m very concerned that the Party will distract the people by trying to seize Taiwan or something like that so they can justify their position for another few years. But the great hope is that the Chinese people are not stupid and they will see through it.

What have been the challenges in moving back to the UK?

There are some things that are difficult to get used to. It’s hard to define. I think there’s a certain hardness to the British, a sort of aggressiveness. As a society, we’re quite defensive and therefore we get quite aggressive. You know, aggression is the best form of defense. Sometimes on the street you get a sense that people are thinking “What are you looking at?” or “Why are you talking to me?” And in China there’s a softness, a gentleness to interactions, certainly in commerce. The fact they’re being very polite and lying through their teeth and preparing to stab you in the back is another thing altogether.

So you are glad to be back in Britain then?

Yes, of course, my little business hasn’t been ripped off or copied. I haven’t had the local council kick my door down and try to fine me because I’ve upset someone who’s given them a call. I don’t need a VPN, and I can read anything. Just after coming back I was completely addicted to BBC Radio 4 and listening to people talking about whatever and arguing in public and asking hard questions and criticizing the government. Again, it sounds naive, but you really miss that in China. Plus, I have to say the arts in England are incredibly vibrant.

Having moved back to Norwich and started a business, isn’t it a bit of a strange move to get into acting aged 50?

Actually, I did a lot of drama at school and had hoped to pick it up again at university, but SOAS is small and not that kind of place. I did get a role playing the stupid foreigner in a Chinese play, Gǔpiào de Yuánfèn 股票的缘分 — Fate of the Stocks. It was the third in a series of plays commissioned by premier Zhū Róngjī 朱镕基 to educate the masses about the free market. I played a foreign expert who helps a textile company in Shanghai go public and in the meantime has an affair with the factory boss woman. We went to Beijing to do a command performance for Zhu and co. I got the handshake photo. That was it for China, although I did see my fair share of “drama.” Back in Britain I started with amateur dramatics, took acting classes, and now I have an agent. 2018 was a great year. I was in Soldier On about PTSD and leaving the forces, with the Soldiers Arts Academy. I got a name check in the Sunday Times for that. In the summer I was the understudy for Pressure by David Haig in the West End. Next, I played Uncle Osborne in Journey’s End, a highlight of my acting career. Then in 2019 I was filmmaking in India. Sye Raa Narasimha Reddy is set in the 1850s, it is basically a Robin Hood story. I was the Sheriff of Nottingham’s boss who kicks his arse for not catching the Indian bandit.

How did the COVID-19 pandemic impact your acting career?

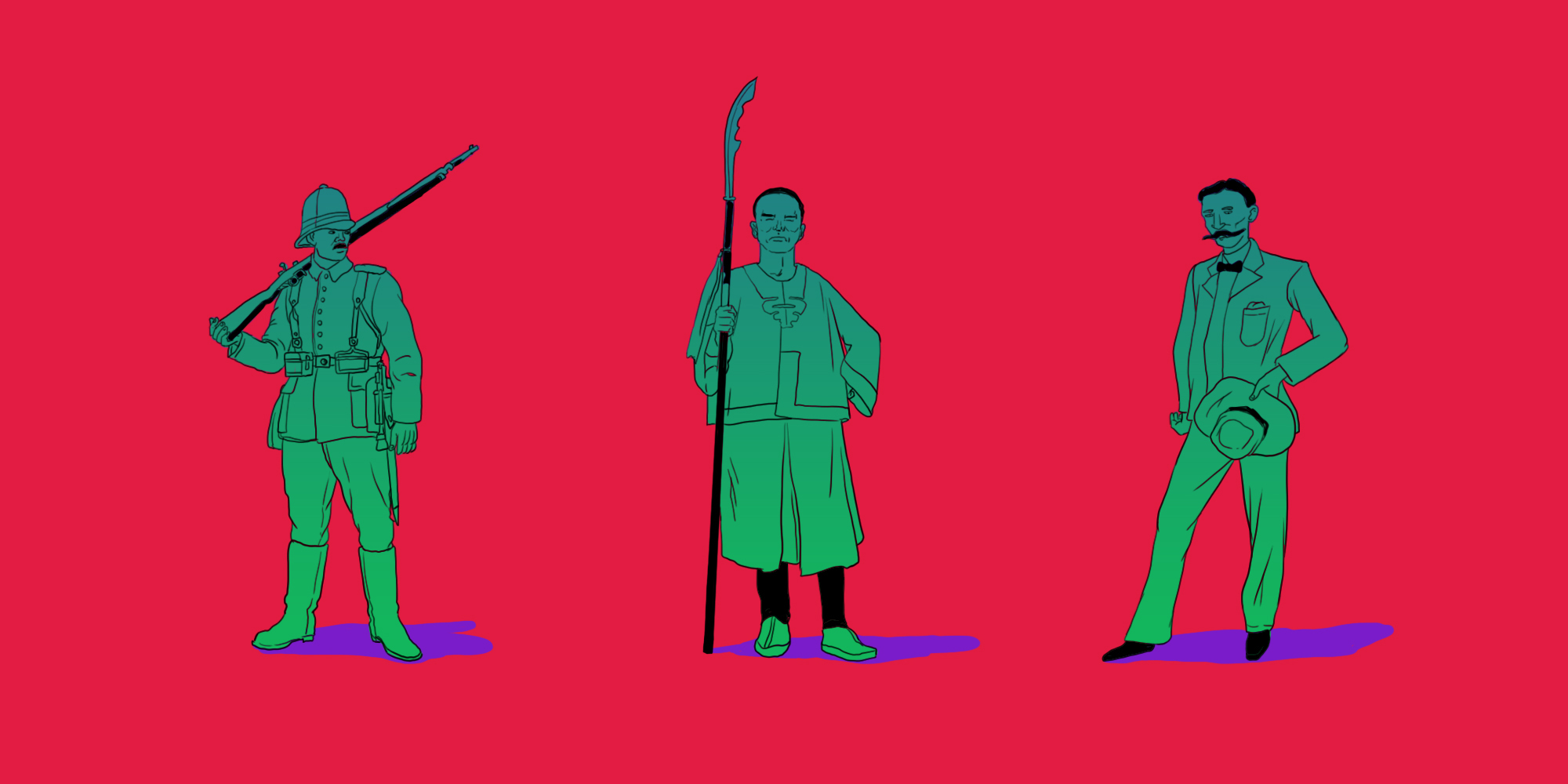

Just before COVID I was in the running for a one-man show. And then everything stopped. A friend of mine suggested I write my own one-man show — I think she expected me to come up with a crowd pleaser. But I started to think about the wumao [China’s freelance army of online trolls] who enjoy support from the government, which suddenly reminded me of the Boxers [an anti-foreign peasant army] who were backed by the Qing. It resonated, and I thought about how to convey the present tensions between China and the West, which are nothing new, how they go right back. You know, to understand China, you’d better read its history. So I wrote a play about the [Boxer] Rebellion. In it I play Sir Claude MacDonald, the former minister plenipotentiary to Peking; Ronglu, the imperial commissioner in charge of military training and commander of the Beijing Garrison; and Sargent Frank Richards of the 2nd Battalion Royal Welch Fusiliers, who were part of the relief force for the siege at Peking.

Were you concerned about playing a Chinese character, given it might rekindle images associated with “yellow peril” cinema when white actors would dress up to play Fu Manchu?

Absolutely. I was very conscious and I deliberately avoided making Ronglu into a caricature. I don’t play him with an accent. I do a few lines in Mandarin to establish I know China, and Chinese, early on. It’s played in about 15 small theaters, including Holkham Hall and Maddermarket Norwich. The Sheringham Little Theater in Norfolk canceled it at the last minute due to their “anti-racism” policy. They had all the materials ahead of time. Their reasoning was, they were in line for an anti-racism award and to have me portraying a Chinese character would risk them getting this award, which I think is outrageous. I think theaters are about putting on shows that make people think and challenge them. They have since apologized and clarified that they do not think I am racist. And the feedback, otherwise, has been great. The Q&A sessions after the performance can get really lively. I had three Chinese people come to a show and they loved it. I hope more come, even the Chinese ambassador to Britain, now that would be something.

You’ve been a soldier, a metals trader, a publisher, a hotelier, and now an actor. It’s like you’ve lived nine lives. How do these seemingly divergent occupations link together?

Well, of course there’s a connection, they’re connected by me. I’m a firm believer that you’ve got one life and you’ve got to live it. I don’t think I ever wanted to be a one-track career person, an English version of the Japanese salary man. I think that is a life not well lived. You know, in December, I am off to India to play Sir Stanley Rous, who was president of FIFA in the 1960s and ’70s in a Bollywood production. Things progress. I used to tell a pathetic joke in China that perhaps explains it: I had learned Chinese in SOAS, self-reliance in the army, how to do business through metal trading. So all I had to do was learn to read and write in English and I could publish a magazine in China.

Chinese Boxing will run for one night, March 15, 2022, at the Headgate Theater, Colchester, and has been “heavily penciled” for March 10 to 12 at the Playground Theater in London. More venues to be confirmed in 2022.