The China story behind Apple’s $3 trillion valuation with Doug Guthrie

From 2014 to 2019, Doug Guthrie led Apple University’s efforts on leadership and organizational development in China. He speaks to Chris about how Apple’s current success is due in large measure to the deep partnerships the company has in China.

Below is a complete transcript of the China Corner Office Podcast with Douglas Guthrie:

Chris: Hi everyone, thanks for joining us today on China Corner Office, a podcast powered by The China Project, the New York-based news and information platform that helps the West read China between the lines. I’m Chris Marquis, a professor at the Cambridge university Judge school of business. And today’s episode features a discussion with Doug Guthrie, who from 2014 to 2019 led Apple University’s efforts on leadership and organizational development in China.

Over 25 years ago, Doug landed in China and spent a year biking around Shanghai, interviewing factory managers, and he published the results as an award-winning doctoral dissertation. Since then, he has had deep engagement with the country on both academic and practical levels. He was a professor in places like NYU and Harvard Business School and served as Dean of George Washington School of Business. Following his time at Apple, he became a professor and the director of China Initiatives at the Thunderbird School of Global Management at Arizona State City.

Apple recently became the first company ever to reach a $3 trillion market capitalization, and as we discuss, Apple’s current success is significantly due to the deep partnerships the company has in China. A very visible part of this, of course, is the impressive sales of iPhones and other products to Chinese consumers. In the last five years, about 20% of Apple sales have been in China. But as Doug emphasizes, an even bigger factor for the company success globally is the concentration of Apple supply chain in China. This leads to incredible profitability for the company, but also gives the Chinese government significant leverage.

Doug describes how many companies, such as Apple and Tesla, who’s been in the news recently about opening a showroom in Xinjiang, are essentially married to China. Doug provides a number of illustrations of how the rule of law system that are used to in the west is very different than the rule by law system that exists in China and how the government can use policies like the cybersecurity law and labor dispatch law to extract compromises from companies.

At the end of the podcast, we also discuss Doug’s pioneering dissertation work in 1994 in Shanghai, and how from that point forward, he has been firmly convinced that it is language skills and cultural knowledge that are the essential tools for businesses interested in working in China and with Chinese companies. Thanks so much for listening and enjoy the show. Doug, welcome to China Corner Office.

Doug: Thank you for having me, Chris. I’m so happy to be here.

Chris: Yeah. Really looking forward to diving in and understanding more about Apple, your perspectives on US-China relations more generally. Where I’d like to start actually is in regard to Apple stores in China. I’ve been to so many different US and global retail outlets in China, and it seems that Apple really does the best of bringing its international presence to China in a way that is standardized really effectively. A lot of the discussion we have on China Corner Office is about how companies localize, but it seems that Apple is really able to standardize its processes, training, et cetera, and I know that you as the head of Apple University in China, probably played a role in that. So I’d love to just start with that.

Doug: Chris, so great to be here and so great to be talking to you. A couple of key things just to think about, Apple has done an amazing job at rolling out their theory of customer support and customer engagement. They very much want it in the company to have this standardized view of what an Apple store looks like. And building that in China, I think was a fascinating thing. Now, I was a leadership development trainer. So I wasn’t an architect of what they were doing. There were many other people who were doing those things, but we were also always was trying to train about Apple culture.

And I think the executives of Apple did an amazing job at thinking about, how do you move this culture from what it looks like in the United States to what it looks like in China or anywhere else in the world. Now, one key part of that, which I think is behind your question is, they also cared about Apple culture. And so there was a time when I was brought over there to really be thinking about Apple culture and how do we train executives and young executives and senior executives, but just executives that think about the culture of the company and they did an amazing job at it.

Chris: Is there something like maybe, I don’t know, examples or details that you could provide to understand? I mean, it’s really hard to train culture in a classroom standup way, were there people coming to the US and experiencing what Apple’s like? I’d just love to get a good feel for what that actually means.

Doug: So let me handle this in three or four levels. So the first thing is, just remember, Chris, you and I have known each other a long time and we’ve been a part of the executive education world, like we’ve known about corporations that build institutions like Crotonville [GE’s global leadership institute] and sometime around 2008, 2009, I don’t know exactly what the dates were, but Steve Jobs decided that he needed an Apple university, he needed something that was really going to help people understand the culture.

And so he went out and recruited one of the great thinkers in this world, who you and I both know, Joel Podolny, who was the dean of the Yale school of management and they built Apple University. But the interesting thing about Apple University is that they weren’t built around training, about business skills, they were built around culture. How do we build a company culture? As I understand what Joel’s role was, it was to build that, and he did, and Apple University became a thing and it became a thing that we all were engaged in. And then when I left my deanship and was recruited by Joel, we tried to build that, not just for the US but also for China.

So there was an interesting moment, and this is the second phase of the answer to your question, Chris, is there was an interesting moment when I was hired to go be the lead for Apple University in China, there were six Apple stores.

Chris: Wow

Doug: Right. When I left there were 52. That’s not because of me-

Chris: But you played a role in the rollout of it.

Doug: Well, I played a role in helping train the people and it was interesting. There was a moment when I was in negotiation with Apple, I wasn’t sure what was going to happen, and Tim Cook was in a comms meeting at an Apple store and it was in the Apple store in Beijing. There was somebody who asked a question, which was, I thought, a brilliant question. They were like, “How are you going to maintain the Apple culture and continue to go forward in rolling out all these stores with your plan?” And Tim said, “Well, we just hired this guy, and it’s still in negotiations, but at some point he’s going to be here and we’re going to be on the ground in China.” And it was funny because I didn’t know that I was hired yet.

And so, it was just like an amazing moment, because I got calls from people like, “Is that you?” But that was Tim Cook’s and Joel Podolny’s vision. Like if we’re going to do this, we got to have somebody on the ground who both understands China and understands what it is that we need to do with the merging of China and Apple culture. And that became my job. Now again, Apple stores, they started rolling those out very fast and by the time I left, I think they were 52 stores and they’re all amazing. My job was to help people understand Apple culture and organizational culture.

Chris: Got it. So, what insights do you have then on … I mean, my experience in a variety of different Chinese cities is that, after you get away from the East Coast actually, English and actually like Western ideas of customer service fall off pretty quickly. I’d love to hear about any experience that you’ve had in an interior location, they’re starting an Apple store, were there any special challenges, what’s actually done to actually get the staff up to speed on the standards that Apple thinks are appropriate?

Doug: So, let me answer the question in two ways. So the first is that, when I arrived for Apple in China, I was very, very focused on what the political issues were. And it seemed clear that the new administration in China was going to be thinking more deeply about what US-China relations and what multinational relations were in China. And so that was my first project, I was trying to figure out like, “Okay, how do we help everybody understand this?”

And then there was some point, Chris, when I feel like the executives at Apple said, “Okay, Doug, we got it. We understand, and government relation has this, we got it.” But then there was a second-tier version of the issue, which is, but we’re very good in tier-1 cities, I assume most of our listeners probably know this, but just to reiterate, Chinese cities are divided into tiers, tier-1, tier-2, tier-4, tier-5, all the way down to tier-6 cities.

And I got the message from some executives that we don’t really understand, what you framed Chris as, the “west” or “the hinterlands.” Like we don’t understand these. And so our second project that we did and I worked very closely with an Apple executive who was based in Shanghai, and he’s a creative director kind of person. And we just went out and we just started interviewing people and just started talking to people about like, “How do we understand what’s happening in the hinterlands?” Because all of those people were using Xiaomi, Oppo, Vivo.

Chris: Huawei.

Doug: Right Huawei phones. Why not Apple? And it was because we weren’t there. And so it was a really interesting project for me, because I’m not a creative director, brand strategy is not my thing, but it was so interesting to just do economic analysis and just go deep and go interview people. It was one of the best projects I’ve ever done in my life because it really got me deep into … I was like sitting next to a basket maker who was having his baskets on Taobao and it was trying to help Apple executives understand what this means like. It was incredible.

Chris: Yeah. Real interesting. So, part of what you mentioned is that just Apple was not there. So, opening up a flashy glass, beautiful Apple store in the most high profile mall obviously says something, but like for this basket maker or any of the other folks you interviewed, I mean, was there any sense of nationalism like there is today or any sense of like what maybe the price of the product, I mean, I’m curious with those people sitting in Taobao are thinking as they’re choosing a cell phone and why Apple versus Huawei, for example?

Doug: Right. Again, there’s price differential in these areas. But the important thing that I wanted Apple executives to understand is that, yeah you can be in tier-1 cities, Shanghai, Beijing, Tianjin, Xinjiang, we all know those. But that is a small portion of the population. Like this is a population of 1.4 billion people. And most of the economic development is happening in tier-2, 3, 4 cities. So, for me, I really wanted to help executives at Apple understand like, “We need to go deep, we need to go deeper.”

There’s a lot of smart people there, so I can’t take credit for having pushed them in those directions, but again, they expanded from when I joined Apple, there were six stores and then there were 52 stores when I left. They clearly were thinking about these issues. And even if the margins of what you can get in tier-3, four cities, still the population’s huge.

Chris: Right. Yeah, I can see that. Really, really interesting. Is there anything that stood out as far as, was there, I guess, delivery or training of the personnel different in those locations? Or was it still the same as one would get in, I don’t know, Palo Alto or Shanghai, or, name your tier-3 city, I assume tier-2 like Chengdu and Wuhan. I mean, those are more sophisticated. I mean, really there’s probably even a bigger drop-off when you get down to the tier-3, tier-4.

Doug:

So it’s a good question, Chris, but of course the training was different in China than in Cupertino. And that was what I tried to do, I wanted to really customize this for China, and really think about like what … And you have to know, most of my students when I was in that role were Chinese people. And so they needed to know that there was somebody who understood China and thought about China and could rip out a Chinese phrase that was a chéngyǔ 成語. So it was definitely different, but we tried to customize it for China.

And we also tried to customize it for China around the strategic issues that the company was thinking about. Again, just to go back to what we were just talking about, one of the best projects we did was a project we did for marketing. We went out into the hinterlands and just interviewed the basket maker and also a woman who was the head of a company that was trying to compete with Nike. I mean, we just tried to find these people. And so we tried to customize it for China, and I think that’s credit to Apple, they tried to do that.

Chris: Yeah, really interesting because my experience and I think I’ve only … I might have been in Chengdu in an Apple store, I can’t remember, but the work may be customized to the actual individuals you’re training, but actually it is the delivery, at least to someone with a white face like me that walks in is pretty seamless to what I’d experience elsewhere. So I think that says a lot about the work that you guys had done.

I want to ask, so actually in the last few days, Apple has gone over 3 trillion in valuation. I mean, the first company to ever do this. And I think a big reason is China, and we’ve talked about this consumer success, and I think about 20% of Apple sales over the past number of years has been to China. But another big part is the supply chain component and the manufacturing component. I’d love to hear just maybe start very broadly, maybe with an open-ended question as to, can you just reflect on sort of, in some ways, the power of Apple’s supply chain in China?

Doug: Yeah. So Chris, it’s a great question, and I just want to be very clear on this, and here I’m going a little bit off the grid because I can’t speak as an Apple executive anymore, but I will just say yes, Apple has this significant market in China as does Tesla and other companies. But the thing that makes these companies so powerful is their management of the supply chain. I mean this is the thing, because companies like Apple and I know less about Tesla, but I’ll just extrapolate, but companies like Apple and Tesla, they do a very good job of embedding people in the supply chain and helping the suppliers actually understand the technologies and the supply chain management that they’re doing. Right?

And what happens then is just with any company, whether it’s electronics or automobiles, you have components, modules, and final assembly. Right? Most people think like, “Oh, Tesla, they have a factory in China. Its final assembly.” No, actually it’s components, modules, final assembly. And in every one of those levels, the companies that are the most innovative are helping to teach the suppliers how to run their supply chains, and they always teach multiple suppliers. And so what happens is that the suppliers become competitors against each other.

And so I can just tell you, I’ve had multiple meetings with CEOs of suppliers of Apple, and they would say, “Why are we pushed to such slow margins?” And I’m like, “Well, you’re paying for it because you want access to the expertise and that’s what everybody wants.” Here’s my favorite statistic about Apple in China. So Apple controls about 35% of the smartphone market share in the world, but they take about 95% of the profit.

And why does that happen? It happens because they’re able to leverage their expertise to push suppliers to do what they want them to do. And then those suppliers go make their money from Xiaomi, Oppo, Vivo, everybody. Again, I know less about the electric vehicle world, but I guarantee you it’s the same thing. I mean, Tesla got a very special deal. Right? When they were the first auto company that was allowed to come in as a non-joint venture, and I guarantee you, there were promises made.

Chris: Yeah, no, interesting. I’d like to talk a little bit about those promises in a second, but first I want to ask about this, it seems like there’s a lot in some ways IP sharing going on. So, these engineers are entering these factories and learning about, I mean, that’s why they’re willing to accept these very low margins because that’s actually their learning, and then like you said, they can go and use these processes for Xiaomi or Oppo, whoever.

The reason I’m going to ask this question is, I’ve actually heard Elon Musk be asked like, “Aren’t you worried that the Chinese are going to steal your IP?” And I think he said that, “Well, if they’re stealing the IP, that’s actually what’s going on now, but actually what’s going on tomorrow is what we know back in the US, and so it doesn’t really matter if they’re actually stealing our current IP because if that’s already by definition old.” Is that the philosophy that Apple had, that doesn’t matter if they’re able to actually …if these competitors get their IP because the next generation they’re going to be doing this all over again?

Doug: Well, Chris, I think it’s a great question, but it’s a complex question. Just to dial back a little bit historically, personally, I get a little upset when people talk about China stealing IP, because as you know, I mean, you’re a China scholar too, China developed a lot of the great IP that transformed the world.

Chris: Totally. Yeah.

Doug: Gun powder, the nautical compass, paper money. This stuff changed the world in the 1400s. And so the idea that the world is not a global political economy just seems strange to me. Now, in today’s era, when we talk about companies like Apple and Tesla, I have a difficult sense of thinking about just this pure IP, because nobody’s like giving away the IP of chip manufacturing or the IP of … But the real IP is around manufacturing processes. And that’s what, in my view, Apple has offered to China, and it’s amazing.

I mean, Apple will never set up a factory in China. What they did was they took their employees who are brilliant people in operation supply chain management, and they embed them in the factories of China’s suppliers. They teach and everybody learns together. And so it’s hard for me to think about this as some commentators think about this as stealing IP — I don’t think it’s stealing IP. These are collaborative relationships in which people learn together.

And yeah, it is the case that manufacturers and product-oriented people like Apple, and I assume it’s the case with Tesla, yeah, they teach their suppliers how to do great work, but that’s because China has the most ingenious manufacturing supply chain system in the world right now, and we all need each other.

Chris: Yeah. Interesting. Yeah, I appreciate that. I think that’s probably a fair way to actually think about their relationship. So thank you for that. In regard to the … You mentioned China has this amazing supply chain ecosystem and infrastructure, do you think that companies like Apple and Tesla are then maybe too tied to China? It’s not like they can move their production elsewhere. I mean, you mentioned it’s about the components and modules and going down the supply chain, a variety of integration that’s happening, where you really can’t replicate that. But then that gives China and Chinese companies and the Chinese government really a lot of leverage.

Doug: Well, it’s a great question, Chris, and I think that there are three levels to the complexity of that relationship. I just think China has tremendous leverage. The first level, now I’ve heard leaders from Congress and the former president talk about like, “Well, companies like Apple should just move to Vietnam or move to India, it’ll all be fine.” But we don’t have the leverage that we think we do for these three reasons. First, is the floating population. There are 350 million people that are what we call “float” around the country, but they’re actually moved by the government. This batch labor system is a tremendously powerful system in which the government moves people. The Chinese government moves people around the country to be at whatever factory needs them for seasonal production. This is amazing. It’s an amazing system.

And so, just having 350 million people, when people talk about like, “Well, we should just move our production to Vietnam.” Okay. There are 95 million people that live in Vietnam. The entire country couldn’t support what it is that is the production that’s happening in China. And there’s not a system for moving people around. The second thing is infrastructure that ties the system together. When people talk about, “Well, we should just move all our production to India.” India doesn’t have the infrastructure that links the states of India together the way China has developed.

China’s system of linking suppliers to final assembly factories, there’s nothing like it in the world. And then the third piece is what I like to refer to as industrial clusters. So many different cities in China have developed their entire system around focus on a very specific component or module. It’s just a system that has been developed in industrial development for the localities of China that I just think have made a dramatic difference. When you put those three things together, you can’t replicate this anywhere in the world. So it’s hard for me to imagine that a company like Apple or Tesla could leave China.

Chris: Interesting.

Doug: I don’t see it.

Chris: I’d love to learn a little bit more about the labor dispatch system you mentioned. I mean, the infrastructure, the clustering, I think is written about a decent amount and I’m a little … I think the listeners will be somewhat aware of that, but this labor dispatch system you mentioned where the government is actually involved in moving the floating population, as I would think about it, I know Foxconn in some location, Apple has a new phone coming out, they need to ramp up production, so they put advertisements, who knows where the migrant labor is looking for advertisement? Would be my way of thinking that they may do it, but I guess, you’re saying the government is more deeply involved in this than I may realize.

Doug: So thank you for that, and it’s a great question, Chris. So the labor dispatch system is a system that is tied to moving migrant labor around the country. Right? So think of it, I mean, for our American listeners, think of it as a temp labor company. Right? So temp labor are these companies that basically take people who are not employed somewhere, and then they just say like, “Oh, go work for this company for a few days or this company.” So the labor dispatch system’s like that, it’s basically a system in which you take 350 million people and you figure out which companies because of surges in production are needing laborers, and we’re going to move them around to these places. Right?

So, just to give you, you mentioned Foxconn Zhengzhou. So, Foxconn Zhengzhou is one of the main final assembly plants for Apple products, and I can’t quote very clear numbers, but in my memory, if you were just at steady state, there would be 200,000 people working on iPhone products or Apple products, but every year around September, there’s a new iPhone release, and suddenly you need 500,000 people. Right? So who’s going to get those people there? That’s the dispatch labor system. The dispatch labor system moves people, and it moves people around the country, and it’s a very interesting system because it’s a state-run system. And so people are actually moved around the country and they are actually employed by the dispatch labor system.

Now, one of the things that has made it hard for foreign companies is that they’ve changed laws. So the dispatch labor law, which I think came out in 2015, it made it harder. Then companies have to figure out like, “Okay, what are we seeing based on the rule by law system? There’s a new dispatch labor law, what does that mean for us? What do we need to negotiate with the Chinese government to do that?” That’s what the rule by law system means. And so the dispatch labor law and the cyber security law, they’re the two biggest laws that have really changed what companies like Apple and Tesla have to do in the world.

Chris: Yeah. In regard to that, that’s actually nice foreshadowing. I appreciate, that’s actually where I was going. Next is in regard to this leverage that we have talked about, the Chinese system, in some ways the government CCP, the companies have over US companies and international companies that want to actually produce materials there. The cyber security law is something that’s in the news a little bit more in the Western news a little bit more about Tesla recently, I think there were some reports about them, with data security and having all the data that’s from China reside in China.

I think there was some stuff reported recently on Apple too, and the fact that they’re maybe the encryption keys also are relying on China. Can you say more about those laws and what kind of leverage in some ways they then give the Chinese government over producers like Tesla, for instance, or Apple?

Doug: Yeah. I can’t speak too specifically about some details, but let me just speak generally to your question. So when things like the dispatch labor law come out, so the dispatch labor law — again, I can’t remember the exact year, but it may be 2015 — but it completely changed the ways in which dispatch labor was going to be used in China because a lot of suppliers of foreign companies were using about 50% dispatch labor, and suddenly the dispatch labor law comes out and it says, “You’re only allowed to use 10% dispatch labor.”

Now, this makes the situation economically inviable because dispatch labor is cheaper, it’s seasonal. You have all of these things that flow into like why it’s such a beneficial system. Now, I had a number of conversations around that time with lawyers who were saying, “How can we comply with this? We can’t.” And my answer to them was generally, “That’s not the point, you’re not supposed to comply.” This is what’s called the … In the west, we live by what we call a rule of law system in which you have governments that create laws, and then you have independent judiciaries, and then you have companies and the independent judiciaries adjudicate those laws.

In China, a rule by law system is not that, a rule by law system means you’re supposed to be out of compliance. That’s the point. And when I would talk to lawyers about this, people would say like, “What does that mean?” And the answer would be, “Well, you’re out of compliance, but you need to go figure out what the mayor of Zhengzhou wants from you.” So this is China’s post-WTO entry. So China’s now part of the WTO and there are certain rules, but they can create laws that make it very difficult for foreign companies to navigate. And then you need to go figure out what favors you need to do. That’s the system, same for cybersecurity. Cybersecurity law created a lot of difficulties for a lot of companies that were dealing with content in China. Again, the answer was, “You need to figure out what you need to do.”

Chris: Got it. So under WTO, they can’t ask for certain things, but if you go to-

Doug: Correct.

Chris: With the legal system the way it is, they have this leverage where, I guess, Foxconn in Zhengzhou can go to whomever Zhengzhou party secretary or mayor, and work out a deal, and that’s one way, in some ways, actually they get around this dispatch labor law, but then also subvert the WTO in a way that actually explicitly does not subvert it, but in spirit it does.

Doug: Correct. I mean, officially by the WTO rules, you can’t have a quid pro quo for market access, but if you have laws like the dispatch labor law, or the cybersecurity law that make it very difficult for foreign companies to operate, they’ll have to figure out what they want you to do.

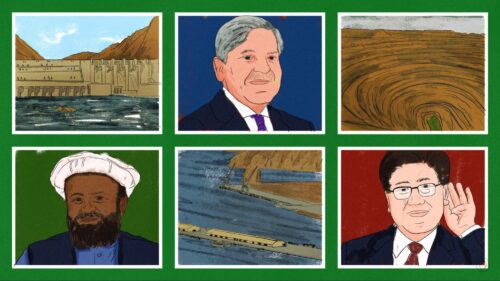

Chris: Another somewhat controversial area, and this is in the news just today, Tesla, it was announced they’ve opened up a facility in Urumqi in Xinjiang, and I know that Apple has had some, at least the media reported work in Xinjiang that is controversial. What’s your sense about maybe speculate about Tesla, why is Tesla doing this given we know how controversial this is in the world today?

Doug: Yeah. Here again I can’t talk specifically about Apple’s decisions with respect to Xinjiang because I just haven’t been there. And so I’m just a reader in the news, but I think the interesting situation with companies like Apple and Tesla is that they’re married to China. Like they cannot be without China. And again, it’s not just, a lot of people think whenever I talk to executives about this, they think it’s because of the market. It’s not because of the market, it’s because of the supply chain. These companies are so dependent on China because of the complexity of the supply chain in the ways that we just discussed.

I can only speculate, but I guess like they have to be present. And so, when I read the news that you’re just talking about with respect to Tesla in Xinjiang, I don’t know, I can only guess that there’s a very clear pressure that they need to be with the Chinese government and they need to make it clear. So, I don’t have any deeper insight into Tesla than that, but that’s my guess.

Chris: Got it. How about, I’m curious, political economy more generally? I know when I talked to you back in 2014, maybe even earlier, I mean, you were one of the early people that was raising alarms about the way that China may be led under President Xi, with things that have become much more clear in the last few years, I think to a more widespread set of observers. Can you maybe comment a little bit on what were some of the early things that gave you pause about Xi, and any thoughts about where you think things are headed given the last few years really of all this crackdown on a widespread set of industries crackdown on wealthy people, focus on common prosperity, et cetera?

Doug: Okay. Yeah. Couple of key things, for those of us who were China watchers, we were watching what was happening in the transition from Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao to Xi Jinping. And I don’t think we were so clear on how … Everybody, I think thought, many people thought that there was going to be a stronger authoritarian hand. I don’t think we ever predicted what was going to happen, but the thing in piecing it together now and looking at hindsight, I do think it’s important to remember there were two moments that occurred during this period.

The first was that Xi Jinping was a very ambitious leader and it was very clear that he wanted to take China to the next level. Right? So it’s not a coincidence that the Belt and Road Initiative, even though there were talks about the Belt and Road Initiative in 2008, it was really officially launched under Xi Jinping. And what is the Belt and Road Initiative? The Belt and Road Initiative is really about China’s pivot away from the west.

We are not going to be dependent on US-China relations. We’re going to be the largest economy in the world and the leader of what they call in Chinese nánnánhézuò 南南合作 which means “South-South relations.” We are going to lead the South China Sea and Africa and the Middle East and China is going to be the centerpoint of this. So, in some ways it was like an economic decision, but it’s dramatic in that moment. And so when I was watching that, I started to really have a deep sense, Chris, of like, “There’s something going on here that’s bigger than we know.”

The other thing that I think is really important is, I do think that the second moment like Donald Trump being elected in 2016, and our country has been damaging to this relationship, the fact that Peter Navarro was the main negotiator for US-China trade. I mean, this is a guy who wrote a book called Death by China. I mean, just think about it. China also is rising in its sense of nationalism, not just in the government, but also among the populace. And so like the idea that you have somebody who wrote a book called Death by China coming over to negotiate trade, I just think it was damaging for everybody.

And so I think those two things like you have the rise of Xi Jinping and then you have Donald Trump. And so I think it’s been a really, really hard time. I’m hopeful. I was more hopeful with the Biden administration that we’d be more back to engagement, but Kurt Campbell doesn’t seem to talk about engagement. He seems to talk about competition. I just think we’re in the midst of all of this. Now, to go back to our earlier conversation, I actually think companies like Tesla and Apple are going to play a critical role here. We don’t know what role they’re going to play yet, but I just don’t think we can quit China. I just think another Cold War is going to be painful for everybody. So, we’ll see.

Chris: Yeah, it does seem, I mean, there’s such deep economic connections, both ways. I mean, I think we’ve talked about mainly these US companies that are really dependent on the China supply chain, but also deep China ties in the US too. I’m with you. I do hope that we’re able to work out something, and I do think companies play a really important role in this. Given some of the things that we’ve mentioned though about this dependency, things like maybe sharing data, other issues about maybe being implicitly forced to support Xinjiang policy, what’s your recommendation for companies that want to do business in China? Is it, go into this with eyes wide open, where do you draw the line on where to compromise basically?

Doug: It’s a great question, and I’ll give you two quick answers. This is typically when I say to CEOs that want to get my advice. The first is that you have to think about partnership in China. And I believe in partnership, not just with Beijing, but with localities. This is I think a mistake. Again, I have not been involved and have not heard from Elon Musk. He doesn’t have my phone number, and so, it’s not like I’ve been advising him, but the big moment things are important, but the most important thing in China is local connections.

Again, think about, Chris, you and I just talked about, yeah, we all know the first-tier cities, but what are the second and third-tier cities? And these are the places that are driving economic development in China. And so every time I advise people about doing business in China, it’s always about like figure out the second and third-tier cities that you want to go to, develop relationships with local officials and just talk to them, talk to them, and spend time. The second piece goes the other way, Chris, and I was in a call with an executive not too long ago. I was just like, “We need to get back to lobbying.”

How many times have you picked up the phone and called Joe Biden? Please, please, please, please, because we need … I think Kurt Campbell is wrong. I think the competition model is not right. We need to get back to a model of engagement. The engagement model was correct. So, those two things, local economic development and local connections and engagement policy and lobbying the US government for that. Those are what I believe in.

Chris: Yeah, makes a lot of sense. Thank you for all those reflections. I’d like to actually pivot a little bit in the last few minutes of our call, and it’s been great to hear about Apple, Tesla, political economy, competition, cooperation, et cetera in the current day, but one of the things I’m really curious to hear about that I think will be really interesting to our listeners is your early work in China. So you were a doctoral student in 1994, riding, I think, a Flying Pigeon bike around Shanghai, visiting factories and talking to factory managers. I mean, this is ’94, that is super early in the gǎigékāifàng 改革开放 era. So we’d love to hear any, I don’t know, anecdotes or things that surprise you now that you learned back then from your time now, 25 years ago.

Doug: Thank you for that, Chris. It was an amazing moment for me. I mean, I spent time, I think, like you, as an undergraduate studying Chinese language literature history, and then I just became obsessed with understanding China’s transformation. In part, because of the Tiananmen movement. I was just so interested in what happened and how do we get there. And then I find myself, to your question or your point, as a doctoral student doing my dissertation research in 1994 in China. I didn’t have a lot of money, and so I just was spending time riding around factories, riding around on my Flying Pigeon to factories and trying to get all the information that I could.

And I guess one of the lessons from that time, well, I guess there are two, one is, it was a time when China was early in its opening up. And so I was able to do some of what I was able to do because there was an opening, I wasn’t just like going to visits that were arranged by my handlers. I was able to just get on the phone and call people, and people were willing to say like, “Okay, come talk to us.” So, it was a great moment and it was just like this beautiful moment of like China’s opening up. But the second piece that I think was really interesting, Chris, was that, and this is what I always recommend to factory managers or CEOs who are trying to get involved in China.

You got to respect the history and culture. So if you know the language well, and if you can speak and if you can talk and you can drop a few quips in Shanghainese, I mean, you’ve been there, you know what I’m talking about, this is what gets you mileage. And it’s just like one of the interesting things about cultural connection, is I just think if you’re going to do business in the global economy, you’re going to do business in China. I mean, one quick story around this. I recently was just on a phone call with a CEO of a company that wanted to get medical devices shipped from Shenzhen to New Mexico.

And he was having trouble and he asked me to help him. And so I was just on the call and they didn’t introduce me, but I was like, “Well, who’s your Chinese translator?” And the guy said, “Well, the person in Shenzhen she speaks Chinese very well. So we’re just relying on her.” I was like, “You’re kidding me, you’re kidding me. Really, really that’s what you’re doing.” And then as I’m on the call and listening, she’s not saying the same things to her CEO, the CEO that I’m representing was saying. And so at some point I jumped in and I spoke Chinese and it changed the dynamic of the call because suddenly they were like, “Oh, we’re not …”

The guy after we got off the call, the guy was like, “What did you do? What did you say?” I’m like, “Dude, you just can’t do that. You have to have people who understand language and culture.” And that’s what I think is the big lesson of this, is if we’re all going to continue to work together, you got to have people who understand language, culture, political economy.

Chris: Yeah. Couldn’t agree with you more. I mean, that’s why all my teaching are focused on doing business in China and I know that your current role at Thunderbird, I mean, that’s a big focus of your work as well.

Doug: Yeah. Well, thank you, Chris. This has been such a great conversation and I hope I was helpful.

Chris: Totally, really, really. Thank you so much, Doug. I appreciate you being with us on China Corner Office.

Doug: Always happy. Talk soon.