The China Initiative is dead, but its repercussions live on

Advocates say that dismantling the problems behind the initiative will require more work.

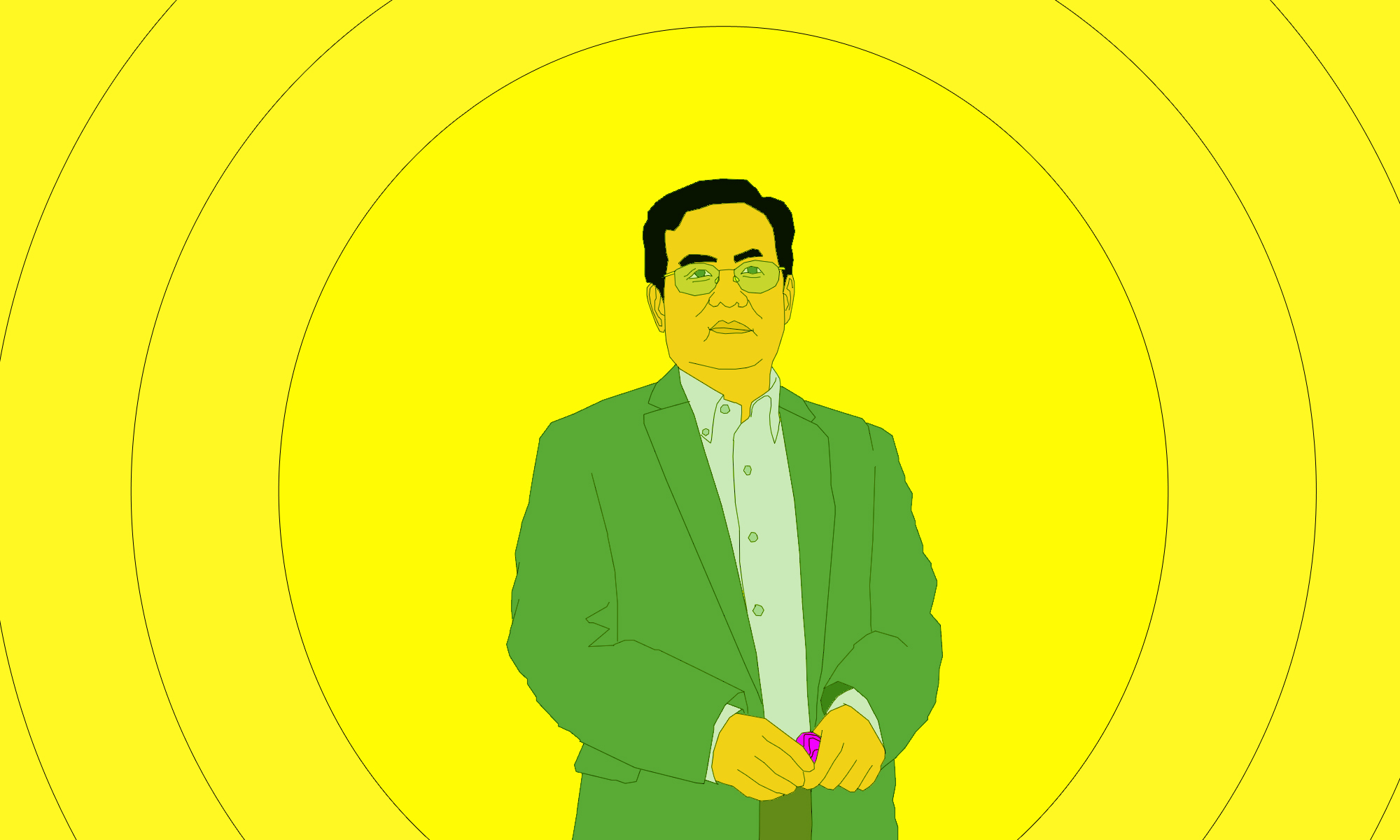

University of Tennessee scientist Hu Anming was first questioned by the FBI in 2018, the year the controversial Trump-era China Initiative was launched. By 2020, he was indicted on wire fraud charges, and then lost his job. Hu was eventually acquitted, but he will forever remain the first academic to stand trial for a China Initiative case.

This past February, Hu finally walked back into his office — weeks before Assistant Attorney General Matthew Olsen announced that the Department of Justice (DOJ) would retire the China Initiative name, explaining that it had “fueled a narrative of intolerance and bias” and “can lead to a chilling atmosphere for scientists and scholars that damages the scientific enterprise in this country.”

“I lost two years of my life,” Hu told Nature. “Who is taking the consequences of that?”

Advocacy groups have celebrated the end of the initiative as an important step in the right direction, but say there is still work to be done to ensure all cases brought forward in the future are based on evidence, not racial profiling.

The government needs to engage more with Asian communities across the country, be more transparent about their practices, and conduct a comprehensive review of pending cases, says Gisela Perez Kusakawa, assistant director for the anti-racial profiling project at Asian Americans Advancing Justice — Asian American Justice Center (AAJC).

“This is a moment of empowerment for our community,” Kusakawa said, adding that the announcement has spurred mixed reactions from Asian-American civil rights organizations and academic communities. “There will be no quick remedy. Undoing the damage done by the ‘China Initiative’ will take some time.”

The initiative had set out to target Chinese economic espionage and trade secret theft in the U.S., but it quickly drew criticism for attempting to prosecute cases that were unrelated to its original mission, using insufficient evidence and focusing overwhelmingly on Chinese and Chinese-American scholars.

A December investigation by the MIT Technology Review found the department had “never actually defined what constitutes a China Initiative case.” Almost 90 percent of those charged were of Chinese descent, while only about 25 percent of cases included charges of violating the Economic Espionage Act (EEA), the investigation found.

Increased concern over economic espionage coming from China began long before the initiative, though; the Obama administration brought forward a record number of cases under the EEA, many of them Chinese scholars and entities.

“I think we have to be honest that there are a lot of scholars who have been very scrupulous about disclosing their connections to the Chinese government,” says Julian Ku, a law professor at Hofstra University. He points to cases that have been successfully prosecuted and says he is hopeful the mistakes made by the department will “scare off prosecutors from bringing cases like that again unless they’re really confident they have a good case.”

The China Initiative had moved the DOJ to focus its resources on a single country, Ku said. “One of the problems was that the FBI agents were just being told to find the Chinese influence. And so instead of just going where the evidence led them, they were looking for evidence even if it wasn’t really there.”

According to Olsen, a review of the initiative began last November. He concluded that the initiative “is not the right approach. Instead, the current threat landscape demands a broader approach,” he said. In place of the China Initiative, the Department of Justice is launching the Strategy to Counter Nation-State Threats, which will focus on threats not just from China, but also from Iran, North Korea, and Russia.

In the future, “academic integrity” cases will be supervised by the National Security Division to assess whether they are deserving of criminal prosecution or warrant “civil or administrative” remedies. And new guidelines from the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) released in January attempt to clarify what kind of international research collaboration is allowed and how it should be disclosed.

Kusakawa and Zhengyu Huang, president of the Committee of 100, are concerned about the impacts of failed cases brought by the department over the past two and a half years and the long-lasting impacts of the initiative on academic and research environments. (Disclosure: The China Project’s owner is on the board of the Committee of 100.)

Many point to the threat of FBI investigation and rising racism against people of Asian descent in the U.S. to account for the steep decline in America’s Chinese students. In 2020, the Trump administration banned thousands of Chinese graduate students and researchers with ties to the People’s Liberation Army.

“We should also be asking the question: who will be held accountable for the wrongdoing of the failed prosecutions?” Huang said.

One anonymous STEM professor from a New England research University, who received his bachelor’s degree in China, told The China Project that he still has faith in the American justice system, but believes prosecutors were “infected by politics.” “Unfortunately the impact has already been made,” he said.

Lin Zhang, a professor of media studies at the University of New Hampshire, is pursuing research related to the China Initiative. She says Olsen’s announcement amounts to nothing more than a name change: many of her friends have considered leaving the U.S. for China or other countries in the aftermath of the initiative (and also due to growing anti-Asian racism across the country).

She adds that dismantling the problems behind the initiative goes deeper than just ending the government program; Zhang is concerned about the lack of meaningful engagement with China and how expertise is being used — or misused — by some.

“There are less people getting interested in the culture and society and establishing business ties there. Now it’s more about security, you are understanding the other because you want to contain them…so if that stays the same it doesn’t really help.”