China’s first generation electric cars are dying and no one knows how to deal with their batteries

The small number of approved battery recycling companies can’t get their hands on retired batteries, which are mostly disappearing into small and often unsafe workshops.

Last week, the World EV and ES Battery Conference took place in Sichuan Province. At the conference, a testy exchange occurred between Robin Zeng (曾毓群 Zēng Yùqún), Chairperson of electric vehicle (EV) battery manufacturer Contemporary Amperex Technology (CATL) 宁德时代, and staff from “lithium king” Tianqi Lithium 天齐锂业, which started a battery recycling business in 2017 that achieved revenue of 896 million yuan ($132.53 million) in 2021, a year-on-year increase of 214.07%.

Zeng stated that at CATL, the recovery rate of nickel, cobalt, and manganese in retired batteries has reached 99.3%, and lithium has reached more than 90%. Tianqi Lithium staff responded to Zeng by saying that lithium recycling is theoretically possible in a laboratory, but cannot yet be applied commercially. To this, Zeng replied, “come and see CATL’s advanced technology”.

According to an exhibition at the conference, at least 18 kinds of resources can be recovered from waste vehicle batteries, and 11 types of products can be produced for use in construction machinery, vehicles, and energy storage. With the relentless rise of the electric vehicle and battery industries since 2015, China may already have produced as many as 10 million new energy vehicles (NEVs) with a cumulative battery capacity of 500 GigaWatt hours (GWh). According to an industry estimate based on incomplete statistics, by 2025, China’s leading battery companies will have total production capacity of 2,500 GWh — 16 times the production capacity in 2021 — with the ability to support an annual output of 56 million NEVs.

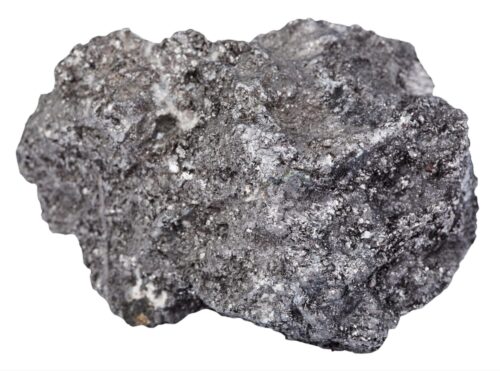

This multitude of NEVs will bring a new problem: As the service life of NEV batteries is usually 5-8 years, China is now fast approaching its first tide of battery retirements, and considering the difficulty and great expense of mining the various materials necessary for producing electric batteries, including lithium, cobalt, and nickel, the need for recycling is obvious.

- For example, the price of lithium salt increased from 57,000 yuan ($8,431) per ton at the beginning of 2021 to a high of 503,000 yuan ($74,402) per ton this year.

According to one Chinese research institute, the estimated retirement volume of lithium batteries in China reached 512,000 tons in 2021, of which 299,000 tons were recycled. According to one forecast, electric batteries will be retired at an average of 20-30 GWh (or 160,000 tons) per year over the next five years, and (according to another forecast), will reach a cumulative total of 780,000 tons by 2025.

The context

From 2016, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology has issued a series of policy documents to set up a system of electric battery recycling. In 2018, the Ministry released a list of companies that meet the specifications for electric battery recycling, including GEM 格林美, China’s largest battery recycling company, which plans to recycle 200,000 tons of batteries by 2025, more than 20 times the amount it recycled in 2021.

With more additions over the succeeding three years, as of 2021 the “white list” contained a total of 47 companies. Nevertheless, new entrants have rushed into this emerging industry: Battery recycling companies increased from 3,000 in 2021 to 24,000 this year and are rising by the day, but so far, only 47 companies are on the white list.

The recycling industry is thus bifurcated into a small number of whitelisted companies with huge recycling capacity (the five largest companies on the list have a collective battery recycling capacity of 600,000 tons) that can easily account for the entire supply of recyclable batteries, and a swarm of non-whitelisted companies. In practice, only about 25% of retired batteries ever reach whitelisted companies, the vast majority of them (including almost all the batteries produced before 2018, when codes were added to the batteries, making them fully traceable) are sold by private NEV owners to the multitude of non-whitelisted recycling companies, who are not subject to government specifications and can thus pay a higher price for batteries that are not traceable at all.

Hence the elite state-mandated battery recycling companies only get a small slice of the battery recycling pie, and the vast majority of batteries disappear into an uncontrollable and untraceable growing miasma of thousands of companies. On June 23, a domestic newspaper searched for “power battery recycling” companies on the business database Qichacha 企查查 and found 57,244 results for related companies. A month later, on July 27, the same search returned a total of 62,157 entries.

Most of these companies are small workshops with little if any investment in safety and environmental protection. In addition, a complete set of industry standards for battery recycling is still lacking in China.

The takeaway

China’s NEV industry is on the cusp of its first wave of battery retirements, but China still lacks a standardized power battery recycling system.