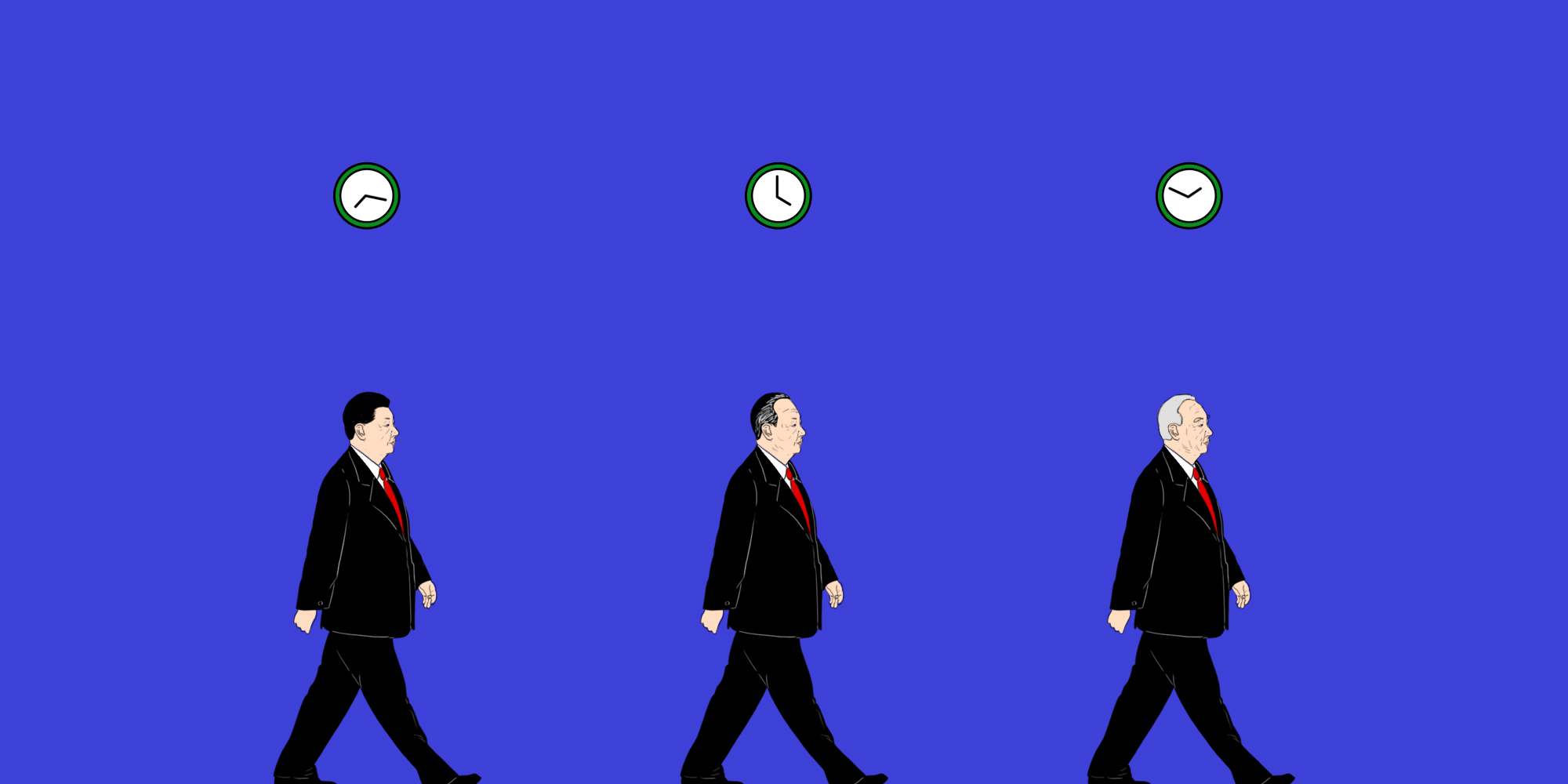

What role will age limits play at China’s 2022 party congress?

Experts weigh the possibility of the weaponization of retirement norms among top leadership positions at the Chinese Communist Party’s key meeting next year.

With the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) Sixth Plenum of its 19th Central Committee in the rearview mirror, observers are gearing up for next year’s 20th National Congress — a pivotal meeting which will determine China’s leadership from late 2022 through 2027. Some officials will be promoted into coveted positions, others will be sidelined, and still others will be pushed into retirement after hitting age limits instituted by the party.

Since 2002, the CCP has remained largely consistent in enforcing rules for age limits on party posts. Internal party rules dictate that governors and party secretaries of any given province, as well as ministers in China’s cabinet, must retire at 65. Exceptions, however, can be made for those provincial officials who have seats within the party’s Politburo, the powerful policy-making body made up of China’s 25 top officials. For officials with positions in the Politburo and the larger Central Committee, an age cap of 68 has been upheld at recent party congresses. In China this is referred to as the qīshàngbāxià 七上八下, or “seven up, eight down” norm.

Many expected the 68-year-old age cap for central leaders to be set aside at the 19th National Congress in 2017 in order to allow Wáng Qíshān 王岐山, then the head of China’s top anti-corruption body and a close ally of Chinese President Xí Jìnpíng 习近平, to remain in the Politburo. In fact, age limit norms were upheld; Wang retired from his party position and assumed the role of vice president, a largely ceremonial position.

But at the next party congress, at least one person will be exempt from this rule: President Xi himself, who is currently 68. In 2018, Xi formally abolished term limits for president written into China’s constitution, so it’s unlikely he’ll let a rule on age caps usher him off stage.

Victor Shih, an associate professor of political economy at the University of California San Diego and expert in Chinese elite politics, told The China Project there was virtually no possibility of Xi stepping down from any of his leadership positions (president, General Secretary of the CCP, and Chairman of the Central Military Commission). “If he were to do that, he would have ceded the chairmanship of at least one of the leading groups to someone else,” Shih said, referring to ad-hoc bodies tasked with addressing specific issues of national importance. “He’s still the chairman of the leading group for nearly everything.”

But what will happen to China’s other old political leaders? Will Xi’s override of age caps for himself be extended to officials aligned with him?

Eleven members of the Politburo (not including Xi) will have reached retirement age by the party congress next autumn, including two members of the party’s top policy-making body, the seven-member Politburo Standing Committee: Hán Zhèng 韩正 (currently 67) and Lì Zhànshū 栗战书 (71). Han and Li are closely aligned with Xi; Li worked in a locality near Xi in Hebei Province in the 1980s and Han worked under Xi when the latter was Party Secretary of Shanghai.

Some sharp-eyed observers have noted recent examples of party leaders observing age-limit rules for some officials while ignoring them for others — suggesting that these norms may increasingly be used when politically convenient, and spurned when not. Citing as evidence several provincial-level officials who are aligned with Xi and who have retained their party roles despite reaching retirement age, Guoguang Wu, professor of political science at Victoria University, has argued that in recent years the retirement of leading officials has become an instrument for Xi to control personnel appointments. Wu predicts that “as the retirement of leading cadres becomes politically selective, forced retirements can be used by Xi as a convenient tool to overcome any difficulties to actualize his political purges.”

Radio Free Asia columnist Gao Xin more recently made a similar case, pointing to Ruǎn Chéngfā 阮成发, who recently retired from his post as Party Secretary of Yunnan Province due to his reaching the 65-year age limit. Gao notes that other officials even older than Ruan, such as Hubei Party Secretary Yīng Yǒng 应勇 (celebrated in the party for his strong handling of the pandemic in the province where it originated), Sichuan Party Secretary Péng Qīnghuá 彭清华, and Ningxia Party Secretary Chén Rùn’ér 陈润儿 have all retained their seats, despite being at or near retirement age. Gao’s analysis suggests that Ruan was likely sidelined for political reasons, while Ying, Peng, and Chen may still have hopes for heightened status in the party, even promotion into the Politburo.

But other experts caution against viewing such recent developments as indicating Xi’s plans. To jettison age caps could actually threaten Xi’s grip on power in certain ways.

“In theory, it’s advantageous for him to stick to the retirement rules for everyone else except for himself, because then it prevents the other people from building up a power base,” Shih said. Getting rid of the rules around retirement ages could be destabilizing for the party, Shih added. “If these people don’t retire, then people can’t move up, and that will change the incentives in the entire system quite a bit.”

He also downplayed the recent trend of provincial-level officials staying in their positions past retirement age. “For the promotion between the Central Committee into the Politburo, that’s always been the case,” Shih said. “As some of these people reach the age of 65, they should really retire, but not if they get a promotion into the Politburo that allows them to serve into their early 70s.”

Some commentators, such as China Strategies Group CEO Chris Johnson, have also floated the possibility of Xi Jinping taking a page out of Máo Zédōng’s 毛泽东 playbook from 1969’s Ninth National Congress, when Mao pushed huge numbers of officials out of top positions, resulting in over 80% turnover in the Central Committee.

“I don’t think you get rid of age limits at the Politburo level because they’re so fundamentally useful for keeping the rest of the party and country in check everywhere else,” said Tristan Kenderdine, research director at Future Risk, a consultancy focused on political risk and economic geography. “The ability to shape who comes up and repress who’s not coming through is just so useful, even though there would be short-term gains at the Politburo level to circumvent the system [of age limits].”

Ultimately, whether or not Xi Jinping chooses to eliminate age limits for his allies will have significant implications for the system as a whole. If Xi’s over-age allies don’t retire in 2022, not only will it indicate a political environment in which Xi has virtually no checks on his authority, it will also point to a further erosion of institutions in the CCP.