The quintessential Chinese rifle prepares for retirement

China's rifle, the Type 95, was inspired by the utility of the AK-47 and the efficiency of the M16. It is both a practical firearm and a symbol of China's military development.

By the time Eugene Stoner and Mikhail Kalashnikov sat down at a shooting range outside Washington, D.C., in May 1990, the two men were already intimately familiar with each other’s inventions. Kalashnikov’s AK-47 had changed global history by putting reliable automatic firepower in the hands of peasant armies and freedom fighters. Stoner’s M16 was the black rifle that the Americans built to counter it.

Their meeting was possible because the Cold War was over, and the USSR was slowly disintegrating. The two designers seemed uninterested in this, however, as they cordially shot the breeze through an interpreter.

Notably absent from the meeting was a representative of the third pole in the late Cold War world order. But perhaps both had China on their minds. Stoner had just returned from there, and Kalashnikov was about to go.

The man both of them met was Duǒ Yīngxián 朵英贤.

China’s long road to making its own rifle

“In the northeast,” Duo recalled in a 2011 interview, talking about the time before China’s liberation, “they used Japanese rifles. In Shanghai, they used American guns. Down in Yunnan, they had French guns. In the northwest, it was Russian equipment.” After 1949, the Soviets had provided weapons and plans to make more.

Duo, then in his 20s and fresh out of the Beijing Institute of Technology, was put to work under a Soviet advisor. Not unlike Kalashnikov and Stoner, Duo was an inveterate tinkerer and problem solver, but little innovation was required. The Soviet advisors would not tolerate deviations from their schematics, so Duo’s work focused on materials and manufacturing processes. The only goal of the Chinese small arms industry was to make as many AK-47s and SKS rifles as possible.

In the end, the Soviet advisors went home. Chinese leaders charging Nikita Khrushchev with revisionism cut the country off from Soviet small arms advances. It was a chance for China to produce its own weapons.

A mood of self-sufficiency prevailed. As Duo says, “For a country as big as China to always make things — second-rate things — given to them by someone else wasn’t right.” But designers were hampered by the limitations of manufacturing facilities. They were usually restricted to modifying Soviet designs. Most innovation focused on trying to figure out how to make SKS semi-automatic rifles shoot faster and the automatic AK-47 more controllable (confusingly, both have similar names in Chinese, the SKS variant being the “Type 56 semi-automatic rifle” [56式半自动步枪 shì bànzìdòng bùqiāng] and the AK-47 being the “Type 56 automatic” [56式自动步枪 shì zìdòng bùqiāng]). The Type 63 and Type 66 rifles, the pinnacles of 1960s small arms development, were made using modifications of Soviet designs.

The exodus of Soviet advisors could be overcome; domestic politics were harder to escape. Arms development was not completely disrupted, but even the nuclear program was occasionally affected by the headwinds of the Cultural Revolution. It wasn’t until Lín Biāo’s 林彪 position within the military was weakened (this was made permanent by his death in a plane crash in Mongolia in 1971) that the Central Military Commission held meetings to seriously push forward a small-caliber alternative to the AK-47 and SKS.

The Soviets had switched from 7.62×39mm to 5.45x39mm for their latest rifle — the AK-74 — and the Americans had dropped the M14 and its hefty 7.62×51mm cartridge in favor of the M16, chambered for 5.56×45mm. Small, powerful rounds meant an infantryman could carry more ammunition. The speed of the smaller round and its ability to rattle around in the human body made it potentially deadlier.

The Central Military Commission gave the job to multiple work units who went to work simultaneously on the problem. Nowadays, this is remembered as an error of leftist extremism, but at the time it was called mass participation. Rifles and rounds with varying levels of quality control were produced around the country, all incompatible with each other. It took eight years to settle on 5.8×42mm as the new round, but there was no rifle in mass production that could fire it.

In February 1979, when the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) crossed the northern border of Vietnam, they were still carrying variants of the AK-47 and the SKS. When they dragged themselves back across the border a month later, it was clear that mistakes had been made.

Tens of thousands of PLA troops were killed. The weaknesses of the force had been exposed. They were at a tactical disadvantage against mobile infantry and they were outgunned. Even though both sides were fighting with Soviet knock-offs and hand-me-downs, the matchup was often between Chinese soldiers equipped with the semi-automatic SKS and Vietnamese fighters with the automatic AK-47.

The first response to the mismatch of firepower in Vietnam was the Type 81 rifle, developed by Wáng Zhìjūn 王志军 in the middle of 1979. He cut corners, borrowing heavily from the neglected Type 66. The boys at the front needed a new rifle as quickly as possible. Prototypes were being sent to the border by 1984, and the rifle went into full production by 1986.

The military wasn’t satisfied with modifications of Soviet designs and spare parts. They wanted a Chinese rifle.

The job was given to Duo Yingxian.

Combining Soviet and American designs

Duo had proven himself to be a capable designer with his Type 67 machine gun. Since the 1970s, he had been involved in attempts to make a rifle for the small-caliber high-velocity 5.8×42mm round. But the PLA’s experience in Vietnam gave more urgency to the new rifle. “We had struggled for more than 10 years without producing anything,” he said. “Then they told us we had two years to complete it. We had to catch up with what foreign countries were doing.”

Duo was given a degree of autonomy that he had never enjoyed before. By the late 1980s, a gust of reform was sweeping through the bureaucracy. Duo’s unit at the Fifth Ministry of Machine Building was reorganized under a new Ministry of Ordnance Industry, and its research facilities were placed under China North Industries (Norinco). The watchwords were decentralization and marketization.

It was with the new rifle in mind that Duo invited Stoner and Kalashnikov to China.

The American designer came first. He was given a tour of the No. 208 Research Institute and he delivered lectures in five cities. Less than a year before President George H.W. Bush would slap sanctions on China for its crackdown at Tiananmen (sanctions that restricted arms sales), Stoner’s visit was a high point for Sino-American relations and military technology transfers.

Kalashnikov came next. He vowed never to visit after seeing a newsreel of the aftermath of a People’s Liberation Army ambush of Soviet troops on Zhenbao Island in 1969, but any hard feelings were put aside as he praised the Chinese arms industry and spoke about Russo-Chinese friendship.

Kalashnikov’s visit was mostly ceremonial. Stoner was taken more seriously. To the Chinese, the M16 was the superior gun: it shot straighter and was more versatile than the AK-47 or its successors — but it had taken years of development and failures in the field to get there. Duo wanted to avoid the problems that had plagued the rifle upon deployment. He wanted to know how and why the M16 had been consistently updated since the 1960s.

When Duo and his team went to work on the Chinese rifle in the early 1990s, their dream was a rifle as rugged as Kalashnikov’s inventions and as elegant as Stoner’s M16. Not only should it be a purely Chinese creation, but it should announce the power and ingenuity of the nation by surpassing all foreign designs.

That rifle was the Type 95.

China’s rifle

The Type 95 (also known as the QBZ-95) went into production at the end of 1995, but was held back so that its debut could coincide with another bit of history.

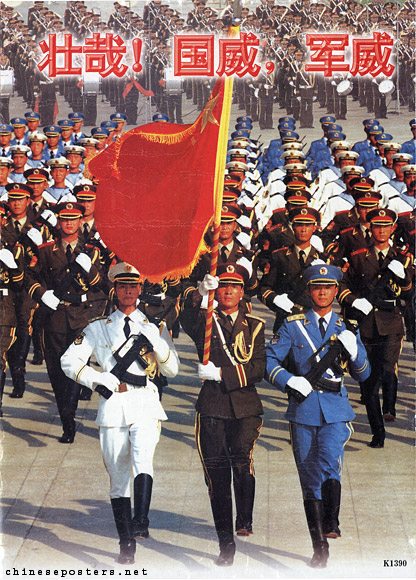

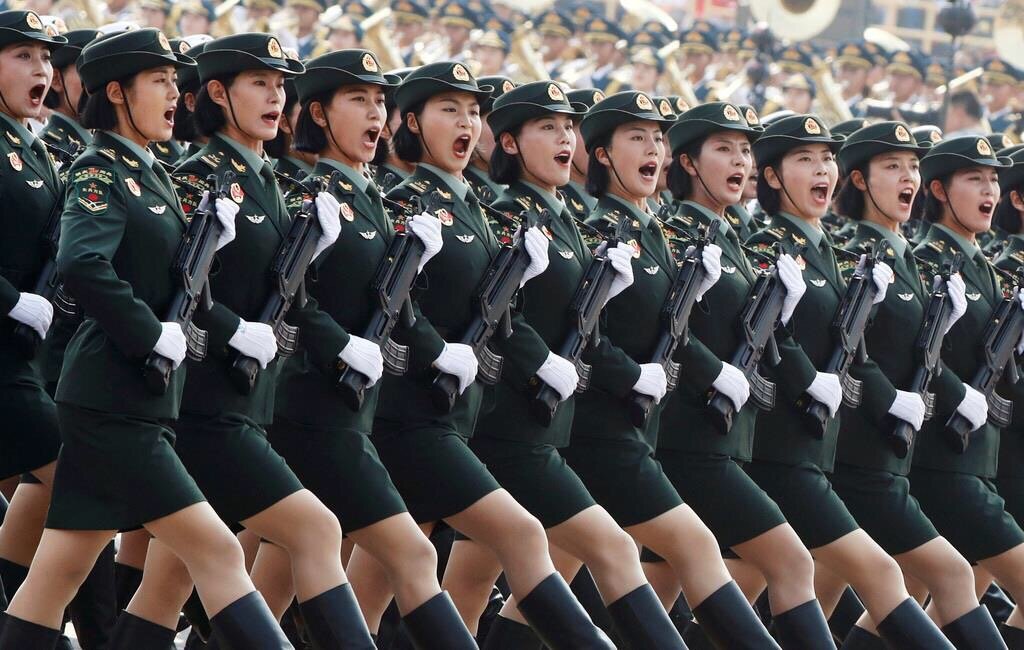

The first time most people saw the gun was at the 1997 Hong Kong handover ceremony, carried in the arms of PLA forces returning to claim the British colony. Propaganda images that had once relied on the Chinese AK-47 variant switched to depicting the Type 95.

It does not look like an AK-47. The choice to move the action of the rifle behind the trigger is practical, but it also throws off the aesthetics of the gun: the magazine coils down off the butt of the rifle like the tail of a mechanical cat. There is no wood to temper the futuristic chill. There is no chromed metal to suggest where your eyes should linger. The sleek slab of black plastic and steel is disconnected from the revolutionary past. It is a triumph of postsocialist industrial development — turned out under a decentralized corporate structure, built from phenolic polymers that had not existed a decade before, and with its elegant gas piston system requiring parts machined with extremely high tolerances and absolute consistency.

There is clear pride in the weapon within the military. The emotional voiceover to a typically lavish and laudatory CCTV documentary devoted to “China’s rifle” tells us that it is “a symbol of our nation’s strength” and “the result of enduring struggle, determination, and faith.” Writing about the special, singular affection that the PLA has for the rifle (the phrase he uses is qíngyǒudúzhōng 情有独钟), a veteran comments that it comes down to it being a distinctly Chinese creation, built specifically for the needs of Chinese soldiers. Through the 2000s, when designers began developing a replacement for the Type 95, they were instructed to retain the outline of the original. The Type 95-1 that debuted in Hong Kong in 2017 to mark the 20th anniversary of the handover was revamped internally but retains the same silhouette.

As PLA veteran-turned-CCTV-7 host Wú Jié 吴杰 put it: “The first time you see the Type 95, you’ll probably be — like I was — astonished.” Few have noticed the rifle enough to be astonished by it, though. Outside of enthusiasts, analysts, and habitual viewers of state television military affairs programming, few outside of China can name the rifle that PLA troops carry.

Duo Yingxian enjoys a reputation in China equivalent to Kalashnikov and Stoner in their homelands. But there is a happy reason for Duo’s obscurity outside his country: China has not gone to war with the Type 95, and it has not been extensively used in global conflicts (the ongoing civil war in Myanmar is the place where it has seen the most action).

The Type 95 will remain China’s rifle for at least a decade to come, but its replacement — the Type 191 — has already been glimpsed in parades. Its designer, Wáng Guānghuá 王光华, is a Duo Yingxian protege, working out of the same facilities that created the Type 95.

We can only hope that in the future, the Type 191 and its designer enjoy the same low profile as the rifle they are replacing.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story said the Soviets switched from 7.62×39mm to 5.8×42mm for the AK-47, but the correct caliber they switched to is 5.45x39mm. We regret the error.