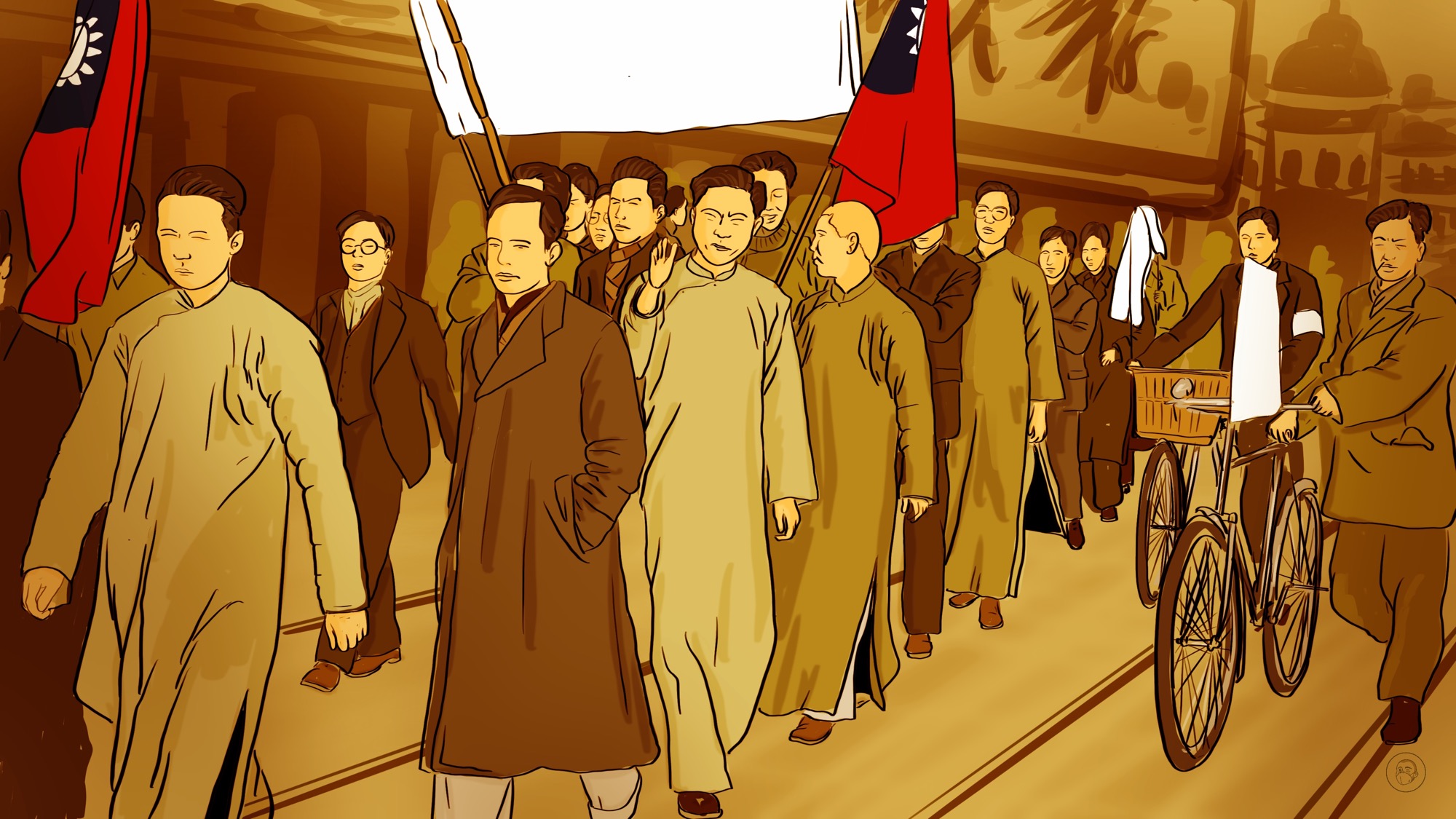

An anti-American protest during the Chinese Civil War

At the end of World War II, more than 100,000 American soldiers were stationed in China, and tens of thousands still remained by 1947. One newspaper alleged that American forces were responsible for one Chinese death every day. And then there was the Shen Chong rape case, which galvanized popular opinion against the American presence.

This Week in China’s History: February 9-10, 1947

A crowd gathered in Shanghai on February 9, 1947. Depending on who you asked, they were there to protest American occupation and brutality, oppose their own government’s economic policies, rally for peace between the Communists and Nationalists, or support China’s alliance with the United States. Nor surprisingly, given this range of motivations, the gathering did not remain peaceful. By evening, one person was dead — a department store worker named Liang Renda — and nine others were in the hospital recovering from injuries.

A thousand miles up the Yangtze, in Chongqing, no one died, but dozens of protesters — mainly students — were hospitalized when government troops attacked a propaganda team of the Anti-U.S. Brutality Association. The association had offices in dozens of cities, all working to end the Chinese government’s alliance with the U.S.

Human society rarely changes overnight. With that in mind, it has become almost a cliche among historians to note that the big watershed dates obscure more than they reveal, as if the bright light of a shiny date washes out the specific features surrounding it. Sticking with that analogy, it is even harder to discern detail when two of these watershed dates are close to one another. For that reason, among others, China between the Japanese surrender of 1945 and the Communist victory of 1949 is often ignored, often dismissed in just a phrase — “the civil war” — that elides all individual events from the end of World War II to the founding of the People’s Republic.

But the events of that period are complex and revealing, not as resolutions of the Japanese occupation or foreshadowing of what would come later, but worthy of understanding in their own right. These events sometimes confound our preconceptions, or help explain larger trends.

Unpacking the various motivations of these two exposes the various threads that came together in early February.

The most obvious concern to most of the crowd was the economic crisis confronting the city. Inflation was destroying people’s livelihoods, wiping out savings. Newspapers reported that prices were doubling every few days, and China’s currency was of little value: at the start of January, the official exchange rate was about 3,000 Chinese dollars to one U.S. dollar. A week later, the unofficial currency exchange was giving around 6,700 Chinese dollars. By February 10, that rate had climbed to some 11,000:1.

Adding to general frustration with this state of affairs, Chiang Kai-shek’s (蔣介石 Jiǎng Jièshí) government announced a plan to tax imports 50% in order to subsidize exports. The effectiveness of these measures to heal the economy was debated — exporters noted that the subsidy they were promised was already swallowed up by the crashing exchange rate. The idea was floated that a boycott would buttress Chinese manufacturers and stabilize the economy.

Only one country was doing a lot of exporting in 1947, and the boycott targeted the one economy that was sending its products abroad in large numbers: the United States. This in turn fed into anti-American sentiment that was already at fever pitch, primarily because of the presence and behavior of American troops.

American troops had taken the surrender of Japanese occupiers in 1945, and by the end of that year there were more than 100,000 U.S. soldiers in China, mainly in coastal cities. The number declined throughout 1946, but tens of thousands remained, and many Chinese were not happy about it. In his article appearing in the journal Twentieth-Century China, historian James Cook wrote that Shanghai’s Lianhe Wanbao newspaper alleged in October 1946 that American forces had been responsible for the death of one Chinese every day since the end of the war. Cook listed some of the crimes: a man run down by a truckload of drunken American soldiers; a rickshaw puller beaten to death by a U.S. sailor; a beggar pushed to her death in a river by U.S. Marines in Tianjin; drunken marines shooting out power lines in Beijing (then named Beiping), cutting power to half of the city for two hours; a Chinese boy scout killed when marine target practice “got out of hand.” Alcohol was often abused, and adding to the outrage, drunken culprits were often acquitted of crimes because what they had done had been “mistakes.”

The distillation of all these crimes came in late December, when two American marines were arrested for the rape of a Chinese college student walking home from the movies on Christmas Eve. The Shen Chong rape case galvanized Chinese popular opinion against the presence of American troops. In the last week of December, marches of as many as 30,000 people protesting American brutality were taking place in major cities across China. Many were demanding not only the punishment of the perpetrators, but the total withdrawal of American forces from China.

With the court martial and sentencing of the two Americans, the major protests subsided, but not completely — as events in Shanghai show. Moreover, the target of the protests was not narrowly on the rape case, but on the government’s relationship with the the United States, its attitude toward the Communists, and the Civil War.

The protest in Shanghai was not just economic. Addressing the gathering was Guō Mòruò 郭沫若, the famous author who would go on to become chairman of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in the People’s Republic. Guo had been a member of the Communist Party since 1927, and was one of the prominent intellectuals advocating against the Civil War. The Communists had been working to change Chinese perceptions of the United States, from a wartime ally to a post-war occupier, a new colonial power attempting to renew the imperialism of China’s “century of humiliation.”

Alongside that fear was the Civil War. Although Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 and Chiang Kai-shek had pledged to work together after the Japanese surrender, armed conflict had reignited in the summer of 1946, and many Chinese were frustrated with their government’s insistence on fighting the Communists rather than concentrating on rebuilding their country and weaning their reliance on the U.S. The anti-war movement was growing, fueled by all these motives, to the consternation of Nationalist leaders.

All these threads were twisted together in 1947. Anger with American occupation, fear of economic collapse, and opposition to the Civil War.

China in 1947 was a compelling reminder that we study the past with the benefit of hindsight. Everyone in Shanghai on February 9 knew that the Japanese had been defeated 18 months earlier, but no one knew that in less than three years the Civil War they were opposing would be over as well, and the insurgent Communists would have established a new country and driven their enemies — including some in the crowd that day — to Taiwan.

This Week in China’s History is a weekly column.