Linda Jaivin on the Wolf Warriors and sissy boys in the metaverse

Q&A with Linda Jaivin, author of ‘The Shortest History of China,’ discusses her latest book, wolf warrior diplomacy, the politics of masculinity, and the empress Wu Zetian.

Linda Jaivin is the author of more than a dozen works of fiction and nonfiction that range from the cult classic novel Eat Me to The Monkey and the Dragon, a memoir and biography of the Taiwan pop star Hóu Déjiàn 侯德健, who played a key role in the 1989 protest in Beijing. Her most recent book is The Shortest History of China, which crams the country’s many thousands of years of history into just 288 pages.

I spoke to her by phone about this week’s news from China, Eileen Gu, the metaverse, and her new book.

This an excerpt from our conversation — the first of a series of weekly Q&As that we’re calling Invited to Tea.

—Jeremy Goldkorn

Jeremy: It’s been a week of rather intense commentary about the Winter Olympics from Uyghur genocide activism to the American-Chinese skier Eileen Gu (谷爱凌 Gǔ Àilíng) , who has been praised and condemned with equal vigor on both sides of the Pacific.

We were both in Beijing for the Summer Games. How do you compare these Olympics to the one in 2008?

Linda: It seems like there’s a bit less riding on this one. The 2008 Olympics were China’s “coming out party,” and every Beijing taxi driver had to be able to speak a few words of English. If you sat in a taxi, there was a wonderful tape recorder that would say “hello, how are you” and “where are you going please?” or something like that. There was an incredible excitement. We shouldn’t over romanticize 2008 either, because don’t forget, just before that event, there were a lot of protests around Tibet and issues with human rights. So China never had a perfect situation. No country does.

But this time, so much has changed.

They’ve got COVID, they’ve got a very different atmosphere in diplomatic relations, and the whole Eileen Gu situation. That has been very interesting because she’s refused to say what her citizenship actually is. She’s playing both sides of the fence. And it’s leaving both sides happy or unhappy depending on how they interpret what she’s doing. I saw that [former Global Times editor] Hú Xījìn 胡锡进 recently cautioned the Chinese people from getting overexcited about Eileen Gu. I think they have a sense that she could go back to America and become completely American again because she has said, when she’s in America, she feels like an American and when she’s in China, she feels like a Chinese.

The thing about the Olympics in China, anyway, is that it’s a state spectacle that fits into a long tradition of state spectacles that are a demonstration of power, authority and glory. And it doesn’t always go as planned. And when it doesn’t go as planned, it seems to have consequences, which is why the Party puts so much emphasis on making it go as planned.

We have a piece out this week on the metaverse, a concept that has soared in popularity ever since Facebook changed their name to Meta. The Communist Party seems to be of two minds about this: should they encourage it or hamper them on security grounds? Is the metaverse a challenge or opportunity for China?

Obviously there’s a lot of advantages for China to get involved in the technological development of the metaverse, but at the same time, what it makes me instantly think of is: How do you censor it? Because that would certainly be foremost on the minds of the Communist Party.

They’ve figured out how to censor the internet. They know how to have bots and real people trolling all the time. And now they have clamped down on effeminate men—on niáng pào 娘炮 (“sissy boys”)—and they have taken them off of [video-streaming app] Bilibili, and other places, videos where these young men dress up in qipao and other very feminine dress and act out various things like the “Peach Boy,” who was very cute.

The Communist Party went absolutely livid over that. Now, what are you going do? Are you going to control what kind of avatars people select? So can a boy not select a girl avatar? And if he selects a boy avatar, are you going to keep him from buying Gucci handbags? It would be so difficult and complicated, much more complicated than it is at present in which people report or discover videos that go against what the Communist Party is promoting. The keywords thing is very easy, but how do you control if a boy goes into a shop and buys a frock?

There are concerns about censorship. But there is also a feeling that this will help China develop the technological know-how and skills it really needs to become the technological superpower that it wants to be and is well on the way to becoming.

So there’s I think a mix of motivations and a mix of problems that the metaverse presents to China.

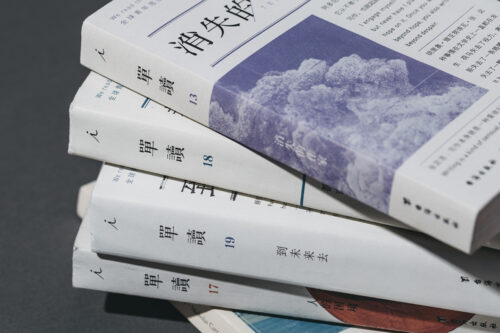

In your new book, The Shortest History of China, you say: “In writing a short history, a wise person might focus on a few key themes or personalities. I’m not so wise. Faced with deciding between key individuals, economic and social developments, military history, and aesthetic and intellectual currents, I choose…Everything.”

One of the things you chose is Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 and the era of the wolf warrior, which gives its name to the chapter. Why are the wolf warriors most representative of our current moment in China?

The reason I chose that as the chapter title is I think that the whole concept of the wolf warriors does encapsulate something very important about the Xi Jinping era. Xi himself has defined his era as the era of “strengthening.” He observed that Mao famously said the Chinese people have “stood up” 站起来, the Deng era allowed people to “prosper” 富起来 and under him, China would “strengthen” 强起来, and that strengthening, under him, has quite an aggressive edge. Now, one of the most emblematic cultural moments in this era, when Xi Jinping took the top positions in party and state in 2012, was this movie Wolf Warrior. And it starred Wú Jīng 吴京, this very ripped action hero.

To get back to that earlier topic about effeminate men, in the state’s masculinity drive, they keep holding up Wu Jing as the ideal Chinese man. This is who we all want to be, ripped and powerful and macho. And in this movie, the second Wolf Warrior movie, he’s kind of a Special Op guy. There’s a terrible hostage crisis in an African country, and he goes and saves the Chinese people, and he saves the Africans from these really horrible American mercenaries and others.

So this image of China being able to protect all of its people overseas, it’s a muscular China, one that doesn’t necessarily obey all the rules. That’s quite interesting too, because he wasn’t on an official mission. It wasn’t like the Dante Lam movie, Operation Red Sea, in which you have an official Special Ops group that goes in and does something similar.

They learned a bit of Hollywood. You gotta have a bit of a rebellious streak to make the hero attractive.

Yeah. A bit of a rebellious streak. But that’s quite interesting. So it’s a China that doesn’t totally obey the rules, but one that not only protects its own people by force if necessary, but it also does right by the developing world. So it’s also protecting those people from whom? From the American imperialists.

Kicking some American imperialist butt basically.

And the tagline for the movie is quite significant because it is a redoing of a Han dynasty general’s admonition that if you invade or cross the Han, we will “execute” you no matter how far away you are. And so they substituted China for this idea of the Han, so you have this tagline that basically reads, “if you cross China” — if you mess around with China — ”no matter how far away you are, we are going to come and execute you.”

Oh dear.

Yeah, this is quite a statement.

And it’s not to say that China is doing that necessarily. For all the worries about various things, China is, for example, aggressive in the South China Sea, but unlike America, which has invaded quite a few countries over the decades to install people into power they prefer, China has not done that yet.

So we have to balance out this hairy chested rhetoric, which is now known as wolf warrior rhetoric, with what’s actually happening.

One stunning recent example of wolf warrior diplomacy was Australia announcing it was having an investigation into war crimes in Afghanistan perpetuated by Australian soldiers. While this inquiry was announced, Zhào Lìjiān 赵立坚, the spokesman for the Chinese foreign ministry and wolf warrior par excellence, tweeted an artwork which was done by a young artist in Photoshop where this Australian soldier was about to slit the throat of a child while they’re sitting on this Australian flag and under the flag were a whole bunch of bodies.

And so it was this highly offensive reaction to Australia’s announcement of an inquiry into its own troops. So that’s classic wolf warrior diplomacy. It actually got the prime minister all riled up.

Scott Morrison, not the brightest bulb in the room!

No, not the sharpest knife in the drawer. He just took the bait and, and therefore the wolf warriors win.

But another very interesting thing was Xi Jinping’s own statement around mid last year that China should present a lovable face to the world.

It shows that perhaps the wolf warrior thing is being dampened down a bit. But that happened after something very interesting: India was in the middle of the pandemic and it was having an absolutely horrific time. There were photos of all those burning pires of victims of COVID and China had just sent up a rocket, so a government agency put onto Weibo the Chinese rocket next to a picture of the funeral fires in India, with the caption “Chinese fires versus Indian fires.”

The interesting thing about this highly offensive tweet was that, immediately, Chinese people reacted to it. There was a huge reaction in China against it because it was so inhumane. And in fact, I do believe that Hu Xijin, when he was an editor of the Global Times, wrote that “we need to be humane.” And he’s the other classic wolf warrior! So for him to say that shows that there is a line. I think that people in the government understand that you have to draw a certain line under this.

Would you agree that Xi Jinping himself really likes the idea of manly macho men?

I remember one of the defining statements Xi Jinping has made was about the collapse of the Soviet Union and his question to his comrades was “Why what nobody was man enough to stand up for the Party and keep the Soviet Union together?”

Is that a fair reading? That he thinks manliness is a good characteristic for the Chinese people to have?

Absolutely. And it’s not just in the aggressiveness of the wolf warriors, the campaign for masculinity, but I think Xi Jinping is constantly looking at the collapse of the Soviet Union. They’ve always been very concerned about that, the Communist Party leadership, but he is super concerned.

Some people are quite confounded by this campaign against “historical nihilism.” What does that even mean? And what historical nihilism means is to tell the story of China and particularly the Party, in the era in which the Party has been active, in a way that goes against the official telling. Now, the reason is because he considers historical nihilism, the loss of control over the historical narrative, to have been one of the factors in the collapse of the Soviet union. You take the manly man, you take control of that narrative, and you can rule forever.

You write in your book that history is of course her story as well. Can you talk about one woman that really stands out?

Empress Wǔ Zétiān 武则天 is quite interesting because she’s one of the few women who’s well known in history. She was an empress. She was very young when she was taken as the emperor’s consort. She was very, very beautiful, but also very, very clever. The emperor during the Tang Dynasty was content to give her a lot of the work of running the country. When he died, she then created her own dynasty. So it was a little break in the Tang. So she had her own little dynasty and is the only woman to have ever ruled China in her own name.

Now what’s really interesting is there’s a lot of stuff that’s thrown at her in all kinds of histories and popular culture. You know, this terrible corrupt, evil woman who took control, and women shouldn’t rule, and this sort of thing. What people often forget is that she helped to give China one of the things that historically it’s most proud of. And that is the system of bureaucracy of government officials built on a meritocracy.

There had been exams based on the Confucian classics for a while, by the time she came in. But then what she did, was she went “okay, what’s going on is that only privileged families are able to send their sons to take the examinations, that probably leaves out a lot of talent.” So she made the exams open to people from humble backgrounds. She made them regular. She said they had to happen at an interval of three years. So she created a system and really importantly, she introduced blind marking. So in the past you would have somebody going, “oh, that’s so and so’s son,” [so the exams had not been previously been very fair at all].

Links:

The Shortest History of China: Buy the book in Australia, U.S.

Linda Jaivin’s website

Invited to Tea with Jeremy Goldkorn is a weekly interview series.