Explaining China’s relationship with Indonesia, its gateway to Southeast Asia

Whether it’s trade, the Belt and Road Initiative, venture capital, or vaccine diplomacy, Indonesia — traditionally a major U.S. democratic partner in the Indo-Pacific — has increasingly embraced China.

In December 2019, three Chinese coast guard vessels escorted 63 Chinese fishing boats through Indonesia’s territorial waters in the South China Sea. Jakarta responded by dispatching five warships and four F-16 fighter aircraft. For two weeks, a tense standoff ensued. Some observers hailed the moment as an opportunity for Jakarta to lean closer to Washington; others predicted the rise of a united ASEAN against China’s coercive behavior in the contested waters.

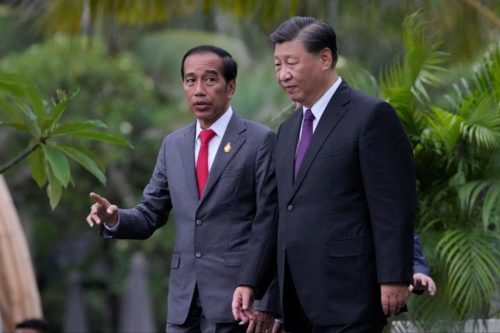

Nearly two years later, the flare-up looks like a distant memory. And U.S. officials like former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, who spoke of “new ways” to cooperate with Indonesia against China, now seem like they were being wishful. This April, Indonesian president Joko Widodo told Chinese president Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 that China was a “good friend and brother.” China-Indonesia cooperation on trade, industrial parks along the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and venture capital have since flourished. China has also donated more than 200 million doses of COVID-19 vaccines. Indonesia’s improving relations with China, which could significantly challenge America’s leadership in the Indo-Pacific, offers an important lesson for U.S. foreign policy: Other countries don’t want to just be used to counter China.

One reason for Indonesia’s dramatic reversal might lie in the Donald Trump administration’s transactional and “America First” foreign policy, which sidelined U.S.-Indonesia relations. From Jakarta’s vantage point, it was not relevant to Washington until Pompeo publicly sought to resist China’s maritime claims in the South China Sea in October 2020. Yet Pompeo’s proposal to Indonesia violated Indonesia’s longstanding policy of nonalignment in the U.S.-China contest. As Indonesia’s Minister for Foreign Affairs Retno Marsudi previously told Reuters, “We don’t want to get trapped by this rivalry.”

Beijing, on the other hand, has consistently engaged with Jakarta — not just when an opportunity to gain an edge in “great-power competition” with Washington appears. By 2030, Southeast Asia is projected to become the world’s fourth-largest economic bloc. China has rightly identified Indonesia, with its rising economy and expanding tech sector, as a crucial gateway to expand into the burgeoning Southeast Asian market.

Beijing has been Jakarta’s largest trading partner since 2013. In 2020, China was Indonesia’s top export destination, accounting for more than 16% of the nation’s total exports. That year, the total value of Indonesia’s trade with China topped $78.5 billion. In 2019, both countries signed a local currency settlement agreement that will expand the use of the Chinese yuan in Indonesia, which took effect in September.

China views Indonesia as a crucial BRI partner. After all, it was during an October 2013 speech in Jakarta that Xi first unveiled the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. While ample coverage of the BRI in Indonesia has focused on the setbacks of the $6 billion Jakarta-Bandung railway, such analysis often fails to acknowledge the progress of other Chinese-funded projects. Chinese companies have invested at least $12.7 billion into Indonesian steel and nickel projects since 2013. Three industrial parks in Weda Bay, Morowali, and Qingshan paint a different picture, highlighting extensive China-Indonesia cooperation. Weda Bay Industrial Park’s ongoing projects, including a plant to produce nickel sulphate and a $2.8 million copper smelter, involve partnerships between multinational firms and the Zhejiang-based Tsingshan Holding Group. At Morowali Industrial Park, a collaboration between Tsingshan and Indonesia’s Bintang Delapan Group, plans are underway to build a $350 million lithium chemical plant. And Chinese state banks have bankrolled Qingshan Industrial Park, a joint venture between Shanghai Dingxin Group and Indonesia Eight Star Group that has employed more than 35,000 Indonesian workers since 2019.

Private Chinese firms have also leapt into the Indonesian investment frenzy. Many Chinese investors view Jakarta as a crucial hub for expanding into the rest of the region. One Chinese venture capitalist joked, “When [Chinese] investors talk about ‘Southeast Asia,’ they are referring to Indonesia.” Today, Indonesia boasts the largest number of billion-dollar start-ups in southeast Asia — a distinction propelled in no small part by massive inflows of Chinese investment. In May, Indonesia’s ride-hailing and payments firm Gojek merged with ecommerce leader Tokopedia to create the new tech conglomerate, GoTo, in Indonesia’s largest-ever deal, worth an estimated $28.5 billion. Two of GoTo’s biggest investors are Chinese tech giants Alibaba Group and Tencent Holdings. Shunwei Capital, launched by the founders of mobile phone maker Xiaomi, and BAce Capital, backed by fintech giant Ant Group, plan to sign more deals in Indonesia. Such investments seem likely to continue: In April, Xi told Widodo that his government would support the efforts of Chinese domestic firms to boost investment in Indonesia.

China-Indonesia relations have further improved because of Beijing’s “vaccine diplomacy.” More than 80 percent of the vaccines Indonesia has received from abroad has been from Chinese producers, as of late September. While some Western media outlets have described rising doubts within Indonesia about the efficacy of China’s vaccines, Jakarta’s actions indicate otherwise: The government has cleared a COVID-19 vaccine produced by China’s Chongqing Zhifei Biological Products for emergency use, the fourth Chinese vaccine approved in the country. Partly as a result, China has won support from the Southeast Asian nation on certain core political issues: In October, Indonesian foreign minister Marsudi joined Chinese State Councilor Wáng Yì 王毅 in “voicing serious concerns” about the trilateral AUKUS security pact between the U.S., UK, and Australia.

Washington has responded to recent developments in China-Indonesia relations by striving to revive its strategic partnership with Jakarta. In August, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken launched a new “strategic dialogue” with Indonesia to discuss South China Sea defense. That month, both countries initiated their largest ever joint military training exercises, which involved 3,000 troops. America has also donated 8 million vaccine doses and provided more than $65 million in coronavirus-related assistance. But Indonesia seems wary of drawing too close to Washington, which showed itself to be an unreliable partner under Trump and was arguably “snubbed” by high-level Biden officials in their recent visits to Southeast Asia.

While wary of the nation’s human rights abuses and past purchases of Russian weapons, the Biden administration has also sought to strengthen ties with Indonesia, recognizing Jakarta’s outsize geostrategic importance in the Indo-Pacific. The U.S. State Department has shown interest in selling armed MQ-1C Gray Eagle drones to Indonesia. And on the sidelines of the recent U.N. Climate Conference in Glasgow, Biden spoke with Widodo about “ways to strengthen” the bilateral relationship.

Indonesia is unlikely to join any sort of U.S.-led coalition against China. The challenge before the Biden administration is to convince Jakarta that a closer relationship with Washington is in the best interest of an independent and sovereign Indonesia. The Southeast Asian state does not want to be relegated to yet another pawn on the chessboard of the U.S.-China game. Until then, Indonesia will mostly side with Beijing, skeptical of America’s intentions and its foreign policy defined by strategic competition with China.