A day in the life of Xu Zhangrun

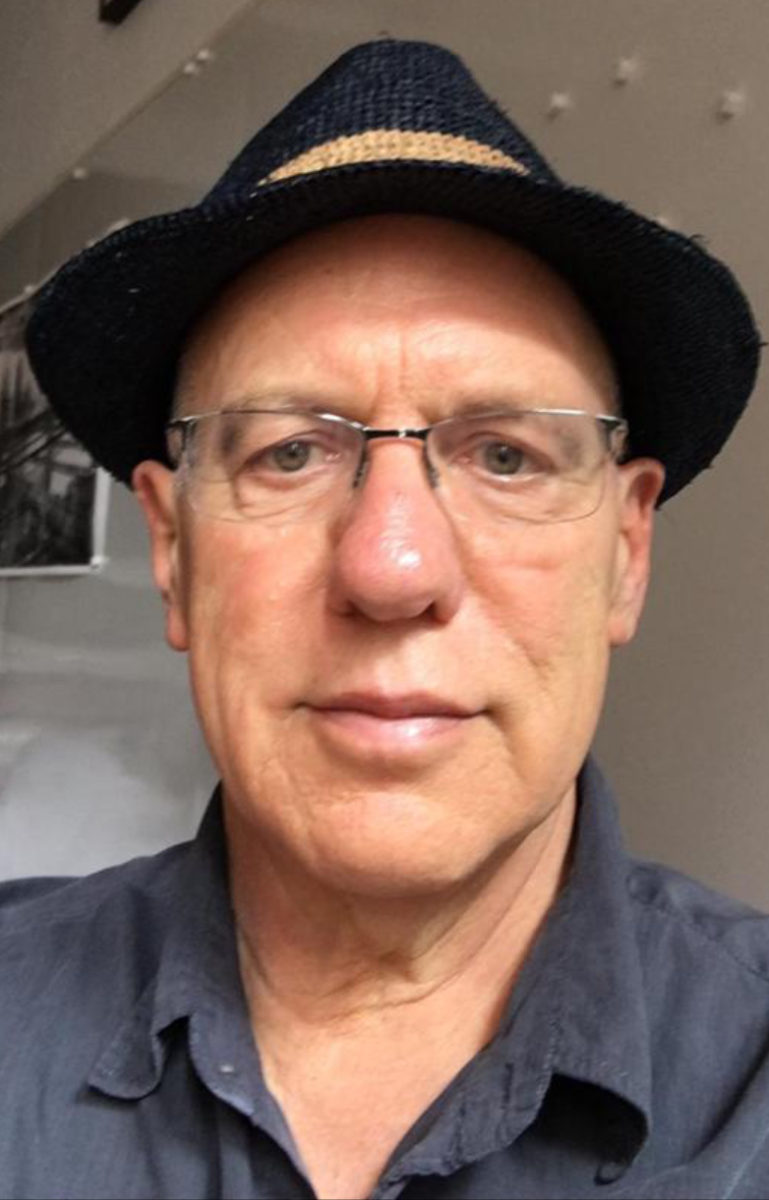

Legal scholar Xu Zhangrun, formerly of the prestigious Tsinghua University, has been a pariah in Beijing since he wrote a takedown of Xi Jinping four years ago. In this work of creative nonfiction introduced and translated by Geremie R. Barmé, Xu takes us into his new life as a social outcast.

Xǔ Zhāngrùn 许章润 came to international attention in July 2018 when he published Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes, a detailed critique of Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 and the first five years of his rule over China’s party-state.

Xu’s jeremiad was written in literary Chinese, a vehicle perfectly suited for what was a scarifying, and often humorous, dissection of Communist Party policy free of the “word jail” of Party jargon. In that critique and subsequently, Xu declared that the fundamental nature of the Communist Party:

…has remained unchanged and, whenever it has weathered a crisis, the Party merely redoubles its efforts. Whatever it may achieve is always hamstrung by the energy it puts into denying all other political possibilities and by its dogged refusal to evolve. The obdurate pursuit of power and the insatiable appetite for self-approval have created a system that, at its heart, is paranoid and brittle.

As an educator for decades, Xu trained cohorts of legal scholars and practitioners who from the 1990s were part of a broad quasi-official and civilian network of social change. (For details, see A Letter to My Editors and China’s Censors and A Farewell to My Students.)

For his troubles, and his obdurate refusal to back down — he continued to lampoon the Party and excoriate Xi Jinping personally over the following years, an effort that included an unforgiving analysis of China’s COVID-19 response, released online in February 2020, and a lambasting of Xi, “an autocratic roué,” published by the New York Review of Books in August 2021 — Xu Zhangrun was fired from his job as professor of jurisprudence at Tsinghua University in Beijing, stripped of his pension and his academic and pedagogical accreditation, and denied the right to travel, undertake research, or publish. He was even cut off from offers of financial assistance from friends in and outside China. For all intents and purposes, since July 2018, Xu Zhangrun has been a “former person,” a remnant of the pre-Xi Jinping era, and a reminder of the more enlightened hopes of the People’s Republic of China.

Becalmed in Beijing and under constant surveillance, Xu Zhangrun is a rare outspoken witness to the Xi Jinping decade. The following account offers readers an insight into the contours of “social death” in China today. It follows on from an earlier work published under the title Composed of Eros & of Dust — Xu Zhangrun Goes Shopping.

This translation marks four years since Xu issued his original jeremiad and it was done in anticipation of the 20th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party at which it is presumed that Xi Jinping — “The People’s Leader” — will continue his suffocating tenure.

“Reports of my social death are no exaggeration”

Xu Zhangrun

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

Dawn of a New Day

The rain-drenched summer means that after years of cruel drought the North China Plain finally has something to celebrate. That’s why, shortly after breakfast this morning, I was surprised to see that for a change the sky which has long been darkened by storm clouds was clear. For some reason it brought to mind that hard-won breathing space between the two world wars; I knew that this patch of clement weather might be similarly short lived.

The puddles on the ground sparkled in the dappled light created by the shadows of the trees and they seemed to be dancing in time with the joyous song of the birds that were flitting around the branches above. Everything was stirring back to life as though momentarily freed from a long period of torpor. Like a clarion call, this set my thoughts racing. Faintly at first — the mere gossamer of a hint — it gradually swelled into a crescendo, enticing me to go out for a walk.

Long forbidden by the authorities from leaving Beijing, and with no real reason to go anywhere even close at hand, I initially confined my rekindled sense of ambition to the grounds within our walled and gated residential compound. Even here [to quote the I Ching] I could “take in the broad heavens and appreciate the vast earth”, and ruminate thereby both on worldly affairs and the caprice of history. Once again, my mind could wander unfettered; it may take flight even though I cannot.

Taking the Morning Air

When I stepped out I made a point of saluting each and every one of the nine surveillance cameras and microphones that were strategically located around the entrance, windows and access points of my humble dwelling. I gestured at them as though I was greeting a long-lost friend or encountering an old acquaintance visiting from some far-flung land. As I walked towards the entrance of the compound — a journey of a mere 7 or 8 minutes — I encountered quite a few of my neighbors who, like me, were taking advantage of the clear weather. Some were walking their dogs as a family, others were just out to enjoy a solitary stroll. Everyone studiously ignored each other as they passed by in silence; they were so focussed on enjoying the break in the weather, I guess; they had no time for anyone or anything else.

The community garden maintenance brigade was also out in force and they were busy clearing water channels, mowing lawns and pruning bushes and trees. The team is made up of farmers in their 50s and 60s hired from the nearby villages. It was the kind of casual and light work that they could easily do during the down times on the farm. Over the years I’ve seen quite a few of their number grow old and pass away.

Usually I’d stop to have a chat, in part because it gave me a rare opportunity to speak to someone — I am reduced to such a solitary and isolated existence now that I’m keenly aware that I need to get as much practice at speaking as I can before I lose the power of speech all together. A particular concern is that these long periods of enforced silence will serve to hasten my cognitive decline and lead to early senility, even dementia. I don’t want to lose any basic communication skills. After all, when I’m stricken and in pain I want at least to be able to call out for help.

One member of the garden brigade was a fellow everyone called “Old Zhang.” His leathery skin had been burnished dark by years in the sun. Lifting the rim of his hat he called out to me in a gravelly voice:

Hey there you, how come you spend all your time sitting on your ass doing fuck all? What’s that about?

I couldn’t really tell if he was asking me a question or making a statement; it certainly wasn’t an order nor did it seem to be an invitation to reply. Old Zhang and the others all knew that the “Mr Xu” of yore had been demoted; nowadays they all simply addressed me as “Old Xu.” They were generally pretty chummy. A slightly younger member of the group — a slightly stooped bald guy in his early 50s known to be a bit of a joker — chimed in from the sidelines:

Since you’ve got nothing better to do, we might as well put you on as an apprentice gardener. You can learn on the job; no one is ever too old to learn a few new tricks. What’s more, you can make a tidy little sum every month, enough to pay for food at least.

Just as I was giving a shrug, my hands lifted up haplessly and my eyebrows raised, a fellow on the other side of the group known as “Old Li” yanked the cigarette out of the corner of his mouth and with smoke billowing around his head declaimed in a raspy voice:

Forget it. No way! We are poor-and-lower middle peasants, salt of the earth types who long suffered under the oppressors in the old society. That makes us rusted-on members of the proletariat, too. Our whole brigade has been politically screened and they’ve confirmed our class bona fides. But this fella here is in the “Five Black Categories”’ [of the Maoist era, who were: landlords, wealthy farmers, counter-revolutionaries, bad elements, and rightists] and truth be told people like him still deserve to be “struggled against, denounced and reformed.” We’ve gotta remind him of his proper place and that he has to be careful to behave himself. We can’t afford to let people like him get up to any of their old tricks. He’d never pass muster!

This screed immediately reminded me of the pitiless class struggles and brutal cacophony of mass political movements of the past. Both from what he said and the way he said it, I knew that this Old Li had to be well into his 60s, otherwise he’d never have been able to regurgitate all that “revolutionary” garbage so fluently. In the normal course of events it was the kind of specialized verbal bric-à-brac best left to the fossicking of intellectual historians.

Before I’d had a chance to say my bit, a shrill voice sounded up behind me. It was like the castrated bleat of someone who’d lost their balls in Zhongguancun [the university district that was once home to many retired imperial eunuchs]:

“The way I see it,” the voice wheedled, “you’re perfectly suited to this kind of work.”

Upon turning I saw that the voice issued from a fellow who looked like some kind of team leader: he was paunchy, had closely cropped gray hair and had an overall hang-dog look. A large key chain was jangling on his belt as he sauntered over. He was around my age — in his late 50s — and his expressionless face served like a disguise, not that he made any effort to conceal the ungainly tufts of salt-and-pepper nose hairs that jostled out of the twin grottoes of his nostrils…He came marching over huffing and puffing. On the surface, he seemed well enough disposed and, then, I realized that his voice reminded me of that of a former acquaintance. Still, I couldn’t quite place him; in fact, I didn’t place him at all, nor could I recall his name.

Throughout my academic career I’d pretty much limited my social interactions to the campus of Tsinghua University. My social life was quite limited. It suddenly dawned on me that this fellow had also been at Tsinghua and I even vaguely recalled that he’d actually been an administrative heavyweight in something like engineering. And here he was, a neighbor in this far-flung spot.

I also remembered that we had occasionally bumped into each other at Tsinghua and had even exchanged the odd word. Our conversations were always limited to such inconsequential things as university policy — the latest news about bonuses, for instance; issues related to performance pay; all the folderal involved in acquitting project expenditures…that sort of thing. He had this tag line, a statement of sorts that he’d invariably blurt out regardless of the context, something forgotten as soon as it was said.

“I’m a remnant from the past,” he’d always say. “It’s crazy that they kept me on at the university after I graduated; after all, I’ve never had a particular talent for any of it.” After he learned that I had also been kept on at the university after graduating, he dropped this particular defense. More recently — that is, over the past year or so — we had pretended not to know each other even on the rare occasions when our paths had crossed, so much so, in fact, that I’d entirely forgotten who he was.

I guess that makes me “one of those superior types who are given to forgetting the small stuff,” as the old adage puts it.

As all of this ran through my mind, I suddenly realized that I’d better make an effort to reply. Now, what I meant to say to him was: “I haven’t seen you for ages,” but I surprised myself by actually blurting out: “Truth be told, it should fucking well be your lot, buddy!” The paunchy middle-aged team leader with the jangling keychain had already walked on and catching my comment he increased both his pace and his panting. Still, he managed to turn his head and let loose a parting shot:

Whatever! At least, unlike you, I’m not guilty of flouting the law of the land and violating workplace discipline!

An Afternoon Adventure

For some reason, I woke from my midday nap in a particularly foul mood and I thought a visit to one of my favorite bookstores in town might lift my spirits. All Sages, the bookstore I had in mind, is located between Tsinghua and Peking universities. Both campuses were now forbidden zones to me and, since I didn’t have any academic affiliation or valid work ID, I was also barred from all of the libraries in the capital. Bookstores, fortunately, were another matter. As commercial enterprises rather than government entities, they still granted me entry.

On that day, I thought to myself that in a bookstore I could roam around the laden bookshelves, my eyes free to hungrily range over all kinds of books and journals. Why, I might even pick something up. Then for a precious moment I would be able to lose myself in some grand mind palace and even make new friends on the page. Despite everything that had happened to me, reading and research remained my true métier, albeit in my unemployed state both were now more of a leisure-time activity than anything else.

Over the years, when I still worked at the university, I’d been in the habit of visiting a bookstore after dinner most nights and I’d happily while away a few hours, lost in the company of books. More often than not I’d return home carrying some new bounty. Rather than drive, I’d take a leisurely walk through the campus to All Sages so that the expedition would double as a daily constitutional. Before I knew it, another evening would have passed in happy distraction.

Since I’ve been becalmed in the western suburbs of Beijing, however, I have to drive if I want to go anywhere. Although the physical pleasure of my habitual book-shopping has been reduced considerably, I still find solace in the thought that driving to a destination makes the whole exercise somehow feel more like a professional undertaking. Anyway, that’s how I grudgingly justify it to myself.

Since my outings into the city were such a rare occurrence, I tried to make an occasion of it. Our floating lives do, after all, consist of just such stuff — getting dressed and putting on a face to deal with the outside world, mechanically setting off to work and returning home, interacting with people of all kinds and exhausting oneself in a myriad of other ways, all part of our quotidian rituals. [As the Song-dynasty poet Péng Yuánxùn 彭元逊 put it:] “Our woes increase year on year akin to the swelling spring waters while our days ebb away like the dying of the east wind.” Ceremony is all about making something particular out of nothing very much, even when it is all comically ephemeral — here I am being all sardonic yet again. I simply can’t help it.

But let’s get back to that book-shopping expedition. I’d arrived at the bookstore and, just as I was making a left-hand turn to go up the stairs into the store proper, I noticed the fellow who was making his way down the stairs, heading in my direction. Our face masks concealed our identities to an extent — I’d gotten into the habit of further disguising myself by wearing a cap that I pulled down to hide my features — but, despite the relative anonymity, I immediately recognized him as a former colleague. Although quite a bit younger than me, he had graduated from the same college and we had even taught at neighboring universities for a time. Although we were never in particularly close contact, we were more than mere acquaintances.

Given my recent troubles, added to the widely-known dramatic deterioration in my personal circumstances [that is: being expelled by Tsinghua University, treated like a pariah, and living under constant police surveillance], I was always careful not to initiate contact with other people or even to offer an unsolicited greeting to anyone from my former life. It’s a lesson that I learned the hard way: Following my fall into ignominy, whenever I made a friendly gesture to an old acquaintance, or greeted someone with an extended hand, I would be unceremoniously fobbed off or, at best, granted an unenthusiastic or grudging response. Now, whenever I was out in public I wore a studiously blank expression. This gave anyone I encountered license to pretend that they didn’t know me; they could pass by as though I simply didn’t exist. Such a tactic lifted the burden of recognition from both parties although, I would note, there were times when I caught a muffled whisper behind my back: “Was that really him?” “Don’t worry, it’s nobody,” came the inevitable reply. Of course, I would continue on my way pretending to be oblivious to what had been said.

[At one point in Bhagavad Gītā Arjuna says:] “I am both the field and the knower of the field [kṣhetram kṣhetrajñam eva ca].” This ancient Sanskrit song about self-recognition resonates with me deeply; I know you know that I know. After all, as living beings we have the same origin, ultimately, we will also share “in the death that devours all.”

In the beginning was the Word; silence reigned before and after creation, be it in heaven or on earth. Even in that universal darkness, however, there was a silent howl.

But, there I go, letting myself get carried away yet again.

When I encountered that fellow heading down the staircase that day at the bookstore you could say that, although we were hardly “enemies who were destined to meet,” we were nonetheless navigating such a narrow path that it did seem as though there was a certain inevitability about things [that is to say, sooner or later most Beijing academics would bump into each other at All Sages Books]. The staircase was just wide enough for two people and it was generally like a busy thoroughfare; at that moment, however, there was just the two of us. Since I had my head down — as per my new habit — I was surprised when he took off his face mask and said: “Teacher Xu, don’t you remember me? I’m so-and-so.” I was so touched that I hurriedly pulled off my own mask so I could offer a respectful response: “Why, hello there, Professor so-and-so”. As we hadn’t seen each other for a few years I half expected that we might actually end up shaking hands or even stop to have a chat so I was completely taken aback when he hurriedly adjusted his mask. As he rushed down the remaining stairs, he threw back an offhand: “I really must invite you out for a meal some time.”

I froze where I stood. I actually had some difficulty processing what had just happened. Meanwhile, he continued on his merry way, stomping down to the bottom of the stairs without missing a beat and turning to exit the building. In his haste he jumbled the long strands of the door curtain striating the gloom of the vestibule with flashes of sunlight. I quite literally rubbed my eyes in disbelief. Upon regaining my composure, I continued my ascent into the bookstore proper, oddly enough with a slightly more determined gait.

Heavens, but there was quite a crowd up there! Most of them had the nonchalant and self-assured air of students. The roomy bookstore café was also packed with young people gazing at computer screens and tapping away furiously. All in all, it was an uplifting sight and I felt somewhat reassured by the studious atmosphere. It also made me regret the fact that I hadn’t been here for a few months. I shared precious little with the gardeners in my compound and the local farmers. Here, however, I felt a sense of belonging. But this train of thought left me feeling abashed. I took stock of the tangle of painful feelings that assaulted me at that moment and quickly quashed them. It all served me right.

But I’m being self-indulgent again.

When you enter the bookstore you are faced with a long, low table that is some ten meters in length and about a meter in width. On it they display a curated selection of recent releases from publishers throughout China. Readers ranged along either side of the display were picking over books that had been selected to appeal to just about every intellectual fashion. I saw a few young people and a middle-aged reader standing on the other side of the display just over from me. I recognized the older man as yet another former Tsinghua colleague, one with whom I’d previously had quite a few dealings. Although I was only a few years older than him, previously he had treated me with the kind of extravagant respect usually reserved for an elder. At the time it had both surprised and, if truth be told, touched me.

But all of that was before I had been “re-educated” in the great school of life over the past twelve months. Anyway, given my recent encounter on the staircase, I was wary of yet another off-hand reception. So I decided to play it cool and pretended to be unaware of our previous connection. However, the youngsters who were there with my old colleague were already stealing glances in my direction. After holding out for as long as they could, one said to the fellow, who was obviously their teacher: “That’s him, isn’t it?” “Yes it is,” he replied. “Now don’t say anything.” His little flock now moved around with what seemed like disdainful care and, for some reason, I ended up feeling as though somehow I was in the wrong. I simply shriveled up inside. After hearing that curt exchange, I kept my head doggedly bowed and focussed on the book in my hands. When I finally looked up, they were gone.

The Remains of the Day

By then it was getting toward dusk and, given that the drive home was over 30 kilometers [18.6 miles], I decided to pay for my books and head out. Before setting off on my return trip, I also picked up a few things at a nearby supermarket — the round trip into town was a pricey exercise, so I did my best to pack in as much as I could.

By the time I got home it was dark. After putting my books and the groceries inside, I felt a vague and unsettled emptiness. That, added to the fact that I still really wanted to take advantage of the clear weather, I went out again to stretch my legs. Who knew when the rain would return?

I immediately happened upon a few dozen workers who’d been doing house renovations. They had just finished for the day and I was swept up along with them. Not having shaved for a few days I’m sure I appeared quite unkempt, but I meandered along with them, lost in the darkling crowd. Transported beyond the everyday and lost in my musings, I was aware more than ever of the unpredictable vicissitudes of life. My desolate mood was underpinned by a certain majestic sense of moment.

As we approached the entrance to the compound I noticed that some buildings there were also being renovated. A large moving truck was parked outside one entrance having obviously just been unloaded. About a dozen students were standing around nearby — after a lifetime spent at a lecture podium I could tell that they were university students with a single look. Anyway, their backpacks and the little soft animal toys hanging off them were an immediate giveaway.

I stood there, transfixed by those young people who were happily chattering away and fooling around. Observing a world that was now lost to me, my eyes welled with tears. The troupe of workers I’d been walking with continued on their way while I stayed back to appreciate the happy banter and shenanigans of those young ones. They were in small groups noisily chattering away. I could pick out a few snatches of their excited conversations: “…final thesis defense is nothing to worry about,” declared one; “you know that teacher in the Marxism Department who is always ogling female students?…,” chimed in another. Then, unrelated: “but his specialty is admin law, so I have no idea why he’s on my civil law panel…” “The topic I originally chose was about infringements of the constitution, but my supervisor rejected it — ‘Don’t you have any idea about what’s going on?’, he said to me. ‘At a time like this, you’re crazy even to think about a topic like that. Anyway, if you’re determined to go ahead with it, you can count me out.’” And then this tidbit: “Are you kidding: you actually want me to say that the Party’s rules are not equivalent to codified law? All I can say is that there are some things that override the laws of the state; it’s just that simple.”

It was easy to tell that they were law students, young men and women pursuing the same field to which I had devoted myself until I was cast out by Tsinghua. Now I was just some random unemployed old guy loitering and eavesdropping on them.

The lights went on suddenly although one doorway nearby remained cloaked in darkness. A middle-aged fellow appeared: he was rake thin, had rimless glasses and was dressed in a short-sleeved shirt and long pants. With a mere glance in my direction I knew he had my measure. Motioning to the gaggle of students to gather around he said in a stage whisper: “You have to have your wits about you in these parts. We’re far from the city center here and there’s all kinds of questionable people in the vicinity. Be sure you don’t talk to strangers. Now, gather up your things and let’s go eat.”

Despite what he’d just said, a few of them approached me politely: “Master [师傅], it’s getting late and you must have had a long day. Maybe it’s time to go home for dinner. We’ve been helping our teacher move house and there’s really nothing worth hanging around here for.” That one honorific term “Master” put an abrupt end to my musings. I mumbled something in response and skulked off. As I did so, I heard someone mutter: “How clueless can you be? Why’s he been hanging around here staring like that? Talk about rude!”

I’d really come to dislike the term “Teacher” [老师], despite the fact that it was generally regarded as being a respectful form of address. “Teacher” had long been devalued and it was applied indiscriminately — to celebrities, online influencers, fortune tellers, and all manner of scoundrels. And that doesn’t include the actual teachers who aren’t worthy of the title. I wanted nothing to do with it and it’s why I’d (only half) jokingly encouraged my own students to address me as “Master” [师傅]. That at least was an expression that denoted a person who could boast of some practical accomplishments. Before long, my students had all called me “Master Xu” [许师傅]. One of them was even so kind as to observe that imperial tutors like Reginald Johnston and even Wēng Tónghé 翁同龢 before him had been addressed as “Master”.

Meanwhile, the term “boss” [老板] proved to be popular among the Tsinghua students who studied engineering and the sciences. Having originated in the business world far from academia, as political power and money had come to dominate everything “boss” had increasingly gained currency at the university. And that’s also probably why it never took hold in our part of the campus.

It would never have occurred to me that I’d end up being addressed by that familiar old term “Master” by students so far from Tsinghua but, then again, I have come to appreciate the fact that the poet who wrote that famous line — “Ah time: your mysterious path leads us to perplexity” — had, like me, drunk life to the lees. It was a poetic line born of the writer’s trials and tribulations. [It was written by Chāng Yào 昌耀, a poet who was exiled to Qinghai in the late 1950s.] These students were guileless and they used the expression “Master” with ill-disguised delight. However, I wouldn’t give their lanky skeleton of a “teacher,” standing there in his billowing pants, the time of day. He didn’t really have a clue who I was and there he stood pretending that he was a scholar of legal studies. What a joke! He had his snout in the trough and deserved absolutely no respect. I wouldn’t give him the time of day.

But, then, I did have to laugh at myself: here was “Master Xu,” a self-important fellow, getting tied up in knots over nothing. Naïve, self-indulgent! I really have to learn to enjoy things as they are and appreciate whatever comes my way….

A Voice from the Void

Back home night had fallen and the only sound to be heard was the chirping of frogs. The sky was overcast once more and it looked as though the rains might soon start up again. There was this one mosquito in my place that had had designs on me for quite some time, and now it was repeatedly dive bombing me in hopes of feeding on my blood. I feebly flicked it away a few times, but soon tired of the pretense and let down my defenses. So what if it drew a little blood? It was a small price to pay for the company of this tiny creature in the dead of night. Anyway, which of us had the greater right to be there?

It was in this pensive mood that I suddenly recalled another recent encounter. I’d bumped into an acquaintance at a parking station. He had granted me the rare honor of actually stopping to chat. Among other things, he told me that my name had come up in conversation when a group of friends had been drinking together a few days earlier. An old professor of ours had even asked after me.

At a loose end this evening, and with no other company than that of the mosquito, I pulled out my mobile phone and tried that professor’s old number on the off chance that it still worked. I was actually half surprised to realize that, for a change, I was doing something that was completely normal and commonplace. My call went through at once and the professor sounded exactly the same, although it soon became obvious that he was now quite hard of hearing. I don’t know why my raised voice attracted more mosquitoes but it wasn’t long before there was an incessant whining around my free ear.

After exchanging some perfunctory pleasantries, the elder became solemn. Getting straight to the point he said:

I’m aware of your circumstances and all I can say is that you must pick yourself up from the very spot where you took that disastrous misstep. They tell me that you even need a cane to walk these days. I still don’t have to use one even though I’m much older than you!

Now, you’ve brought all of this on yourself, as you well know. You made a grave error. Everyone knows you can get away with most things so long as you steer clear of politics. My advice to you is simple: face up to the error of your ways, analyze exactly where you went wrong and clean up your act.

Anyway, I’m not all that well myself. It’s best if you don’t call again.

With that, he hung up.

By ending the conversation so abruptly, and in that way, I found myself reflecting on our relationship. It began in 1983, now nearly forty years ago and I well remember that lustrous North China autumn when I first came to Beijing, a strapping twenty-year-old. I was a real provincial, penniless and pretty much adrift, but I’d got into a graduate program in the capital all the same. This older teacher taught me for a few weeks during my second year. His teaching style was typical of the era: all he did was read out from a prepared text in a monotone. He doubtless thought that he was putting everything he could into his recitation, but we students were far less enthusiastic than usual. It was a kind of pantomime in which both teacher and students dutifully played their part.

He’d been given a university job after graduating, though at the height of the Cultural Revolution when the college was disbanded he was re-assigned to some far-flung public security organization. He got his original job back after the school was re-established [following Mao’s death in 1976] and that’s how we had ended up with our tenuous teacher-student relationship. Like him, I too was allocated work at our alma mater, and in his department as well. Although theoretically we were now colleagues, he was quick to take advantage of my lowly station. He leaned on me to draft a number of academic articles that he subsequently published under his name. It was all part of my “in-house induction.” Or, as he put it, “an excellent opportunity to learn the ropes.” He had readily accepted my unwitting contribution to his career.

Envoi: “We at least are safe”

In bringing this account to a close I should confess that, although I have put these notes together in a way that suggests that these were the goings-on of a single day, in reality the encounters detailed above occurred over the summer of 2021. I’ve woven a whole cloth from these disparate strands and included a few asides to add to the dramatic effect of the whole. After all, my friends, aren’t we all but players in the petty dramas of our own lives?

I’ll conclude with lines from two poems by Czesław Miłosz, the Polish Nobel laureate:

Quality passes into quantity at century’s end.

For worse or better, who knows, just different.

[from “Pierson College”]

And:

And nothingness, as the prophets keep saying, brings forth only nothingness, and they will be led once again like cattle to slaughter. …

They prepare it by repeating: “We at least are safe,” unaware that what will strike them ripens in themselves.

[from “Sarajevo”]

How very right you are, Master Miłosz: they do indeed think “we at least are safe.” For their sake, let’s hope that they are right.

Drafted in the Seventh Lunar Month of the Xinchou Year in the company of a few mosquitoes.

Revised as the autumn leaves were falling, on the Twenty-seventh Day of the Ninth Lunar Month (1 November 2021) at my home by the Old River.

The original Chinese text is below:

一番風月更銷魂

其一

今日家中斷糧,進城採購吃食。事畢腹飢,路過一家日本料理,禁不住嘴饞流涎。稍一猶豫,轉身拐進去。木門開處,幽篁照影,掩映著一方小院。石徑通幽,一廊半敞,正對著這水線環廊的日式庭院。穿廊而過,可以看得見廊下一方方窗口幽幽紗簾後的米白桌布,桌布上的燈光,燈光搖曳中的食客臉龐。男賓女客,對坐施然,觥籌交錯,飛觴走斝,人兒伴明窗。看得見他們眉語目笑,卻聽不見一絲聲息。那笑靨蕩漾,那蹙額凝神的諦聽,那揮手攏臂的模樣兒,讓人想見其情怡然,其心煦然,其生暢然。

這才想起曾經應邀在此酒聚,不止一回。這地兒不便宜,好幾次都是企業家做東,讓我們幾位教書匠飽饕。刻下中文“企業家”一詞,令人想到實體產業經營者(entrepreneur),其實未必。他們可能是地產商,也可能是投機炒股、電商物流或者做進出口生意的,還有可能是某個國企的負責官員,或者,什麼高科技投資公司。反正一鍋燴,都叫企業家,共同特點是要有點兒錢。話說回頭,他們好讀書,愛議論,酒量大,去過世界上許多地方,不少人學歷都很高。每次盡歡而散,人人臉頰飛紅,個個心意著彩。最近的一次是七月中旬從牢裡放出來後,好友特從外地趕來為我洗塵,讓我選址,我假惺惺推辭,他便代我挑選了這家門店。此後夏盡秋來,雨驟風狂,轉眼又是冬月,更是萬木蕭疏。我遠郊孤居,友朋星散,不料想今日進城居然走進了這家門店。

真巧啊,一方窗簾後坐著的是昔日常在此約飯的幾位友人。是的,還是他們,附近大學的三位教授,兩位企業家,還有一位似曾相識的中年女士。我隔簾瞅見他們,腿腳挪不開,情不自禁,便停留了幾秒。沒想到,終於又看到這幾位友人,久疏音問,仿佛隔世,倍感親切。他們看上去都沒什麼變化,我覺得自己也沒什麼變化,或者,我忘記了自己是否有什麼變化。他們也抬頭看見了我,先則訝異,轉而驚喜。一位起身出門,我也笑笑往前邁步蹩進店堂。站在門廳,他跟我握手擁抱,拍肩撫背,千叮萬囑必須照顧好自己,身體最重要,“坐待天明”。——這是在下一篇散文的標題,後來用作了散文集的書名,昔日酒聚大家常用來臨別時相互叮嚀。我說放心吧,每天作息有常,讀書寫字,能熬下去。晨瞰朝霞,暮聽歸鳥,就是腳痛,所以必須策杖而行,遂見滄桑。他再次緊緊擁抱,說時局緊蹙,大家都很鬱悶,今日特請幾位著名教授談天,聽聽他們的高見,“不多耽誤許教授,就此別過”,轉身走了。

我也轉身走了。走過敞廊,走過小院,走出那扇木門。回到大街上,立馬噪聲襲上耳鼓,人間問候來了。剛才站著說話忘記餓了,此刻突感飢腸轆轆,這才想起已是午後時光。附近還有一家中餐館,招牌上寫著川魯湘粵,其實就是家常菜,價格相對便宜。曾幾何時,大家時常在此聚會,輪流做東,海闊天空,不肯閒卻萬卷書。究竟在此吃過多少回飯,記不住,反正不少回。快到店門時,心中突再躊躇,先想回家做點兒吃算了,轉念又想就去這家飯館吃碗麵拉倒。心思轉動未定,腳步早已走在前頭了,其情其形,類似於“宋人議論未定,金兵已然渡河”,可見殺山中賊易,殺心中賊難。也是我今天走運,剛進門,就迎面碰上十幾位教授編輯女士先生們,剛剛用膳完畢,正要回返,四散開去。他們看見我,先是一怔,轉而喜不自禁,圍攏過來,同樣又是握手又是拍肩,笑語喧嘩,加上估計幾杯下肚,話兒也忒俏皮。幾位出版社的女編輯,端莊大方,今天比較矜持,輕輕握手,不像往昔見面,撲上來熊抱再說。原來,剛出了幾本新著,“有一定創見的”什麼法學門類的專書,沒記住書名,但依稀每本書都有什麼“大數據”三個字,加上又有一期雜誌新刊,幾位編輯遂不避帝都路況擁擠,一併驅車給教授們送來了。遠道馳騁,送書上門,是幾位編輯女士先生們的慣常做法。教授作者們也齊心聚合,啟動慣常做法,“略備薄酒”,以為配合,天衣無縫。於是,稱觴歌袖,橫波意酣,賓主盡歡,一派祥和。

領頭的教授,半年前我們還是同事呢,說想念我,“甚為想念”,其餘幾位隨聲附和,莊嚴同慨,更有女士面帶悲戚。領頭的編輯,一位女士,過去一見面就喜歡熊抱我的那位,說早就想給我送書籍和雜誌,但找不到我的聯繫方式,打聽了好多人,大家也都不知道,可惜今天沒帶夠,不然定要送呈敬請指正云云,並表示馬上還要去附近兩所大學的法學院和哲學系,給那裡的教授作者們送去書刊,“任務挺重”。看到他們日程緊湊,為繁榮學術和出版事業忙碌,我一個無業閒人,遠郊進城買菜的,不好多佔他們時間,便說自己有事要走。到底是老朋友,他們萬分體諒,即刻囑我趕緊去辦,不可耽擱,於是彼此鄭重道別。

從我居住的小區至此,三十多公里。我平日就在附近鄉村集市買菜,有時也去鎮上稍大些的超市,買點兒醬油醋針頭線腦牙膏肥皂什麼的。不意昨夜有夢,夢回香江,江邊咖吧酒肆,燈光幽冥,聲色婉轉,衣香鬢影,玉山半倒,勾起了我這個卑鄙無恥的荒淫之徒內心深處對於奢華生活的渴望,加上正好糧盡彈絕,連紅薯都沒了,乃決意開車進城,順帶採買西點,好回鄉居舍下,在平常日子的平常陽光下,一邊晴窗展卷,一邊佐咖享用,哈,慢悠悠,小資麻麻呢。許家一門老小,就我和先嚴喜歡甜點,從來不忌三高,大口啖啖。他活到八十歸西,我不知自己人壽幾何。萬事天定,人力有限,興亡休問,更那堪,“古廟頹垣,斜陽老樹,遺恨鴉聲裡。”今日三生有幸,晌午時分,一刻之內,接連巧遇兩撥友朋與前塵同事,飯沒吃成,倒因為激動之餘說了許多話餓得前胸貼後背,加上老毛病低血糖襲來,便在車上將這幾樣西點,伴隨著市聲騰囂,一口氣狼吞虎嚥完事了。

昊天有德,人間晴好,一番風月更銷魂,美呀!

庚子冬月初六,耶誕2020年12月20日,故河道旁,一彎弦月,

敲鍵記下流水賬,三杯自犒醉風眠。

其二

1

今夏多雨,連日瓢潑,讓這個經年苦旱、時常灰頭土臉的華北平原大城,既驚且喜。不意今日早餐後憑窗抬眼,發現天也倦了,終於放晴,猶如兩次大戰間歇的和平時光,歷經拼殺而來,而來之不易,卻極可能稍縱即逝。日頭從葉縫斜斜漏下,照得水漬猶在的地面影影綽綽,伴和著小鳥從一樹飛向一樹的啁啾。一時間腦海翻波,染神亂志,仿佛心頭忽然一聲,其聲弱如游絲卻又浩瀚若雷,乃擲卷起身,決意出門,溜達溜達。

禁足遠遊,無緣近遊,小區院墻之內走走,仰天俯地,撫今追昔,放飛想象,好像同樣天高地遠。

2

出門上路,跟扇面狀圍攏寒舍而復散開的九個電子監控探頭一一揮手致意,無比親切,好像密友久別重逢,好比他鄉邂逅故知。轉眼七、八分鐘,身前身後,已然閃過好幾位鄰居,或結伴牽狗徜徉,或一己踽踽獨行,例皆旁若無人,彼此默默。看來大家都被陰雨堵在家中久矣,趕緊乘隙放風,無暇他顧。路旁小區物業綠化隊的工人正在作業,疏渠鋤草,整枝打杈。他們是附近村莊的農人,六十上下,說老不老,說小不小。在此打一份工,有一搭沒一搭。十多年裡,眼見著老病相繼,好幾位都沒了。平日相逢,閒聊幾句,算是我操練中文口語,不忘牙牙,否則遠郊孤居,天長日久,生怕癡呆先於老病驟至,喪失人之為人的基本溝通機能,到時連喊痛也喊不出聲來。

黑臉老張看我走來,抬抬帽簷,啞嗓子由遠及近:“我說,你這整天兒坐吃山空,立地吃陷,怎麼整啊?”是疑問句,可能也是感歎句,但絕對不是祈使句,其實不用正面回答。他們都知道“許先生”現在至多只是個“老許”,說話反倒隨意親切多了。另一位稍年輕,怕也有五十出頭,背微駝,頂已謝,愛逗樂,這邊廂搭腔,“不行加入我們綠化隊吧,當學徒,跟著幹,活到老學到老,好歹一月千兒八百的,打醬油管夠。”我身體稍往後仰,一抬眉毛,一攤雙手,還沒來得及回答,那邊廂老李兩指夾著從嘴裡取下的半截煙,渾濁的重低音伴隨著煙霧騰騰滾過來了:“不行,使不得,我們是貧下中農,苦大仇深,無產階級革命隊伍。搞綠化先要政審,審查階級成分。你這五類分子必須接受斗批改,只准老老實實,不許亂說亂動,不合格!”聽話聽音,鑼鼓聽聲,老李一開口就暴露了自家滄桑,怎麼著也得花甲了,不然這些“革命年代”的流行語——今天某個史學領域知識考古學的“專業術語”——是無法朗朗上口的。

還沒等我開口,身後突然有個尖細嗓子接茬,像是中關村裡沒蛋蛋的尿道狹窄患者淅淅瀝瀝時悲欣交集的吟哦:“我看,你幹這活兒挺適合的,你其實就適合這活兒。”返身回視,這才看到一位漢子,小包工頭模樣,灰白短髮,塌眉毛,中部崛起,褲腰帶上掛著一串鑰匙,一搖一晃著蕩悠過來。看上去約莫也是在下這把年紀,面無表情,倒是鼻毛不少,黑白夾雜著伸出洞穴,於鼻翼和上唇的狹窄地帶隨喘氣而招搖。有些面善,聲音也似曾相識,可就是吃不准是誰,叫不上名字。一輩子教書,起居不離校園,校園就是家園,許某著實交遊有限矣。然而情急之下,猛然想起,此君乃清華前塵同事,似乎還是某個什麼機械或者工程系所的頭目,也是同住這個小區的街坊。以前小區碰上偶或閒聊兩句,交換一下“每月獎金多少,績效工資幾何,以及項目費報銷”之類學校的“大政方針”。他有一句口頭禪,可以突然毫無語境地冒出來,來之無影去之無蹤,就是“我是‘三青團’。留學的都扯淡,沒啥真才實學。”後來估計聽說我也是所謂的“留學生”,便從禪林中移走了這句話。這一年多偶爾小區迎頭碰面,仿佛不曾相識,居然慢慢地就忘了。

我真是個“貴人”啊。

思緒至此,趕緊搭腔,想說“好久沒見了呀!”結果一開口居然是“你他媽的才適合呢!”這位腰間一掛鑰匙的中年漢子,凸肚包工頭,此刻已經走到前側去了,聽言轉身,邊走邊加快步伐,邊加重喘氣,邊扭頭回嘴:“不管怎麼著,我沒違法亂紀呀!”

3

心情大壞。午休後決定驅車進城裡的那家書店逛逛,散散心。書店位處清華北大兩校之間,地緣戰略地位顯豁。兩校的大門我都進不去了,大小各種圖書館也因我沒有工作單位證明辦理借書證而無法登堂入室。但書店還能進,畢竟,這是買賣的地兒。遊走於琳瑯書架,縱目於舊籍新刊,一卷在手,目不斜視,三陽開泰,四海他人,既是“專業活動”,在我也算是“娛樂活動”了。故而,許多年裡,晚飯後書店裡消磨兩小時,來回一小時,手拎一捆書,安步當車,這夜晚便滑溜過去了。現下身在遠郊,只能驅車往返,少了娛樂性,但自我安慰好像多了一份專業性呢,呵呵。

來一趟不易,平添一份儀式感。人生一輩子,穿衣戴帽,上班下班,男女大防,人前人後,累死累活,“愁如春水年年長,老共東風日日消”,都是儀式呢。可儀式感,只會偶或浮現,不由得再一次“呵呵”。

話說來到這家書店,進門拐彎上樓,但見二樓梯口一位正要下樓。大家都面蒙口罩,我更且破帽遮顏。但此刻一眼便看出了這位四十來歲的下樓者不是別人,正是一位學生輩的同行。我們先後畢業於同一所大學,在相鄰的法學院任教。不常往來,但還算熟悉。這一年多來的生活,怨寒嗟暑,閱歲經秋,養成了一個習慣,即見到舊識,千萬不要主動打招呼。好幾次主動開口,上前伸手,結果對方不陰不陽,或者搭訕兩句迅疾離去。後來發現,每遇這種場合,只要自己裝作沒認出對方,對方便也佯作不識,擦身而過,失之交臂,兩造都好不輕鬆。有一兩次聽到身後竊竊,仿佛在說“是他吧?”就裝作沒聽見,“不是他”,走開就是了。畢竟,知身知田,梵音梵頌,也就是吾身吾心,自言自語,而一本於萬有,並終歸於“吞滅萬有的死”。

太初有言。此前此後,天地默默,宇宙在黑暗中無聲咆哮。

話題收回來,我與這位下樓者迎面相遇於樓梯,有點兒不是冤家也路窄的意思。確實,本來樓梯不寬,剛容兩人來去,“車流水,馬游龍”。我依舊低頭上樓,結果沒想到對方先自開口,摘下口罩,居然喊我“許老師,我是某某呀”,一時間心中溫暖,也趕緊摘下口罩,以“某教授,你好”恭敬回應,準備站下來聊幾句,甚至打算握個手什麼的。畢竟,好像也有幾年沒見了。但對方迅速重新戴上口罩,疾步下樓,邊走邊說:“改天我請你吃飯啊。”

4

我立定樓梯,一下子有點兒轉不過神來。眼見他蹬蹬下樓,眼見他轉身出門,眼見他消失於視野,眼見門簾兒晃晃悠悠,眼見門口的光線隨著晃悠的律動而忽明忽暗。揉一下眼睛,稍頃釋然,健步登梯,興沖沖。進到店裡,耶,人不少呢。尤其許多青年學人模樣的,或雌或雄,都氣定神閒。送目遙瞰,傍邊咖啡座,也有不少讀者,三三兩兩,面對著電腦,敲鍵不止,真為他們文思如湧而高興。較諸我居地的綠化隊及其農人,此刻仿佛覺得我更屬於這裡,想想差不多兩個月沒來了,似乎有點兒那個慚愧什麼的感覺,爬梳得心裡絲絲抽痛,活見鬼。

閒話少說。店裡一進門擺放的這條長桌,長約十米,寬一米余,展示的都是店主精心挑選的新籍,來自東西南北各地的出版社。看客分列兩側,各自披覽,隨手拈選,你愛蘿蔔,我愛青菜。正對面幾位,兩三位青年,一位中年。這中年漢子是清華同事,也是有些過從的舊識,年齡相差幾歲,但有時承蒙他執弟子禮,讓我感動而心驚。有這一年多的生活教育,特別是剛才樓梯口的經歷,只怕風吹霜侵冷,我便故技重施,裝作不認識。兩位青年不時用眼角餘光掃我,投擲一瞥於“一瞬一瞬的飛翔”,卻終於忍不住,附耳中年漢子:“是他嗎,老師?”後者回答:“是他,別說話。”他們都輕聲細氣,也氣充志定,我因心中有鬼,畏影避跡,結果居然一字不漏都聽到了,顧不得慚愧,只是愈發低頭看書。不知多久,待得抬頭,對面早已無人。

5

黃昏將近,想到還有三十多公里的路程,便結賬拎書出門,先在附近超市採買蔬食,然後趕在天黑前驅車回鄉。來回要花油錢和過路費,不能白來一趟。果然到家天快黑了,放下書,直起腰,對花無語,索性出門散步。晴日不多,也許明朝又是一天風雨。說來也巧,正是工人下班時分,幾十位裝修工人熙攘往前,我也混同其中,信步闌珊。不知多少時日未曾打理,鬍子拉碴,黃昏時分踽踽獨行,自我感覺跡近滄桑,頗有儀式感。靠近小區門口這塊長方形地段新起來幾棟住宅樓,不少人家正在裝修。其中一個門洞前停了一輛大貨,看得出來是剛剛卸載完畢。貨車旁居然有十來個青年男女,有幾個還身背雙肩跨,包帶上斜係著個棉織小動物。我這個一生站講台的教書匠,一眼就看出來他們是學生也。看他們唧唧喳喳,看他們攘袂引領,看他們金其聲而玉其振,我頓時犯了花癡,邁不開步,並且不知羞恥地居然淚眼婆娑了。裝修工人已然走遠了,我卻停在近處看著他們說說笑笑,鬧鬧哄哄。話語嘈雜,概分好幾堆,熱氣騰騰,山呼海嘯。但飄來的聲音裡有“畢業答辯,有驚無險”、“那個馬院的老師老是盯著女生看……”、“某某教授是行政法專業的,跑來我們民法這邊答辯,濫竽充數呀”、“本來想寫違憲審查,後來導師不同意,說這都什麼時候了,你還癡心妄想寫這個題目,你敢寫,我還不敢指導呢……”,以及“咳,他居然要我回答究竟黨規是不是國法這個問題,那我怎麼著也只好說不是國法勝似國法呀”——諸如此類,不一而足,乖乖隆地咚,這才明白他們居然是我這個被逐出校園的無業老人的同行呢。

說時遲那時快,路燈忽地都亮了,偏是這個門洞口燈桿上一枝獨黯。樓里走出來一位中年男子,鼻樑上架著無框眼鏡,瘦瘦條條的骨架上是短袖衫長褲子,一出門徑直毫不忌諱地將我打量一番,然後示意小年輕們圍攏身邊,壓低嗓音,但清清楚楚。“同學們注意點兒,這裡是遠郊,各種人雜得很,不認識的來搭訕不要理。大家到齊了,一起去吃飯。”話音甫落,便有兩三位學生轉身掉頭,三步兩步,到我身邊,和顏悅色:“師傅,天黑了,累了一天,快回家吃飯歇息吧,我們在幫老師搬家,沒什麼好看的呀。”話音既落,這被喚作師傅的老人如夢方醒,花癡頓消,急忙諾諾,猥瑣而去,聽得背後有人嘀咕:“哎呀,不懂禮貌,真的,他老盯著看什麼看呀!”

曾幾何時,因為明星、網紅與算命的,三教九流,都叫老師,更加上老師裡頭真有不少不配稱為老師,我羞於為伍,半真半假,且莊且諧,便讓學生改叫我師傅。他們也叫得朗朗上口,“許師傅”長的,“許師傅”短的,還說莊士敦與翁同龢不也叫師傅嘛,云云。至於主要流行於校園工科學子口中的“老闆”一詞,仿佛脫胎於英文的boss,初或意在調侃與模仿,而英漢轉換之際,意味多有差池,尤其是在權錢愈益主導學術的這個時段,故而,吾師門雅不欲也。不意今日真成師傅了,可見詩人所詠,“時間啊,令人困惑的魔道”,何其深邃,非九死一生,難得此佳句。學生童言無忌,歡喜還來不及呢。可我對這個兩條瘦腿在褲管裡晃蕩的中年男子真的頗為不屑。你要是端這一行飯碗,連老子是誰都不認識,你他娘的還研究個什麼法學,在法學食槽裡混個什麼混呢?!

好混著呢,抑或,才混得好呀!

哈,章潤這娃,自負不凡,自作多情,自作自受,自得其樂,喲,喲嚯,喲嚯喲,一片片油菜花花滿山山的開,妹妹的那個心思,啊呀呀呆,哥哥你自己猜……

6

天夜了,不時傳來遠處的蛙鳴。天又陰了,估計明早還要下雨。一隻蚊子蓄謀已久,花樣盤旋,近身俯衝,看準了我的血脈,我以上下揮手表達厭煩,而以左右橫掃做決絕狀自衛。鏖戰幾個回合,不分勝負,乾脆拉倒,任隨它下口,就算餵它幾滴,不枉小生靈今夜陪我的深情厚義。畢竟,“臨鸞鏡,粉容相併,試問誰端正?”燈下枯坐,突然想起前不久超市停車場碰到一位熟人,蒙他停下來站著閒聊了幾句,還告訴我說,幾天前大家酒聚,海闊天空,逸興遄飛,“某某老師還問起過你呢!”便耐不住寂寞,摸出電話,打過去試試看。果然還是這個號碼,這讓我有點兒興奮莫名,仿佛一種類似於天行有常的感覺悄然注入心田。老師聲音依舊,略有些耳背,因而我扯著嗓子大聲嚷嚷,惹得小蚊帶著幾個同夥,在我頭顱另一側的耳輪上下翩躚跟著嚷嚷。寒暄幾句後,老師直入正題,語氣有點兒變化:“你的事我聽說了。哪裡跌倒哪裡爬起來。聽說你走路都要拄拐杖了呀,我這麼大年紀了,還不用呢。混成這樣原因在自己。錯誤是很嚴重的。犯什麼錯誤都不能犯政治錯誤。正視自己的錯誤,認識到錯在哪裡,不要再犯。我身體不好,今後不要打電話來。”啪,掛了。

放下電話,回想一九八三年,整整三十八年前,那個北國秋意爛漫時節,我二十郎當,身無分文,懵懂怔忡,從山城蹩來京城,入讀研究生院。第二年老師給我上過兩周課,大稿紙攤在桌上,手按著,一行一行,照本宣科。他念得全心全意,我們聽得三心二意,但雙方好像都誠心實意。記得他是畢業後留校任教的。“文革”中學校解散,好像分配到某地公安部門工作。一九八零年代初重新“歸隊”回校任教,這便有了我們這師生緣分。我畢業後也留校任教,同在一系,師生又成了同事。後來他的幾篇文章,長長短短,“青年教師”的我受命代筆,“鍛煉,鍛煉”,他也欣然納受。

7

走筆至此,我要坦白,上文所述是一天裡發生的事,其實是分別散落在這個夏季前前後後的幾天裡。我把它們攏合一體,裝模作樣,疏影橫斜,是要增加幾分“敘事的戲劇性”。

朋友,人生如戲嘛!

8

波蘭詩人,也是諾獎得主的切斯瓦夫·米沃什老爺子寫過兩首詩,題為“皮爾遜學院”和“薩拉熱窩”,摘引如下:

質量在世紀末變成數量,

而地上的生活已經不同以往。

虛無,正如先知們一再重複,只能誕生新的虛無,他們再一次像那些運往屠宰場的牲畜。

……

他們在準備這一切,同時自我保證:“至少我們是安全的”……

是啊,九泉之下的米爺啊,你說得對,他們都覺得,“至少我們還是安全的”。也許,並祝福,他們真的是安全的。

辛丑七月初稿,有小蚊數只相伴。

九月廿七,耶誕二零二一年十一月一日,落葉時分,定稿於故河道旁。